Police arrive en masse to enforce an illegal eviction of an Indigenous community in Paraguay. Ka'a Poty community member via Al Jazeera

A wave of violent conflict is sweeping the Paraguayan

countryside, driven by demand for land to grow a single crop: soy.

Nestled between Brazil and Argentina in the heart of South

America, Paraguay is the world’s fourth largest exporter of soy. But the social

and environmental impacts of its soy industry have received little scrutiny

compared to its giant neighbours.

This is partly because soy production in Paraguay generates

less deforestation. Soy is grown principally in the country’s fertile east,

which had already lost the bulk of its forest by the dawn of the twenty-first

century.

As our investigation reveals, however, this fact has

emboldened western corporations to turn a blind eye to widespread human rights

abuses. In Paraguay’s soybean heartlands, rural communities are enduring illegal

evictions, armed attacks, poisoning by illegal fumigations, and criminalisation

– all to secure land to grow soy for export.

In 2022, Global Witness travelled to eastern Paraguay to

investigate this conflict.

Campesino and Indigenous peoples at the 'XXVII Gran Marcha Campesina' (27th Big Campesino March) demonstrate against land injustice and impunity, Asuncion, 25 March 2022. Global Witness

We visited a range of Indigenous and campesino communities across

four of Paraguay’s main soy-growing departments, gathering evidence of the

abuses and identifying the soy producers responsible.

We saw how abandonment by the Paraguayan state is leaving

communities defenceless in the face of the aggressive expansion of large-scale

agribusiness. We witnessed how communities of land and environmental defenders

are engaging in resistance. And we documented how complaints of human rights

violations are linked to some of the world’s biggest companies.

90%

of Paraguay’s soy harvest is exported. These exports are handled by

massive multinational commodity traders, which control the global trade

in grains and

oilseeds. Around 40% of Paraguay’s soy exports are handled by just two

of these

firms: Cargill and ADM. Together, these US giants dominate the

Paraguayan

economy, extracting huge revenue from Paraguayan land.

For each of the community conflicts, we identified the traders

buying from the soy producers causing human rights abuses. In every instance,

we found links to either ADM or Cargill. In two cases, we also uncovered ties

to a third US giant, named Bunge.

We then traced the onward journey of this soy. 80% of the global

soy harvest is used in animal feed. Drawing on shipping data and interviews

with industry insiders, we mapped the opaque supply chains connecting rights violations

in Paraguay to two of Europe’s biggest meat companies.

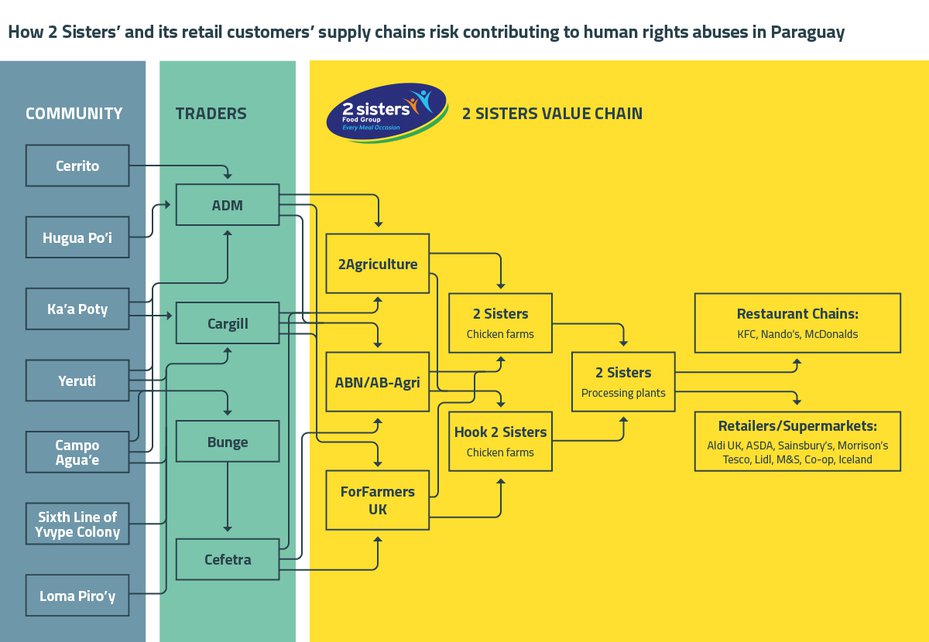

One route led us to 2 Sisters, the UK’s biggest chicken company

and a supplier of corporate giants including Tesco, Marks and Spencer, KFC and

Nando’s.

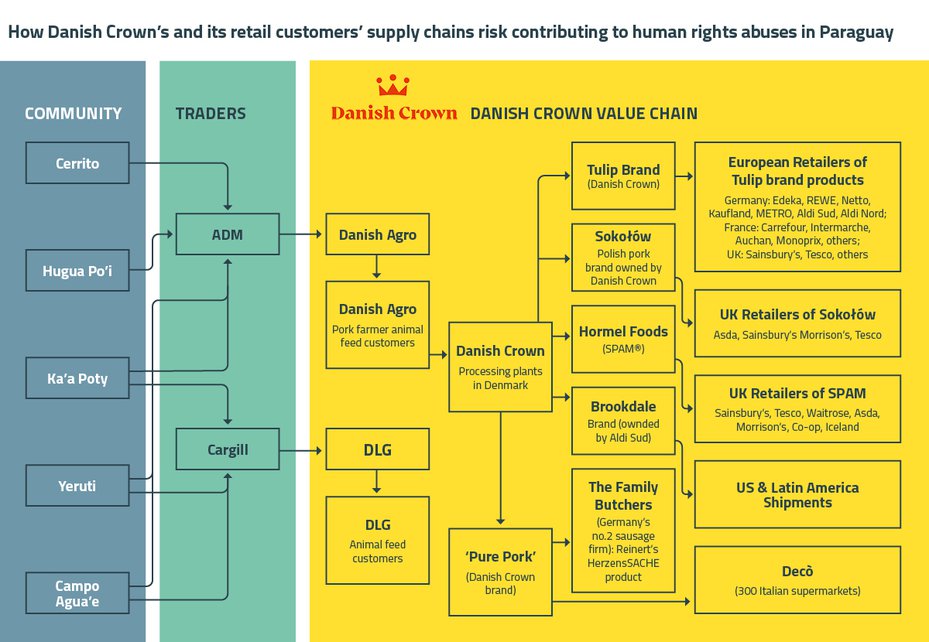

The second led us to Danish Crown, Europe’s largest meat

processing company, which supplies a rollcall of the continent’s biggest

retailers, including Sainsbury’s, Carrefour, Intermarché, Lidl, and Netto.

The traders’ historical and ongoing

purchases of soy from Paraguayan farmers who have violated basic human rights

represent egregious failings under international UN and OECD standards.

Moreover, these failings are all too readily inherited by the

European corporates our investigation encountered – even being baked into

voluntary sustainability commitments they have adopted to ensure soy in their

value chains is ‘responsibly produced’ by 2025.

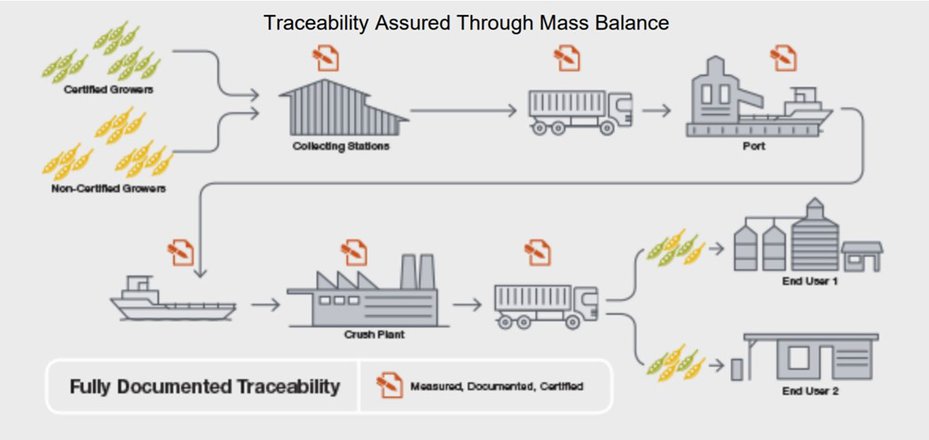

Our research reveals how the companies involved have adopted what

we consider to be an accounting trick known as ‘mass balance certification’.

This system – ostensibly intended to help clean up Europe’s soy imports – mixes

soy from farms like those we visited in Paraguay into nominally certified

consignments, resulting in the tainting of most of Europe’s Paraguayan soy

imports.

From the traders themselves, through the animal feed companies

they supply, and onto the mega farms, meat processors, and big brand retailers

named in this report, the acceptance and promotion of this nominally

‘sustainable’ soy constitutes negligence dressed as sustainability, and locks

human rights risk into these supply chains.

As a result of these failings, our investigation shows millions

of European consumers of 2 Sisters’ and Danish Crown’s products are also likely

purchasing products made at the expense of the fundamental human rights of

Indigenous and campesino communities in Paraguay.

We

sent our findings to all the companies concerned. Nearly all of those who

responded said they would investigate what they regarded to be violations of

their policies on human rights and land rights. All of the responses received

are summarised in a table

below and some are included in this

report.

European governments have long

committed to end corporate complicity in human rights and environmental harms.

The European Union (EU) has recently

proposed two laws mandating that companies eliminate human rights,

environmental and climate abuses from their value chains.

The proposed Deforestation Regulation,

and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) will both

require companies to carry out checks on their supply chains – known as due

diligence – to identify their existing and potential impacts, prevent their

activities from contributing to further harms, and address those that have

already occurred.

This process has the potential to help

eradicate abuses from corporate value chains, particularly for high-risk

agricultural commodities such as soy.

Yet these proposals are still under negotiation, and it is critical to ensure they provide sufficient accountability.

Industry

lobbying by many of the traders and animal feed companies exposed in

this investigation has advocated for the new rules on deforestation to

accept leaky certification systems that would ensure continued imports

of soy tarred by land grabbing and human rights harms. Although the

European Parliament is working to resist this, the proposed EU

Deforestation Regulation will only apply to human rights cases linked to

recent deforestation, and cases like those in this report will not be

covered.

The proposed draft EU directive on human rights due

diligence is also full of loopholes. Companies like ADM and Cargill may

not be required to do due diligence on all the farmers they source from,

such as those in Paraguay our investigation exposes.

The draft directive also formalises a role for exactly the types of ‘industry initiatives’ and ‘third-party verifications’ our investigation reveals are a conduit for structural human rights risks, and can prevent companies from being held legally accountable.

The draft EU

directive on human rights due diligence must support and in no way replace or

undermine existing rights under the ILO Convention 169 and UN Declaration on the

Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), including rights of Indigenous

Peoples not to be removed from their lands or territories, their right to

redress or compensation for land rights violations, and their right to exercise

free and prior informed consent (FPIC).

The UK

government has also been urged to introduce similar human rights and

environmental due diligence legislation for businesses, but has yet to propose

concrete plans to do so. Separately, some of the cases in this report could

potentially be addressed under Schedule 17 of the Environment Act 2021. Yet

Schedule 17 requires further regulations to be made by the Secretary of

State before it can bring

accountability to companies such as those in this report. The

timetable for the passage of those regulations remains uncertain.

Our investigation highlights why European lawmakers must ensure they strengthen proposed legislation to prioritise people and planet over accounting tricks, opacity, and impunity for the companies dominating Europe’s industrial food system.

They must impose strong, enforceable rules holding companies

accountable for the elimination of human rights and environmental harms from

their supply chains and the provision of remedy where harms occur.

The Indigenous and marginalised farming communities impacted

by human rights violations in rural Paraguay are counting on it.

Problems in Paraguay

- Soy

production in Paraguay is fuelling a wave of conflict and dispossession,

impacting both the country’s Indigenous peoples and its small-scale farming or

campesino communities

- In

2022, Global Witness visited a range of the communities affected, travelling

through four of Paraguay’s major soy-producing departments: Alto Paraná;

Candindeyú; San Pedro; and Caaguazú

- On

this journey, we documented a raft of serious human rights abuses: forced

evictions; armed attacks; chemical poisoning; threats; intimidation, and the

criminalisation of communities pursuing legitimate land claims

Locations in Eastern Paraguay of Indigenous and campesino communities impacted by human rights and land rights harms linked to soy production, and the facilities of companies involved in commercialising the soy produced.

The Cerrito community

The Indigenous community of Cerrito is situated among the

endless soy fields that blanket Alto Paraná, Paraguay’s biggest soy-producing

region. Its residents – members of the Ava Guarani people native to eastern

Paraguay – are battling to return to land which once belonged to their

ancestors, but today is dominated by industrial agribusiness.

“When I was 12 or 13, this was all forest, with many

fruits,” recalls Arnalda Martinez, a woman in her sixties who grew up, like her

parents and grandparents, in the area claimed by the Cerrito community. “We

hunted in the forest, we fished in the forest, we extracted honey and medicinal

plants. And now what has happened? The forest is gone. There’s only soy,

nothing else is left.”

ELDERS OF THE AVA GUARANI COMMUNITY OF CERRITO PREPARE FOR A CEREMONY, 29 MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS

ARNALDA MARTÍNEZ, MEMBER OF THE CERRITO INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY, SPEAKING TO GLOBAL WITNESS, 29 MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS

A CEREMONIAL DANCE IN THE JEROKY (TEMPLE) OF THE CERRITO COMMUNITY, 29 MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS

WOMEN OF THE CERRITO COMMUNITY TAKING PART IN A CEREMONIAL DANCE, 29 MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS

This transformation began one morning in 1955, when a young army captain was handed a historic mission: to open a route through the dense

forest that cloaked the south-east of Paraguay.

The project launched a wave of colonisation nicknamed “the march to the east”,

which saw the area, inhabited by a rich patchwork of Indigenous peoples, pass

into the hands of private landowners.

“Indigenous people found themselves cornered in the most

remote areas of large properties,” explains anthropologist Gloria Scappini.

“They opted first for flight and refuge, and then for migration.”

Thousands died, and Alfredo Stroessner, Paraguay’s brutal Cold War dictator,

was accused of genocide.

In 1992, following Stroessner’s ouster, Paraguay adopted a

progressive new constitution. Article 64 affords Indigenous people wide-ranging

new rights, prohibiting “the removal of Indigenous people from their habitat

without their express consent.”

It’s on the back of such rights that Indigenous communities such as Cerrito are

fighting to return to their former territory.

“We won’t let anyone take away our culture,” says

Martinez, sitting in front of Cerrito’s wood-walled Jeroky or temple. “So we organised among

ourselves to return to where they had expelled us. We returned to recover the

forest for our children.”

ARNALDA MARTÍNEZ IN FRONT OF THE HOME OF HER DAUGHTER, WHICH WAS DESTROYED DURING AN EVICTION. COMMUNITY MEMBERS WERE NOT GIVEN TIME TO COLLECT THEIR POSSESSIONS OR CLOTHES. GLOBAL WITNESS

The Cerrito community returned to land now held by a

powerful local soy producer, German Hutz, who possesses

titles to tens of thousands of hectares across the

departments of Alto Paraná and neighbouring Itapua. In 2020 Hutz was involved in an injunction

to retain his possession of land claimed by the community.

Shortly afterwards, in March 2021, court officials cited this case in

requesting police assistance to evict the Cerrito community.

Police have since evicted the community three times: firing

guns and teargas canisters to drive out the residents, and then incinerating their homes and temple,

destroying their crops, and killing their animals.

Following the third eviction, in May 2022, community members were left homeless

in Paraguay’s cold winter, some of the children without clothes, as they were

given no time to gather possessions.

Paraguay’s state Indigenous Institute (INDI) condemned

the evictions, highlighting a range of institutions, including themselves, who should have been consulted before any measures were taken. Senators in

the Paraguayan Congress questioned the proceedings that authorised the evictions. Rights

groups point to a raft of irregularities, most glaringly, that all three

evictions were authorised not by a judge but by a public prosecutor, deprivingthe community of any opportunity to have its land claim heard. As a result,

the evictions were illegal and can be considered “forced evictions”: described

by the UN as “gross violations of a range of internationally recognised human

rights.”

Soy harvested from the area claimed by Cerrito is trucked to

a large silo owned by German Hutz,

located in the nearby settlement of San Lorenzo. Local industry sources

indicated ADM may source soy from the silo,

which ADM did not deny when put to them. Hutz did not respond to any of the

allegations when contacted by Global Witness.

A little south of Cerrito, in 2021

another Ava Guaraní community,

named Ka’a Poty, also suffered

two forced evictions, the destruction of dozens

of homes and its government-recognised school,

despite possessing title to more than 1,000 hectares

and a

court ruling affirming its tenure. The community lived homeless in Asuncion for

eight months after the second eviction, in November 2021, but following

further verification of their title by state agencies

were

returned to their land by the government in June 2022.

Nonetheless, tensions with farmers remained high,

and in August 2022, some community members attacked a farm on the community’s

land, allegedly threatening, beating and

attacking the inhabitants,

and now

face a raft of charges.

A GATE INSTALLED BY A SOY PRODUCER BLOCKS ACCESS TO LAND TITLED TO THE KA’A POTY COMMUNITY. GLOBAL WITNESS

Soy producers

operating within the Ka’a Poty’s claim include Agricola Entre Rios and Agro Integracion.

Both Cargill and ADM source from Agricola Entre Rios, including via a local

intermediary named COPRANAR. Cargill also buys soy from Agro Integracion. Agricola Entre Rios did not respond to the allegations we put to

them, and despite extensive efforts we were unable to contact Agro Integracion.

Neither ADM nor Cargill denied sourcing from Agricola

Entre Rios or Agro Integracion, or any specific soy producer our research

identified as their suppliers. Both US firms indicated they had initiated investigations into the

violations of their policies uncovered by our research. On 13 September,

two weeks after receiving information from Global Witness, ADM said a record of

its investigation into community cases in this report would be available in its

public grievance log ‘in the next few days’. No such record had been published

at the time of writing.

On 19 September, ADM claimed that its preliminary

investigation had found that “none of the properties/farms (polygons) belonging

to suppliers that source for ADM overlap, or encroach in any way, with either

Indigenous Territories or community settlements of smallholders. None of the

farms from where ADM sources soy suffered evictions.” However, it did not

explain how this could be the case in relation to Cerrito or Ka’a Poty

communities. Nor did ADM indicate it had consulted with relevant communities.

ADM’s grievance protocols require the company to engage with relevant

stakeholders and publish a record of issues on its public grievance log within

two weeks of receipt of information about policy violations.

How soy conquered eastern Paraguay

Most of this expansion occurred in the country’s lush

subtropical east, displacing the great Atlantic Forest which spilled into

Paraguay from Brazil’s Atlantic Coast. Between 1973 and 2000, two-thirds

of Paraguay’s Atlantic Forest vanished - a loss of 40,000 square kilometres, an

area around the size of Switzerland.Now, what remains of this forest is protected by a zero-deforestation law.

But while soy production today drives less deforestation in Paraguay than in neighbouring Brazil,

it is fuelling a wave of conflict and dispossession that has gone unnoticed

outside the small South American nation.

“We hunted in the forest, we fished in the forest, we extracted honey and medicinal plants. And now what has happened? The forest is gone. There’s only soy, nothing else is left.”

Arnalda Martínez, member of the Cerrito Indigenous community

The stories of Cerrito and Ka’a Poty reveal only a fraction

of this crisis. In just one year, between 2020 and 2021, rights groups

documented twelve forced evictions of Indigenous communities, affecting 725

Indigenous families. They also registered a further ten violent attempts to

force small-scale farming or campesino communities off their land.

Nearly all these conflicts were related to soy production to

meet overseas demand. 90% of Paraguay’s soy harvest is exported.

Around 40% of these exports are handled by either ADM or Cargill. The European Union (EU) is the single biggest destination for Paraguayan soy, while the UK is fourth:

potentially implicating millions of consumers across Europe in human rights

abuses against Paraguay’s Indigenous and campesino communities.

A SOY SILO OWNED BY BUNGE IN EASTERN PARAGUAY. GLOBAL WITNESS

The Yerutí colony

Ruben Portillo was just 26 years old when he noticed painful sores on his face and

fingers. At first he ignored them, continuing to work on his family

farm in the village of Yerutí, planting beans and watermelons in the sweltering

Paraguayan summer. But a few weeks later, he developed a high fever, nausea and

diarrhoea. Before long, he didn't have the strength to stand up.

His sister, Norma, hired a pick-up truck to take him to

the nearest hospital. But it was too late: he died on the way.

Over the next few days, 22 other Yerutí residents were

admitted to the same hospital, including Ruben’s two-year-old son Diego. The

influx alarmed the hospital’s director. Noting that it was January, a month

when intense fumigations precede Paraguay’s soy harvest, she contacted the

Environment Ministry to voice her concerns.

A week later, government inspectors travelled to Yerutí.

They documented a catalogue of egregious violations of Paraguay’s environmental

law: large soy extensions bordering family farms with no buffer zone separating

the two; soy seeded to the verge of community footpaths, with no protective

strip of vegetation shielding residents. Tests found endosulfan, aldrin and lindane, all either banned or restricted in Paraguay, in the well water from which the Portillo family drank.

HERMENEGILDA CÁCERES, MOTHER OF RUBÉEN PORTILLO, MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS

ISABEL BORDON, PARTNER OF RUBÉEN PORTILLO, A YERUTI RESIDENT WHO DIED OF PESTICIDE POISONING FOLLOWING ILLEGAL FUMIGATIONS OF SOY PRODUCERS SUPPLYING MAJOR INTERNATIONAL TRADERS. GLOBAL WITNESS

NORMA PORTILLO, SISTER OF RUBEN PORTILLO, IN YERUTI, MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS

The inspectors also flagged flagrant negligence on the

part of two companies, Hermanos Galhera and Condor Agricola,

cultivating soy near the homes of the victims. “The bad management of

chemical containers, scattered over the ground,” was causing chemical residues

to seep into water sources, they observed.

Both firms washed their spraying equipment in streams used by the community,

and neither had an environmental permit authorising their operations.

“Neither of the two met the most basic standards of environmental control,” one of the inspectors told a local Catholic radio station.

On the back of these findings, both firms were issued

administrative fines. But they appealed the decision and, shortly afterwards,

the cases against them were dropped.

Norma, however, refused to abandon the fight for justice.

Giving up on the Paraguayan justice system, she took her brother’s case to the

United Nations (UN). Six years later, the UN Human Rights Committee

issued a damming resolution, concluding that the Paraguayan government's

inadequate response to the illegal soy fumigations violated a series of

fundamental human rights, including the right to life, the right to home and

family, and the right to remedy from harm. “More than eight years after

the events reported, the investigations have made no progress," the

resolution finds, emphasising the state’s failure to conduct an autopsy on

Ruben’s body, “even though one was requested on four different

occasions”, or to publish the results of any blood or urine tests performed on

the victims.

Accordingly, the UN ordered the Paraguayan government to

“undertake an effective and thorough investigation into fumigations with

agrochemicals”

and “impose criminal and administrative penalties on all the parties

responsible.”

In particular, the resolution highlights the role of the companies Hermanos

Galhera and Condor Agricola.

Three years since the resolution was issued, however, no one has been penalised for Ruben’s death.

Meanwhile, the situation in Yerutí continues to deteriorate. When Norma first

brought her case to the UN, soy fields hadn’t reached her lot, she says. Now,

monocrop production runs right up to her fence, scorching the pasture for her

small herd of cows and blighting the crops in her vegetable garden. “They’re

fifty metres from my house without any barrier,” she laments.

The inexorable advance of soy monoculture has eroded the

entire community, residents say. Yerutí was founded amid the optimism of the

initial post-Stroessner years, on land that a former Minister of Education had

returned to the state as compensation for embezzling public funds. Then, it had

223 lots, each busy with activity. Now, just over 30 remain. In

2021, authorities closed the village’s

school, citing a shortage of

students. Diego,

who survived the poisoning which killed his dad and is now a teenager, must

travel 20 kilometres every day just to attend classes. With no public

transport, he drives there on a motorcycle.

Global Witness found Hermanos Galhera continuing to

operate just a few kilometres from Yerutí, harvesting soy and delivering it to

ADM, which owns a silo 10km from Yeruti. Hermanos Galhera also supplies soy to

Cargill and Bunge, according to soy industry insiders. Condor Agricola also

continues to operate in the local area and likely

supplies soy to ADM.

Neither Hermanos Galhera nor Condor Agricola responded to the allegations we

put to them.

ADM’S SILO AT CURUGUATY, CANINDEYÚ, SUPPLIED BY HERMANOS GALHERA, A SOY PRODUCER NAMED IN A UN RESOLUTION AS HAVING ILLEGALLY FUMIGATED SOY CROPS NEIGHBOURING YERUTI COLONY. GLOBAL WITNESS

The Campo Agua’e community

Two years after condemning state failures in Yerutí, the UN

issued another ruling denouncing the devastating impact of fumigations on a

nearby Indigenous community.

Campo Agua’e is the fruit of a

decades-long struggle by Ava Guaraní leaders to safeguard a piece of their

ancestral territory. Settled in the 1960s, as Stroessner’s March to the East

was gathering pace, the community today consists of 980 hectares that were

expropriated from a local agribusiness. For the Ava elders who fought for the

land – now buried in a cemetery on a nearby hillside – it ensured a space for

their descendants to maintain their culture.

But it’s this very culture that is threatened by unchecked

and illegal fumigations. The

destruction of local biodiversity is eroding “traditional knowledge associated

with Guaraní cultural practices of hunting, fishing, gathering and

agroecology,” the UN finds, citing community concerns that “fruit trees have ceased producing

fruit” and “wild beehives disappeared due to the mass mortality of bees.”

Elements essential to Ava dance and ritual – such as wax for ceremonial

candles, or a specific variety of maize needed to make a fermented drink named

chicha – have vanished, community members report, while ceremonial baptisms have ceased taking

place, as the necessary materials are no longer obtainable.

The

loss of such ceremonies denies children the rites crucial to strengthening

their cultural identity,” the UN resolution warns.

CHILDREN PLAY IN FRONT OF THE SCHOOL AT CAMPO AGUA’E, WHERE EDUCATION HAS BEEN SEVERELY IMPACTED BY ILLEGAL PESTICIDE FUMIGATIONS BY SOY FARMERS SUPPLYING ADM, BUNGE, AND CARGILL. CREDIT: GLOBAL WITNESS

CHILDREN PLAY AT CAMPO AGUA’E, AN AVA GUARANÍ COMMUNITY IMPACTED BY ILLEGAL SOY FUMIGATIONS IN CANINDEYÚ DEPARTMENT, PARAGUAY. GLOBAL WITNESS

AVA GUARANÍ BOYS PLAY FOOTBALL AT CAMPO AGUA’E. GLOBAL WITNESS

LUCIO SOSA, A TEACHER IN THE CAMPO AGUA’E COMMUNITY, WHO SPEARHEADED APPEALS TO THE UNITED NATIONS FOLLOWING THE PARAGUAYAN STATE’S FAILURE TO PROTECT THE SETTLEMENT FROM ILLEGAL SOY FUMIGATIONS. GLOBAL WITNESS

ROSANA RIVEROS, A VICTIM OF PESTICIDE POISONING IN CAMPO AGUA’E, 7 MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS.

Indeed, the fumigations have had particularly severe impacts

on the community’s schoolchildren. A 2009 government inspection discovered

spraying just ten metres from the school while children were in class, an

egregious violation of Paraguayan law, which stipulates a

minimum distance of 100 metres. It also discovered unregistered agrochemicals on the property of one of the two

firms responsible for the illegal fumigations, Issos Greenfield, and concluded

that they “

systematically failed to comply with environmental regulations."

“We got ill, we had terrible headaches, we had

diarrhoea, coughs, fever,” says Rosana Riveros, a young woman now in her early

twenties who studied in the community’s school. “It was very difficult to concentrate, we couldn’t learn what we needed

to.”

An investigation was opened into these violations, but,

mirroring the experience of Norma in Yerutí, it was soon dropped without anyone

being prosecuted. “More than 12 years after

the victims filed their criminal complaint regarding the fumigation with toxic

agrochemicals, to which they have continued to be exposed throughout this

period, the investigations have not progressed in any meaningful way and the

State party has not justified the delay,” the UN observed in October 2021.

“It’s all written in

the law, but who’s going to enforce it if not them?” asks Lucio Sosa, Riveros’

teacher, who has spearheaded the community’s battle against soy production.

While operating next to Campo Agua’e, Issos Greenfield

received financing from ADM and sold soy produced on the land to the US firm.

Issos Greenfield ceased working in the area a few years ago; now, a Paraguayan

firm named Somax SA operates there.

While Somax is not responsible for the violations committed by Issos, both the UN

and community residents state that fumigations continue to seriously impact the

community. Sosa reports that Somax has installed the required protective

barriers in some places, but not others. Community leader Benito Oliviera, who

worked with Lucio on the appeal to the UN, is more emphatic: “the situation has

not improved at all. It’s getting worse and worse as the days go by.”

Somax has sold soy from the land to ADM, Cargill and Bunge,

all of whom have silos within ten kilometres of Campo Agua’e.

ADM did not deny sourcing from either Hermanos Galhera or

Condor Agricola. Nor did it deny sourcing soy from Issos Greenfield or Somax

SA, or having financed Issos Greenfield after the Paraguayan government had

accused the firm of conducting illegal fumigations. Neither Cargill nor Bunge denied sourcing

from Somax SA. All three US companies said they had initiated

investigations into the violations of their policies uncovered by our research.

CAMPO AGUA’E IS SURROUNDED BY EXTENSIVE SOY PLANTINGS, THE ILLEGAL FUMIGATION OF WHICH HAS SEVERELY IMPACTED THE COMMUNITY. GLOBAL WITNESS

A land soaked in pesticides

The expansion of Paraguay’s soy industry has paralleled a

massive increase in the country’s use of agrochemicals. Imports of these

products – principally the pesticides glysophate, 2.4D and paraquat

– grew almost sixfold between 2009 and 2017, increasing from 8,800 to 52,000

tonnes. One study estimated that, in 2017, Paraguay – home to 0.09% of the

global population – imported more than six per cent of all the agrochemicals

sold in the world: 7.4 kilograms of agrochemicals per inhabitant.

Paraguayan law mandates a buffer zone of at least 100 metres

between fumigations and human settlements, including schools and health

centres.

This is already weak compared to similar jurisdictions: neighbouring Argentina

requires a buffer zone of at least 500 metres.

But, in Paraguay, as the experiences of the two communities above demonstrate,

even the rules that do exist are rarely enforced.

Nor are Yeruti and Campo Agua’e isolated cases. In October

2022, the UN Rapporteur for toxic substances and human rights issued a damning

assessment of the situation in Paraguay. Ordering the government to comply with

the Yeruti and Campo Agua’e rulings, he concluded that “laws on pesticide use

aren’t enforced” and that this “generates impunity before violations of the

human rights of thousands of people exposed to toxic contamination.”

During a visit to the country, he found many Indigenous and

campesino communities surrounded by vast monocrop plantations. "Those who

oppose the contamination of their communities are frequently criminalised by

the Public Ministry,” he observed.

AVA GUARANI CHILDREN OBSERVE PESTICIDE SPRAYING AT THE EDGE OF THEIR VILLAGE, CAMPO AGUA'E. © NEIL GIARDINO / @NEILGIARDINO

Another recent

study highlighted the impact on schoolchildren. Published in 2020, it identified 51 schools within 100

metres of extensive monocrop plantations,

putting the health of almost 4,000 pupils at risk.

In some instances, researchers discovered that schools were closing for days at a time when

fumigations were at their most intense.

One seriously impacted district is Minga Pora, in Alto

Paraná- the same district in which the Cerrito community is fighting to return

to its ancestral land. Nearly a third of Minga Pora’s schools

– eight out of 25 – are within 100 metres of intensive fumigations, the study

found.

As in other districts visited by the researchers, community members said they’d

complained to the local authorities, but reported that no action had been taken.

The state is complicit to the degree that people have stopped bothering to denounce violations, and instead resort to negotiating directly with the soy farmers.

The Sixth Line of Yvype colony

Aida Gonzalez knew that when she

and her neighbours decided to fight for a piece of land that had been usurped

by soy producers, she would be taking on powerful interests. Five

years later, she has endured a series of violent evictions, attacks by armed

civilians, and repeated threats of

imprisonment. Now she is facing renewed efforts to jail her and others

for up to ten years, simply for resisting illegal land grabs by agribusiness in Paraguay.

Aida is one of many people from

traditional farming families in Paraguay who lack any access to land. With most

of the country’s fertile land occupied by large-scale agribusiness, hundreds of

thousands of landless farmers live with relatives in overcrowded houses in Paraguay’s

impoverished towns and villages.

Together with neighbours in this

same situation, Aida identified state land in an old small-scale farming or campesino

community which had been irregularly occupied by soy producers. The soy

producers had begun cultivating land after it was abandoned by its original

residents, campesinos who were driven out by intensive

fumigations. “The plantations surrounded me, they were 28 metres from my door,”

says Catalino Silva, one of the few original residents who refused to leave.

Silva blames “fumigations, corruption, state abandonment” for the

disintegration of his hometown, named the Sixth Line of Yvype Colony.

FRANCISCA PORTILLO, RECOUNTED HOW, IN MARCH 2021, POLICE AND ARMED CIVILIANS FORCED FOURTEEN FAMILIES FROM THEIR HOMES AND BURNT THEIR CROPS AND POSSESSIONS. GLOBAL WITNESS

AIDA GONZALEZ HAS SUFFERED YEARS OF CRIMINALISATION AND MULTIPLE EVICTIONS FOR DEFENDING HER RIGHTS TO LAND AND HER HOME IN THE SIXTH LINE OF YVYPE COLONY. GLOBAL WITNESS

CATALINO SILVA, AN ORIGINAL RESIDENT OF SIXTH LINE OF YVYPE COLONY BLAMES “FUMIGATIONS, CORRUPTION, STATE ABANDONMENT” FOR THE DISINTEGRATION OF HIS HOMETOWN. GLOBAL WITNESS

GERARDO LEZCANO, A FARMER, TOLD GLOBAL WITNESS HIS PREGNANT WIFE LOST THEIR BABY DAUGHTER AFTER A LARGE FORCE OF MOUNTED POLICE CHARGED THE COMMUNITY AND THEIR HOME WAS DESTROYED IN A JULY 2021 EVICTION. GLOBAL WITNESS

Hearing of the situation in

Yvype, Aida and her neighbours decided to petition for the abandoned land

to be delivered to them. They made their claim under Paraguay’s agrarian reform

laws, which require that state land should be delivered to

small-scale farmers rather than large-scale agribusiness. And they adopted the traditional tactic of land activism

in Paraguay to force an indifferent state to act: in 2017, they occupied the

land they were claiming.

Just as Aida expected, the

occupation produced a ferocious response from the soy producers. Through the

next four years, they instigated a series of evictions, in which both police

and armed civilians repeatedly

destroyed homes and crops. One producer, Georg Matthies Derksen, countered with a

raft of criminal charges against Aida and others, seeking to prosecute them for

property invasion among other crimes. At one point, Aida and another activist, Ceferino

Peralta Lopéz, spent two weeks in jail.

Then, four years after occupying

the site, Aida’s resilience finally paid off. Decisions over the

adjudication of state land are the prerogative of Paraguay’s State Land

Institute, named INDERT.

Initially, INDERT had ruled in favour of the soy producers, even allocating them land occupied by campesinos. But in 2021, the President of INDERT was dismissed amid

a corruption scandal. His replacement, Gail González Yaluff,

re-evaluated the Sixth Line case. She found “serious irregularities” in the

past administration’s favouring of the soy producers, concluding that – just as

Aida and her commission had argued – their stance was “in total violation of the Agrarian Statute.” Accordingly, Gonzalez revoked several of those rulings

and moved to “suspend all procedures relating to Yvype Colony”.

After four years of struggle, it

finally seemed that their effort was paying off – and that the Sixth Line

community might spring back to life.

But in Paraguay, which languishes in 128th place

in Transparency International’s 'Corruption Perceptions Index',

things are never so simple. Instead of complying with INDERT’s ruling, the soy

farmers intensified their attacks. In March 2021, police and armed civilians

forced fourteen families from their homes and burnt their crops and

possessions.

Four months later, another six families were evicted by a huge force of police,

some mounted on horseback.

“My wife was pregnant and the sight of a hundred police riding towards us

terrified her,” says Gerardo Lezcano, a soft-spoken farmer whose home was

destroyed during the July eviction. “She lost the baby, our daughter that she’d

been carrying for eight months.”

FRANCISCA PORTILLO, OF THE SIXTH LINE OF YVYPE COLONY, OBSERVES HARVESTERS WORKING LAND FROM WHICH SHE WAS EVICTED. GLOBAL WITNESS

Simultaneously, Matthies Derksen, ramped up efforts to

imprison the campesinos. Aida and several other community members face charges

of land invasion, which, following a recent change in the law, can carry a

prison sentence of up to ten years. The accused face a preliminary hearing in November 2022,

based on alleged trespass committed in October 2021 – after INDERT’s resolution

identifying “serious irregularities” in Derksen’s possession of the land.

“For demanding our rights, for

the simple act of asking for access to a piece of land, they see us as

criminals,” Aida says.

Matthies Derksen has also gone

after the new President of INDERT herself. In 2021, he lodged a criminal complaint accusing her of instigating criminality. INDERT responded

with a defiant statement, accusing Matthies Derksen of trying to “intimidate”

the administration in order to “obtain illegal ownership of rural properties

for extensive exploitation.”

“The legal tricks planted by

certain sectors constitute a flagrant attempt to bully this administration,”

the statement reads, ending: “WE WON’T BE INTIMIDATED BY SECTORS MOTIVATED BY

DARK INTERESTS!"

SOY BEING HARVESTED ON LAND FROM WHICH FRANCISCA PORTILLO WAS EVICTED IN 2021. GLOBAL WITNESS

However, while criminal charges hang over Aida and Ceferino,

INDERT is powerless to rule in their favour, as the charges against them

prohibit them being awarded state land. And should Derksen’s campaign to imprison them be successful, they could face

years in Paraguay’s brutal and overcrowded prison system.

Matthies Derksen

belongs to a cooperative named Friesland. He supplies soy both to a silo operated

by the cooperative and reportedly to a second nearby silo owned by a similar

cooperative, named Volendam. All soy delivered to the Friesland silo

is exported by the Russian grain giant Sodrugestvo. ADM and Cargill are the two international

traders with soy infrastructure including silos and ports closest to the

Volendam cooperative.

The soy producer

responsible for evicting Gerardo Lezcano and his family sells soy to a nearby

silo called Seagri, which has a long-established supply relationship with

Cargill.

Neither Matthies

Derksen, Friesland, Volendam, nor Seagri responded to these allegations when we

contacted them. Cargill did not deny it sources from Derksen’s properties via

Volendam, nor other properties within the community’s land claim via Seagri,

saying it had launched investigations into the violations of its policies

uncovered by our research.

Repression and resistance in the Paraguayan countryside

CAMPESINO AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES MARCH AGAINST LAND INJUSTICE AND IMPUNITY, ASUNCION, 28 MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS

Paraguay

has one of the most unequal land distributions of any country in the world. Just

12,000 people own 90 per cent of Paraguayan land; the remaining 10 per cent is

split between more than 280,000 small and medium-sized producers. Beyond that

lies a destitute hinterland of 300,000 small-scale farming families without

access to any land at all. This generates a Gini coefficient of 0.93, far higher than anywhere else, even in the notoriously

unequal region of Latin America.

Multinational

corporations profit directly from this inequality. The UN estimates that only

6% of Paraguay’s agricultural land is available for domestic food production,

whilst 94% is used for export crops. Soy is by far Paraguay’s

single biggest export, and in 2020, 40% of soy exports were handled by either

ADM or Cargill.

Organisations

representing Paraguay’s traditional farming or campesino communities have

fought to resist this takeover. One, the National Federation of Campesinos

(FNC), claims to have won titles to more than 300,000 hectares since the fall

of the dictatorship in 1989. Their strategy involves

direct action: they identify lands that are illegally held by large-scale

producers, and then they stage occupations, demanding that the state recognise

the claim.

This

struggle, however, has come at a cost. At least 128 campesinos and campesinas have been assassinated, and thousands of farmers imprisoned,

since the return to democracy in 1989.

The

FNC’s goals are supported by experts. “It is of vital importance to fully

implement the long over-due Agrarian Reform,” the UN’s Special Rapporteur on

the Right to Food said during a 2016 mission to Paraguay. She

urged the government to “incorporate human rights principles in order to protect

smallholder farmers and their livelihoods.”

But

rather than pursue such measures, the Paraguayan government is intensifying its

repression of campesino activism. In 2021, President Benitez enacted a law

elevating the sentence for “property invasion” – the tool most often used to

criminalise those demanding land restitution – from six to ten years.

At

the same time, the government has slashed the budgets of the very state

institutions responsible for resolving land disputes. Both the Land Institute,

INDERT, and the Indigenous Institute, INDI, have seen their budgets slashed in

recent years. INDERT’s budget has fallen by two-thirds in just six years, from

US$ 43m (300 billion Guaraní) in 2014, to US$ 26.8m in 2019, to US$ 22.6m in

2020, to just US $15.62m (108 billion Guaraní) in 2021.

Similarly,

INDI experienced a 16% budget cut in 2021. Analysis by one Paraguayan rights

group found that the total budget destined for the purchase of land in 2021

would have enabled INDI to acquire just 600 hectares for Paraguay’s Indigenous

communities, a quantity it called “dramatically insufficient.”

Rights

groups in Paraguay draw a parallel between this lack of state capacity and low

taxes on agribusiness, Paraguay’s principal industry. Calculations by one

civil society group, BASE-IS, estimated that exporters of soy, wheat and corn –

which together represent over 10% of Paraguay’s entire GDP– contribute just 1.72% to the country’s total tax income.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLE CAMPING OUTSIDE THE OFFICES OF INDI – PARAGUAY’S INDIGENOUS INSTITUTE (INSTITUTO PARAGUAYANO DEL INDIGENA) IN THE CAPITAL CITY, ASUNCION, IN MARCH 2022. GLOBAL WITNESS

In

the case of the commodity traders, tax figures obtained by Global Witness

indicate they pay only a fraction of the huge income they generate in Paraguay

back in tax. Customs data show that ADM exported US$ 512m of goods in 2020, a year in which the firm

paid US$6.18m in income tax – equivalent to just 1.2%

of the firm’s enormous export revenues. Cargill’s figures tell an even more

extreme story: in 2020, they exported US$ 713m worth of goods, while paying just US$ 1.46m

in income tax – representing barely 0.2% of their enormous export revenue. In its response to Global

Witness, ADM did not dispute these figures, but affirmed that it “has a firm

commitment to comply with all tax regulations in the country,” as proven by its

“audits and periodic reporting obligations.” Cargill did not comment on its tax

affairs.

These

low tax bills are aided by the lack of any soy export tax, in sharp contrast to

Paraguay’s neighbour Argentina, which imposes a levy of 33%. The UN’s Special Rapporteur

urged Paraguay to ”enact a law introducing tariffs on the export of grain,

including soya, which should help to increase tax revenues and, ultimately,

social expenditure.” However, attempts to create

such a tariff have been repeatedly struck down, both by Paraguay’s Congress and, on the one occasion it

successfully passed the legislature, directly by Presidential veto.

The Hugua Po’i community

MBYA GUARANI INDIGENOUS ELDERS MAKE MUSIC FOR A CEREMONIAL DANCE AT HUGUA PO’I. GLOBAL WITNESS

MEMBERS OF THE HUGUA PO’I COMMUNITY PERFORM A DANCE CELEBRATING THEIR CULTURE ON THEIR LAND. GLOBAL WITNESS

HUGUA PO’I COMMUNITY MEMBERS RETURN TO THEIR HOMES AMONGST SOY PLANTATIONS ON THEIR LAND. GLOBAL WITNESS

The residents of Hugua Po’i, an

Indigenous community in eastern Paraguay, had sworn to resist any attempt to

throw them out of their homes. But when the eviction came, the force was

overwhelming: 400 riot police, submachine guns, horses, a helicopter slicing

the air overhead. Armed solely with bows and branches, they had no option but

to abandon their village and step out into the pouring rain.

As police led people away, armed

civilians swept in from the soy fields to the north. Using tractors and chainsaws, these

men, working under the orders of local soy producers, destroyed

the community’s farms and croplands. They tore down their houses and set fire

to their opy, the spiritual temple of the Mbya Guarani, close relations

of the Ava in eastern Paraguay.

The villagers refused to be cowed, and just

three months after the eviction – which occurred on 18 November 2021 – they reoccupied the site. They began again the hard work of

constructing homes, planting crops, and building a new opy, located

close to an ancient burial ground.

But the threat of another eviction shadowed all this effort.

The same land was claimed by a local farming

cooperative named Tres Palmas. Tres Palmas acquired the land from the

Paraguayan state in 1977, with Mbya communities inside it – triggering the conflict that continues in Hugua Po’i today.

Aiming to prevent a second eviction, Paraguay’s Indigenous

Institute (INDI) sought a protective measure for

Hugua Po’i in the courts. Finally, at midday on 12 July 2022, it was granted.

But it came too late: that morning, hundreds of police had again encircled the

community, enforcing an eviction order from a local judge who, rights groups

argue, did not have competency to rule on the case. Hugua Po’i residents watched as their homes and crops

were razed for a second time. Two weeks later, one of Hugua Po’i’s youngest

members, a two-month-old baby named Néstor Villalba Mendoza, died of breathing difficulties.

ARMED POLICE PREPARE TO EVICT THE COMMUNITY AT HUGUA POI IN JULY 2022. CODEHUPY

TRUCKS LEAVING THE SOY SILO OF FARMING COOPERATIVE TRES PALMAS S/A. GLOBAL WITNESS

Tres Palmas operates a silo 5km

from Hugua Po’i, where they store soy harvested from the disputed land. From

there, soy is trucked directly to ADM’s port facilities south of Asuncion, Port

Sara.

Tres Palmas argue that the evictions were authorised through

the civil courts on the basis of a land title that has been in their possession

for the more than fifty years. The Hugua Po’i land claim is not a case of

Indigenous peoples seeking land restitution, they argue, but rather local

politicians weaponizing Indigenous rights to extort money from private

landowners.

The Loma Piro’y community

A SIGN AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE LOMA PIRO’Y COMMUNITY, WHICH HAS BEEN VIOLENTLY ATTACKED BY LOCAL SOY PRODUCERS SIX TIMES. GLOBAL WITNESS

For the Mbya Guaraní, the land

that lies between the Acaray and Monday rivers in eastern Paraguay is known as

“Mbae Vera”: “the land that shines”. Though the forest that once cloaked

the region is largely gone, its glades and forest trails remain woven

through Mbya mythology.

“For us, it’s land that

gives life to all humanity,” says Mario Rivarola, leader of the Organizacion

Nacional de Aborigines Independientes. “Without land there is no life. We come

from earth, and we become part of the earth again.”

Today, instead of trees, the

“Mbae Vera” is carpeted with vast soy monocultures. Mbya leaders warn that this

dispossession threatens the total disintegration of their culture and community

ties. Hugua Po’i represents a determined effort to preserve

their connection with this ancestal land.

Just 12km north of Hugua Po’i,

another Mbya community is fighting to retain this link with their traditional

territory. Named Loma Piro’y, the community has also suffered serious human

rights abuses at the hands of individuals reportedly acting for local soy

producers.

In December 2020, a group of men

armed with shotguns and electric batons marched into Loma Piro’y. Opening fire

over people’s heads, they ordered them to abandon the land or risk being shot. A

report to the Prosecutor’s Office made by two Loma Piro’y residents describes what happened next. “They

beat up some of our neighbours, fracturing people’s arms, and chased us out.”

Then they burnt the community’s houses, church and

school, and robbed their telephones, their food and their animals.

Despite the violence and death

threats, the community clung on. But the police apparently did nothing, and

three months later, Loma Piro’y suffered another assault. This time, nine

residents were seriously injured.

HOMES OF THE MBYA GUARANI COMMUNITY AT LOMA PIRO’Y BEING BURNED DOWN BY SOY FARMERS, MARCH 2021. SUPPLIED BY COMMUNITY MEMBER.

“My cousin was struck by a

machete here,” says Dominga Coronel, the community leader, pointing at the top

of her head. “His brother was cut on his face, and four or five women were hit

on their arms by clubs.” This time, the authorities did take action, and several

local landowners and soy farmers were charged with coercion.

These attacks, too, were driven by a fundamental clash of

worldviews. In both conflicts, the landowners are descendants of uprooted

Mennonite communities who came to Paraguay with little, seeking to sow a life in the fertile soil. In the case of Loma Piro’y, both the

Mennonites and the Mbya Guarani claim possession of land that was left to

Indigenous people by German pastors in the 1980s. Through subsequent decades,

it was gradually taken over by large-scale commercial farmers.

“Our grandfathers lived in this, our ancestral territory,

here they had their opy,” Armado Portillo, a Loma Piro’y resident, told the

local publication Joaju. “This was a forested place, and now there are

no forests, only soy.”

DOMINGA CORONEL, RESIDENT OF LOMA PIRO’Y, IS FIGHTING TO RETAIN THEIR LAND AND PREVENT HER INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY BECOMING DESTITUTE. GLOBAL WITNESS

THE INDIGENOUS MBYA GUARANI LOMA PIRO’Y ARE SURROUNDED BY SOY PLANTATIONS, WHOSE OWNERS HAVE VIOLENTLY ATTACKED THEM SIX TIMES. GLOBAL WITNESS

THE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITY AT LOMA PIRO’Y, IS SURROUNDED BY COMMERCIAL FARMS. GLOBAL WITNESS

ONE OF THE HOMES OF THE INDIGENOUS MBYA GUARANI COMMUNITY AT LOMA PIRO’Y. GLOBAL WITNESS

Soy produced on land claimed by the Loma Piro’y community is

harvested and delivered to a nearby silo owned by a firm called Agro

Panambi.

Cargill has sourced from AgroPanambi, Global Witness’s research

suggests. Agro Panambi did not respond to Global Witness’s request for

comment.

Neither ADM nor Cargill denied sourcing from Tres Palmas and

Agro Panambi respectively. Both US firms said they had initiated investigations

into the allegations of human rights abuses and violations of their policies.

Defending Indigenous Rights in Paraguay: A Risky Business

A HOME IN THE HUGUA PO’I COMMUNITY IS COMPLETELY SURROUNDED BY SOY. GLOBAL WITNESS

The evictions of Hugua Po’i, Ka’a Poty and Cerrito – plus

the dozen more documented by rights groups in 2021 alone – occurred despite the

clear Indigenous land rights enshrined in Paraguayan law.

These national protections are amplified in various international agreements

which Paraguay has ratified, such as Convention 169 of the International Labour

Organisation, and the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous people.

The recent wave of forced evictions is not the first time

the Paraguayan government has been accused of violating Indigenous

rights, however. Since 2005, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has issued three rulings condemning abuses. In

one case, the Court specifically emphasised that the fact land is in private

hands is not sufficient justification to deny a community’s right to territorial restitution.

This failure to uphold

Indigenous land rights reflects a deep rot in the Paraguayan justice system,

defenders argue. Juan Rivarola, a lawyer with the human rights group CODEHUPY,

says that judges and prosecutors are aware that ruling against powerful

agribusiness interests could destroy their careers. “They tell me, ‘I have to

be flexible on this one, or I could be dismissed’,” he says. “This is very

serious because it affects the independence of the judiciary.”

LAWYERS AFFILIATED WITH THE HUMAN RIGHTS GROUP CODEHUPY OUTSIDE CAAGUAZU PUBLIC PROSECUTOR’S OFFICE, 3 MARCH 2022. FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: JUAN RIVAROLA, ABEL ARECO, AND FULGENCIO TORRES. GLOBAL WITNESS

One

official who experienced this first-hand is Eresmilda Román Paíva, a judge in

the city of Itakyry, located

20km north of Ka’a Poty in Alto Paraná. Román began work as a magistrate in 1995.

Twenty years later, a case landed on her desk that would change her life

forever.

“In 2015, an Indigenous chief brought a lawsuit to my

court,” Román begins. This leader was having trouble with a Brazilian farmer

who was cultivating soy on his community’s land. The farmer had rented land

from the leader’s predecessor, but the new leader felt the arrangement was

exploitative and wanted the land back.

It didn’t take Román long to reach a conclusion.

Paraguay’s constitution prohibits the renting of Indigenous land, and

the arrangement hadn’t been approved by Paraguay’s Indigenous Institute. “I

annulled the contract,” she says, "and returned the land to the

community."

Before issuing her final ruling, however, she began

receiving threats from the soy farmer’s lawyer, Nelson Alcides Mora. “He even

put it in writing,” Román says, showing a letter, signed by Alcides, in which

he warns that “magistrates who act in a similar fashion end up in a Jury for

the Prosecution of Magistrates.”

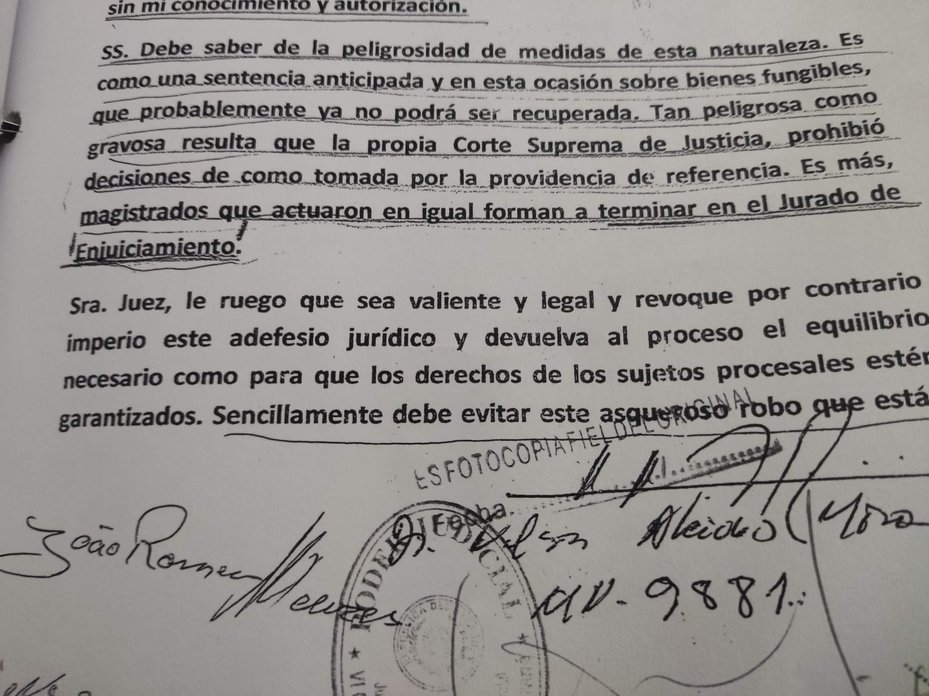

EXCERPT FROM A LETTER FROM A SOY FARMER’S LAWYER TO JUDGE ERESMILDA ROMÁN PAIVA, THREATENING TO DENOUNCE HER TO BEFORE A ‘JURY FOR THE PROSECUTION OF MAGISTRATES’. SUPPLIED BY ERESMILDA ROMÁN PAÍVA

Román, though, takes the responsibility of her position

seriously. She refused to bow to the lawyer’s pressure and ordered that the

land be returned to the community.

It was then that her problems really began. First,

Alcides appealed her ruling and succeeded in getting it overturned. Then he

acted on his threat, denouncing Román before a professional tribunal.

Simultaneously, he pursued a defamatory media campaign, claiming she’d

corruptly pocketed money by stealing his client’s soy, she reports.

Through the next seven years, Roman awaited a verdict on the

case. Every day, the threat hung over her: the arrival of a letter or phone

call that would banish her from her profession, destroying the career she’d

spent almost three decades building.

In December 2021, the rights group CODEHUPY intervened in the case,

alerting the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers

and presenting an Amicus Curiae before the Paraguayan courts. Eventually, in

October 2022, the pressure bore fruit, and the case against Eresmilda was

finally dismissed. “It causes psychological damage to be left

waiting so long," Román says. “I always feel it here, like a Sword of

Damocles, a blade close to the top of my head that doesn’t allow me to move.”

Our investigation

reveals how millions of consumers across Europe are likely contributing to the

forced eviction, poisoning, repression, and criminalisation of Indigenous and

campesino communities in Paraguay.

By combining

shipping data with insights from insiders across the soy, meat, and animal feed

industries, Global Witness traced the connections between the conflicts

documented in this report and European companies. First, we

tracked the flow of soy from the plantations producers engaged in conflict with

Indigenous communities to the silos and port facilities of ADM and Cargill. We

then charted its journey across the Atlantic, to feed firms, meat producers,

and finally the retailers and restaurants who sell products containing

Paraguayan soy to consumers across Europe.

Millions of consumers across Europe are likely contributing to the forced eviction, poisoning, repression, and criminalisation of Indigenous and campesino communities in Paraguay.

Europe driving demand

Europe imported 34.3 million metric tonnes of soy in 2019,

including around two-thirds from South America.

Greenpeace research indicates that the same year Europe mobilised nearly 12 million hectares of land abroad to meet its demand for soy for animal fodder.

The continent plays an outsized role as a source of demand

for Paraguayan soy, and for years the

European Union (EU) has been Paraguay’s number one export market.

Soy

grown in Paraguay enters Europe in two main ways, directly and indirectly. The

majority, around 1.1m tonnes in 2019, is imported with Paraguay as its recorded

origin, principally as soymeal, a course flour produced by crushing soy beans.

Within Europe, Poland, the UK, and Denmark are the biggest

buyers of soymeal directly from Paraguay, with Italy also playing a major role

in some years.

In 2021, UN COMTRADE reports that Poland imported just under 372,000 tonnes of

Paraguayan soymeal, the UK 290,000 tonnes and Denmark 70,000 tonnes.

However, the actual volumes of Paraguayan soy imports into

Europe are likely far higher, and its end-destinations and use within Europe

more nuanced.

Beyond direct imports, in 2019, for example, a further 0.7

million tonnes was likely imported into Europe mixed into the 7.7 million

tonnes of soymeal Argentina supplied the continent, as over 3.3 million tonnes of soybeans grown and harvested in Paraguay were processed in Argentina’s vast

crushing industry, and then reexported as Argentinian soymeal.

As such, in 2019/2020 Europe likely absorbed about 1.8

million metric tonnes of Paraguayan soy – over 5.2% of imports – significantly higher than Paraguay’s roughly 3% contribution to global soy production.

Europe has been a

key driver of soy expansion in Paraguay, with around 615,000 hectares of Paraguayan land occupied to produce soy for the continent – an area four times the size of Greater

London, or nearly four times the area of Paris, Berlin, Brussels and Rome

combined.

Europe has been a key driver of soy expansion in Paraguay, with around 615,000 hectares of Paraguayan land occupied to produce soy for the continent – an area four times the size of Greater London, or nearly four times the area of Paris, Berlin, Brussels and Rome combined.

Additionally, within Europe, the UK is a particularly big

source of demand for Paraguayan soy, which contributes a far higher proportion

of the UK’s overall supply than direct trade suggests.

Data provided to the Agricultural Industries Confederation

(AIC) by key traders including ADM, Cefetra, and Cargill, which includes

indirect imports via European member states, indicates that the UK actually

imported

375,215 tonnes of Paraguayan soybean meal equivalent in 2020, and 371,000 tonnes in

2019, making up 15.6% and 16% of soy for animal feed imported into the UK in

those respective years.

The UK’s huge apparent use of Paraguayan soy is driven by

demand for the chicken sector, and likely to a significant degree by the UK’s

biggest chicken firm, 2 Sisters.

Charting secretive shipments

A SOY BARGE HEADS UPSTREAM PAST THE CAIASA SOY PORT BUNGE SHARES WITH OTHER TRADERS ON THE RIVER PARAGUAY, SOUTH OF ASUNCION. GLOBAL WITNESS

Paraguayan soy’s precise routes into European supply chains

are veiled behind secretive transshipments at mammoth transit terminals in

third countries, principally in Argentina. Most available trade data does not

illuminate who ships what to whom, where or when.

But our research has pierced that veil.

As a land-locked country, almost all Paraguay’s soy harvest

leaves the country by river.

Growth in soy exports has propelled rapid development in the

country’s fluvial infrastructure: in the last 30 years, its fleet has grown fifty-fold, from 100 to 5,000 ships.

Such development has made Paraguay “the undisputed leader in river navigation

in Latin America, and the third in the world, after the US and China.”

By 2016, Paraguay had 26 river ports dedicated exclusively to moving soy: 16 on the banks of the Paraguay river, and ten on the banks of

the Paraná river. The biggest concentration looms over the Paraguay as it skirts the west of

Asuncion. Cargill (Port Union), ADM (Port Sara), and Russian giant Sodrugestvo

(SARCOM) all operate private ports in this area, while a huge processing plant

and port named CAIASA is shared between US giant Bunge, French trader Louis

Dreyfus Company, and COPAGRA, the Paraguayan subsidiary of Argentinean

agribusiness behemoth AGD.

ADM’S PORT SARA, 40KM SOUTH OF PARAGUAY’S CAPITAL CITY ASUNCION, FROM WHERE THE COMPANY BARGES SOYBEANS AND SOYBEAN MEAL FOR EXPORT. GLOBAL WITNESS

At these and other ports, soy is loaded onto barges for the

long journey downriver. Their destination is usually the Argentine city of

Rosario, the biggest soy export hub in the world, where ports and processing

plants line 70km of riverbank.

Here, the commodity traders operate ports for transshipping

Paraguayan soymeal: ADM has a facility named Muelle El Tránsito, Cargill has Muelle Quebracho, and Bunge and COPAGRA/AGD share a site called Terminal Six. Further downriver, ADM also operates a transshipment terminal in Nueva Palmira,

Uruguay.

In Rosario, whole Paraguayan soybeans are crushed and

reexported as Argentinean soymeal, meaning

millions of tonnes of Paraguayan soybeans disappear annually into Argentina’s vast soymeal crush.

Paraguayan soymeal, meanwhile, is transferred at the traders’ transshipment

ports onto the huge bulk carriers which deliver it to buyers across the globe –

with Europe as the principal destination.

Our investigation tracked the journey of Paraguayan soymeal from the transshipment facilities of ADM, Cargill and Bunge to animal feed firms that supply two of Europe’s biggest meat companies: 2 Sisters, in the UK; and Danish Crown, in Denmark.

2 Sisters was founded in 1993 by Ranjit Singh Boparan, a butcher’s assistant who left school at 16. Since then, it has grown into the

UK’s biggest chicken manufacturer, processing more than ten million birds a week and supplying a

third of all the chicken products consumed in the country.

Paraguay is a key source of soy for 2 Sisters’ chicken feed,

following the firm’s own soy sourcing policy, which states: “Over many years

2SFG experience [sic] has been that Brazilian / Paraguayan soybean meal has

been of superior quality to alternative sources.”

This policy also states that all the soy in 2 Sisters’

chicken feed is supplied by three traders that dominate the flow of Paraguayan soy into Europe. These firms

are Cargill and ADM (the biggest and second biggest exporters of soy from

Paraguay respectively), and Cefetra Group, a firm with UK operations, that is

in turn owned by BayWa Group, a German headquartered agri-commodity, energy and

building materials giant. Cefetra has reported that 45% of its expected 2020 UK/Ireland soybean equivalent imports were of Paraguayan origin.

Our investigation uncovered multiple shipments of Paraguayan

soy to the UK by ADM, Cargill, and Bunge, including Bunge shipments to Cefetra.

The Paraguayan soy in these shipments is purchased by UK animal feed

manufacturers and used in the production of chickens which are slaughtered and

sold by 2 Sisters.

These feed firms include 2Agriculture – a sister company of

2 Sisters also owned by the Boparan family

– and ABN, a feed firm owned by AB Agri, part of Associated British Foods.

Smaller volumes also likely flow to 2 Sisters via ForFarmers UK, a subsidiary

of one of Europe’s largest animal feed conglomerates, ForFarmers BV. 2 Agriculture and ForFarmers UK recently announced plans to merge operations,

giving ForFarmers a bigger share of the UK chicken market via 2 Sisters

contracts.

With the exception of 2Agriculture, which did not respond to

our findings, none of these feed firms denied using Paraguayan soy from ADM,

Cargill and Bunge (via Cefetra) when supplying 2 Sisters’ poultry feed.

Our investigation uncovered two specific routes by which

ADM’s Paraguayan soymeal reaches 2 Sisters’ chickens: one via Portbury, in

south-west England; and one via Seaforth, next to Liverpool in north-west

England.

ADM: The Portbury Nexus

THE SHANDONG FU YOU OFF PORTISHEAD, BRISTOL, ENGLAND, ON 16 JULY 2022, 6 DAYS AFTER DOCKING IN PORTBURY DOCK TO OFFLOAD 24,200 TONNES OF PARAGUAYAN SOYMEAL FOR ADM. HUW GIBBY

On 10 July 2022, a 200-metre-long merchant ship named the

Shandong Fu You nosed into England’s Royal Portbury Docks. On board were 24,200

tonnes of Paraguayan soymeal, loaded three weeks earlier at ADM’s transshipment

port in Nueva Palmira.

The previous year, in 2021, two other ships had plied the

same route: the Mandarin Phoenix delivered 10,000 tonnes of soymeal from ADM’s

El Transito port to Portbury in December;

and the Amis Unicorn delivered 22,000 tonnes via the same ADM port in June.

From Portbury, ADM’s Paraguayan soymeal is trucked to a pair of feed mills operated by ABN in the pretty Devonshire villages of Uffculme and

Cullumpton, where it is mixed with other inputs like wheat and corn to produce

chicken feed for 2 Sisters.

This feed is trucked along narrow country lanes to the

region’s cluster of intensive poultry units. The flagship of these is

Swanhams, a chicken mega-farm operated by Hook 2

Sisters, a joint venture between 2 Sisters and the hatchery PD Hook. From

the front gate, Swanhams Poultry Unit is an inconspicuous series of six wooden

barns. A closer look, however, reveals that the wooden façade is maintained

only at the front, and that the corrugated metal structures stretch back for

over a hundred metres. Within each of them are

60,000 chickens, with the site

as a whole holding 350,000 at a time.

2 SISTERS’ PROCESSING PLANT AT WILLAND, IN THE UK, WHERE ONE MILLION BIRDS ARE SLAUGHTERED EVERY WEEK. GLOBAL WITNESS

These chickens spend five to six weeks in the

intensive poultry units before they’re ready for slaughter. Collected by “catching gangs”, they are stuffed into crates and stacked onto trucks for transport to 2

Sisters’ sprawling processing plant in the village of Willand, where a million chickens are killed a week.

Neither ADM, ABN, nor 2 Sisters refuted these

findings when put to them.

ADM: The Seaforth Nexus

Further up the English coast, 2 Sisters also

sources Paraguayan soymeal from ADM facilities in the port of Seaforth, near

Liverpool. So far in 2022, ADM has shipped at least 37,615 tonnes of Paraguayan

soymeal to Seaforth in two consignments from its transshipment terminal in

Nueva Palmira, Uruguay.

From Seaforth, ADM’s Paraguayan soymeal is

trucked to a nearby feed facility in Llay, North Wales operated by

2Agriculture, the sister firm of 2 Sisters.

From the 2Agriculture mill, chicken feed is

delivered to Hook 2 Sisters’ many sites in the area, including Treuddyn Poultry Farm and the firm’s cluster of intensive

poultry units in north-west Wales. Chickens reared at these sites are slaughtered in 2

Sisters’ flagship processing plant at Sandycroft, near Deeside, which also

kills a million birds a week.

SEAFORTH DOCKS, LIVERPOOL, WHERE ADM AND CARGILL HAVE RECEIVED SHIPMENTS OF PARAGUAYAN SOY ULTIMATELY USED IN CHICKEN FEED. A.P.S. (UK)/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Cargill

Cargill also ships Paraguayan soymeal to

Seaforth, via its Rosario transshipment hub of Muelle Quebracho. In 2021,

Cargill shipped almost 60,000 tonnes of Paraguayan soymeal in three

consignments to its facilities in Seaforth. As with ADM, Cargill’s soy, including that imported from Paraguay, is sold to

manufacturers of animal feed used in 2 Sisters’ chicken production, including

2Agriculture and ABN.

None of the companies that responded to our

findings refuted these supply chain links when put to them. ABN told us it uses

Cargill’s ‘Triple S’ certification scheme.

A substantial portion of Cargill’s UK soy

imports also feed the US giant’s own integrated chicken operation, Avara Foods,

a joint enterprise with the British producer Faccenda Foods. A recent

investigation by Unearthed found that soy from Cargill’s Seaforth plant is

trucked first to the firm’s poultry feed mills in Hereford and Banbury, and

then on to Avara chicken farms.

Bunge

Finally, Bunge also ships Paraguayan soymeal

to the UK. So far in 2022, the US giant has delivered three consignments

amounting to 18,260 tonnes to the Belfast facilities of feed ingredients trader

Cefetra. Cefetra in turn sells soy, including Paraguayan soy supplied by Bunge and

others, to firms fulfilling 2 Sisters’ animal feed requirements, such as ABN

and 2Agriculture. None of these companies refuted these supply links when put to them.

PIG CARCASSES HANGING IN DANISH CROWN’S HORSENS PROCESSING PLANT, DENMARK. ALASTAIR PHILIP WIPER-VIEW / ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Paraguayan soy reaches Danish Crown’s intensive pig farms via

another Nordic agribusiness giant, Danish Agro. Danish Agro is one of Europe’s

ten biggest animal feed firms, handling around

40% of Denmark’s soy imports and producing 2.8m tonnes of feed a year. ADM is its number one soy

supplier.

We

identified two shipments of Paraguayan soy from ADM’s El Transito port in

Rosario to warehousing facilities Danish Agro leases from Associated

Danish Ports (ADP) in

Fredericia, a port town on Denmark’s

Jutland peninsula. Totalling 48,000 tonnes, the shipments arrived in June and

December 2021: 20,000 tonnes aboard the Amis Unicorn, and 28,000 on the

Mandarin Phoenix.

From the docks, the soy is trucked to Danish Agro’s feed factories.

There, soy may be mixed with other inputs such as barley and wheat to make pig

feed, which is delivered to farms rearing pigs that supply Danish Crown’s network of slaughterhouses.

Danish Agro said it strongly disapproves

of human rights and land rights violations, which were contrary to its

requirements, and that it had contacted its main soy supplier, ADM,

and was awaiting the results of an investigation ADM was undertaking.

These slaughterhouses are also enormous sites; the firm’s

biggest is located in Horsens and kills 100,000 pigs a week, with meat-packing done in the same site.

THE MANDARIN PHOENIX WHICH DELIVERED 28,000 TONNES OF ADM'S PARAGUAYAN SOY TO DANISH AGRO IN FREDERICIA, DENMARK, ON 22 DECEMBER 2021. PETER WARD

Danish Agro’s principal rival in Denmark is DLG, another of

Europe’s biggest animal feed firms which imports 900,000 tonnes of soybean meal annually. Cargill shipped 11,500 tonnes of

Paraguayan soymeal to DLG in 2022, although DLG claimed it was not used for pig

feed so did not supply Danish Crown.

We also tracked a shipment of

30,000 tonnes of Paraguayan soy

from ADM on the Apogee Endeavour, which

unloaded on 22 April 2021

alongside facilities in Aarhus

bulk terminal that

multiple sources indicate are owned or controlled by DLG. However, while

DLG acknowledged the shipment occurred, it denied the soy

was delivered to it or to a facility that it owns or operates.

Like Danish Crown, both Danish Agro and DLG are also

cooperatives owned by Danish pig farmers, many of which may also be

owner-members of Danish Crown. Both feed firms have agreements with Danish

Crown under which data on animal feed volumes and ingredients and pig sales to

Danish Crown are monitored and shared.

2 Sisters’ chicken and Danish Crown Group’s Danish-originated

pork are ubiquitous on high streets, supermarkets shelves, and in restaurant

chains continent-wide, and consumed by tens of millions of European consumers

every day.

2 SISTERS’ CHICKEN AND DANISH CROWN GROUP’S PORK ARE UBIQUITOUS ON HIGH STREETS; AT LEAST 26 MAJOR EUROPEAN RETAILERS SOURCE FROM THEM.

We identified three fast food chains using 2 Sisters’ chicken

in the UK, at least 10 UK retailers that sell or

until recently sold 2 Sisters and Danish Crown products, or using their meat,

and a further 13 major retailers across France, Germany and Italy selling

Danish Crown pork.

2 Sisters claims to supply Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) in

the UK.

Nando’s UK and Ireland and McDonald’s are both also 2 Sisters customers.

2 Sisters names UK retailers Aldi, Asda, Co-op, Lidl, Marks

& Spencer (M&S), Morrison's, Sainsbury's,

Tesco, and Waitrose among its customers in the UK, although

Waitrose told us it no longer sources from the firm. Frozen-food giant Iceland is also reportedly a customer.

These retailers

use 2 Sisters for their own-brand products. Examples include Tesco’s ‘Willow Farms' line, and

M&S’ ‘GastroPub’ brand of ready cooked meals.

TESCO’S ‘WILLOW FARMS’ BRAND OF CHICKEN, AND MARKS AND SPENCER’S ‘GASTROPUB’ BRAND OF READY MEALS, BOTH PRODUCED BY 2 SISTERS.

All these UK

retailers also sell products manufactured by Danish Crown or subsidiaries of

the group.

Danish Crown’s

tinned meat division, named Tulip, is one of the company’s best known operations,

producing over 130 million cans of meat annually.

Tulip is licenced by the US consumer goods

company Hormel Foods to produce its world-famous SPAM® brand of luncheon

meat for the European market. SPAM® is

sold by many of the UK’s biggest retailers, including Sainsbury’s, Tesco, Asda, Morrisons, Co-op, Waitrose, and Iceland.

Some UK supermarkets also offer products manufactured by

Danish Crown’s Tulip facilities under the Tulip brand itself, including

Sainsbury’s and Tesco.

Sainsbury’s includes Tulip Food Company in Vejle, Denmark,

in its January 2022 tier 1 suppliers list. Its own-brand tins of ‘lean ham’ and ‘chopped pork and ham’ are made in Denmark with Danish pork, and the

retailer did not deny these were made by Danish Crown.

Lidl lists four Danish Crown entities, including two in Denmark

(one of which is a Tulip facility) in a 2022 list of its suppliers.

M&S has also sourced cooked and sliced pork for its own-brand

products from Danish Crown’s Tulip division, and

although the contract reportedly ended in 2019, M&S did not deny continuing

to source pork from Danish Crown when contacted.

Aldi UK is also supplied by Danish

Crown.