A European loophole keeps nickel from Russian mining giant Norilsk Nickel flowing to the US long after Washington banned imports of the Russian-origin metal

More than three years into Russia’s bloody invasion of Ukraine, the EU has vowed to stand firm against Russian aggression. Despite collapsing US support, the bloc demands unconditional withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine before any sanctions are eased.

But when it comes to the metals crucial for the green economy, the EU has failed to keep pace with US and UK sanctions, revealing stubborn dependencies that undermine the coherence of the sanctions regime.

Trade data analysed by Global Witness shows that the EU has legally imported nearly $1.3 billion of Russian nickel since the US and UK sanctioned the metal in April 2024, with about two-thirds of this value going to Finland.

Russian rail freight data for the period April 2024-January 2025 showed that an average of 290 containers a month crossed the Russia-Finland border by rail.

While this legally-imported Russian nickel is likely entering Europe for use in EV batteries and stainless steel, it has also made its way from there to the US, with customs data analysed by Global Witness showing continued exports of European-refined, Russian-mined nickel to the US long after a US import ban was imposed.

Because it legally comes from Finland, US sanctions do not prevent such imports.

Sanctions gap lets Russian-mined nickel flow to Western markets

Download Resource

The data highlights Europe's key role in the production network of Russia’s giant mining conglomerate Norilsk Nickel, which continues to operate a major nickel refinery in Finland via a Finnish subsidiary, even while Russian troops build up on the Finnish border.

These trade ties also raise serious questions about the application of EU standards on human rights, as the bloc prepares to adopt new due diligence laws.

A sanctions gap

The EU’s sanctions gap around Russian critical minerals was laid bare in April 2024, when the US and UK banned imports of Russian-origin nickel, copper and aluminium. Though the term "sanction" was avoided in official statements, the import ban fits within the broader sanctions architecture imposed on Russia since 2022.

The UK government argued that metals were Russia’s largest export commodity after energy, and the ban would “prevent the Kremlin funnelling more cash into its war machine.”

The EU did not follow suit. Although the bloc imposed some aluminium restrictions in February 2025, metals such as nickel, copper and titanium remain unsanctioned.

One of the most economically significant is nickel, a metal vital for stainless steel production and the batteries used in electric vehicles (EVs).

While the EU has more than halved the share of Russian nickel in its imports since the Ukraine invasion, Russia still accounted for 15% of EU nickel imports in the second quarter of 2025.

Global Witness used shipment data and company disclosures to track this billion-dollar trade, from remote Arctic mines to buyers in both the EU and the US. We also traced products from Norilsk Nickel to some of Russia’s largest military suppliers.

Pollution and protests

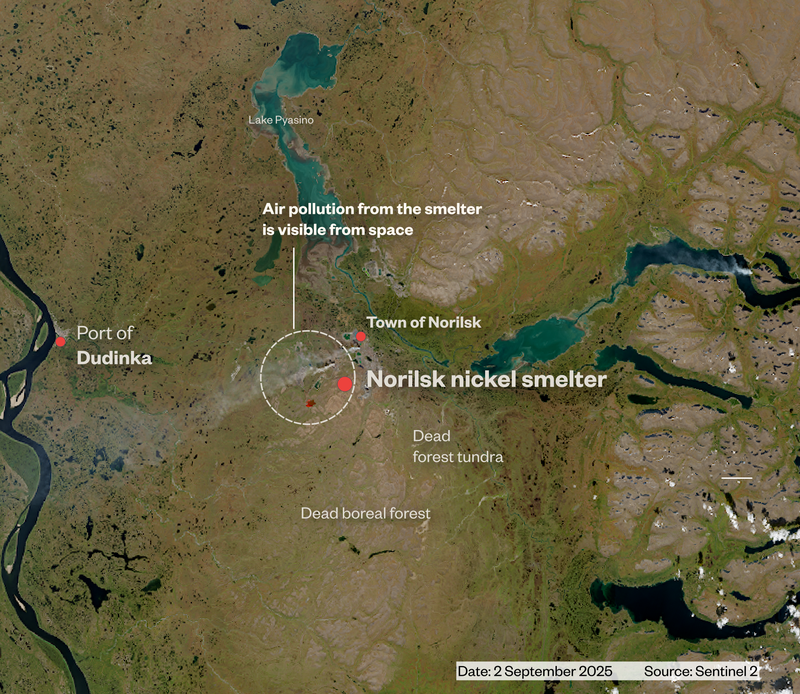

The path of Russian nickel to the EU begins 250 miles north of the Arctic Circle in Norilsk, the most northerly city on earth.

Norilsk is the company town of Norilsk Nickel, commonly known as Nornickel. This giant mining conglomerate is headed by Vladimir Potanin, Russia’s richest man and close associate of President Vladmir Putin. It controls nearly a quarter of the world’s refined nickel production, 40% of its palladium, and is a major producer of copper and platinum.

From its birth in the 1930s as a Soviet mining complex built on gulag labour, Norilsk became notorious as one of the most polluted places in the world. The town is surrounded by cavernous grey pits, slag heaps and a reddish tailings lake. It is closed to foreign visitors without a permit. Its smelter chimneys pour out huge clouds of sulphur dioxide.

These toxic fumes have created a fallout zone of dying forest that is visible from space.

The toll of Nornickel’s operations on the delicate Arctic environment around Norilsk has been compounded by devastating industrial accidents.

The most severe occurred in May 2020, when the collapse of a corroded storage tank flooded 21,000 tons of oil into local rivers, poisoning the fishing grounds of Indigenous communities whose ancestral lands surround the mine. The spill was one of the worst in Arctic history.

“The incident polluted two rivers and Lake Pyasino, turning waters red with contamination and devastating the fragile tundra ecosystem,” Arctida, an NGO focused on uncovering kleptocracy, environmental damage and violations of Indigenous rights in the Russian Arctic, told Global Witness.

The disaster galvanised Indigenous and civil society resistance to Nornickel, as well as scrutiny from Russian state regulators and buyers.

This pushed the company to make major reforms to its environmental management – including closing its most polluting plants in its secondary production hub on the Kola Peninsula, implementing a sulphur reduction program in Norilsk, and announcing new engagement processes with Indigenous communities.

When asked by Global Witness about their environmental record, Nornickel insisted that the previous negative depictions of their operations are outdated.

In particular, they pointed to their Sulphur Program, which they said has overcome huge engineering and logistical challenges to reduce sulphur dioxide pollution in Norilsk by 32% from 2015 levels. Norilsk’s sulphur emissions fell to 1.25 million tons in 2024, according to the data they shared.

The figure is still strikingly high, equivalent to around three quarters of the USA’s total sulphur dioxide emissions in 2023, which have roughly halved since 2015.

While Nornickel did make genuine advances after the 2020 oil spill, civil society appears to have played a crucial role in holding the company to account. Environmentalists monitored the impact of the spill, finding continued contamination of local waterways two years later.

In 2021, Nornickel established an Indigenous Communities Coordination Council and put in place a support policy with the stated aim of facilitating a direct dialogue with Indigenous peoples.

However, some Indigenous activists criticised this program. They alleged that Nornickel was co-opting Indigenous voices by selectively channelling funds to groups prepared to support its operations.

Russia’s wider Indigenous representation had already been distorted by a pro-Kremlin takeover of the country’s Indigenous association.

Critical activists campaigned to pressure key global nickel buyers not to associate with the company.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine and the picture went dark.

Silencing dissent

As Russia prioritised strengthening its war economy, it scaled back government environmental monitoring and relaxed ecological requirements on businesses facing sanctions.

From 2022, amid a new wave of state internet censorship, social media channels that used to post regular updates on environmental and safety concerns in Norilsk fell silent.

Simultaneously, the Kremlin moved to criminalise international environmental groups, including several that had long campaigned to improve conditions around the Norilsk mines.

A year after the Ukraine invasion, the Russian chapters of Greenpeace, WWF and Bellona were labelled “undesirable organisations”, forcing them to shut down work in the country.

The regime is determined to silence anyone who dares to challenge its abuses. This climate of repression makes due diligence in the country risky

In July 2024, Russia declared 55 Indigenous organisations “extremist” groups, then added them to the state’s “terror” list. Leading activists fled the country in fear of imprisonment.

“The regime is determined to silence anyone who dares to challenge its abuses,” Anna Jerzak, expert on Central and Eastern Europe at Greenpeace International, told Global Witness. “This climate of repression makes due diligence in the country risky and narrows the opportunities of civil society to resist environmental injustice.”

In Norilsk, the crackdown has left a due diligence paradox. Nornickel maintains a strong appearance of transparency, publishing extensive reports on its operations. But independent public monitoring has all but disappeared, and critique of its activities within Russia has been silenced.

In an emailed response to Global Witness, Nornickel said that criticism from outside Russia did not reflect the reality of their relationships with communities on the ground, which they described as constructive and supported.

The route to Europe

While most independent information from Norilsk has been cut off, its products continue to flow legally into Europe.

Although overall Russia-EU nickel imports are down, Russian rail freight data analysed by Global Witness show that the volume of Russian nickel moving over the Finnish border every month has increased slightly since the Ukraine invasion.

The journey begins when nickel matte from Norilsk’s smelters is loaded onto cargo ships in the port of Dudinka, on the Yenisei River just west of the town. The five cargo ships in Nornickel’s Arctic Fleet make regular journeys between Dudinka and Murmansk, on the Kola Peninsula in the far west of the Russian Arctic.

Nickel matte unloaded in Murmansk is moved by rail to Monchegorsk, about 100 miles from the Finnish border.

The Kola Peninsula is a secondary hub for Nornickel’s operations, including another huge mining site and the Kola MMC refinery in Monchegorsk. Since Nornickel closed its smelters in the region, locally mined nickel goes to China. But two pathways to Europe remain open.

In the first, nickel smelted in Norilsk and refined at Kola MMC is moved back to Murmansk for export by sea to global destinations, including EU countries. Kola MMC produces nickel sheets known as cathodes, most suitable for use in steel production.

In the second, partially refined nickel matte is moved by rail directly into Europe. Freight containers full of this material roll across the Finnish border at the tiny town of Vainikkala, to be processed in Nornickel’s refinery in Harjavalta, western Finland.

Harjavalta's crucial role is to supply Europe and partially America with products that are in demand there. This is a window for us to Europe, to the Western world.

This refinery is operated by Norilsk Nickel Harjavalta Oy, a wholly owned subsidiary of Nornickel incorporated under Finnish law. Around 94% of its feedstock comes from Nornickel’s Russian mines, according to the most recent available figures. It produces a wider range of nickel products, including briquettes and sulphates suitable for battery production.

“Harjavalta's crucial role is to supply Europe and partially America with products that are in demand there,” Potanin told Russian news agency Interfax in July 2024. “This is a window for us to Europe, to the Western world.”

The Harjavalta refinery has the capacity to produce up to 65,000 tons of nickel products every year – more than a quarter of Nornickel’s total output.

In the absence of European sanctions, Harjavalta’s operations are perfectly legal. But the supply chain they are embedded in is deeply opaque. Nornickel does not disclose its final customers.

A green dependency?

Shortly before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Nornickel, via its subsidiary in Harjavalta, seemed poised to integrate with Europe’s battery ecosystem.

In 2020-2021, Nornickel Harjavalta signed agreements with several European battery chemical manufacturers, including plans to supply a new battery precursor factory in Harjavalta to be built by German chemicals giant BASF.

Finnish state companies such as Fortum and Finnish Minerals Group expressed interest in investing in or collaborating with some of these joint ventures. However, most did not go ahead.

A year after the invasion of Ukraine, Nornickel Harjavalta became one of the nine founding members of the trade association Finnish Battery Industries, which is dedicated to establishing a battery production hub in Finland.

Nornickel Harjavalta remains a member in 2025, alongside major European companies including Umicore and BASF.

However, industry shifts and increasing opacity around trade with Russia cast doubt on the extent to which Nornickel remains an active participant in Finland’s battery sector.

Several of Nornickel’s prospective partners have exited the battery chemicals business, voluntarily divested from Russian nickel, or gone bankrupt. After a long delay, BASF’s planned battery precursors plant in Harjavalta finally received an environmental permit in 2024 but is not yet operational.

Nevertheless, Finnish journalist Pasi Peiponen, who reports on the Russia-Finland nickel trade for Finnish state broadcaster YLE, has observed that the plant’s infrastructure is physically connected to Nornickel’s refinery.

This makes it almost certain that if it were to go ahead in its current form, the project would escalate the use of Russian nickel in the EU’s EV batteries.

Global Witness reached out to BASF, Finnish Minerals Group and Fortum to ask about their current relations with Nornickel.

BASF said that no decision has yet been taken on whether their battery materials plant in Harjavalta will proceed. They said that the automative catalyst section of their business does source palladium from Nornickel’s Swiss subsidiary Metal Trade Overseas, in line with applicable laws, regulations and international rules.

Fortum said that they do not use nickel from Nornickel and have only supplied nickel cobalt sulphate solution to Norilsk Nickel Harjavalta Oy.

They said that proposals for a closer collaboration with Nornickel did not go ahead, and their battery recycling activities are focused on reducing the need for raw materials and supporting the European battery value chain.

Finnish Minerals Group said that they do not source from or collaborate with Nornickel.

Beyond batteries

While Finland’s battery industry provides a green context for the EU’s tolerance of Russian nickel, it is not the main beneficiary.

Trade data analysed by Global Witness suggests that most of Harjavalta’s production is for export.

A significant share of Finland’s unwrought nickel exports, of which Nornickel’s Harjavalta refinery is the only producer, appear in US import statistics. These list nearly $130 million of such imports since the US banned imports of Russian-origin nickel in April 2024.

The second largest declared importer, Germany, reports just over $50 million.

However, substantial volumes are routed through transit hubs such as the Netherlands, which makes the ultimate destination difficult to trace with certainty.

These figures suggest a loophole in the US and UK sanctions on Russian nickel. Neither the EU, US or UK has sanctioned Nornickel directly, and the US nickel sanctions exclude raw metal that has been “incorporated or substantially transformed into a foreign-made product.”

This means that regardless of where it is mined, nickel processed in Nornickel’s Harjavalta refinery legally counts as Finnish and can still be exported to the US. The London Metals Exchange (LME) lists the Norilsk Nickel Harjavalta Oy brand as “warrantable without restrictions,” implying that it is also exempt from UK sanctions.

Customs data analysed by Global Witness show exports of refined nickel from Norilsk Nickel Harjavalta Oy to US metals trader TMP Metals Group - which bought Nornickel’s US distribution subsidiary in 2023 - until at least September 2024.

The data also show numerous exports of nickel briquettes and cathodes – of which Nornickel is Finland’s only registered producer – by logistics company Dachser. These cargos were shipped from the Finnish port of Rauma, near to Harjavalta, via Germany to US destinations as late as August 2025.

When asked by Global Witness about these imports, TMP Metals confirmed that their company remains the exclusive distributor of Nornickel products in the US. They strongly rejected any suggestion of impropriety.

They said that they import refined nickel from Finland in full compliance with applicable laws, and that this business is intended to ensure uninterrupted supply of critical minerals in the US.

They pointed out that almost everywhere critical minerals are mined there are geopolitical, environmental and social problems, and that this is a paradox of modern society that relies on these materials for a range of essential applications, including the green economy.

They also pointed to recent improvements in Nornickel's environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance and argued that the company should be encouraged to continue working towards becoming an ESG leader.

Dachser did not respond to a request for comment.

European buyers of Nornickel’s Harjavalta products identifiable in customs data included Belgian materials company Umicore and Luxembourg-based commodity trader Traxys.

When asked by Global Witness about these purchases, Umicore said that they have a diversified metals sourcing policy that excludes Russian-origin nickel chemicals but includes limited volumes of nickel and cobalt products from the Harjavalta refinery in Finland. They stressed that they adhere to all laws, regulations and international sanctions, and condemn all acts of war and violence.

Traxys neither confirmed nor denied any commercial relations with Nornickel, but said that they comply with all relevant regulations and sanctions, are committed to transparency, due diligence and sustainability, and are proud of their ethical business conduct.

Nornickel’s direct supply chains of refined nickel from Russia to Europe are still more opaque. Other than Finland, the leading European importers of Russian nickel since April 2024 are Germany ($166 million), the Netherlands ($89 million) and France ($56 million).

On customs declarations, Nornickel lists the receivers of its European shipments as its own subsidiaries: two Swiss trading companies called Metal Trade Overseas AG and GPF Investments.

While the final buyers of these shipments are unclear, many are likely to be steel mills. The cathodes that make up most of Kola MMC’s production and part of Nornickel Harjavalta’s are not cost-effective to dissolve for battery chemicals but are a key input in stainless steel.

Global Witness wrote to several European steel mills understood to have suitable facilities to potentially be able to process Nornickel’s cathodes: BGH Edelstahl, Buderus, VDM and DEW Edelstahl (Germany), and Ugitech and Aperam (France).

Swiss Steel Group, the parent company of DEW Edestahl and Ugitech, said that none of its subsidiaries source any material from Nornickel, either directly or indirectly. Aperam said that their sourcing practices fully adhere to applicable laws, regulations, and ethical standards, but they could not disclose individual suppliers. None of the other companies replied.

Nickel and the Russian military

While Russian nickel remains unsanctioned by the EU, European companies are breaking no laws by buying it. But by doing so, they put money in the coffers of a company that is inextricably tied to the Kremlin’s war.

Nornickel is a major corporate taxpayer in a country where more than a third of state revenue now goes on military spending. Moreover, there is strong evidence that it directly supplies companies manufacturing military hardware used in Ukraine.

According to a 2023 Russian government report on critical minerals, shared with Global Witness by the Trap Aggressor project of the Ukrainian think tank State Watch, the main Russian consumers of nickel are stainless steel manufacturers involved in supply to the Russian military, many of which are under sanctions.

These include Severstal, a major supplier to Russian arms producers, and Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Plant, which partners with military truck manufacturer KAMAZ.

Given Nornickel’s near monopoly on Russian nickel production, it is almost certain that the company is central to meeting this demand.

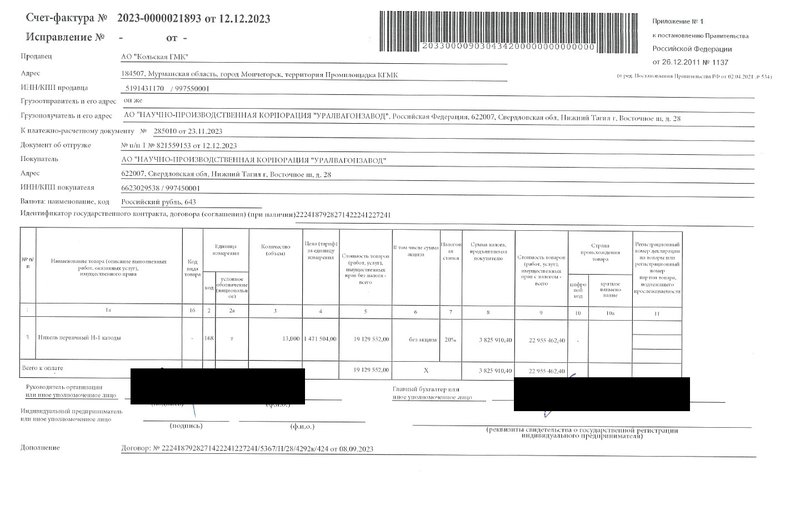

Leaked invoices obtained by Trap Aggressor and shared with Global Witness show payments in December 2023 for 27 tonnes of nickel cathodes, sold to Russian military manufacturer Uralvagonzavod by Nornickel subsidiary Kola MMC. The purchases totalled 48 million Russian roubles, then worth around $524,000.

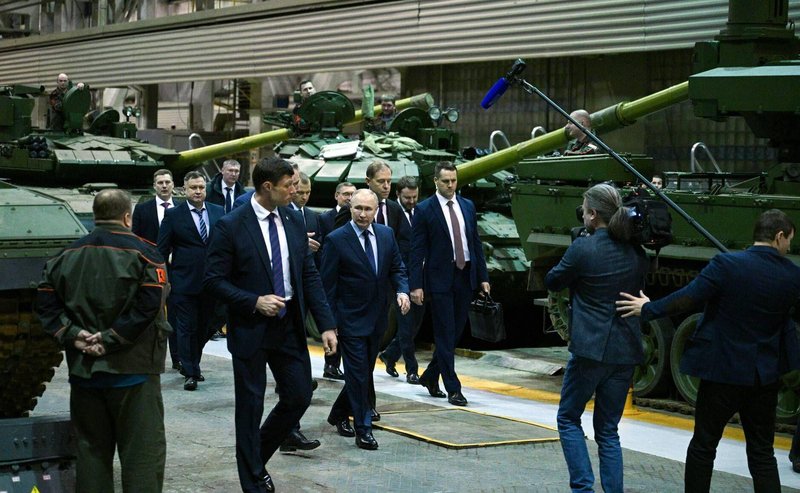

Uralvagonzavod is a Russian corporation that forms part of the state defence conglomerate Rostec. It produces and repairs tanks and other armoured military equipment, including the T-72B3M, T-80BVM and T-90M tanks used in Ukraine, where tens of thousands of people have been killed or injured by Russia’s invasion.

Global Witness asked all the companies named in this report about these ties between Nornickel and the Russian military. None replied directly to the question.

TMP Metals firmly rejected any association between its legitimate business and war financing or weapons production and said that its founder had supported global initiatives to bring about a peaceful resolution to the war in Ukraine.

As Nornickel looks to strengthen its position in Russia’s critical minerals sector, it is deepening ties with state corporations at the heart of Russia’s military machinery.

Two months after the Ukraine invasion, Nornickel signed a cooperation agreement with Russian state nuclear corporation Rosatom, focused on developing Nornickel’s Arctic transport corridors and launching joint ventures in critical minerals. These include the Polar Lithium project on the Kola Peninsula, Russia’s largest lithium mine.

Rosatom is a sprawling network of energy sector subsidiaries, with investments in nuclear projects and other ventures across the globe. It is also an important supplier of the Russian military, involved in the production of numerous Russian weapons systems.

The company is currently in control of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in occupied Ukraine, where it has been accused of abuses including torture. It has also expressed interest in developing Ukraine’s Shevchenko lithium deposit, captured by Russian forces in June 2025.

Thanks to its importance in nuclear energy supply chains, Rosatom is yet to come under Western sanctions.

A due diligence conundrum

Sanctions and due diligence

In 2024, the EU adopted the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). Under this directive, companies whose EU business meets certain thresholds will be required to identify human rights and environmental risks linked to their operations, take steps to mitigate these risks and provide remediation.

Unlike sanctions, which are highly political and must be agreed by all member states, the new EU directive allows civil society and affected individuals to challenge problematic corporate behaviour, independent of political and economic interests.

In the case of sourcing from a repressive regime such as Russia, it can act as an important complement to the sanctions program.

But the CSDDD is currently also under threat. In February 2025, the EU Commission reopened negotiations through the so-called "Omnibus on Sustainability" package, following a right-wing shift in the European elections alongside corporate and third-country pressure.

A debate is ongoing to raise the threshold for companies required to comply with the law from €450 million annual turnover and 1,000 employees to €1.5 billion annual turnover and 5,000 employees. The date by which companies are required to comply has been pushed back from 2027 to 2028.

The reopening of the CSDDD also threatens various key provisions, including the obligation to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence throughout the entire value chain, access to civil liability for communities affected by harmful corporate operations, and the ability to litigate against companies in EU courts.

It would also place limits on stakeholder engagement and consultations.

While sanctions remain beholden to economic agendas, once the new CSDDD law is transposed into national law by EU member states, the links between EU companies and Russia's corporate giants will come under renewed scrutiny.

For Nornickel, Harjavalta’s turnover alone would bring it within scope of the CSDDD as adopted in June 2024. Nornickel will therefore be subject to the supervisory authority of the country where its EU branch is based, Finland, which must monitor compliance with its due diligence obligations under CSDDD.

Big European buyers of Nornickel’s products would also be obliged to conduct due diligence on the company. Even under the weakened legislation proposed in the 2025 “Omnibus” package, large companies like BASF and Umicore would still meet the thresholds.

All companies within the scope of the CSDDD will have to identify and publicly report on the risks they may be associated with and take action to mitigate them.

The context in Russia makes a mockery of the ideal due diligence process, which assumes some degree of openness and stakeholder engagement.

In a country like Russia where dissent has effectively been criminalised, it is arguable whether such measures are possible.

“The context in Russia makes a mockery of the ideal due diligence process, which assumes some degree of openness and stakeholder engagement,” the NGO Arctida told Global Witness.

“Unless Russia’s political situation changes or there is some international monitoring mechanism allowed, any due diligence will be based on incomplete information.”

Global Witness wrote to all the international ESG agencies listed on Nornickel’s website as having rated the company.

Only EcoVadis replied. They confirmed that they have suspended ratings of Nornickel due to the Ukraine war, as have most if not all other agencies on the list.

Their most recent ratings reveal that between 2020 and 2024, Nornickel registered an unacceptably low score or severe adverse events in at least one of EcoVadis’s four themes: Environment, Labor & Human Rights, Ethics, and Sustainable Procurement.

Due to confidentiality policies, the agency was unable to say where Nornickel had fallen short.

In 2023, Nornickel performed a self-assessment according to the standard defined by the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA), widely recognised as the most comprehensive in the industry. It declared itself to reach the level of IRMA Transparency – the lowest rating available, suggesting the company had failed to meet IRMA’s key standards.

While IRMA encouraged Nornickel to undertake the self-assessment, it has stressed that it cannot audit the result, having suspended engagement in Russia following the Ukraine invasion.

"An audit requires participation of stakeholders and rights holders and for that participation to be free from coercion, manipulation and fear of retaliation,” Scott Sellwood, civil society sector lead at IRMA, told Global Witness. “Those conditions were not there.”

Nicolas Bueno, a legal scholar and CSDDD expert consulted by Global Witness, explained that the CSDDD requires companies to consult stakeholders throughout the due diligence process. Where this is not possible, companies must also consult with experts who can provide credible insights into actual or potential adverse impacts.

“This is the case in the repressive context in Russia,” he concluded.

When asked by Global Witness about their ESG ratings, Nornickel noted that many Western ratings agencies have unilaterally refused to work with Russian companies, including Nornickel.

They said that they perceive this as an inability or unwillingness to operate objectively in the current geopolitical climate and to report the true state of Nornickel’s ESG performance.

They declined to publish their self-assessment under the IRMA standard but said they believe their own ESG disclosure reports provide an adequate overview of their ESG performance.

They said that their human rights and supply chain due diligence systems integrate standards from international bodies and they are confident that these provide a strong foundation for CSDDD compliance.

Of the companies consulted by Global Witness who acknowledged a commercial relationship with the Nornickel group, all said that their ESG policies align with international standards.

Umicore said that they have a CSDDD-compliant and third party-audited Sustainable Procurement Framework, including a specific policy for nickel.

However, none of the companies addressed specific questions about the challenges of applying these policies in Russia’s current context.

The nickel dilemma

The EU’s nickel dilemma has no easy answers, showcasing the pitfalls in the mineral-heavy model for the energy transition.

Sanctions are designed to hurt their target more than the imposer, and the EU’s failure to sanction Russian nickel is a tacit admission that the bloc is dependent on Nornickel.

Although the world’s largest nickel producer is now Indonesia, production there is also rife with ethical issues, including land grabs, deforestation and massive pollution.

Indonesia’s laterite deposits contain a low-grade nickel that requires energy-intensive processes to refine, meaning that high-grade sulphide deposits such as those in Russia and other northern countries are particularly valuable in the West’s efforts towards carbon reduction.

This is an advantage that Russia is willing to exploit. In September 2024, Putin threatened to restrict exports of nickel, titanium and uranium, in retaliation to Western sanctions. The threat underscored the danger of continued reliance on such a hostile partner for materials central to the West’s green transition plan.

But simply cutting off Russian raw nickel imports would be insufficient to prevent Russian nickel from entering Western supply chains.

As sanctions have tightened and some Western companies have voluntarily boycotted Russian metals, Nornickel has increasingly diverted sales to China, which already dominates global mineral processing and battery production.

Nornickel has discussed plans to move major copper smelting facilities from Norilsk to China, and has reportedly held talks with Chinese companies to supply 50,000 tons of nickel matte a year to a new Chinese plant processing nickel for the battery industry.

These products are also sanctions-exempt, under the same clause that excludes material “substantially transformed into a foreign-made product.”

For this reason, sanctions on Russian nickel that do not address this embedded material would harm European producers while failing to prevent Russian metals entering Europe via Asian-made battery materials and EVs.

Anton Berlin, Nornickel’s vice president for sales, has stated that Nornickel’s plan is to “integrate into the battery sector,” ensuring that the company “cannot be taken out of the global economy.”

Below, we set out recommendations to reduce dependencies on problematic Russian nickel and to ensure that sourcing the critical minerals key to the energy transition does not offload the costs onto marginalised peoples, or the victims of authoritarian regimes and war.

Policy recommendations

EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive

Scope

- Maintain existing thresholds: Retain the current scope of the CSDDD by upholding the threshold of 1,000 employees and €450 million in global turnover for EU companies, and €450 million in EU turnover for non-EU companies. Expand coverage to additional companies during a future review of the Directive.

- Preserve Member State flexibility: Avoid a fully harmonised approach that would prevent Member States from adopting more ambitious due diligence requirements.

Value chain coverage

- Apply a risk-based approach: Ensure due diligence obligations follow a risk-based approach, grounded in the principles of severity and likelihood of adverse impacts.

- Apply this approach across the entire value chain without limiting it to direct business relationships as most adverse impacts are likely to occur further down the value chain.

- Avoid placing limits on SME data: Do not introduce a cap on the retention of information sourced from SMEs to ensure robust due diligence efforts are supported.

Civil liability

- Establish an EU-wide regime: Introduce a harmonised civil liability framework at EU level, incorporating an overriding mandatory principle that allows for the application of the law of the Member State where the trial takes place.

- Enable representative action: Provide for the possibility of representative legal actions by NGOs and trade unions.

- Ensure access to justice: Reintroduce a minimum limitation period of at least five years for victims to bring forward claims.

Stakeholder engagement

- Broaden stakeholder definition: Adopt an inclusive definition of stakeholders to support meaningful engagement and more comprehensive risk identification.

- Enable CSO engagement: Allow civil society organisations to engage in stakeholder engagement to enhance the due diligence process, particularly in cases where directly affected stakeholders are unable to engage.

- Guarantee protection: Strong safeguards must be in place to protect the anonymity and security of stakeholders, particularly where engagement may lead to safety risks.

- Provide best practice guidance for high-risk contexts: The EU Commission shall provide guidance and outline best practices for safe stakeholder engagement in conflict-affected and high-risk areas, as well as in authoritarian contexts where engagement may be particularly challenging. This includes jurisdictions such as Russia, where local communities and human rights defenders are at an increased risk of attack.

Climate transition plans

- Mandate implementation: Maintain the obligation for in-scope companies to implement climate transition plans aligned with the Paris Agreement and the 1.5°C target.

- Require immediate action: Ensure that implementation begins without delay and avoid provisions allowing deferral or postponement.

Sanctions and trade measures

Introduce a targeted EU sanctions package on Russian nickel and associated refined products

- Ban imports of Russian primary and refined nickel and nickel-bearing intermediates.

- Freeze EU assets and transaction access of the Russian entities most closely linked to nickel production as well as key corporate affiliates that enable refining/export.

- Prohibit EU firms from providing services such as insurance, finance, shipping, and technical services that materially facilitate Russian nickel exports.

- Coordinate measures with US/UK to ensure coherence.

Close obvious circumvention routes

- Block transhipment/triangulation by requiring origin documentation and chain-of-custody declarations for nickel imports. Increase customs inspections of suspect consignments.

- Impose secondary sanctions-style measures for EU service providers that knowingly enable sanctioned supply chains.

Targeted carve-outs and transition support

- Allow time-limited, tightly controlled exemptions for critical non-substitutable civilian uses where immediate disruption would cause disproportionate harm; but only under strict licensing, transparency and auditing conditions and with short sunset clauses.

Use public procurement as leverage

- Exclude suppliers who source critical minerals from sanctioned entities or from jurisdictions where credible due diligence is impossible. Make procurement conditional on verified, independent chain-of-custody.

Circularity and demand-reduction through product design

Ensure circularity for critical minerals is a strategic priority

- Set mandatory design-for-repair and design-for-recycling standards for batteries, EVs, consumer electronics and stainless-steel products that heavily use nickel.

- Uphold the batteries regulation and require battery manufacturers to disclose material composition and recyclability metrics and to design modules for easy disassembly and high-value metal recovery.

Accelerate adoption of low-nickel battery chemistries

- Fund and fast-track grants/loan guarantees for OEMs and cell manufacturers to scale LFP and other low-nickel chemistries for segments.

- Provide temporary purchase incentives for low-nickel EVs and storage to stimulate market pull.

Strengthen Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and recycling targets

- Raise minimum recycled content requirements for batteries, stainless steel and selected alloys.

- Mandate producer take-back schemes with certified recycling facilities and third-party audits of recovery rates and material purity.

Support circular supply chains and domestic recovery

- Invest in EU-based advanced recycling infrastructure, hydrometallurgical refining for battery materials, and R&D into direct recycling to reduce dependence on primary nickel imports.

Protect Indigenous Peoples and communities at extraction frontlines

Make human rights & FPIC central to any EU policy on critical minerals

- Require Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) as a legal condition for EU corporate contracts, public finance, and trade preferences linked to mineral imports. FPIC must be independently verified and not by company-run processes.

Guarantee access to remedy and justice

- Keep and strengthen CSDDD civil liability provisions so affected Indigenous People and communities can pursue legal redress in EU courts. Provide legal aid funds and support for cross-border litigation.

Condition EU finance and investment on Indigenous safeguards

- Make EU investment, export credit, and development finance conditional on demonstrable human rights protections, independent monitoring, and benefit-sharing agreements negotiated with Indigenous Peoples.

Sanction complicity in repression

- Add individuals and corporate directors implicated in the criminalisation or violent repression of Indigenous groups to targeted sanctions lists.

Sanctions gap lets Russian-mined nickel flow to Western markets

Download Resource