Nickel mining has been expanding in Indonesia's Raja Ampat, fuelled by the world's demand for EV batteries – but Indigenous communities are campaigning to protect their home and its critical ecosystem

He hangs in the clear water, studying the blue below. Then he tilts his body forward, reaching down and kicking steadily, long spear before him. Soon, his white fins are just faint flicking shapes in the deep.

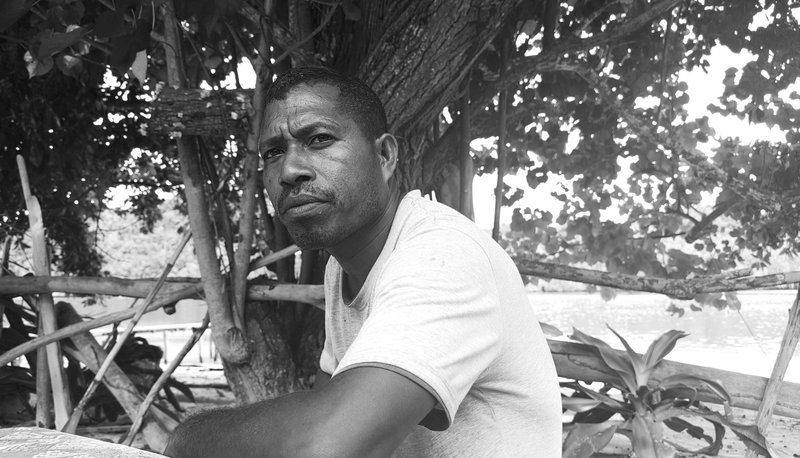

Lindert Mambrasar, freediver and fisherman, does this again and again. An hour later, one glistening fish and then two are pulled off the tip of his spear by his friends waiting in the boat. It is more than enough for supper tonight.

Lindert Mambrasar freediving off the coast of Manyaifun island, February 2025. Global Witness

Here, close to the shore of the island of Manyaifun and its sister island Batang Pele in the Raja Ampat archipelago, West Papua, the water is clean and the fish easy to spot. These thriving reefs have been called the “crown jewel” of the Coral Triangle – the name scientists have given this area of Southeast Asian seas that sustain the richest marine ecosystem in the world.

Powerful currents and trade winds form where the eastern Indian ocean meets the western Pacific. They nurture manta rays, green and hawksbill turtles, dugongs, dolphins, sharks and more species of coral and coral reef fish than anywhere else on Earth.

Scattered around 4.6 million hectares, Raja Ampat was awarded UNESCO ‘Geopark’ status in 2023 to celebrate and support its unique geology and culture. A network of marine protected areas cover more than 2 million hectares of its waters. Its landscape appears on the country’s highest-value 100,000 rupiah note.

Nickel mining comes to West Papua

Nickel is a mineral critical to the green economy as a key component of electric vehicle (EV) batteries and Indonesia has the largest nickel reserves in the world. It enters the supply chains of global giants such as Ford, Volkswagen and Tesla.

While industrial-scale nickel mining in the country began in the late 1960s, so far in Raja Ampat it has been largely limited to three small nickel-rich islands: Gag, Manuram and Kawe.

Operations here have been on and off for decades and have attracted controversy for their impact on the environment and communities.

After public pressure, on 10 June 2025 the Indonesian government revoked licences for four of the five mining companies operating in the archipelago. Local campaigners say they will keep up the pressure. They warn that it isn’t a complete ban – and that mining is taking place against the law on dozens of other small islands across Indonesia.

In Raja Ampat there has been a rapid recent expansion. Land use for mining grew by almost 500ha (roughly 1,220 acres) from 2020 to 2024, according to analysis of satellite imagery by environmental NGO Auriga Nusantara. This is around three times the rate of expansion from the previous five years.

Lindert holds a nickel shard, one of many found on his community's sacred beach, February 2025. Global Witness

Lindert and other members of the only village on Manyaifun island describe how, without warning, a team of surveyors turned up in October 2024. They employed a handful of local men to hack a trail through the forest covering the hills of both islands. The surveyors stayed for a month, but precisely what they found was never made clear to anyone they knew.

A mining permit had already been issued by the head of the province in 2013 which a source says happened without consultation with the community. It had lain dormant. Then in mid-February 2025, just before Global Witness investigators visited, a group of people believed by Lindert and others present in the village at the time to be from Indonesian-owned company PT Mulia Raymond Perkasa, which owned the permit, arrived in a speedboat.

Lindert believes that most people in Manyaifun are against mining. But the company had identified a few individuals who were in favour, he said, and held a closed meeting with them. Those who attended did not make those results known to the rest of the community.

A few weeks after the closed-door meeting Global Witness was told that a patch of forest on Batang Pele had been cut down and three timber-frame buildings put up. A community source believes this was a base for deeper exploration of the nickel beneath the trees.

Around the same time, a new 3,000ha nickel mining permit – an area almost 10 times larger than New York’s Central Park – appeared on the official Mineral One Data Indonesia government website for the nearby island of Waigeo – where rare birds of paradise are found.

The Wilson’s Bird of Paradise is only found in two locations in the world, both are in Raja Ampat. Michael Nolan/ Robert Harding / Getty Images

As fear among the island’s community deepened, they began to speak out. They depend on the ocean for fishing, its beauty to attract tourists and the land for food and fresh water.

Lindert says there are two freshwater springs on the island and if mining were to come, he says, the mata air (Indonesian for “spring”), will become air mata (“tears”).

West Papua is a former Dutch colony, ceded to Indonesia following an UN-endorsed referendum in 1969, which was criticised at the time for being unrepresentative. A strong movement of native Papuans still view the vote as illegitimate. The region is rich in resources – one of the world’s largest copper and gold mines is found here.

Around 70,000 people live in the Regency of Raja Ampat, speaking around a dozen dialects. A community of seafarers and traders, life here is largely based on or beside the water.

Our boat driver guides the boat towards a beach that the villagers on Manyaifun regard as sacred – and the men grow quiet. They believe the souls of their ancestors dwell in a ring of sacred stones in forest hills above. Lindert picks his way between the trees at the water’s edge until he finds the rocks he is looking for, scattered on the ground.

"Nickel,” he says, picking a piece up. “If the company comes then these sacred sites will be lost. It will be just memories.”

Lindert Mambrasar and activist Max Binur from Belantara Papua survey the nickel-rich hills of Manyaifun and Batang Pele, February 2025. Global Witness

Nickel rush

In 2023 Indonesia produced over half (52%) of the world’s mined nickel.

Already vital in creating alloys like steel, as global EV demand soars the International Energy Agency predicts that Indonesia will supply almost two-thirds of the world’s needs for the metal by 2030.

The government in Jakarta has made nickel a key part of its efforts to boost its economy, pursuing a deliberate policy of deregulation, tax incentives, subsidies and political support for mining companies and EV manufacturers.

By implementing a complete ban on the export of raw nickel in 2020 and requiring producers to purify it in Indonesia before shipping it abroad, it has engineered an increasingly complex extraction and processing industry.

Industrial parks host their own coal-fired power stations to fuel smelters and operations that create products from nickel pig iron for stainless steel to battery-grade nickel for the global EV market. Tens of billions of dollars, a considerable proportion from China, have been funnelled into the country and created jobs for tens of thousands of people.

Until now the nickel industry has been largely focussed on the Maluku Islands – sometimes known as the “Spice Islands” for their nutmeg, mace and cloves – and the island of Sulawesi.

Mines have been dug and giant industrial parks have sprung up along nickel belts, following the devastation of villages, coast and rainforest in Central Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi and North Maluku. These industrial parks supply nickel to steel factories and to battery factories owned by major EV suppliers like China’s CATL, GEM and Korean firm LG Chem and processing companies which supply the companies that make EV batteries.

Indonesian nickel ends up in electric vehicles made by the industry’s biggest players, and driven all over the world.

Indonesia produced over half of the world’s mined nickel in 2023, vital for EV production. Koiguo / Getty Images

Land rights abuses and a growing “ecological disaster”

This rush has brought intense conflict with communities whose ancestral land lies beneath the exploration zones. Evidence of land rights abuses and contamination of fisheries is piling up.

More than 75,000ha of forest has been cleared for nickel mines, according to environmental organisation Mighty Earth.

A recent investigation by the Gecko Project and partners accuses a major Indonesian mining firm of polluting the water source of a village for more than a decade through its nickel mining activities. Nickel compounds are known to be carcinogenic. Harita Nickel directed Global Witness to a statement on its website, which says it is working to improve its environmental and social governance.

The smelters used to process the mineral, fed by vast quantities of coal, are increasing Indonesia’s carbon emissions. Workers are dying in the smelters and people have been drowned in mining waste following the collapse of tailings dams.

There is a law banning mining on small islands like those in Raja Ampat, but it still goes on.

The limestone karsts of Wayag, close to a nickel mining site on Kawe. Global Witness

Indonesia's geology produces laterite ore deposits, which are found closer to the surface than deep sulphide deposits found in other countries such as Russia, Canada and the US. It is lower quality, requiring a lot of energy to process into high-quality nickel suitable for use in battery production. The most efficient way to mine it is through strip or “open cut” mining.

In tropical climates, this usually means razing rainforest with chainsaws and excavators, before loading the topsoil onto dump trucks, and storing it in piles or pits. In the heat and wet the soil can run off as sediment into rivers and the ocean, leading to increased pollution, landslides and floods.

Trucks and diggers appear tiny in an active strip-mining site on Gag Island, December 2024. Auriga Nusantara / Global Witness

Marine biologist Dr Phillip Dustan, who has studied coral reefs since the 1970s, including Raja Ampat, tells Global Witness: “When you go into a nickel mine and you scrape off the top layer, the system bleeds. It not only bleeds sediment, but it also bleeds all the nutrients that are in the biomass… The sediments smother the soil, the nutrients foster the growth of organisms that are faster growing than coral and can outcompete the corals. It is an ecological disaster.”

Studies have shown that coastal runoff is among the most damaging pollutants for coral reefs.

A man who travelled to this region more than 30 years ago, eventually making it his home, is known in the diving community as the “pioneer” of diving in Raja Ampat, Max Ammer.

Drawn here from the Netherlands by the prospect of exploring the sunken wrecks of World War Two fighter aircraft, he stayed and worked with the community to set up the region’s first dive resort and the non-profit Raja Ampat Research and Conservation Centre.

He calls the expansion of mining here “a very unwise idea”.

An experienced pilot, he has spent years flying over Raja Ampat’s islands, including Manoram where nickel mining has been going on for decades. He says he has seen “miles and miles of coral smothered by sediment” off the island's shores.

"I’m not against mining – as humans need to use the materials – but I’m against mining in an unfriendly way."

He says he has never seen it being done properly in the Raja Ampat mines – he is particularly worried about how the ore is extracted and stored.

“If you mine, you need hundreds of metres, if not several kilometres, between the coast and where you are doing things.”

Over half of the world’s coral reefs have disappeared in the last 70 years as they suffer from overfishing, climate change, and some negative impacts of tourism.

Deforestation and sediment spreading into the sea from Manuram island, December 2024. Global Witness

Tourism's "lifeblood" economy

Max's concern for Raja Ampat’s natural environment is echoed by the Indonesian Hotel and Restaurant Association, which in 2024 expressed alarm over the potential impact on tourism that the increased mining in Raja Ampat could have.

The extraordinary biodiversity draws tourists visiting “homestays” as paying guests of Papuan families in a traditionally built home, whether a stilt house over the ocean or a bungalow on land. These homestays are mostly in places with limited electricity, showers, alcohol or roads, and where phone signal is patchy.

The concept is fundamental to enabling island families to earn an income. It represents more than just money in the pockets of the hosts.

The Raja Ampat Homestay Association states: “Homestays are our way to defend our land… we do not want to be bystanders or someone else’s workers.”

In 2024 Raja Ampat attracted more than 33,000 tourists, according to Indonesia’s Central Bureau of Statistics.

Their impact isn’t all positive. Dr Dustan says the reefs are already being battered by human effluent contamination. But nickel mining is a growing threat to what he calls “the coral reef economy” – and he sounds a warning.

“Raja Ampat is the jewel of jewels,” he says. “You can’t destroy it… You’re not going to have a coral reef if you treat it the way it is. You won’t have an economy.”

A traditional ‘homestay’ in Manyaifun village, February 2025. Global Witness

Locals fear for Raja Ampat's "last paradise"

Manyaifun’s economy is based on the ocean. Forest-cloaked slopes fringe the cove where the only village is found. The water ripples with jumping fish and at night sparkles with phosphorescence. The fishermen leave each day before dawn and on their return, they meet a buyer who comes from the nearby port town of Sorong to buy their catch.

He pays 40,000 IRP per kilo, which is just over USD$2. Locals say that on a good day, they catch around 50 kg. If the weather is bad, the boats can't go out and the families earn nothing.

People here also live from what they grow in their gardens – sago, sweet potatoes and bananas. Most families have a coconut garden, and a buyer comes from Halamahera to collect their harvest for processing into coconut oil for soap, lotions and cooking.

Tourism offers additional income. The first homestay was created 15 years ago, now there are 10. Visitors from the US, EU and Russia come and pay around $40 a night.

A screen being made with local materials on Manyaifun, February 2025. Global Witness

"The Mamas" – the affectionate name for the women who run the household – Mary and Mina, have been preparing breakfast for homestay guests since 04:30. The room is hushed and dark, with the sun not yet up. A soot-blackened pot is suspended from a pole over the open flames. With practiced ease they prepare nasi goreng, Indonesian fried rice, and telur bumbu bali – spicy eggs.

“I really, really hope that mining doesn’t come,” says Mary Mambrasar. “The ocean, the coral will be destroyed, I can’t imagine how we will live.” She gestures towards the back door which opens over a lagoon and then straight on up to the mountains. “And the water? It comes from the mountains and the mountains will be the first to go.”

Outside, sitting at a wooden table on the edge of the beach, is Elias Meneri, from West Papua, who is training as a priest. He's lived on Manyaifun for two years.

He looks out across the water.

“Here the sands are white, the water is clear, fish often swim up to the sand and touch our feet… Raja Ampat is called a paradise, and a paradise is supposed to be beautiful… if that beauty is taken away, what then?”

"The fake energy transition"

Indonesia is made up of almost 20,000 islands, and 99% of these fall under the category of “small islands” as defined by law, according to Forest Watch International. Law No. 27 of 2007 regarding Coastal Areas and Small Island Management includes a limit on mining on islands with an area of 2,000 km² (200,000 ha) or less. The Supreme Court upheld this ban in 2024 despite a challenge by a mining company.

However, FWI found that 245,000ha of this land on small islands has been allocated to mining companies – covering 242 islands.

In an interview in his offices in Jakarta, Imam Shofwan from the advocacy organisation JATAM wears a T-shirt with a slogan in Bahasa that he translates as: “Your electric vehicle kills us.”

Imam Shofwan’s shirt reads “Your EV kills us”, Jakarta, February 2025. Global Witness

They say this is the solution to the climate crisis. In the field we have found that this is the new coal

"They say this is the solution to the climate crisis. In the field we have found that this is the new coal. They do open pit mining, and they are highly dependent on huge amounts of coal for processing… For us this is the fake energy transition."

Responding to the government’s apparent revocation of mining permits, Imam says:

“It’s because of the strong pressure from the public, not because of the good will of the government.”

He says that there are mining licences for 35 other small islands around Indonesia.

“Other small islands are suffering from nickel mining in southeast Sulawesi: Kabaena and Wawonii island. In Wawonii the mine continues to operate even after the citizens won the case in the Supreme Court.”

“We challenge the government to withdraw all those permits, not just the four in Raja Ampat.”

Along with the sprawling Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park (IWIP) in North Maluku the largest nickel processing operations in Indonesia are the giant Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) in Central Sulawesi, along with Obi Island.

Imam says that the Morowali and Weda Bay parks “have destroyed the land and the sea.” He believes that the same thing could happen to Raja Ampat.

The mining companies

There are five companies present in Raja Ampat:

- PT Gag Nikel has the active licence for Gag Island

- PT Kawei Sejahtera Mining was issued the licence for Kawe

- PT Anugerah Surya Pratama was issued the licence for Manoram

- PT Mulia Raymond Perkasa was issued the licence for Manyaifun and Batang Pele

- PT Nurham was issued the licence for Waigeo in February 2025

The shifting frontier

Travelling by longboat around Kawe we see several dive vessels anchored close by. One of the prime locations here is “Eagle Rock”, which a recent study showed was a critical “superhighway” for the globally threatened reef manta ray.

A diver watches a reef manta ray at the 'manta superhighway' Eagle Rock, close to the Kawe mining site. Global Witness

The limestone peaks of Wayag are to the northwest. Tourists flock to see its emerald peaks with hidden lagoons and beaches, a landscape Max calls “mind-bogglingly beautiful.”

Setting foot on Kawe’s deserted western shore, unbroken forest cloaks the slopes and white threads of waterfalls can be seen in the folds.

Follow the coast around to the east side and mining’s impact is clear to see in the sharp line where the crest of a hill has been sliced off and the brown stain below it. The centre of the operation, focussed on Kawe’s slender waist, has almost sliced the island in two.

Seen from above, the mining is revealed, December 2024. Auriga Nusantara / Global Witness

The 5,992ha permit (23mi2 or 59.92km2), was larger than the island, extending over the reefs surrounding it.

It was held by Indonesian company PT Kawei Sejahtera Mining (KSM) which was set up by a prominent – and controversial – figure in Papuan society and politics, Daniel Daat, and now appears to be run by his son John. The current licence was awarded in 2013 and would have been valid until 2033, though mining has been taking place since at least 2004. There have been reports of conflict between companies over ownership rights, and historic allegations of corruption.

Sediment smothers a coral reef beside Kawe during mining activity in 2008. Global Witness

Before the suspension of KSM's licence in June 2025, mining on Kawe had been picking up pace. In October, the acting Governor of Southwest Papua, Mohammad Mus’ad, took regional journalists with him on a working visit to the Kawe mine to discuss how local people can be employed. He was accompanied by the Deputy Commander of the navy in Raja Ampat, Colonel Mar David Candra Viasco.

KSM is backed by powerful interests. It counts among its directors retired Vice Admiral of the Indonesian Navy and ex-Governor of Papua, Freddy Numberi.

The President Director of KSM and a shareholder is a prominent figure in the Indonesian property industry, Ali Hanafia Lijaya. Media reports have linked Lijaya to a controversial 30km-long fence illegally installed in the sea just west of the Indonesian capital Jakarta, allegedly to pave the way for a major development.

The scandal is currently being investigated by police. Lijaya denies involvement.

According to internal company documents, the ore mined on Kawe was taken to be processed in Morosi, Konawe Regency in Southeast Sulawesi, which primarily produces nickel for the stainless-steel industry.

Kawe’s bay used to be a rich fishing ground, but we heard testimony from local people that the fish have now disappeared.

Sediment leaking onto the coral reef as nickel barges are loaded in Kawe bay, December 2024. Auriga Nusantara / Global Witness

Drone footage obtained in December 2024 by researchers working for local NGO Auriga Nusantara and Global Witness shows a slick of sediment flowing from a new pontoon with two mooring facilities.

Internal company documents confirm that this “terminal” is large enough to accommodate two 10,000 tonne barges, the size of vessels often used in Indonesia in shallow areas as short-haul transport to take their cargo to a larger vessel or directly to a processing centre.

The Gag Island mine

Gag Island is just a few kilometres outside the Raja Ampat Marine Park. It is around 6,000 ha in size, and the mining permit is 13,136 ha, larger than the island itself and extending over the reefs surrounding it.

It is operated by PT Gag Nikel, a subsidiary of the state-owned diversified mining company PT Aneka Tambang (Antam).

The quantity of nickel ore estimated to lie beneath its protected forest is significant. According to Antam’s 2024 Annual Report, it is estimated to contain almost 40m dry tonnes of nickel ore reserves.

Originally a joint venture between Antam and BHP Billiton, operations began in 1998. They paused in 2000 after the Indonesian government banned open pit mining in forests designated as protected, which included those that cover the hills of Gag Island.

After pressure from industry, there was a Presidential decree three years later which exempted the Gag Island mine from the ban.

Gag Island's forests are protected, but an exemption was given for mining, December 2024. Auriga Nusantara / Global Witness

But after years of operational delays and opposition by environmental and human rights campaigners, BHP Billiton pulled out in 2008. PT Gag Nikel started operations in 2018.

In October 2024, Antam, through its subsidiary Gag Nikel, bought a 30% stake in a Weda Bay smelter owned by PT Jiu Long Metal Industry, a subsidiary of the giant Chinese corporation Tsingshan Holding Group, the world’s biggest nickel producer.

Greenpeace International warned at the time that this deal would speed up the extraction of nickel on Gag Island.

Tsingshan produces high-grade nickel matte – a key precursor in the production of battery-grade nickel.

It has agreements to provide nickel matte to Chinese battery materials maker CNGR Advanced Materials, which in turn supplies global EV companies.

In June 2025 the Indonesian government exempted PT Gag Nikel from the permit revocation.

Choking Raja Ampat's mangrove forests

The intricacy of the tropical ecosystem in Raja Ampat means that the importance of the environment to the communities extends not just to the sea and the land, but to the in-between – to the mangroves that fringe many of the islands.

Mangrove forests perform an extraordinary array of tasks, keeping rising seas at bay, and protecting the land from storm surges. They are nurseries for fish, and they are powerful absorbers of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. However more than half of the world’s mangroves ecosystems are “at risk of collapse” according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Healthy mangrove forest close to Friwen island, February 2025. Global Witness

There is a base for mangrove conservation efforts in Raja Ampat on the island of Friwen, close to Cape Kri. Here one of the world’s most renowned marine biologists spotted 374 fish species on a single dive, celebrated by many as an unofficial record.

Sitting cross-legged on the floor of his office porch, Steve Wawiyai describes this as “base camp.”

We tried to do mangrove restoration in Gag Island, but the sedimentation had already covered the mangrove and the coral – the mangrove cannot live, there is constant sediment runoff

He set up the non-profit organisation Raja Ampat Coastal Friends Association (Kawan Pesisir Raja Ampat) in 2018, which uses satellite data to map existing mangroves in Raja Ampat – and where they have been lost.

Wawiyai sees nickel mining as a key threat. "We believe that 60% of the mangroves around Gag and Kawe have been destroyed."

“We tried to do mangrove restoration in Gag Island, but the sedimentation had already covered the mangrove and the coral – the mangrove cannot live, there is constant sediment runoff."

On a visit to Gag Island in June 2025, the Director General of Mineral and Coal (Minerba) of the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, Tri Winarno, said that “there was no sedimentation in the mining area.”

Steve criticises the construction of the jetty in Kawe, saying that there were mangrove forests all around the bay, but they were cut down to allow ships to land with heavy machinery.

“The people in Raja Ampat really need the fish,” he says, “they depend on the mangrove."

Loesye Ermy Fainno, February 2025. Global Witness

The mangrove is a complete food source – crabs live there, fish, there’s the fruit of the plant. It is a symbol of life for us

Steve’s wife Loesye Ermy Fainno, helps with the conservation work:

“For the Mama, the mangrove is a kitchen – it’s like going to the market, but for free. The Mamas have the responsibility to provide food for the family. The mangrove is a complete food source – crabs live there, fish, there’s the fruit of the plant. It is a symbol of life for us.”

She shakes her head: “No mining … If the ecology dies, we die too.”

Selfiana Manggaprouw, a social worker working with Coastal Friends says, “For us Papuan women we live by the sea – and must protect the sea.

“People are sleeping… We are helping them to wake up and see the future. They need to understand early. We must protect our land.”

Smelting for the energy transition, fuelled by coal

Along with nickel extraction, processing operations are also closing in on Raja Ampat, with plans advancing to create Papua’s first nickel smelter.

There is a $5 billion Chinese-backed project to build a smelter alongside a steel manufacturing plant in the regional town of Sorong. Chinese-owned PT Sheng Wei New Energy Technology has committed to building the smelter, while a second Chinese investor, Beijing Jianlong Heavy Industry Group has committed to constructing the steel plant.

The 500-ha site will be in the “Sorong Special Economic Zone.” Local investigators in Sorong say that people have started to see job adverts for positions connected to the project.

It will be “a new history” – according to the Stainless-Steel Council of China Oron and Steel Association.

The organisation, a sub-association of the China Iron and Steel Association, declares on its website: “The Sorong Special Economic Zone will introduce the world's most advanced nickel processing technology – oxygen-rich side blowing furnace technology (OESBF). The nickel processing plant will produce high-grade nickel matte, with a planned capacity of 160,000 tonnes... The products are planned to be exported to the United States, Europe and other markets.”

The Chinese-developed OESBF technology is a new way to process laterite nickel, with the first facility in IWIP developed by CNGR Advanced Material becoming operational in 2024. A second smelter opened in 2025 in Pomalaa, Southeast Sulawesi, jointly owned by Antam and CNGR Advanced Material, to supply nickel matte, which is more valuable to the EV industry.

The claim, which is difficult to verify as it is such a novel technology, is that it uses less coal, produces no toxic waste, and results in nickel matte. However, the process does still rely heavily on coal, which West Papua is rich in. Indonesian company PT Megapura Prima Industri operates a mine close to Sorong.

Piles of coal waiting to be transported out of the SEZ, February 2025. Global Witness

We drive past a “Welcome to the Sorong Special Economic Zone” sign, east of the city, and through the land where the infrastructure will be built.

Currently it is mostly covered by forest, and vivid green vegetation, with some farms. Cement, palm and coal are already here. A palm oil refining tower is visible, and there are piles of coal by the side of the road waiting to be transported.

Local media reports say the Chinese-backed smelter project is supported by the local government of Southwest Papua and will create some 3,000 jobs.

In May 2024 local media carried reports showing handshakes between the heads of three companies forming a consortium to advance the building of smelters: PT Malamoi Olom Wobok, PT Huahe Management Indo and PT Sino Consultant Investment Indo.

A key figure in the project is Adriana Imelda Daat, the Director of PT Sino Consultant. From West Papua, she is the daughter of Daniel Daat, the founder of PT Kawei Sejahtera Mining, which held the concession to mine Kawe.

In the Special Economic Zone, there is a small port where passenger ferries leave. From the pier it is possible to see a cargo ship docked at one of two larger ports to the south. According to a local source this is where nickel vessels would arrive and depart.

The view towards the SEZ southern dock where nickel ore could be shipped, February 2025. Global Witness

Also planning to invest in the Special Economic Zone is Indonesian company PT Trinitan Green Energy Metals. The company says that the “site is secured and partners chosen” to build a battery-grade nickel processing park called the IGNITE Ecopark and provide “Class 1 Nickel ensuring global industries meet their clean energy goals."

Class 1 is nickel with at least 99.8% purity. The company suggests that the source ore will come from Papua, highlighting the “+400m tons of Papua’s nickel resource.”

It states that it aims to produce 50,000 to 100,000 tons of Class 1 nickel per year.

While ground has yet to be broken, progress could be rapid. Driven by the ban on raw nickel exports, the number of Indonesian nickel smelters increased from a handful in 2014 to more than 50 in 2024.

Rise in nickel-based shipping

There has been an explosion in shipping activity around the two largest nickel-based industrial parks, Weda Bay (IWIP) and Morowali (IMIP).

New analysis by C4ADS reveals the average number of vessels anchoring within IWIPs port area per year increased by 1,620% in the four-year period before and after the January 2020 ban. For IMIP, the increase was 163.93%.

Perilous cargo

Nickel ore cargoes are seen by industry insurers as a serious hazard. It has been called “the world’s deadliest cargo” by experts because of its ability to shift from a solid to a liquid state under certain conditions. This can happen gradually, or without warning, and the risk is heightened during wet seasons when cargoes stored in open areas are exposed to rain.

A 2018 report by Norwegian marine insurance provider, Skuld, highlights poor standards of nickel ore shipping in Indonesia, saying that shipper’s obligations to ensure safe passage are “very rarely complied with” with certificates “often forged.”

This can have serious consequences for the environment. When a nickel barge near Morowali ran aground and spilled 7,000 metric tonnes of nickel ore in 2021 official figures from the Ministry of Maritime and Fisheries (KKP) indicate it damaged more than 2,000m2 of coral reefs.

We heard that the impacts of nickel industry shipping in Raja Ampat are already being felt. We travelled to the Fam Islands, which are made up of four main islands and several smaller ones. Between two of the islands, tucked into a calm lagoon, is a neat line of five wooden bungalows on stilts over the water. This is a homestay with space for 18 people. It’s full from December to February.

At first glance, this is an idyll. But sitting at a table under the shade of some coconut trees, Yahya Sawyai, whose brother owns this homestay, holds up his phone and shows us the route that ships take on a map.

The main shipping lane from Sorong to Gag Island passes the nearby island of Penem. This also means proximity to the vessels’ noise and vibrations.

Yahya says he has seen vessels carrying heavy machinery to the mine on Kawe. He says they disturb the habitat, driving away fish and dolphins.

“It’s intrusive, it upsets the fishes that are there… They’ve got to find food, but then there’s the sound of those large boats.”

Yayah Sawyai fears for the future of the Fam Islands, February 2025. Global Witness

A former student of Government Studies, Yahya has lived away from Fam, in Sorong and in Java. Several generations of his family have remained here. They used to organise the fishermen in the area and collect their fish and sell to a buyer in Sorong.

He claims that since the huge ships started passing by the catch has been dropping. They must fish further away, which uses more fuel. “The only choice is to stop the mining so we will not be facing this situation,” he says. “If we don’t reject it today then we will live with the consequences later.”

Yahya makes the same claim that we heard on other islands. No one from a mining company came to speak to the islands’ communities about the impact.

Sounds that come out of ships can be incredibly loud

Sophie Nedelec, a marine biologist from the University of Exeter, has spent more than 15 years studying the impact of noise pollution on coral reefs:

“The sounds that come out of ships can be incredibly loud, and they can propagate incredibly far – sound transmits better underwater than it does in air.”

She describes how it makes sea creatures extremely stressed and has an impact on how they develop throughout their lifecycle, for example by removing their ability to learn defence mechanisms and lowering their reproduction rates.

A thriving Raja Ampat reef; its inhabitants are vulnerable to noise pollution. Global Witness

She describes the expansion of nickel mining in Raja Ampat as “really upsetting.”

“Noise is something that I try to use to bring hope into the scenario because it’s a pollutant that we can limit at a local level as a way of increasing the resilience of life on the reef,” she says. “So, we really don’t want to be going in this direction.”

Sophie also highlights the impact that climate change and coral bleaching are already having on the once-resilient reefs.

Climate solution for whom?

The island of Mutus is one of those places most vulnerable to climate change. Approaching from the sea, the flat disc of green looks too small to be inhabited. Lozenge-shaped, it covers less than a square kilometre. Boats slip past a line of heavy blocks close to the shore, each the size of a refrigerator – protection for the narrow strip of sand and houses built right up to its edge.

While nickel is key to the transition away from humanity’s dependence on climate-heating fossil fuels, the people here don’t want their island to be a casualty in the decarbonisation race.

The man who speaks for the island’s 100 families, some 500 people, is their chief, Martillus Demarra. He was born on this land and has lived here all his life.

Martillus Demarra is the chief of Mutus island, February 2025. Global Witness

“We already feel the impact of climate change,” he says. “The weather is unpredictable. Sometimes we get more fish, sometimes less… If the government says nickel is the solution for climate change, we believe it’s rather contradictory.”

He believes that among his people, it will only create more victims.

“We must oppose the mining,” he says. “If it happens, we will lose our lives."

Echoing the other people we have spoken to in Papua, Martillus says that no one from any mining company came to talk to him.

The people of Mutus depend on the ocean, February 2025. Global Witness

We don’t need electric cars… What do we use here? We use oars!

On the day we speak, a regional church convention happens to be taking place in Mutus. We meet John Warmasen, a regional religious leader. His voice is barely audible over the rain, but the message is clear:

“We live in small islands; we don’t need electric cars … What do we use here? We use oars!”

He says that the impact of mining on the sea and the land lasts “a long time – thousands of years. It’s not like we can just flip it like we flip our hands. It’s not something that we can hocus-pocus out of, and we’ll be done with it the next day.”

He calls on the existing companies to provide more work opportunities “to let the locals in, so they can benefit.” He and Martillus say that only three people from Mutus work in the Gag Island mine.

As for new mines opening, he says: “The government must respect the rights of people in Raja Ampat. It’s not just about human rights. It’s about customary and Indigenous rights. It’s not about people versus the company. It will be people versus people if mining comes… If the government doesn’t respect Indigenous and customary rights, there will be a big conflict."

Coercion and community consent

Max Binur founded the grassroots environmental campaigning organisation Belantara Papua.

In an interview in his office in Sorong, he tells us that he has watched the tactics of mining and logging companies for decades.

He sees a model of how they try to split a community.

In general, the majority won’t want mining, but usually there are one or two people “who make deals with the companies on behalf of the community and permit them to enter their land, but generally the community does not accept.”

A company will then use “state enforcers and security” to “coerce the community into agreeing to the company’s entry into their area.”

At the same time, it has become harder for anyone to oppose these impacts. This is partly because of the controversial pro-business Job Creation Law, known as the “omnibus law”, that was passed in 2020 despite mass street protests in Jakarta and other locations in Sumatra, Kalimantan and Sulawesi.

The omnibus law is designed to stimulate growth through deregulation. It rewrote more than 70 existing laws and expands the concept of projects of “national strategic importance."

The omnibus law has weakened the requirement for companies operating in Indonesia to consult those who may be affected.

This is despite Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) being an internationally agreed principle under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and accepted industry standards such as the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance.

Responding to the revocation of mining permits, Max said: “Permanent closure is not certain, because there will definitely be regulatory changes in Indonesia. Our advocacy continues to be to close the mining permanently in Raja Ampat.”

Recommendations

Global Witness worked with Satya Bumi and Belantara Papua to develop a list of recommendations.

To the Indonesian government

Policy actions

- Clarify why the ruling of the Indonesian Supreme Court in 2024 banning mining on small islands is not being adhered to, and why the limits on mining placed by Law No.27 of 2007 regarding Coastal Areas and Small Island Management is not being followed

- Immediately stop issuing new nickel mining permits in West Papua

- Immediately pause/stop all mining activity in Raja Ampat: designate it a ‘no go zone'

- Review Article 162 of the 2020 Mineral and Coal Law which allows criminalization/reprisals of communities who defend the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment as mandated by UN Resolution A/RES/76/300

- The Provincial Government of Southwest Papua is urged to promptly issue the recognition of Indigenous peoples' status, carry out the mapping of customary territories, and designate West Papua as a customary region in order to protect it from exploitation efforts, as mandated in the Ministry of Home Affairs Regulation on the Recognition and Protection of Indigenous Peoples 2014

Restorative actions

- Act immediately to minimise pollution from existing mining activities by requiring the companies to ensure sediment from deforested areas and during transportation does not enter the sea

- Immediately seek to remedy the environmental damage already caused, for example by replanting mangrove areas around Gag and Kawe islands

- Conduct an open audit and publish the results of the audit on pollution identified in this report, as mandated by the Environmental Protection and Management Law of 2009 (Article 63.1 and Article 71); the Government Regulation on Environmental Protection and Management of 2021 (Article 527.1 and Articles 567–570); and the Mineral and Coal Law of 2020 (Article 96D).

- If proven to have committed violations as revealed by the open audit, impose administrative and criminal sanctions on the nickel mining companies in Raja Ampat as stipulated in the 2009 Environmental Protection and Management Law and the 2020 Mineral and Coal Law.

Preventive and future actions

- Ensure transparency regarding any future expansion in Raja Ampat and across West Papua, including the awarding of new licences, making that data accessible to local communities, and guaranteeing that Indigenous communities are accorded Free, Prior, Informed Consent as required by international law.

- Act immediately to minimise pollution from existing mining activities by requiring the companies to ensure sediment from deforested areas and during transportation does not enter the sea

- Provide clear shipping data on the route taken by mined nickel ore to processing facilities

- Improve the supply chain transparency and traceability of the nickel industry by requiring extraction data to be provided by all private companies

- Require all financial institutions to conduct robust environmental and social due diligence before approving financing for nickel projects, in line with OECD guidelines.

To EV companies and battery manufacturers

- Demand that nickel suppliers stop sourcing nickel ore from Raja Ampat

- Fully audit mining sites in addition to the processing operations to ensure they are respecting human rights and the environment impact and supply chain audit

- Increase transparency about EV supply chains by providing public information about all companies in your supply chain engaged in mineral mining, refining, smelting, and battery production

- Use purchasing leverage to require all upstream suppliers to adhere to the OECD Due Diligence Guidance and halt sourcing from companies that fail to prevent or remediate environmental harm or human rights abuses

- Ensure that all nickel sourced from Indonesia is fully compliant with the OECD responsible minerals guidelines and UN business and human rights guidelines

- Demonstrate steps taken to verify that nickel in the supply chain is not linked to environmental degradation, human rights abuses or climate damage

To Indonesian financial institutions, banks and international investors and financiers

- In line with the UN Guiding Principles and OECD Guidelines, conduct enhanced due diligence

- Immediately suspend financing to projects that violate FPIC or have unresolved environmental or social harms, until full human rights and environmental due diligence is conducted, independent assessments are completed, and effective mitigation and remediation measures are in place

- Condition future investment on robust FPIC, EIA, and human rights standards being met

International Partners Group (IPG), including EU, US, Germany, Japan, UK, France, responsible for the JETP

- The EU and other JETP partners must ensure that no climate finance or investment frameworks under the JETP are used to support or enable nickel mining or smelting projects that are powered by coal, harm Indigenous communities, or violate environmental safeguards. All JETP-related funding should be conditional on robust FPIC, independent EIAs, and public transparency.

- The G7 countries are urged to consider Indonesia’s legislation before deciding to invest, including the fact that human rights and environmental protection regulations remain weak

To the European Commission (DG Trade)

- Condition any future trade agreement (Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA)) with Indonesia on demonstrable compliance with human rights, Indigenous land protections, and environmental safeguards in the transition minerals sector

- Include enforceable clauses on due diligence and grievance mechanisms for supply chains of critical minerals under CEPA

- Conduct open CEPA Monitoring with Indigenous peoples and civil society groups. Ensure a Human Rights Dialogue that binds the Indonesian Government to improve governance of critical mineral mining

To the Chinese government

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment and Ministry of Commerce of China should rigorously monitor and guide Chinese companies’ ESG performance overseas, to ensure that they are in line with the 2022 "Guidelines for Ecological and Environmental Protection of Overseas Investment Cooperation and Construction Projects" (‘the 2022 Guidelines’)

- Adopt law and regulations, requiring Chinese mining companies to conduct robust ESG due diligence aligned with international standards (e.g., UNGPs, OECD Guidelines) to identify, prevent, and mitigate risks of human rights abuses, environmental harm, and unethical business practices

- Require companies operating overseas to establish effective community consultation and grievance mechanisms to uphold the right of affected communities to Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC)

Read this page in