As the world’s leading owner of transition mineral production, China must shoulder the burden of keeping the energy transition green. But do its regulations of mining abroad (and the industry’s ESG issues) stand up to scrutiny?

China’s overseas mining investment hit another high last year, with a record-breaking $21.4 billion allocated under its Belt and Road Initiative (B&R) as the government continues to place emphasis on securing raw materials for the energy transition.

China owns the largest share of cobalt production in the world, accounting for 42% of production ownership, as well as the majority (40%) of its consumption. China also consumes the most lithium (59% of the world’s share). Both minerals are key materials used in electric vehicles (EVs).

But with great industry power comes great responsibility.

China has already shown its commitment to global climate governance in other areas, hoping to position itself as a proactive player through its Dual Carbon Goals. As the host country of COP15, it also advanced the implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

It is a member of the UN-convened Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals and has reaffirmed its commitment to promoting the global green energy transition, despite geopolitical challenges.

But, around the world, mining has a long history of causing environmental and social harms. The question is: do China’s regulations sufficiently address the environmental, social and governance (ESG) impacts of its overseas mining operations? Doing so will be crucial for ensuring a just transition globally.

What is the Chinese policy on transition mineral resources?

China has clear ambitions to “integrate into the global energy value chain", alongside its domestic focus on developing strategic mineral resources.

China has identified 24 minerals that are critical to the nation’s development. It encourages Chinese companies to expand overseas by actively participating in entire value chains – from exploration to processing and manufacturing – and promotes integrated investments that link minerals, energy and logistics.

But China often mines in regions where weak governance amplifies risks of environmental degradation and human rights violations.

S&P Global data shows that, as of June 2023, primary lithium projects in Latin America and Africa with links to Chinese companies have covered multiple countries with poor regulation track records, such as Bolivia, Argentina, Mali, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zimbabwe. Is China well prepared enough to face the ESG challenges in these areas?

How does China regulate mining’s environmental impacts at home and overseas?

At home, China has made significant strides in mitigating the environmental impacts of mining. Requirements for an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), consideration of the "three simultaneities" (design, construction and operation of environmental protection facilities alongside mining projects), ecological restoration of mining areas and abandoned mines, green mining, and mining safety have been actively updated and implemented by regulators.

By 2028, 90% of large-scale and 80% of medium-sized mines in production inside China must meet these green mining standards.

However, the same requirements do not necessarily apply to its mining overseas. China’s ecological redline and national land-use planning regulations, which limit or ban environmentally destructive activities in sensitive areas, are a prime example: rules are strictly enforced domestically but not abroad.

China explicitly limits its own laws’ and regulations’ impacts in foreign territories to respect other countries’ judicial sovereignty – a stance that has been observed as being applied selectively.

What is China doing to reduce transition mineral mining’s environmental impacts abroad?

Mining is big business and Chinese companies are not alone in extracting other countries’ natural resources. But there are hopeful signs of policy change in China.

Nearly a decade after launching the Going Global Strategy (1999), which was later enhanced by the Belt and Road Initiative (B&R) (2013), China’s overseas regulation started targeting private enterprises.

A 2017 Code of Conduct also mandated environmental due diligence before acquiring overseas projects. Policies began to cover Central State-owned Enterprises (CSoEs) in 2021, requiring compliance with both Chinese and local laws, but without explicitly addressing ESG considerations.

Major Chinese CSoE mining companies – including China Nonferrous Metals Mining Group (CNMC), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), China Minmetals, China National Gold Group (CNGG) and Aluminium Corporation of China – faced ESG and human rights controversies abroad. Yet supervisory actions from Beijing were rarely seen.

By contrast, a 2023 domestic crackdown during ministerial-level inspections held almost 150 officials from CNMC and CNGG accountable for environmental violations inside China.

Even amid weak enforcement, policy reforms kept accelerating. Within less than six months, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment and the Ministry of Commerce had together issued two environmental guidelines for overseas investments in July 2021 ("2021 Guidelines") and January 2022 ("2022 Guidelines").

The 2022 Guidelines were well-received by the global community for explicitly including EIA, environmental monitoring, ecological restoration, community engagement and transparency, and adherence to international rules (or China’s sometimes stricter environmental standards for production in areas with less robust local standards).

Notably, it singled out mining projects for reform, emphasising pollutant control, waste utilisation, tailing storage, groundwater and land protection, and biodiversity conservation (Article 12).

But the 2022 Guidelines may still cast doubts around the strength of regulation and corporate compliance incentives, just as the 2021 Guidelines did. Their overgeneralised and aspirational language, along with continued silence on enforcement and accountability, risk a disconnect between policy and practice.

What are the ESG challenges in mining for China’s overseas operations?

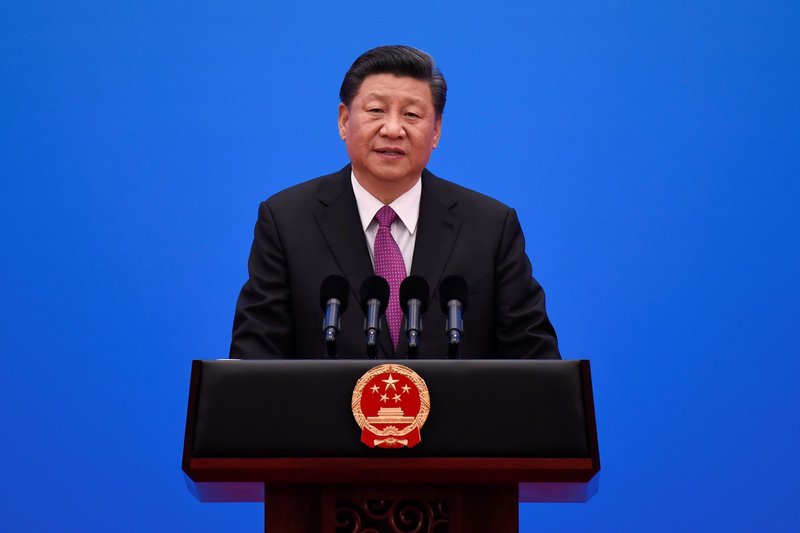

In his 2018 speech marking the fifth anniversary of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (B&R), President Xi Jinping called on Chinese companies to pay attention to environmental protections and their social responsibilities to be “ambassadors for B&R development.”

Citing Xi’s speech, seven ministries released a Due Diligence Guideline requiring companies that are engaged in foreign trade, investment and contracting projects to identify, assess and monitor compliance risks, including those associated with suppliers and contractors.

The Due Diligence Guideline touches on ESG due diligence by requiring countries to do risk assessments and explicitly integrate compliance requirements into contracts in areas such as anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism financing, labour rights, environmental protection and anti-corruption.

But the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, China’s central environmental regulator, was absent from the Due Diligence Guideline’s issuers, and the Due Diligence Guideline lacked a systematic framework for risk control and traceability – providing broad compliance guidance rather than a detailed supply chain ESG due diligence approach.

The 2022 Guidelines go further, requiring environmental due diligence before overseas mergers and acquisitions can take place, covering ecological damage, pollution, penalties, lawsuits and environmental risks.

"Green supply chain management” and “green procurement” are also mentioned, though only briefly and without clear definitions. More importantly, and worth reemphasising, the 2022 Guidelines remain non-binding – offered as a "reference" rather than “mandatory requirements”.

This lack of teeth is also reflected in sector-specific initiatives. China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters (CCCMC)’s voluntary due diligence guidelines align with international standards, particularly in the areas of risk-based due diligence, traceability and responsible sourcing.

However, the self-policing nature of CCCMC risks there being limited pressure on Chinese companies to comply, leaving room to source minerals linked to illegal mining and human rights abuses.

In summary, Chinese mining companies still have a long way to go in implementing Xi’s speech and turning their vision into reality.

Is China’s overseas mining ensuring enough transparency?

Research from 2023 suggests that, while Chinese mining companies are increasingly engaging in transnational extractives governance initiatives to enshrine transparency, Chinese regulators remain passive and reluctant to be bound by “foreign rules.” But progress in developing Chinese regulations has been slow.

The 2022 Guidelines vaguely state that "enterprises should report environmental compliance information according to relevant regulations." Yet it remains unclear what regulations govern disclosure for overseas operations, and domestic rules do not explicitly extend beyond China’s borders.

In March 2025, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) revised its Measures for Information Disclosure of Listed Companies, requiring listed companies to publish sustainability reports in line with stock exchanges rules.

The exchanges require listed companies to fully identify, assess and disclose whether activities such as procurement, production, sales and overseas investment could have significant economic, social or environmental impacts.

But disclosing pollutant discharge and its effects on workers and communities is only obligatory for companies – and key subsidiaries – appearing on government-designated lists for mandatory environmental disclosure. These lists are determined by municipal-level Ministry of Ecology and Environment offices within their local jurisdictions.

Whether these lists consider companies’ overseas environmental performance remains unclear, if not unlikely.

How much do China’s overseas operations benefit and seek consent from communities affected by mining?

This regulatory ambiguity is also reflected in Chinese companies’ unresponsiveness to community and civil society requests for information and dialogue.

Communities abroad where mining operations take place frequently report inadequate consultation in project construction and resettlement, leading to a lack of free, prior and informed consent, involuntary displacement, insufficient compensation and the loss of traditional livelihoods.

I don't mind that they dig holes on our land, I don't mind that they take our minerals, but I do mind that they don’t talk to us

Community consultation and public hearings in overseas projects are required by Chinese regulators, yet lack enforcement. Likewise, the non-regulatory CCCMC’s mediation and consultation mechanism, launched nearly two years ago, appears to have not yet accepted a single complaint, hampered as it is by limited financial, institutional and operational resources.

China does promote employment in mining operations’ host countries as well as contributions to local development. State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC)’s 2024 data shows that 85% of employees in CSoEs’ overseas branches are local, with some achieving localisation rates exceeding 90%.

Yet, in projects like the Bikita Lithium in Zimbabwe (owned by the Chinese CSoE Sinomine), representatives from communities have questioned whether these jobs provide fair wages, fair contracts and adequate protections. Local businesses struggle to access fair opportunities in subcontracting and procurement.

Real leadership requires real responsibility

Standing at the helm of the energy transition, China’s success depends, not only on securing transition minerals, but also on ensuring ethical, sustainable and responsible extraction and processing. Its policies and practices carry profound implications for the countries where its companies operate.

While there is evidence of progress, gaps in both scope and enforcement reveal an urgent need for stronger policies that ensure transparency, rigorous due diligence, meaningful community engagement, substantive local benefit, and greater accountability.

This is the second instalment in a three-part series examining China’s dominance of the transition minerals market. Read the first explainer, which looks back at how the world’s largest CO2 emitter became a global leader in producing renewable energy.