How gas companies influence EU policy and have pocketed €4 billion of taxpayers’ money

As the European Union emerges from a damaging pandemic, it is looking to rebuild. This will require fundamental decisions about what type of future Europe wants: recreate the polluting economies that existed before the outbreak, or encourage societies that are more sustainable and equal.

Given how costly the outbreak has been – in lives, in livelihoods, in government resources – significant decisions must be made soon about which path the EU should take. According to the European Council, development after the outbreak should be “green.” Both the European Parliament and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen echoed this commitment. Europe needs “to rebuild our economies differently,” the President said, “doubling down on our growth strategy by investing in the European Green Deal.”

Download the report : Pipe Down

Download ResourceGlobal Witness has drafted an interactive map detailing the gas projects the EU has subisidised, and how much projects backed by ENTSOG companies have received. It can be accessed below.

These pledges will be tested immediately. In May 2020, the Commission began consultations on changing the law that governs how the EU supports new energy infrastructure. The law – the Trans-European Networks-Energy (TEN-E) Regulation – controls how EU institutions choose which electricity and fossil fuel projects to support. These projects include the terminals and pipelines used to import and transport fossil gas – sometimes referred to as natural gas. Under the regulation, selected gas projects get fast-track approval and access to billions in public subsidies.

However, the current TEN-E Regulation has a problem: it gifts remarkable power over EU policy to an obscure cadre of gas companies called the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas, or ENTSOG. Under the law, ENTSOG companies help the EU predict how much gas Europe needs and helps the Commission decide what gas infrastructure projects to support.

This has worked out well for the companies: having regularly – and substantially – overestimated how much gas Europe will use, projects backed by ENTSOG members have received almost 90 percent of the EU’s gas infrastructure subsidies – over €4 billion. And this year, the EU is on track to spend more public money on unnecessary gas infrastructure that risks locking Europe into decades of fossil fuel consumption.

ENTSOG has told Global Witness that there is no conflict of interest, it has stopped overestimating gas demand, and it acts only as an expert while the Commission decides which gas projects to back. The full response can be read here.

Now is the time to stop this and to rebuild better. Gas demand has been stagnant for years, and following the outbreak consumption is plummeting. Even before the pandemic, the EU pledged to reduce greenhouse emissions through the 2018 Renewable Energy Directive, the 2050 Climate Neutrality Pledge, and the developing European Green Deal. As Europe restarts its economies, the EU should not waste scarce billions on fossil fuel infrastructure that is not needed and will not meet climate change goals.

Instead, the EU should prioritise infrastructure projects that support a sustainable future using renewable energy. The first step in achieving this is to amend the TEN-E Regulation, removing companies’ influence and halting funds to fossil fuel projects.

For detail on the calculations and sources included in this investigation, please download the full report (PDF, 3.76MB).

Global Witness has drafted an interactive map detailing the gas projects the EU has subisidised, and how much projects backed by ENTSOG companies have received. It can be accessed below.

COMPANIES’ CONTROL OVER EUROPE’S GAS POLICY

Europe is flooded with gas, undermining the EU’s ability to stop climate change. In 2019, member states consumed 482 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas. According a report ordered for the Commission, by 2030 this number needs to fall at least 30 percent if Europe is to meet its climate change targets.

One reason why Europe uses too much gas is because the EU has outsourced critical policy decisions to companies that profit from the fuel. These companies – called Transmission System Operators (TSOs) – run the terminals that bring gas in, the tanks that store it, and the pipelines that push it across Europe. There is a company for most EU countries, like Snam in Italy, Enagás in Spain, and GAZ-SYSTEM in Poland. Few of these companies are household names internationally, but their influence can be far-reaching. Belgium’s Fluxys also owns infrastructure in Germany, France, and Greece, while the UK’s National Grid runs electricity and gas networks in both Britain and the US.

Gas is not the answer

In recent years, fossil gas has been the world’s fastest growing fossil fuel. In 2019, European carbon dioxide emissions from gas were projected to be higher than from coal. Emissions are also rising, with gas accounting for over 50 percent of the increase in global carbon emissions since 2016. Matters may be even worse, as the production and transport of gas results in the leakage of large quantities of methane – another powerful climate change driver.

However, Global Witness’ 2019 report Overexposed showed that all production from new oil and gas fields – beyond those already in production or development – is incompatible with the Paris Agreement goal of keeping warming under 1.5°C. Achieving this target requires gas production to drop by 40 percent worldwide over the next decade. Ultimately, greenhouse gas emissions from the extraction, transport, and combustion of gas mean that it is fundamentally incompatible with the EU’s efforts – and pledges – to fight climate change.

This reality has caused ENTSOG to switch tack. Seeking to justify the projects from which its members profit, the organisation now argues gas infrastructure can be converted to transport “decarbonised” gas. With the right investment, ENTSOG argues, its processing stations and pipelines could transport hydrogen derived from fossil gas, with carbon dioxide captured and stored before it reaches the atmosphere, among other options.

These new arguments, however, have a problem: many of the technologies, including fossil gas- derived hydrogen and carbon capture, are unproven and expensive. Some also require, and could be used to justify, significant upgrades to Europe’s gas infrastructure, which would benefit ENTSOG companies.

These false promises further demonstrate the need to remove ENTSOG’s power over European policy. If the EU is to seek alternative – carbon-free – energy sources, it cannot continue to be influenced by gas companies promoting risky options from which they would profit.

Read more here on why gas isn't the answer to the climate crisis.

In 2009, seeking more coordination between national-level companies, the EU enacted the European Gas Regulation, ordering TSOs to join a network it created called ENTSOG. ENTSOG currently has 44 member companies from 24 European countries – with some states like Germany and Spain represented by more than one company. Despite this quasi-governmental function, ENTSOG also has the appearance of lobbying outfit. It is registered as a trade association with the EU’s lobbying database and shares membership – and a Brussels office – with the major gas lobbying trade group, Gas Infrastructure Europe (GIE).

In April 2020, ENTSOG even joined other lobbying groups signing a letter that told the EU to use COVID-19 stimulus funds to pay for new “decarbonised” gas infrastructure.

ENTSOG’s member companies have been gifted significant power over Europe’s gas policy. In 2013, the EU passed the Trans-European Networks-Energy (TEN-E) Regulation with the aim of improving inter-state connections, mitigating supply disruptions from countries like Russia, increasing competitiveness, and promoting sustainability. The regulation set to do this by creating a category of gas, electricity, and oil projects to which the EU gives preference – Projects of Common Interest (PCI).

Projects that become PCIs have an increased chance of being built. The TEN-E regulation says they should be “allocated the status of the highest national significance possible and be treated as such in permit granting processes,” and are assigned government coordinators to ensure quick decisions. PCIs also get access to subsidies from different EU institutions, including the dedicated Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) fund. Since 2013, the Commission has a produced list of PCIs every two years, approving hundreds of projects such as electricity grids connecting France and Spain and gas pipelines between Poland and Slovakia.

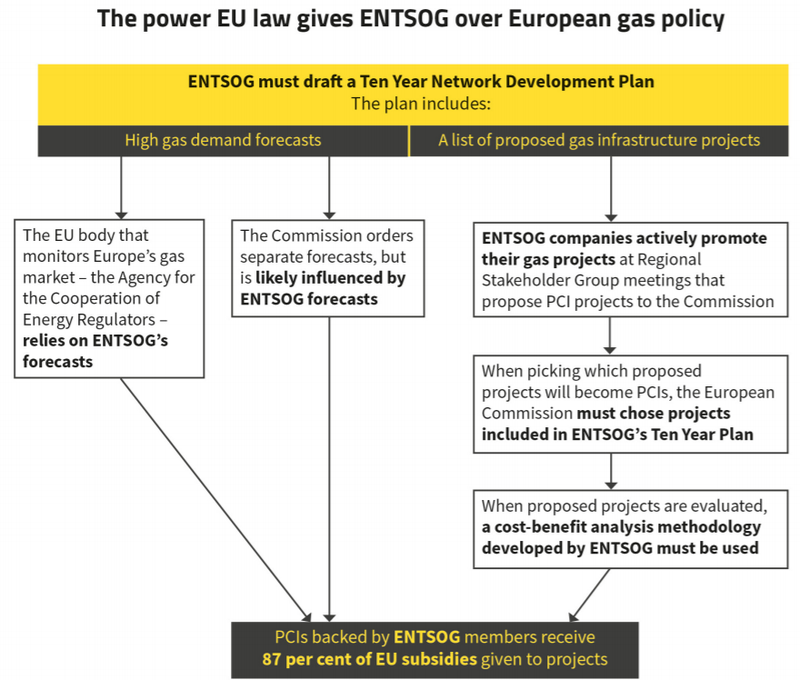

ENTSOG has considerable influence over how the Commission choses PCIs. Every two years, ENTSOG produces a long-term gas infrastructure plan called a Ten Year Network Development Plan (TYNDP). These plans contain ENTSOG’s estimates of how much gas Europe will consume in the coming years and a list of infrastructure projects that ENTSOG wants built.

Under the TEN-E Regulation, the Commission’s choice of what PCIs it wants to build is limited to those contained in ENTSOG’s TYNDP. The Commission does not directly rely on ENTSOG’s demand predictions, but in endorsing TYNDP projects the Commission indirectly relies on ENTSOG’s demand estimates upon which they are based. And the EU body that monitors Europe’s gas market – the Agency for the Cooperation of Energy Regulators (ACER) – does rely directly upon TYNDP demand forecasts when making its estimates. As such, it is likely that ENTSOG’s predictions also carry considerable weight when the Commission is estimating how much gas Europe will consume.

ENTSOG members are also part of the process of deciding which projects are put forward to be PCIs. To be considered by the Commission, a PCI is proposed first by a gas company and then by a stakeholder group located in the region where the project would be built. These groups hold multiple meetings to determine which projects to propose and are mandated to include ENTSOG members. In 2017, Friends of the Earth Europe reviewed the influence ENTSOG companies had over these meetings, documenting how companies were “key players” actively promoting projects they wanted to build.

ENTSOG also helps design the process by which PCIs are evaluated. The methodology by which each project is assessed – the cost-benefit analysis – is developed by ENTSOG, not the Commission itself. ACER has criticised ENTSOG’s most recent methodology because it may overestimate the benefits of proposed gas projects.

The fact that gas companies have institutionalised influence over how much gas Europe thinks it needs and the infrastructure it should build represents a clear conflict of interest. Writing to Global Witness in June 2020, ENTSOG denied there is a conflict – its full response can be read here. ENTSOG said it is in a “unique position” to provide gas demand forecasts, but these were not produced to help assess proposed new gas projects. It does develop the cost-benefit analysis by which projects are evaluated, but this methodology is – as above – reviewed by ACER and approved by the Commission. It is the Commission, European states, and states’ gas regulators that approve PCIs, not ENTSOG.

And, the trade body argues, ENTSOG does not submit gas projects to the Commission for PCI status – gas companies do. Of course, it should be noted that ENTSOG is a collection of the gas companies that submit projects to the Commission.

The evidence shows that the TEN-E Regulation has largely delegated decision making on gas projects to companies that financially benefit from those projects. The results, as shown in the next section, are both environmentally and fiscally harmful for EU citizens.

COMPANIES’ DAMAGING OVERINFLATED GAS FORECASTS

Evidence collected by Global Witness suggests that the power ENTSOG enjoys over EU gas policy will lead to wasteful and damaging decisions that Europe cannot afford as it seeks to rebuild sustainable economies.

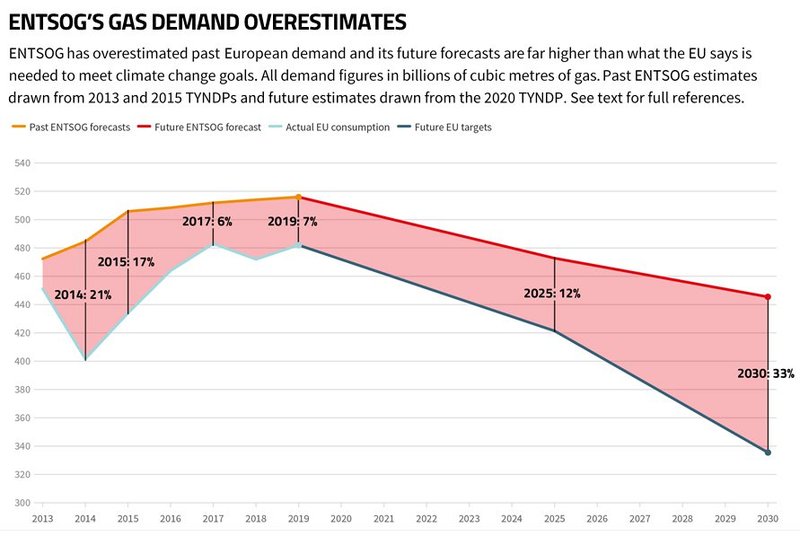

Over the past decade, ENTSOG has regularly overestimated how much gas Europe would consume – forecasts that have led to the building of unnecessary infrastructure. In 2015, the organisation’s TYNDP outlined two forecast models in which Europe did, or did not, impose carbon taxes to meet climate change goals. In the case where gas was taxed, ENTSOG actually predicted greater demand – far greater than the reality. Between 2015 to 2019, ENTSOG’s estimates were between six and 17 percent higher than actual demand, when compared to the Commission’s official figures.

This was part of a pattern. In 2013, ENTSOG’s estimates for the 2013 to 2019 period were between five and 21 percent higher than actual demand, when compared to figures from the Commission and BP. And, as reported by the think tank E3G, ENTSOG’s 2009 forecasts were high by 22 percent between 2010 and 2013.

For detail on these calculations and sources used, download Global Witness’ report.

Download the report : Pipe Down

Download Resource

ENTSOG says its forecasts are improving and it does appear to have made an effort to correct course, at least temporarily. In 2017, ENTSOG’s TYNDP estimated that demand for the year would be would be 10 percent lower than it actually was. That year’s estimates did not, however, include forecasts for 2018 or 2019. Writing to Global Witness, ENTSOG stated that its 2018 forecasts were also lower than demand, although no estimates for 2018 or 2019 appear in that TYNDP. As discussed below, ENTSOG’s recent forecasts to 2030 are much higher than the EU has estimated Europe can consume if it is to meet its climate goals.

In line with ENTSOG’s overestimates, the Commission has also developed a record of assuming Europe would use more gas than it actually does. While the Commission draws its estimates from an independent contractor and other outfits have also overestimated gas consumption, because ENTSOG holds particular power over the EU’s future infrastructure choices its incorrect forecasts should be considered particularly damaging.

ENTSOG’s overestimates harm EU policy in two ways. First, if the Commission believes Europe will use more gas then it will support – and potentially subsidise – expensive, unnecessary projects that risk locking Europe into gas consumption for decades.

According to the European Court of Auditors, this has already happened along the Baltic coast, where a gas import terminal received PCI status even though existing infrastructure was sufficient to meet decreasing gas consumption. The terminal is an example, argue the Auditors, of what can happen when the Commission has bad data, leading “to projects being financed across the EU that are not necessary to meet anticipated energy demand, or which have limited potential to provide security of energy supply benefits.”

There is evidence that the problem is more widespread. In 2019, the Commission published its most recent list of PCI projects. The list – the fourth since 2013 – garnered protests from MEPs and civil society groups that the new gas projects were unnecessary.

Indeed, a recent analysis by the data modelling consultancy Artelys shows that all of the new gas PCIs were surplus to requirement: existing pipelines and terminals are enough to meet demand through at least 2030. This is the case in both the scenario where Europe consumes more, as predicted by ENTSOG, or less because the EU is meeting its climate change goals. Current infrastructure is even sufficient to weather gas supply disruptions from Russia or North Africa – an oft-used justification for why new pipelines should be built.

According to ENTSOG, Artelys’ findings “should be considered in the context of this study alone.”

If gas projects on the Fourth PCI List are to be completed, they will require a total investment amounting to €29 billion – enough to cover the Netherlands’ flood defence budget for 26 years. In October 2020, the Commission will allocate an additional €980 million to PCIs from the Connecting Europe Facility. It is not known how much of this money will go to gas projects, as some will be allocated to electricity or transportation PCIs. However, to date approximately half of CEF funds awarded to PCIs have gone to gas projects. It is clear, however, any additional EU funds spent on gas PCIs in future years would be wasted on unnecessary projects.

Second, if Europe’s future gas plans rely on ENTSOG estimates then the EU will fail to meet its climate change goals. In December 2018, the EU enacted a Renewable Energy Directive designed to help Europe meet its obligations under the 2015 Paris Agreement, requiring that 32 percent of European energy be drawn from renewable sources by 2030. According to estimates produced on behalf of the Commission, this will require EU gas consumption to reduce from 482 bcm of gas in 2019 to 421 bcm in 2025 and 336 bcm in 2030. And future consumption may need to be lower still if new gas consumption targets are established in the proposed European Green Deal.

In 2019, ENTSOG also produced multiple estimates for how much gas it thought Europe would use. The higher of these forecasts – which ENTSOG stated was compatible with Paris Agreement targets – predicted the EU could consume 473 bcm in 2025, while in 2030 the EU could consume 445 bcm. Otherwise put, ENTSOG estimates that – in 2030 – Europe will use a third more gas than the EU thinks is possible if it is to meet necessary climate targets.

The EU will need to be ambitious in cutting gas consumption if it is to meet targets under the Paris Agreement, Renewable Energy Directive, Climate Neutrality Pledge, and – likely – the Green Deal. However, if the EU continues to follow ENTSOG’s overly-high gas consumption forecasts it will be encouraged to continue supporting unnecessary infrastructure projects it believes are needed to carry the gas. Given that gas import terminals and pipelines operate for decades, the repercussions of these bad investments could be long-lasting, with Europeans either paying for infrastructure they do not use, or locked into consuming fossil fuels that will overheat the planet.

ENTSOG companies like Fluxys are members of a coalition building the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, which has received almost €1 billion in EU subsidies. Konstantinos Tsakalidis/Bloomberg via Getty Images

COMPANIES’ €4 BILLION SUBSIDY WINDFALL

ENTSOG’s influence over the Commission not only risks bad EU decisions, it has also resulted in a windfall for the companies at the heart of this process: €4.049 billion in taxpayer subsidised finance, according to European Union data.

Under the TEN-E Regulation, any company can propose a PCI and any company can apply for a subsidy. In practice, however, the control ENTSOG members have over the PCI process has allowed them to benefit most from taxpayers’ money. Since 2013, €4.662 billion in subsidised grants and loans has been provided to gas PCI projects. An overwhelming 87 percent of this money has gone to projects backed by ENTSOG members. In some cases, ENTSOG members have received all of this finance alone, while in other cases they have received it as members of a coalition backing a project.

The largest source of grants for PCI projects is the CEF, created so “tailor-made support can be provided to those projects of common interest which are not viable under the existing regulatory framework and market conditions.” Since 2013, gas PCIs have received a total of €1.514 billion in CEF grants. Over €1.137 – 75 percent of these funds – have gone to projects backed by ENTSOG companies, including Poland’s GAZ-SYSTEM and Lithuania’s Amber Grid that are building a pipeline connecting the two countries.

In addition to CEF grants, the EU has also provided PCIs grants through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). The ERDF promotes projects in less wealthy parts of the EU, and since 2013 has provided gas PCIs with €607 million in grants. A full 100 percent of these funds went to PCI projects backed by ENTSOG members. These have included a gas pipeline between Greece and Bulgaria, to which ERDF contributed over €33 million in 2014.

And PCI projects have received subsidised loans from the EU’s “hidden giant,” the European Investment Bank (EIB). Owned by EU member states and able to provide long-term credit cheaper than private banks, the EIB has financed €2.540 billion worth of gas PCI projects since 2013. In 2019, the EIB announced it would no longer fund fossil fuel projects, but created a special loophole that will allow it to continue awarding loans to PCIs until the end of 2021.

The large bulk of EIB’s PCI financing – €2.305 billion, or 91 percent of the total – has gone to projects tied to ENTSOG members. But even within ENTSOG’s membership, one company has dominated. Since 2014, the Italian gas giant Snam and its partners have received €1.527 billion in loans to build infrastructure in Italy and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) bringing Azerbaijani gas to Europe.

In its response to Global Witness, ENTSOG stated: “ENTSOG does not back any PCI projects. Indeed, some project promoters who submit their projects to the TYNDP process are members of ENTSOG, given that gas pipelines are the biggest part of the EU gas infrastructure, operated by ENTSOG members, in a regulated activity overseen by National Regulation Agencies.”

This page contains an interactive map that shows what the EU’s subsidies have been spent on and provides sources for these subsidies. A list of EU subsidies and sources can also be downloaded here.

The size of the subsidies provided to ENTSOG members demonstrates the need to remove their power over EU decision making processes. That companies are able to influence how the Commission picks gas projects to support and then receive billions to build these projects represents an unacceptable conflict of interest. That subsides these companies receive are paid for by public grants and finance raises questions about how these European institutions spend taxpayer money.

RECOMMENDATIONS

As Europe decides how to rebuild following the debilitating COVID-19 outbreak, scarce taxpayer funds should not be spent on unnecessary gas projects that threaten the EU’s climate goals. To prevent this from happening, however, the EU should end the institutionalised influence gas companies – through ENTSOG – have over gas policy.

This is possible now. In May, the Commission began a consultation on what changes should be made to the TEN-E Regulations, and in it is anticipated the European Commission will propose a revised regulation to the European Parliament and Council by the end of 2020.

The Commission, and ultimately its co-legislators, should amend the TEN-E Regulation to remove ENTSOG’s policy making influence. This should include:

- ENTSOG’s forecasting and infrastructure development responsibilities should be transferred to an independent, expert, public body free from corporate interests, which think tank E3G has referred as a “Clean Economy Observatory.” This body would identify consistent assumptions to inform planners about infrastructure decisions, present a range of energy strategies, and make recommendations about which strategies are best.

- ENTSOG members should be prohibited from participating in regional stakeholder meetings that develop proposed PCI lists.

- The responsibility for producing the methodology for cost-benefit analyses by which PCIs are assessed should be transferred from ENTSOG to the Commission, drawing upon advice provided by the Clean Economy Observatory.

The amended TEN-E Regulation should also be aligned with the EU Green Deal and the Climate Neutrality Pledge. This should include:

- Ensuring that all fossil fuel projects are excluded from future Project of Common Interest lists, including those for its permutations like hydrogen from fossil gas. These projects should also be excluded from direct or indirect subsidies from the Connecting Europe Facility, European Regional Development Fund, and other funds.

- Ensuring future infrastructure plans prioritise renewable energy systems and building more energy efficient infrastructure.

Changing the TEN-E Regulation will not, however, prevent anticipated awards of subsidies to PCI projects in 2020. These subsidies should also be halted, including:

- The Commission should cease issuing funds from the Connecting Europe Facility to gas PCIs, including those contained in the Fourth PCI List.

- The European Investment Bank should cease financing gas PCIs, including those contained in the Fourth PCI List.

The Commission should also start consultations in order to amend the 2009 Gas Regulation, removing ENTSOG’s mandate to produce Ten Year Network Development Plans that include its demand forecasts and infrastructure project lists.