How SOCO dumped Congo oil block in contentious Africa exit

Publicly listed SOCO International Plc disposed of one of its last Sub-Saharan Africa assets in a deal that breaches Congolese law and appears to make no commercial sense, our new investigation reveals.

For the second time in less than a decade, the small central African petrostate Republic of Congo is on the brink of bankruptcy.

Congo is Sub-Saharan Africa’s third largest oil producer, yet the revenues of this lucrative but finite resource do not appear to be making it into the state coffers.

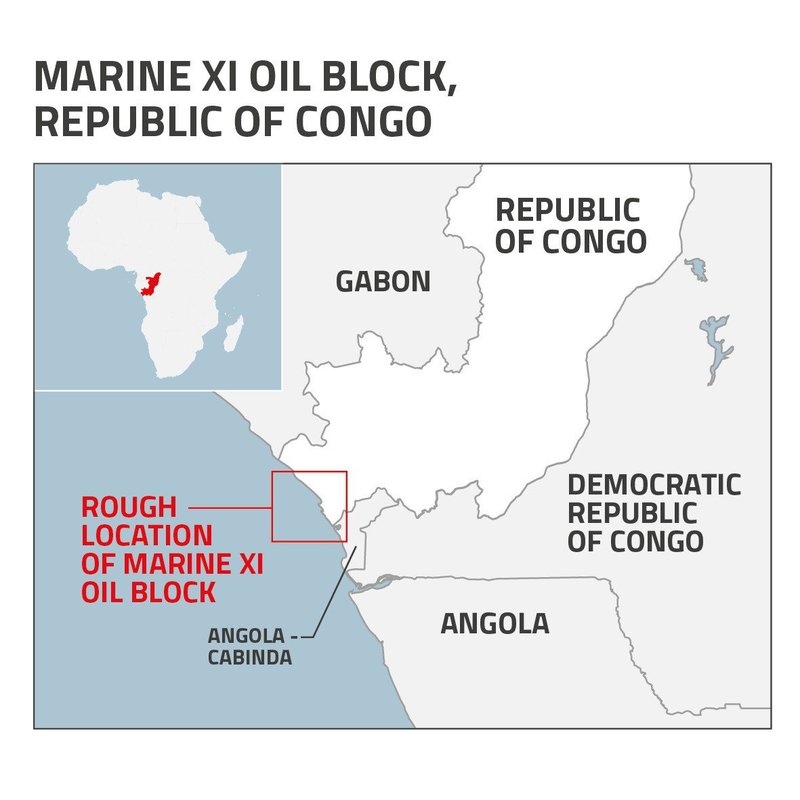

Amidst this context, Global Witness scrutinised a deal over one of the country’s prime untapped offshore oil blocks, Marine XI. From London to Geneva, Congo to tropical archipelagos, we pieced together leaked documents, testimony and expert opinion to unpack what can only be termed as a dud deal – for Congo, and for London-listed oil company SOCO International’s shareholders, which include major pension providers.

SOCO’s exit marks end of a controversial history

The deal, which took place in June 2018, marks SOCO’s departure from Sub-Saharan Africa. The company’s history there has been mired in controversy.

From 2007 to 2015, it attempted to explore for oil in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo’s Virunga National Park, a UNESCO-protected World Heritage Site, paying others who bullied or bribed anyone who got in its way.

Nonsensical deal leaves Congo block with uncertain future

SOCO EPC's office in Pointe-Noire, Republic of Congo

SOCO left Republic of Congo in a manner true to form. It sold its operating stake in Marine XI to an opaque shell company with no prior experience, cash or assets. That company promptly installed a close relative of the incumbent president, otherwise known as a ‘politically-exposed person’ (PEP), to manage its local business and started to transfer payments to at least one company connected to its CEO.

SOCO failed to inform or seek authorisation from Congo’s oil authorities prior to the sale, in breach of Congolese law.

SOCO’s deal does not appear to make commercial sense. It announced completion of the transaction without receiving any money and had at least one better offer, which it declined. Payment for the asset was conditional on certain terms, which ran an eighty to ninety-eight per cent chance of failure, the company reported shortly after the deal.

Overnight, the Congolese government found an empty shell company in control of one of its oil blocks and SOCO’s shareholders found themselves an asset short with nothing concrete to show for it.

Corruption signs

This is a story of cowboy capitalism among a tight network of industry insiders, which takes place against the backdrop of a country yet again seeking bailouts from foreign creditors.

For over two decades, Global Witness has investigated corruption in deals for natural resources. On first inspection, this one has many of the tell-tale signs, which require further scrutiny: a seemingly nonsensical deal; the absence of a competitive sale process; questionable payments to related companies; the use of anonymous companies registered in secrecy jurisdictions, which disguise their real beneficiaries; and the involvement of PEPs.

The Congolese oil authorities have begun to investigate; it is time UK regulators did the same.

Read this page in