In memory

This report is dedicated to all those individuals, communities and organisations bravely speaking out or taking action to defend their rights to land and a clean, healthy and sustainable environment.

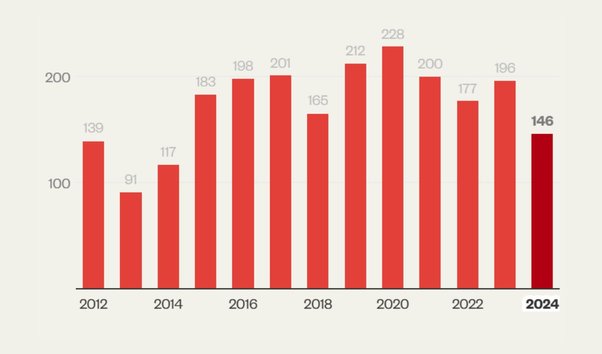

Last year, 146 people were murdered or disappeared for doing this work.

We acknowledge that the names of many defenders who were killed or disappeared last year may be missing and we may never know how many more gave their lives to protect our planet. We honour their work too.

Foreword

Selma dos Santos Dealdina Mbaye is a Quilombola activist and Political Coordinator at the Coordenação Nacional de Articulação das Comunidades Negras Rurais Quilombolas (CONAQ), an organisation fighting for the ancestral land rights of Afro-descendant communities in Brazil.

Here she talks about what land and environmental protection means to her community – and to communities like theirs across the world – and the dangers they face defending it.

Selma dos Santos Dealdina Mbaye is a Quilombola activist and Political Coordinator with CONAQ – a Quilombola organisation fighting for the ancestral land rights of Afro-descendant communities in Brazil. Fernanda Frazão / Global Witness

“What is land? To me and my community, as Quilombolas, land is not merely soil that we stand on. To us, and to so many communities worldwide, it is the very essence of who we are.

"Our ancestors were first kidnapped from Africa around 500 years ago. They were shipped across the Atlantic to the Americas, where they were forced to work as slaves on large sugarcane plantations on lands over which they had no rights. Those who managed to escape established the first land settlements – or quilombos.

Land is our home, our culture and our source of life. Our fundamental struggles have always revolved around land

"Their story is one of resistance and the pursuit of justice. It’s a struggle we Quilombolas continue to share with so many other communities worldwide demanding their rights to land and to a sustainable environment.

"Yet they – like us – are fiercely attacked for doing so.

"My organisation, CONAQ, has been persistently demanding our rights over land for the best part of three decades. As our saying goes, 'Titled land means granted freedom'. But it doesn’t just benefit us; Quilombos play a significant role in forest protection, and our communities have successfully maintained a wide range of ecosystems for generations.

"When we, and other Afro-descendant, Indigenous and campesino communities make decisions about our lands, we manage natural resources and wildlife respectfully and sustainably.

Members of the Quilombola community of Pedras Negras fish in the Guapore river in Brazil. Traditional practices of Indigenous, Afro-descendant and campesino communities often go hand in hand with land and environmental protection. Lalo de Almeida / Panos

"With closer ties to the lands we live on, our traditional practices result in a more sustainable world. By granting us land rights, our planet is better off.

"But we need more than land rights. Too often we are subject to unspeakable violence. At least 413 land and environmental defenders have been killed or disappeared in Brazil since 2012 – 36 of whom were Afro-descendants, according to Global Witness’s data.

"We are still reeling from the killing of our beloved leader Mãe Bernadete in 2023, six years after the murder of her son. We know that before she died, Mãe denounced several threats of violence towards her and her community.

"Mãe’s role as a land and environmental defender undoubtedly made her a target for attack. But along with other Afro-descendant community members in need of collective protection, her race made her even more vulnerable to violent attacks.

"A state protection programme was meant to keep her safe, but it failed to prevent her murder. Too many other defenders have also been let down by protection programmes like these. In Chapter Four, you can read about peasant leader Jani Silva and her life in a flawed protection programme in Colombia.

Protester holding the placard, "Who gave the order to kill Mãe Bernardete Pacifico", a Brazilian Quilombola defender killed in 2023. Alamy, Wagner Vilas / Zuma Press Wire

"Indigenous communities across the world are disproportionately targeted, with attacks on their leaders casting a devasting ripple effect across their communities. The case of Indigenous Mapuche leader Julia Chuñil – featured in Chapter Three – is a chilling example. She disappeared in 2024, after spending years working to secure the ancestral rights of her community in Chile.

"The threats our communities face are sustained by weak state protection measures, the weaponisation of laws against us, and high levels of impunity – so defenders like Julia receive little to no justice.

"Elsewhere, entire communities protecting some of the world’s climate-critical ecosystems – from oceans to rainforests – are under threat. For example, extractive industries are putting the forests of the Ekuri community in Nigeria under renewed pressure, as you can read in Chapter Two.

"This is a familiar story for forest defenders the world over – from Africa to tropical rainforests in Asia to South America’s Gran Chaco, Pantanal, Amazon and my home: the Cerrado.

Defender Lawrencia Agbor is a strong advocate for forest protection, emphasising the vital benefits the local community derives from it, including food, medicine and clean air. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

"Yet no matter where in the world we are, defenders share the same goal: to prevent the underlying drivers of harm to our communities. This often means shifting the balance of power away from profit-seeking governments, big business and illicit actors – whose activities harm people, land and the environment – and towards the communities who live on and protect that land.

"Things can change through sustained and collective action. In November 2025, state officials, business representatives and global civil society will gather in Pará in the Brazilian Amazon for COP30 – a symbolic place for Quilombolas. It was in Pará that Quilombola land was recognised for the first time by the Brazilian government 30 years ago.

"We will be there to champion the rights of those on the front lines of the climate crisis – defenders and their communities – and ensure our voices are heard.

"It’s clear that our knowledge, experience and practices as defenders must be at the heart of the solutions to the crisis. But we cannot continue to protect the planet – including its biodiversity and its forests – if world leaders do not protect us from attack.

"Now is the time to put an end to the cycle of violence once and for all."

Roots of resistance

Funeral of murdered Mexican defender Marcelo Pérez, a priest working to protect land rights. Luis Enrique Aguilar / Getty Images

Global findings

In 2024, 146 land and environmental defenders around the world were murdered or disappeared. The consequences are devastating – tearing apart families, upending whole communities and undermining wider human rights efforts.

They were all attacked after speaking out or taking action to defend their right to land and a clean, healthy and sustainable environment. Many were opposing harmful extractive projects, like mining, logging or agribusiness. Others were challenging systemic problems, like land inequality, environmental destruction and organised crime.

Our data helps to reveal the drivers behind reprisals against defenders and their communities and highlights the increased risks they face. Exposing these trends is the first step to protecting them and making sure they can exercise their rights without fearing for their lives.

Relatives and friends carry the coffin at the funeral of environmental activist Marco Antonio Suastegui, who opposed the construction of a hydroelectric dam in the southern Mexican state of Guerrero. Francisco Robles / AFP via Getty

Global breakdown: 2024 in numbers

Global Witness documented 146 killings and long-term disappearances of land and environmental defenders in 2024. We know that many attacks go unreported, so this figure is likely to be an underestimate.

On average, around three people were killed or disappeared each week throughout 2024. This brings the total figure to 2,253 since we started reporting on attacks in 2012. This appalling statistic illustrates the persistent nature of violence against defenders.

At least 146 defenders were killed or disappeared in 2024

Killings took many forms last year, including murder, extrajudicial execution and deaths in detention – with 142 lethal attacks. There were four documented long-term disappearances in 2024, where the defender has been missing for a period of more than six months. These occurred in the Philippines, Mexico, Honduras and Chile.

This year’s global figures are lower overall compared to 2023 – down from 196 to 146. This does not indicate that the situation for defenders is improving.

Year-to-year fluctuations in the overall number of killings and disappearances are not always representative of trends in violence at country level. Underreporting remains an issue globally, particularly across Asia and Africa. Obstacles to verify suspected violations also present a problem, particularly documenting cases in active conflict zones.

Moreover, restrictions on civic space coincides with a heightened fear among communities of speaking out against those causing damage to land or the environment.

People gather and place flowers on cardboard boxes symbolising coffins during a demonstration against the assassinations of social leaders and piece signatories in Colombia. Sebastian Barros / Long Visual Press / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

In numbers: Attacks against defenders since 2012

Explore our full dataset to find out where killings of defenders are occurring, which industries are responsible, and how this violence has changed over time

Enforced and involuntary disappearances of defenders

Alongside lethal attacks, many defenders are victims of enforced or involuntary disappearance – a unique human rights violation where people are purposefully made to vanish.

Disappearances have a doubly traumatising impact: on the victims, who face violence and torture, and are often kept fearing for their lives; and on their families who remain ignorant of their fate. Some disappeared persons are returned alive while others remain missing or are later killed by their abductors.

Not knowing whether the person is alive or dead, the families, colleagues and communities of disappeared defenders are placed in excruciating limbo. Often, they are forced to search for the disappeared person – with many facing retaliation themselves as a result.

The United Nations International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance defines an enforced and involuntary disappearance as “the arrest, detention, abduction” or other “deprivation of liberty” by “agents of the state or by individuals or groups acting with the authorisation, support or acquiescence of the state, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, which place such a person outside the protection of the law.”

Non-state actors around the world are also involved in disappearances – particularly individuals or groups suspected of links to organised crime or those operating in a wider context of armed conflicts and violence.

Global Witness documents disappearances of defenders where the individual has been missing for six months or more.

Beyond these attacks, other forms of reprisal against people taking a stand persist. Threats, harassment, criminalisation and sexual violence have marred the lives of many defenders. Often, these non-lethal attacks are a precursor to more serious violence, whether escalating over decades or rapidly in a short period of time.

The impacts on wellbeing are less visible but run deep. Anxiety, panic attacks, suicidal thoughts or depression are all common among defenders living in fear for their lives.

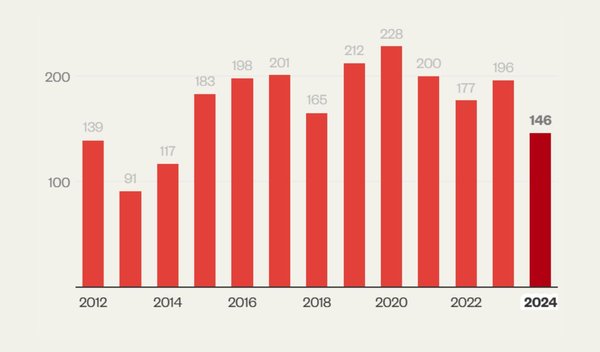

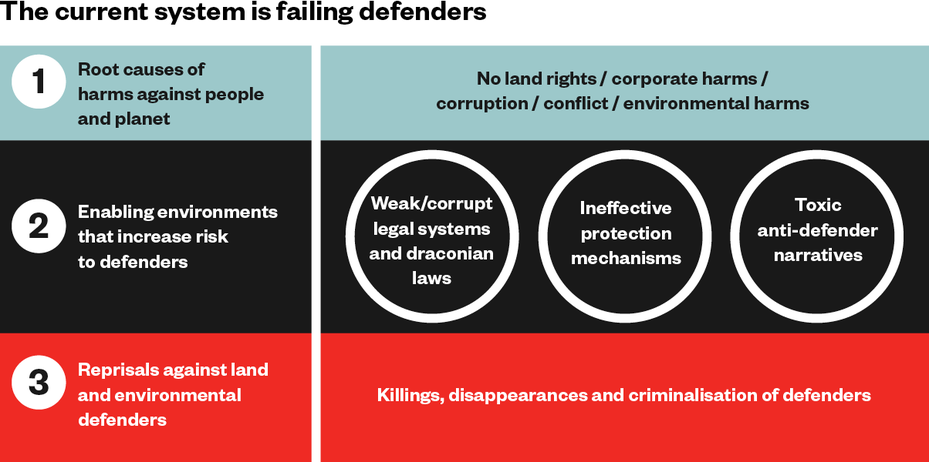

Attacks against defenders appear more common in environments particularly hostile towards activism. Of the 22 countries where Global Witness documented killings and disappearances last year, over half were categorised as "repressed" or "closed" by civic freedom tracker CIVICUS Monitor – restricting defenders’ freedom of association, peaceful assembly and expression.

The five countries where we documented the highest number of killings and disappearances in 2024 are all classed as “repressed” except for Brazil, which is classified as “obstructed”.

Hundreds of mourners attend the funeral of the Catholic priest and Mexican land and environmental defender Marcelo Pérez in 2024. Luis Enrique Aguilar / AFP via Getty Images

Where: Regions and countries

A total of 82% of all the cases we documented in 2024 took place in Latin America, where we have recorded the highest proportion of cases every year for over a decade. This violence continues to severely hamper the lives of defenders.

The majority of killings and disappearances in 2024 occurred in Latin America

Indigenous Peoples and small-scale farmers are the worst affected, with 45 defenders killed or disappeared in each of these categories in 2024.

In Africa, we recorded nine killings in 2024 (6% of the total), while 16 killings (11%) took place in Asia. Accessing information continues to pose a big challenge for us in both these regions. Our documented figures do not necessarily indicate that violence is less prevalent here.

Colombia

Colombia remains one of the world’s deadliest countries for land and environmental defenders, with a third of all lethal attacks globally documented happening here in 2024. We recorded 48 killings across the country – a drop from 79 cases in 2023.

Colombian human rights organisation Programa Somos Defensores also reported a decline in reprisals against defenders – but warned that this does not equate to an overall decrease in violence.

Colombia remains the deadliest country for defenders

Since the 2016 Peace Agreement, a weak state presence in regions formerly controlled by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) has been exploited by organised crime and armed groups seeking to finance their operations through illegal economies.

Activities ranging from drug trafficking to illegal mining affect areas rich in biodiversity such as Cauca, Nariño and Putumayo.

Many of the Indigenous Peoples, peasant communities and Afro-descendants living in Colombia fear denouncing the environmental damage inflicted by extractive industries, especially those defenders operating in proximity to armed groups and within conflict zones.

Forced displacement and fear of violence enables a culture of silence, further weakening land, environmental and Indigenous movements.

Indigenous leaders attend an assembly following the murder of the Indigenous Nasa defender, Carmelina Yule Pavi. Nineteen of the Colombian defenders killed in 2024 were from Indigenous communities. Joaquin Sarmiento / AFP via Getty Images

Disputes over land continue to fuel violence in Colombia: 20 of those murdered in 2024 were small-scale farmers. Nineteen of the defenders killed were from Indigenous communities, including 13 members of the Nasa community in the Cauca region.

At least six of these Nasa defenders were Indigenous guards or part of Indigenous authorities designed to protect their territory and protect land rights.

A mix of coca cultivation, drug trafficking and armed struggle has devastated Cauca, with defenders and communities often caught in the wider conflict and facing increased dangers.

UN human rights organisation OHCHR-Colombia has expressed concern over the killings of Indigenous People in Cauca in particular, committed by non-state armed groups vying for greater control over the territories.

Recent research has also found that underreporting is a reality in Colombia, often stemming from a fear of denouncing attacks, so the number of reprisals documented is likely to be lower than the number of attacks actually experienced by defenders and their communities. With effective protection often lacking, defenders remain highly vulnerable to violence.

In Medellín, demonstrators gather to hold photos of social leaders and piece signatories assassinated in Colombia. Juan Jose Patino / Long Visual Press / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Mexico

Reprisals continued in Mexico, where we documented 19 cases in 2024 – 18 killings and one disappearance.

According to data gathered by Mexican organisation Centro Mexicano de Derecho Ambiental (CEMDA), 2024 was the second most lethal year of the past decade. It reported that defenders were also subjected to intimidation, harassment, stigmatisation, defamation – and the growing problem of criminalisation.

Nine killings occurred in the border region of Chiapas. Territorial disputes between armed groups and organised crime syndicates are reported to have increased since 2021, as they seek to control the area’s rich natural resources.

Defenders protecting access to land have been caught in the struggle after challenging the attempts of illegal groups to control access to these resources.

In 2024, seven family members were massacred after denouncing the presence of organised crime and challenging attempts to control mining operations in the region.

Brazil

In Brazil, we documented 12 killings in 2024. This represents a decrease in cases compared to 2023, when 25 defenders were killed, but non-lethal attacks remain rife across the country. Half of all those killed last year were small-scale farmers. Four Indigenous Peoples were murdered, as well as one Afro-descendant defender.

Brazilian organisation Comissão Pastoral da Terra (CPT) also reported a lower number of murders, but an increase in death threats, intimidation and murder attempts. CPT registered a total of 481 cases of attempted murder, 44% of which were against Indigenous Peoples and over 27% against Quilombolas.

A photograph depicts the moment environmental activist Phuon Keoraksmey is transported to prison to serve a 14 month sentence after campaigning against destructive infrastructure projects and alleged corruption in Cambodia. Pascal Maitre / Panos

The Philippines

Once again, the Philippines had the highest number of murders and long-term disappearances in Asia, with eight cases in 2024 – despite seeing a decrease in cases since 2023. At least six of these attacks were linked to government bodies, notably the armed forces in four cases.

But violent attacks against land and environmental defenders – and killings and disappearances of human rights defenders more broadly – have not necessarily abated.

Media and civil society reports have documented attacks against peasant communities, most notably in the Masbate, Northern Samar, Negros Occidental and Sultan Kudarat regions of the country – where there is conflict over land and natural resources.

Filipino human rights alliance Karapatan documented 14 killings of human rights defenders in 2024.

Defenders in the Philippines continue to face repression, including abduction and criminalisation – often through the tactic of red-tagging, where they are falsely accused of being communist or terrorists. Recent research has also exposed state-sponsored online harassment, particularly against young human rights defenders.

Global Witness is continuing to monitor tens of suspected attacks on land and environmental defenders in the Philippines in 2024, which we are unable to accurately verify and include in our database at the time of writing.

Perverting justice: The criminalisation of land and environmental defenders in Asia

In Asia, detentions and criminalisation of defenders are becoming increasingly common. Patterns in the types of laws being used are starting to emerge. Here we analyse these and look at how governments weaponise laws to detain defenders in the region

Honduras

In Honduras we recorded six cases in 2024, compared to 18 in 2023. Five defenders were killed, while one person disappeared.

Four cases were documented in Colón, northern Honduras, a region impacted by ongoing conflict over land reform and water resources. The area is heavily militarised and marred by violence and forced eviction of communities. Three of those killed and disappeared in 2024 were small-scale farmers and members of peasant cooperatives in Bajo Aguán.

One of the killings was of renowned anti-mining activist, Juan López, who was working to protect the Guapinol and San Pedro rivers which serve water to hundreds of people. This is not the first time communities engaged in these struggles have reported violence and been the target of killings.

Honduran anti-mining activist Juan López dedicated his life to the protection of the Guapinol and San Pedro rivers in Honduras. He was killed in 2024. Orlando Sierra / AFP via Getty Images

Who: Defenders targeted

Land and environmental struggles take different forms despite being triggered by the same underlying threats. Some groups of defenders have been disproportionately targeted since we started documenting cases more than decade ago.

In 2024, around a third of those killed or disappeared globally were Indigenous or Afro-descendent (48 and two, respectively), while another third were small-scale farmers (54).

Indigenous Peoples and Afro-descendant defenders make up a third of killings and disappearances

In total, 10% of all murdered (13) or disappeared (one) defenders in 2024 were women – five of them from Mexico.

Violence not only affects individual defenders but can also target whole families, communities and organisations, often in a deliberate attempt to terrorise, intimidate and silence. In 2024, we documented 14 killings of people caught up in attacks on defenders – often family members who were present during an attack. Two of them were children.

Why: Drivers behind the murders

Our years of working with defenders and documenting reprisals against them indicate persistently high levels of impunity. The families of murdered or disappeared defenders, as well as defenders who are subject to non-lethal reprisals, rarely see their attackers brought to justice.

If they are fortunate, the direct perpetrator – usually a hired hitman – may be arrested and tried. But intellectual authors –those who plan and pay for the attack – are seldom charged.

Many of these intellectual authors escape prosecution, often due to state failures to investigate and identify them.

Mexican police guard the National Palace during a protest in commemorating the disappeared in the centre of Mexico City. Luis Rojas / Panos Pictures / Global Witness

This raises questions about the extent of their influence over state institutions, politicians and judicial systems that can criminalise the victims, their communities or even their families – as documented in Chapter Three – and leave the perpetrator unpunished.

Without functioning judicial systems, those behind lethal attacks against defenders rarely face justice. For instance, in Colombia, a country with consistently high numbers of killings, only 5.2% of murders of social leaders and human rights defenders since 2002 have been resolved in court.

The lack of proper evidence gathering as part of normal judicial process also makes it difficult to uncover the underlying causes of the killings and disappearances. Yet, we have been able to connect killings with certain corporate interests.

Mining and extractives remains the deadliest industry for defenders

Once again, mining emerged as the deadliest sector, with at least 29 related cases in 2024. Next came logging with eight cases and agribusiness with four. Road-building and infrastructure projects, poaching and hydropower have also driven deadly attacks in 2024.

Just under a third of all cases we recorded last year were linked to organised crime. Criminal organisations and related illegal economies are thriving around the world, undermining the rule of law, putting defenders at risk and threatening key ecosystems. In places such as the Amazon, they are driving human rights violations, deforestation and institutional corruption.

States are also active perpetrators of violence, with armed forces, police and other government entities linked to 17 killings. Investigating reprisals against defenders is further complicated by the frequent connections between organised crime, government and corporate interests.

Almost a third of killings and disappearances in 2024 are linked to organised crime

Land and environmental defenders in conflict zones

Conflict over land and resources impacts millions of people across the world – and is likely to intensify in the wake of increasing global instability.

The resulting violence and mass displacement caused by breakdowns in the rule of law, and the fracturing of civic space, makes recording violations against land and environmental defenders an ongoing challenge.

Documenting reprisals against land and environmental defenders in Palestine is no different.

Since the outbreak of the conflict in Gaza in October 2023, over 59,000 Palestinians are estimated to have been killed by Israeli operations, with catastrophic environmental damage caused.

Israeli forces have targeted desalination plants and critical water infrastructure, and damaged 80% of the total cropland in the Gaza Strip as of March 2025.

In 2024, two separate international court rulings cited that a case of genocide in Gaza was plausible and ordered Israel to cease military actions aimed at destroying the population.

From October 2023 to May 2025, 926 Palestinian civilians have been killed in the occupied West Bank alone. These numbers barely scratch the surface of the total number of Palestinians suffering due to the ongoing violence perpetrated by Israel in the occupied territories.

Documenting killings and disappearances of land and environmental defenders within these contexts is challenging and has not been possible for 2024.

To do so in the future, it is vital to situate the work of Palestinian defenders within the wider struggle for self-determination and their land and environmental rights.

For just under a century, the Israeli state has propagated political, legal and economic systems that deliberately oppress and marginalise Palestinian communities – both those within Israel and the occupied-Palestinian territories.

The expropriation of Palestinian lands has occurred across the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem through intensified military control and land grabbing – most notably through the expansion of settlements and infrastructure projects.

The Israeli settler population in the West Bank has increased by 332% in the three decades since the Oslo Accords, resulting in the forced displacement of Palestinian communities – including Indigenous Bedouin and farmers.

Checkpoints, military zones and settler-only roads further fragment Palestinian communities and violate their land rights.

Land grabbing can also lead to widespread environmental destruction – itself used as a tool of erasure. Over a million olive trees have been uprooted in Gaza since 2023.

In some cases, the Israeli state has pursued polices to deliberately transform the landscape as part of its efforts to asset territorial control. This includes the afforestation of destroyed villages, militarisation of agricultural zones and the re-designation of land as state land, military zones or nature reserves.

As a result, Palestinian farming communities and herders are often denied access to natural resources essential to maintain their livelihoods and ancestral traditions.

According to a recent report by UN Special Rapporteur Francesca Albanese, corporations have sustained Israel’s illegal occupation and its assault upon Gaza, which a growing number of experts and human rights bodies, both within in and outside of Israel, have described as a genocide.

Corporate interests have been deeply linked to Israeli settler-colonial displacement and dispossessing Palestinians of their land. Sectors like arms manufacturers, tech firms, building and construction companies, and extractive and service industries enable the denial of self-determination and other structural violations in the occupied Palestinian territory.

Environmental laws are selectively applied, protecting Israeli settlers while exposing Palestinian communities to unchecked pollution from industrial zones.

This dual legal system has been widely characterised as apartheid and a violation of the Palestinian right to self-determination by international watchdogs and experts at the UN and International Court of Justice.

A Palestinian woman and a boy examine a damaged olive tree in the West Bank. The Israeli state policies can deliberately transform the landscape as part of its efforts to assert territorial control. Mosab Shawer / Middle East Images / AFP via Getty Image

Alarming shifts in global policy

In recent months, we’ve looked on in alarm as the global environmental and human rights agenda has been delayed, watered down or scrapped altogether.

The US has abandoned the Paris Agreement and the Human Rights Council, while the EU’s Green Deal is being deprioritised, as a growing far-right influence within EU institutions resists the transition to a green economy. The EU has also recently weakened legislation to protect defenders from environmental and human rights abuses caused by companies.

These shifts undermine the potential for decisive and transformative action to protect our planet and those who defend it. They leave defenders more isolated and vulnerable to attack than ever.

Leaders are also failing to implement existing polices designed to protect defenders. In Latin America and the Caribbean, almost 1,000 defenders have been murdered or disappeared since the adoption of the Escazú Agreement – a regional treaty that is designed to protect them – on 4 March 2018.

The Escazú Agreement

The Escazú Agreement is a landmark treaty for Latin America and the Caribbean. It guarantees three key rights:

- Access to environmental information

- Public participation in environmental decision-making

- Access to environmental justice and a healthy and sustainable environment, including the protection of human rights defenders on environmental matters

Critically, it is one of the first treaties of its kind to include specific measures for the protection of environmental defenders.

So far, 24 countries have signed the agreement – all of them countries where we have documented killings or disappearances in 2024. Eighteen states – including Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and Nicaragua – have ratified the agreement.

A total of 1,733 defenders have been killed or disappeared since the adoption of the Paris Agreement on climate change on 12 December 2015.

Ahead of the UN climate conference COP30, it is vital that world leaders recognise defenders’ crucial role in protecting our environment by sustainably managing their lands and territories. This must be reflected in both policy and practice.

We cannot allow the devastating exploitation of land and resources – or the violence against those who resist it – to continue.

A boat travels along a river through remaining intact forest and biodiversity in Acre state, Brazil. Lalo de Almeida / Panos

Guatemala: Alarming rise in murders

Guatemala experienced a sharp increase in the number of killings, jumping from four documented cases in 2023 to 20 in 2024. This figure excludes at least three other documented attacks against land and environmental defenders, which we verified but omitted from our dataset due to fear of future reprisals against the victims’ families.

Regardless, this is still a five-fold increase, with Guatemala now recording the highest number of killings per capita in the world in 2024.

Guatemala had the highest number of killings per capita in the world in 2024

The Protection Unit for Human Rights Defenders (UDEFEGUA), a Guatemalan organisation that monitors reprisals against human rights defenders, also documented a record number of murders in 2024.

It identified 2024 as the year with the second highest number of lethal and non-lethal attacks on defenders in the country since the year 2000. This includes widespread criminalisation, threats and forced evictions, as well as a spate of online attacks.

Concerned about judicial corruption and impunity, Indigenous communities gather for a demonstration in Guatemala City. Fernando Chuy / Zuma Press Wire

Political shifts and violence in Guatemala

On 15 January 2024, Bernardo Arévalo became the president of Guatemala. His party, Movimiento Semilla, won the election on a mandate to fight corruption, tackle rampant inequality, and rectify the long-standing neglect, exclusion and discrimination against Indigenous Peoples.

His historic win took place after decades of democratic backsliding and heightened repression. Nearly all political, public and judicial institutions were widely believed to be infiltrated by corrupt elites – known as the "pact of the corrupt".

Transparency International ranked Guatemala as the fifth most corrupt country in Latin America in 2024.

The Public Prosecutor's Office challenged the election results in an attempt to prevent the new government from taking office and protect elite vested interests. However, widespread support, including from Indigenous Peoples – who comprise around 44% of the country’s population – ensured that democracy prevailed and President Arévalo’s government was installed.

Within weeks of his appointment, Arévalo signed an unprecedented agreement with key peasant organisations to promote access to land and resolve the many ongoing agrarian conflicts. But despite the more inclusive political agenda, there was a sharp increase in attacks against defenders in 2024.

A spike in violence against defenders is not uncommon following election swings. We previously recorded upticks in attacks against defenders in Colombia and the Philippines following the elections of authoritarian presidents Ivan Duque and Rodrigo Duterte in 2018 and 2016 respectively.

Conversely, moves towards more egalitarian politics can disrupt the entrenched control of political and business elites – often triggering social unrest and increased violence.

Decades of corrupt deals between political and corporate interests in Guatemala have enabled widespread exploitation of the country’s natural resources. Mines, hydroelectric dams and plantations threaten Indigenous livelihoods, pollute the environment and displace communities.

Those opposing extractive capitalism and protecting land rights face threats, violence and murder – with at least 106 land and environmental defenders killed or disappeared in the country since 2012.

At the heart of much of the violence in Guatemala over the years is the challenge of land distribution and the need for agrarian reform – which would change laws or customs regarding land ownership, land use and land transfers – to address land inequality and tenure.

The violence stretches back to the colonial period and was exacerbated by 35 years of armed conflict ending in the mid-1990s, which enabled elites to accumulate large tracts of land.

Colombian social leaders share their knowledge of sustainable forest management with farmers living in the rainforests of northern Guatemala. Johan Ordenez / AFP via Getty Images

Another factor is the lack of protection for Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Protecting Indigenous Peoples’ rights was finally incorporated into the Guatemalan Constitution in 1996. But strengthening Indigenous and traditional land rights remains one of the country’s most pressing challenges.

With an estimated 75% of its Indigenous Peoples living in poverty, land reform is vital to address rampant inequality and prevent wider conflict over natural resources.

Of the 106 documented killings and disappearances in Guatemala since 2012, half were Indigenous Peoples and a fifth were small-scale farmers defending land rights or opposing natural resource extraction. In 2024, 13 defenders were killed for protecting their land rights – 10 of whom were Indigenous Peoples or small-scale farmers.

The rise of organised crime is another factor putting defenders in Guatemala at risk. Between 2012 and 2024, over half of all attacks took place in four regional departments: Alta Verapaz, Izabal, Jalapa and Huehuetenango. Authorities have recently uncovered large coca plantations in Alta Verapaz and Izabal, pointing to an illicit drugs trade.

In 2024, eight defenders were killed in the coastal province of Escuintla. Six of these murders were linked to organised crime. Escuintla’s proximity to Mexico, and its ports on the Pacific coast, have made it a strategic throughfare for the drugs trade – fuelling violence and conflict over resources during the past decade.

Attacks have been particularly fierce against Indigenous and farmers’ organisations trying to protect their land rights. Six of the defenders killed in Escuintla in 2024 were affiliated with Comité Campesino del Altiplano (CCDA) – a peasant movement of rural producers and artisans advocating for social and environmental equality.

Opaque appointments, arbitrary rulings and the use of prosecutors' offices to shield corrupt networks have bolstered a culture of impunity, increasing the risks to defenders, according to analysis by Guatemalan human rights groups.

Ensuring an independent, impartial and effective justice system is paramount to stop the criminalisation of defenders and safeguard democracy according to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Independence of Judges and Lawyers.

This condition is necessary for the successful implementation of international treaties, including the Escazú agreement – Latin America and the Caribbean’s landmark treaty guaranteeing justice for environmental harm – which Guatemala is yet to ratify.

How we collect and analyse data

Global Witness documents the killings and disappearances of land and environmental defenders globally. Since 2012, in partnership with over 30 local, national and regional organisations in more than 20 countries, we have produced an annual report containing the number of killings and disappearances.

Land and environmental defenders are a specific type of human rights defender. They are individuals or groups of people who promote, protect or strive to uphold human rights through peaceful action. We define defenders as people who take peaceful action against the unjust, discriminatory, corrupt or damaging exploitation of land or the environment.

Land and environmental struggles are shaped by the local context and take different forms – whether that is striving against systematic land dispossession and environmental destruction or preventing the degeneration of sovereignty, culture, livelihoods and homes. Others are caught in wider armed conflicts which exacerbate land, environmental and climate injustices.

We are alerted to attacks by reliable online reporting, tip-offs and wider documentation efforts from civil society organisations. We set up search engine alerts using keywords and verify information by cross-referencing details with additional sources, working closely with organisations supporting defenders and their communities.

Underreporting and challenges in verifying data mean the figures presented in this report are incomplete and likely to be an underestimate. They should be considered as only a partial picture of the extent of killings and disappearances of land and environmental defenders.

Learn more about our methodology, reporting criteria and the organisations we work with

Documenting killings and disappearances of land and environmental defenders

Every year, Global Witness works with partners to gather evidence, verify and document every time a land and environmental defender is killed or disappeared. Our methodology follows a robust criterion, yet undocumented cases pose challenges when it comes to analysing data

Defender Gloria Ita advocates for the protection and sustainable management of the Ekuri forest. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

Forest defenders

Protecting nature and biodiversity in Nigeria

For the Ekuri community – Indigenous Nkukorli Peoples – in Nigeria, the forest is everything. In protecting it, and using its resources sustainably, their patch of tropical forest sustains them – and has done so for generations. But with increased pressure on their local resources comes increased conflict.

Defenders Louis Friday, Martins Egot and Odey Oyama share their community’s connection with the forest, and how extractive companies are threatening both the Ekuri community and their forest’s future.

“Our livelihoods depend on the forest,” explains Louis Friday, an environmental activist from the Ekuri community in Nigeria.

For generations, the Indigenous Nkukorli Peoples – who live across two villages nestled within the Cross River Rainforest – have relied on one of Africa’s last remaining tropical forests.

Activist and Indigenous defender, Louis Friday, works to protect the biodiverse 33,600-hectare Ekuri forest which is under threat from illegal and state-backed logging. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

Cloaking the southern coast of West Africa, the forest forms one of the planet’s 36 biodiversity hotspots. It hosts a panoply of endangered species – including Cross River gorillas, forest elephants, pygmy hippopotami and red colobus monkeys.

“We get a lot of products, medicines, foods, materials from the forest: the Ijuóó, the African bush mango; a leafy green called afang; and ekaa, a thick cane rope used for construction and furniture,” Louis says, sharing names in the Indigenous language of Lokorli, spoken only in Ekuri.

“The forest keeps our streams intact and ensures they never dry out in any season. It keeps our air clean,” he adds.

But over the past few decades, the Ekuri’s forest has faced waves of threats. Logging companies have descended, promising to build roads in exchange for a piece of the forest.

Award-winning community conservation

As trees in neighbouring communities fell to loggers’ chainsaws, Ekuri leaders took action. In 1997, they set up the Ekuri Initiative to protect and communally manage their 33,600 hectares of tropical forest.

“Everybody supported the idea: the community, youth, women,” says Martins Egot, a former Chairman of the Ekuri Initiative and Executive Director of environmental organisation PADIC-Africa. “It was an example of the importance of grassroots management, balancing conservation with revenue and income.”

The initiative surveyed the forest and developed a forest management plan, dividing it into protected areas and zones for community use, from farming to the production of non-timber products. It built a road connecting Ekuri villages, installing bridges and culverts along the way, and it trained "eco-guards" to patrol, document and denounce illegal logging.

Lawrencia Agbor dries cocoa outside her home. The forest provides food, medicine and clean air for members of the Ekuri community. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

It also established clear community guidelines for the selective harvesting of timber products. Every Ekuri community member had the right to harvest trees for their own use, but not for commercial sale – sales were controlled and could only take place through the Ekuri Initiative.

This differs from many other communities, where people have claimed forest areas then sold them to logging companies, accelerating deforestation.

This was a very good time for us. We were using the forest sustainably, flora and fauna were intact, and wildlife was thriving

The community’s conservation efforts won a UN conservation prize. They protected livelihoods, preserved critical ecosystems and safeguarded spiritual and cultural values passed down through generations.

However, the success of the community initiative was short-lived.

Ekuri leader, Lawrencia Agbor, holds a young rescued monkey, one of the many threatened species affected by habitat loss due to logging in the Ekuri forest. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

Choking community-conservation efforts

In 2009, the Cross River State government introduced a moratorium – or ban – on logging.

“This erased our ability to sustainably harvest and market timber, sweeping away an important revenue stream. At the same time, instead of eradicating the local timber trade, it pushed it into the hands of criminal groups,” explains Martins.

Shortly after the moratorium took effect, a second threat emerged. In 2015, the Cross River State government announced plans to build a six-lane superhighway straight through 52km of Ekuri community forest.

The plans included a 10km buffer zone on each side of the highway – threatening to wrench a vast swathe of Ekuri forest from the community. It would also rip through the heart of Cross River National Park.

Furious, the Ekuri community resisted the proposed project. Martins and other community leaders from Ekuri and the surrounding area travelled to Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, to meet with environment ministry officials. They sent petitions to the state government, demanding to see the project’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA).

Our small community movement generated support from across Nigeria and globally. People sat up and saw the benefits of community conservation

"Activists and affected communities marched to the Federal Ministry of Environment to submit our petition – which over 100,000 people signed – opposing the proposed superhighway project,” recalls Martins.

A teacher and forest defender, Gloria Ita, advocates for the sustainable management of forest resources to preserve the environment and promote Indigenous Nkokoli culture for future generations in Ekuri. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

The Federal government rejected three EIAs submitted by Cross River government, and yet in 2015 – without community consultation – initial construction work on the highway began. It damaged forests and destroyed neighbouring homes and farmland.

The Ekuri Initiative, alongside civil society groups and international partners, collected more than 100,000 signatures from across the world, opposing the proposed superhighway project.

In an act of peaceful protest, activists and members of affected communities delivered the petition to the Federal Ministry of Environment calling for the protection of the environment and local livelihoods.

Eventually, thanks to public pressure, the original proposal was pulled in 2017, and a new route was proposed which largely avoided the Ekuri villages – the project has since been abandoned.

It was a major victory. But for the Ekuri villagers, the damage had already been done. The superhighway’s initial construction had opened tracks into new areas of the Ekuri forest, providing access for illegal loggers. And with Ekuri’s revenue stream choked by the 2009 moratorium, poverty and division grew within Ekuri itself.

Ongoing illegal logging in Ekuri forest. Ekuri leaders have estimated that logging activities have destroyed more than 40% of the community’s forest since 2018. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

Threats to Nigeria’s forests and its defenders

The years since have brought a succession of challenges – placing the forest at greater risk than ever before. The Ekuri Initiative ceased to function, and the forest it once managed proceeded to be felled and trucked away by illegal loggers and large companies.

Pressure comes from corporations moving into the area and continuing to deforest. Things have worsened since the Cross River government lifted the logging moratorium in 2023. Martins estimates that logging activities have destroyed more than 40% of the community’s forest since the moratorium was invoked in 2018.

“When the state government relaxed the moratorium, the chair of the Forestry Commission invited timber companies to register, pay and then log,” claims Martins. “Based on the amount of destruction we document in the field, I believe logging must generate some of the highest revenues for the state.”

The arrival of logging companies has also sparked division within forest communities. Younger people – seeing other communities cutting deals with loggers – are worried that resource conservation might not help address poverty and lack of basic infrastructure.

The resulting destruction would not only harm the forest but also sometimes slowly drain the resources communities relied on.

“That made the young men say, ‘Look, we can't be sitting here and doing conservation while others are eating into our resources from the flanks,’” Martins says. “To survive, they are forced to be part of the timber business.”

Defender Martins Egot was instrumental in halting the proposed Superhighway Project, which would have destroyed large parts of the forest. He later founded the eco-guards, a team of volunteers trained in forest management. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

Some of the community are increasingly worried that illicit logging is also conducted with the state government’s consent. Former government officials have echoed community concerns about official complicity with illegal logging.

Frank Eja, a director at the Cross River State Forestry Commission, acknowledged in 2023 that officials accept payments to turn a blind eye to illegal timber leaving the state.

“Each trailer must pay N500,000,” (about US$325) he told investigative outlet African Arguments – a fee he alleged is shared among top state government officials. A logger cited the very same figure in a recent investigation by national newspaper the Premium Times: “We pay N500,000 for every truck.”

With little support from the federal government or Cross River Forestry Commission, the Ekuri community was forced to compromise. They set up a registration system for loggers, allowing them to take timber from the forest in return for payment. That way, at least some logging money would benefit the community, instead of being lost to corruption.

“This was not the intention of the Ekuri people,” Louis says. “We did it out of duress because government policy was not backing us up.”

Chief Abel Egbe sits in his house in New Ekuri, home to the Indigenous Nkukorli Peoples. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

The cost of speaking out

Speaking out against the destruction has always been dangerous work. “There were arrests in the early days,” says Louis.

In 1996, Ekuri chief Edwin Ogar and five other community members were arrested and sentenced to two years in prison with hard labour for obstructing road access to a logging company.

“This was an attempt to silence collective action and reward loggers looking to benefit at the cost of community wellbeing,” he warns.

“There's a huge level of conspiracy in the logging operation. Most of the concessions and permits are fake,” he alleges, with limited state action taken to quell abuses.

In early 2020, Odey’s taskforce impounded three trailer-loads of illegal timber products. He asked the police to take custody of the goods pending further instructions. But days later, the head of the state’s Forestry Commission ordered the police to release them.

Frustrated with such apparent endemic corruption, Odey quit his post as taskforce chair after just four months.

Eco-guards set off into the Ekuri community forest to monitor and document logging activities. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

Following allegations that a local timber company was logging in and around Ekuri forest without permission, Ekuri’s eco-guards repeatedly confiscated company equipment in 2023.

Community members allege that company representatives responded by arriving with 30 armed soldiers, flexing their connections with the state.

According to a submission to the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders and Nigeria’s Environment Minister, the security forces advanced towards the villagers on motorbikes and opened fire. The villagers had to flee for safety.

Threats to those defending the forest are serious and escalating.

In January 2025, I was arrested by a team of over 40 police officers wearing masks and holding guns

Odey and four other RRDC employees were charged with promoting inter-communal war, which carries a penalty of life imprisonment. Odey believes attempts to criminalise him stem from his work as forest defender – and his opposition to corporate logging in the area.

Such official corruption makes resisting illegal logging a perilous task. “It’s dangerous, a very dangerous activity,” Odey says. “You can easily be killed. I have just been lucky.”

Bad roads, caused by ongoing logging activities, makes it difficult for communities to remain self-sufficient and sustainably manage the forest. Taiwo Aina / Global Witness

Despite the risks, forest defenders in Cross River like Louis, Martins and Odey aren’t about to back down. Martins hopes the Ekuri Initiative can be revived, calling for “external support” to strengthen the community’s institutions. Louis agrees, stressing the situation’s escalating urgency.

“Forest resources the community relies on are disappearing. Streams are drying up – their sources now exposed and evaporating under the hot sun. In a rapidly warming climate, things are only likely to get worse,” he says.

“A holistic approach to forest conservation is needed, one where communities like ours are supported to overcome their struggles and sustainably manage the forest ourselves.

"As well as stronger enforcement of logging laws and resourcing of forest eco-guards, we also need clean energy sources such as solar and, critically, improvement to transport and road infrastructure so that we can remain self-sufficient without over-relying on the forest to provide.

“These are the real means to help the Ekuri people,” Louis concludes. “By addressing these systemic issues, pressure on the forest will be a thing of the past.”

Defender recommendations

Nigerian organisations PADIC-Africa and Rainforest Resource and Development Centre (RRDC) call on the Nigerian state to:

- Establish a multi-stakeholder panel to review and update the Cross River State Forestry Commission Law (2010). The Cross River government should strengthen enforcement mechanisms and prioritise community-based forest-management practices. Instruments to protect eco-guards and mitigate threats, intimidation and violence against them should be bolstered and expanded to forest defenders and communities.

- Set up an independent forest governance oversight committee in Cross River State with representation from local communities, CSOs and legal experts. It would monitor the activities of the Forestry Commission and law enforcement agencies.

- Increase the budget allocated to the Forestry Commission to hire, train and equip forest enforcement officers, empowering them to implement the protection provisions set out in the Cross River State Forestry Commission Law (2010). Financial support should extend to local forest-watch groups, including community eco-guards who conduct forest surveillance.

- Review and strengthen existing laws and regulations to protect human rights and land and environmental defenders. This should include a witness protection programme for people who testify against corporate abuse and illegal activities. Attacks against defenders must be investigated promptly and transparently, with improved communication between investigating authorities, defenders and wider communities. Security training and financial support for at-risk defenders would help mitigate and prevent future reprisals.

Lissette Sánchez continues the search for her grandmother, Julia Chuñil. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

Earth defenders

Julia Chuñil is an Indigenous Mapuche from Los Ríos, Chile. President of the Putreguel de Máfil Indigenous community, she had been working to secure tenure over their ancestral lands. But following threats over a contested area of forest, Reserva Cora, Julia disappeared.

She has now been missing for nearly a year. Riddled with controversy, discrimination and diversions, the case has left Julia’s family with countless questions and little access to justice.

Julia Chuñil knew she was at risk. She had been telling her family and friends for years. At 72 years old, she was living alone in a remote wooden cabin at the foot of the Valdivian forest in the Chilean region of Los Ríos – around 800km south of the capital, Santiago.

The native forest surrounding her modest cabin had slowly succumbed to a checkerboard of pine and eucalyptus plantations. For Julia, this was not just a danger for the region’s unique biodiversity but also threatened her and her community’s ancestral rights as Indigenous Mapuche.

A land defender, she was determined to protect the forest and preserve her community’s sacred connection with their land and nature. This made her vulnerable.

On 8 November 2024, Julia left her home, accompanied by her dog Cholito, to search for some missing farm animals. The animals returned – but Julia and Cholito have not been seen since.

Lissette Sánchez lights a candle to honour her grandmother, Julia Chuñil, a Mapuche defender who has been missing since November 2024. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

For years, Julia had led efforts to reclaim ancestral land rights for her community. It was an essential step towards securing the livelihoods and the self-determination of Mapuche Indigenous Peoples.

But as president of the Putreguel de Máfil Indigenous community, her leadership made her an obvious target. She experienced constant harassment by a local businessman and was allegedly repeatedly offered money to leave the area.

“My mother was born and raised in this region of Chile. She learned about land dispossession early on, and this led her to a lifelong commitment to reclaim the lands of her ancestors,” says Pablo San Martín, Julia’s son.

Her land was her life, and she had devoted herself to taking care of it and of the local environment. If a single tree was chopped down, she’d notice. She knew this place so well. Her land was the only place she wanted to be

A well-known Mapuche leader, Julia’s disappearance sparked widespread concern. Over a hundred volunteers from across Chile joined the search lasting weeks, led by her family. During this initial search, her family say tyre tracks were found nearby, leading them to suspect foul play and the involvement of others in her disappearance.

Fearing the worst, they, supported by Chilean organisation Escazú Ahora, filed a criminal complaint for kidnapping, homicide and femicide.

From the outset, Julia’s family have had to fight for state acknowledgement of her role as a land and environmental defender.

Julia's son Pablo Marcelo San Martín Chuñil points out areas of land near his mother's home which have been cleared by logging companies. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

They believe institutional discrimination against Julia, and against them, as Mapuche peoples has inhibited the investigation into her disappearance.

A 2009 UN expert report details allegations of procedural irregularities and discrimination against Mapuche peoples mainly in the context of disputes over claims to lands and natural resources, with frequent complaints of “excessive and disproportionate” use of force.

Allegations on the lack of state recognition of defenders’ situations in Chile have also been raised in a report by the UN International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination in 2022.

We have been treated like the perpetrators rather than the victims. This excruciatingly hard thing has happened at the heart of our family, yet the investigations have been focused on us. We’re suspects

Despite authorities’ ongoing investigation into Julia’s disappearance, unverified details have surfaced in media reports, indicating that authorities have treated Julia’s family as suspects.

Julia’s daughter, Jeannette Troncoso, has been subjected to particularly extreme harassment. A large deployment of police and staff from the prosecutor’s office forcefully raided her home seven times.

In one incident, a police officer interrogated her in the presence of the local prosecutor. In later testimony published by the IACHR resolution, Jeanette described how the officer’s questions rapidly turned into an aggressive inquisition, with her interrogators accusing her husband of murdering Julia and Jeanette of being complicit.

Jeannette Troncoso looks out the window of her home hoping for her mother's return. Jeannette has been subjected to harassment and was accused by police of being complicit in the murder of her mother, Julia Chuñil. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

“My sister and brother’s home has been searched as if they had something to hide, and this has diverted attention away from investigating the actual perpetrators. We have provided the police with information, videos, audio materials, all pointing to the involvement of certain people.

“It is hard to understand what we might have done that merits this treatment. And it has resulted in the waste of precious time over the first months, where a lot more progress could have been made.”

This has fuelled a narrative that Julia’s family were somehow behind her disappearance. Her family and lawyer have called on the Supreme Court to review the police approach and stop treating them as suspects. Like so many defender cases, the legal system that should have been there to help was instead turned against them.

Family members and friends of Julia Chuñil search for her on the disputed land, where she was last seen in Máfil, Chile. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

Julia’s case is not an isolated incident. For years, violence against the Mapuche peoples has been rife.

Between 2012 and 2024, Global Witness documented the murder or disappearance of five defenders in Chile – four of whom were Mapuches. Chilean state forces allegedly murdered at least two of them.

Over the past decade, several other Mapuche land defenders have been found dead in suspicious circumstances. These deaths are often inadequately investigated and quickly brushed aside.

Other forms of violence against land and environmental defenders in Chile are also pervasive, including criminalisation through anti-terrorist laws, harassment, threats and false accusations.

The Mapuches’ struggle for land rights

Known as “people of the earth”, the Mapuche are the largest Indigenous group in Chile, with almost 1.8 million people, and are also present in Argentina.

Like other Indigenous Peoples across the world, government failure to address historic land grabs and affirm their rights has left them struggling to secure tenure over their ancestral lands.

Alongside Uruguay, Chile is one of the only countries in Latin America whose constitution does not recognise Indigenous Peoples and their individual and collective rights.

Following years of dispossession, the Mapuche have a long history of fiercely defending their rights to ancestral land, bringing them into conflict with the Chilean state.

For decades, relationships between Mapuches and the state have been fraught with periods of heavy-handed policing and the militarisation of Mapuche lands.

In recent years, the tightening grip of large-scale construction and logging concessions within Mapuche territories has intensified the conflict over land. As a result, a minority of Mapuche groups have been radicalised and have resorted to violence.

In response, President Gabriel Boric declared a controversial constitutional state of exception – similar to a state of emergency – in 2022, allowing him to increase the deployment of military forces on Mapuche lands across southern Chile.

A year after the declaration, Boric established a Presidential Commission for Peace and Understanding to help find a long-term solution to the land conflict.

In May 2025, the Commission published a report highlighting the need for justice, recognition and reparation for the Mapuche people.

The report doesn’t, however, clearly mention Indigenous communities’ crucial role as guardians of land or propose protection mechanisms for land and environmental defenders. As it stands, this represents a missed opportunity to mark the start of a new era in Chile.

In a promising move, however, President Boric announced a new bill to recognise Indigenous Peoples in the Chilean Constitution in June 2025.

Indigenous Mapuche leaders support Julia Chuñil's family and search the area where she was last seen. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

The dangers of reclaiming ancestral lands

By the time she disappeared, Julia and her community had spent years attempting to reclaim ancestral lands in Máfil – an arduous process, with mixed success.

In 2014, Julia applied for legal recognition for her Indigenous community with the Indigenous Development National Corporation (CONADI) and started the process of reclaiming a 900-hectare area known as Reserva Cora Número Uno-A – or Reserva Cora.

Prior to this, the rights to Reserva Cora had passed through several hands. CONADI had previously awarded the land to another Mapuche community, Blanco Lepin, in 2011 – despite them living in a different region. At the time, it was listed as property of a local businessman, Juan Carlos Morstadt, owner of several forestry, agriculture and livestock companies.

Blanco Lepin began the process of buying the land from Morstadt, but the sale became marred with irregularities. CONADI appears to have later transferred over USD $1 million for the property according to an investigation by Resumen Latino Americo.

Morstadt is alleged to have rescinded on his contractual obligations and provided false information to Blanco Lepin about the quality and size of the land. As a result, the community requested an annulment of the sales contract and filed a complaint against him.

Morning mist covers the ancestral land that Julia Chuñil was trying to protect before she was disappeared in November 2024. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

After Blanco Lepin left in 2015, Julia moved to Reserva Cora and took over the land on behalf of her community. Julia believed that local businessmen, including Morstadt, wanted to get hold of the reserve again to log and sell the timber. According to her family, she was determined to protect it – and the flora and fauna within it.

A few years later, the harassment started.

“Morstadt offered my mum money to leave on several occasions, but she always refused to accept it,” recalls Pablo.

The pressure kept piling on. Before her disappearance, Julia told her family she felt increasingly coerced to leave Reserve Cora. She told them: “If something happens to me, you know who it was.”

According to Julia’s family, Morstadt had threatened her and other community members numerous times. There has to date been no evidence to link Morstadt directly with Julia's disappearance.

Julia also told her family that Morstadt warned her of his power and influence in the broader community and suggested he was the reason CONADI did not support her. She saw this as an attempt to deter her from seeking support from local authorities.

Julia Chuñil's son, Pablo Marcelo San Martín (left) and his stepfather, Bermar Flavio Bastías Bastidas (right), look over land cleared by logging companies. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

In 2017, Morstadt legally took over Reserva Cora again. But CONADI never informed Julia or her community. This highly questionable process saw Morstadt keep the land allegedly without paying CONADI a penny.

For Indigenous communities like Julia’s, securing land tenure, including collective tenure, is essential: land means livelihoods, food security, self-determination, cultural identity and environmental protection.

But Julia’s experience demonstrates how Indigenous Peoples are forced to confront unpredictable challenges as they attempt to reclaim their ancestral lands – often with dangerous consequences.

In 2023 and 2024, campaign group Escazú Ahora documented 82 rights violations against 47 land and environmental defenders in Chile. The level of physical attacks has tripled between 2023 and 2024, including murder attempts and physical assaults.

Almost 40% of the threats and more than 90% of physical attacks in 2024 were directed at forest defenders. Just over 70% of the registered cases in 2024 involved women, with nearly half of all cases including physically assault – many victims were attacked multiple times in various ways, including violence against their children.

The path ahead: Justice for Julia

Since her disappearance, Julia’s family has pursued every possible avenue to find her, exposing them to continued threats and intimidation. In April 2025, her family denounced attacks on animals at Julia’s home: a pig was found dead with gunshot wounds beside the body of her horse, which the family suspects was poisoned.

The remains of Julia's horse, which the family suspects was poisoned, lie near their home. Since her disappearance, Julia’s family have been exposed to threats and intimidation. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

“My siblings and I had agreed on the phone to auction those two animals to be able to cover the legal costs,” explains Pablo. “A few days after our conversations, the animals were found dead. To us, this is not only an intimidatory tactic. It is, above all, a deliberate attempt to prevent us from fighting this case in court by stifling us financially. This all feels like a setup.”

And yet, Julia’s family has no intention of ending their quest for justice.

My mum had the courage of building this community, she brought us all together to fight for our rights to our ancestral lands. Some turned against her because she sought the common good rather than private gains

“All we are asking for is a full, fair investigation to take place. It’s been almost a year since she disappeared and we’re still in the dark about what happened. We want those behind this to be identified and charged,” Pablo concludes.

In July 2025, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) granted precautionary measures to Julia, urging the Chilean state to take urgent action due to the risk of irreparable harm and expressing concern over the lack of progress.

The commission called on the state to intensify its efforts to find Julia, investigate the events surrounding her disappearance, and keep her family informed.

A lone chair sits inside Julia’s house, left abandoned after her disappearance. Tamara Merino / Global Witness

Defender Recommendations

Chilean organisation, Escazú Ahora Chile, calls on the Chilean state to:

- Adopt urgent, effective and coordinated measures to accelerate the investigation into Julia Chuñil’s disappearance. The state must officially recognise her work as a land and environmental defender, working to protect native forests, ancestral territories and her community’s rights. This should be considered across all lines of investigation, search efforts and investigations into previous alleged harassment in line with Article 9 of the Escazú Agreement – requiring parties to take appropriate, effective and timely measures to prevent, investigate and punish attacks, threats or intimidation against defenders.

- End the militarisation of Indigenous territories via the use of "state of emergency" measures and public order functions, which restrict Indigenous Peoples’ and defenders’ freedom of movement, association and protest. Failure to do so violates the fundamental rights of rural communities, Indigenous Peoples, and land and environmental defenders – and increases the risks they face.

- Cease involvement in transactions, agreements or processes for the purchase or sale of Indigenous lands with any individuals or entities under investigation for harms against defenders or acts of public corruption. This will ensure CONADI's agreements with external parties are transparent and can be adequately scrutinised.

- Support the draft congressional law 16886-12 regulating the protection of nature and human rights defenders. The proposed law recognises and provides comprehensive protection to land and environmental defenders, ensuring a safe and enabling environment without fear of reprisals. It also establishes clear sanctions against perpetrators.

- Establish a national protection system guaranteeing specialised legal and psychosocial support, as well as ensuring open and transparent communication with both individual defenders and organisations. This must provide rapid emergency response, be free of bureaucratic obstacles and founded in principles of equity and accessibility, and be culturally sensitive – building on the lived experiences of defenders. Any protection system must have adequate human and financial resources.

Social leader Jani Silva discusses the risks of travelling back to her home in the Perla Amazónica Peasant Reserve Zone after receiving threats from illegal armed groups operating in the Putumayo region, in Colombia. Erika Piñeros / Global Witness

Preventing attacks

Living under state protection in Colombia

Jani Silva is a prominent social leader and central figure within Colombia’s peasant movement. In 2000, she helped create the Perla Amazónica Peasant Reserve Zone in Putumayo – one of Colombia’s first protected peasant reserves, with biodiversity preservation at its core.

But successfully protecting her land has come at a high cost. Living in Putumayo, one of the most dangerous regions of Colombia, Jani has been subject to threats and harassment for years.

After facing death threats and attempted assassinations, Jani and her organisation, Asociación de Desarrollo Integral Sostenible Perla Amazónica (ADISPA), successfully appealed for state protection.

Jani has now lived under protective measures for more than 11 years. While these measures have been lifesaving for her, they have also acted as a barrier to her activism. Here she explains why more must be done to ensure protection measures can truly respond to defenders’ needs.

Jani Silva lives in one of Colombia's most dangerous regions and has been subject to threats and harassment for years. After facing death threats and attempted assassinations, she successfully appealed for state protection. Erika Pineros / Global Witness

“For years, I have been relentlessly threatened, intimidated and followed. So much so that I have been forced to temporarily relocate numerous times, including after learning of a plot to assassinate me.

"I know I’m not alone facing such extreme threats. At least 22 defenders have been murdered or disappeared in my region of Putumayo since 2015, according to Global Witness. But in Putamayo, extractivism and militarisation go hand in hand.

"Over the years, we’ve found ourselves caught in a battleground where control over land and resources is the goal. I have long resisted the intrusion of mining and oil companies, as well as armed groups seeking to control our territories and drug corridors in the southwest of Colombia.

"Their iron-grip has affected us all. Illegal roadblocks have sprung up, enforced curfews have kept us hostage, and violence has become rife – particularly against any social leaders who dare to speak out. All this to see off rivals and maintain territorial control over coca-growing areas, which fuel a rampant drug trade across the border to Ecuador and Brazil.

"Colombia has enormous land inequality, with over 80% of productive land in the hands of the wealthy few. But we have a different relationship with the land and forest. There is no place for unfettered expansion by corporate and illicit groups driven by greed.

"Rather than rows of monocrops, we want to see diversity born through sustainable living and respect for the natural world. This is our philosophy and way of life.

In 2000, Jani Silva helped create the Perla Amazónica Peasant Reserve Zone in Putumayo, one of Colombia’s first protected peasant reserves. Erika Piñeros / Global Witness

The need for protection in the Perla Amazónica Peasant Reserve

"Our territory is everything. It’s where we live; it feeds and sustains us. Together with 600 other families at the Perla Amazónica Peasant Reserve Zone, we collectively manage our lands, develop our own local economies, and ultimately bring peace and social justice to some of the most violent regions of our country.

"This was one of our objectives in establishing the reserve all those years ago. We wanted to secure our rights as a peasant community over the land – which for generations has not been fairly recognised by the Colombian government.

Jani Silva’s son, Edwin Rengifo Silva, checks on the bees at the meliponary in Perla Amazónica Peasant Reserve Zone in Colombia. Erika Pineros / Global Witness

Drivers of violence

After decades of armed conflict, which has claimed the lives of at least half a million people, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) signed a peace agreement in 2016.

Central to the agreement was finding a solution to illegal crop production and drug trafficking, a key driver of violence and symptom of poverty, institutional weakness and active criminal organisations.

In 2017, following the signing of the peace agreement, the Illicit Crop Substitution Programme (PNIS) was established. It aimed to encourage farmers and communities to voluntarily replace coca plantations with other crops, driving structural transformation.

Between 2016 and 2018, the Colombian government signed collective substitution agreements with more than 180,000 families, though only 1.5% of them have received all the promised support. For many communities, coca cultivation remains one of the only viable ways to make a living.