French multinational Veolia could be risking health impacts including birth defects by pumping toxins from a large landfill into protected wetlands in Colombia, a new Global Witness investigation has found

Poisoned Ground: Secretly filmed footage shows Veolia pumping toxic pollutants into protected Colombian wetlands

Download ResourceGlobal Witness obtained a series of videos secretly filmed within the Veolia-managed site that show employees using electric pumps to dump untreated liquid pollutants, known as leachate.

We then commissioned tests of sediment samples, taken in September 2024 from points downstream of the leachate dumping seen in the videos, which revealed high concentrations of heavy metals – including mercury 25 times over safe limits.

San Silvestre Environmental Technology Park. The leachate pool and treatment facility featured in the videos obtained by Global Witness can be seen at the top left of the site. Leonardo Granados / Global Witness

Mercury exposure is associated with a range of serious health complications, including impacts on pregnant woman and infant brain development. Local people had previously sounded the alarm over malformations and illnesses in newborns and young children, which they believed to be linked to the landfill.

Veolia denied that any mercury contamination identified by the tests could result from their activities, sharing internal monitoring data which showed no presence of the heavy metal. The company disputed that Global Witness’s investigation showed "causality" between the video content and the sediment test results.

However, expert analysis commissioned by Global Witness – which found the videos showed “egregious and shameless malpractice” – concluded that Veolia’s testing was insufficient to allow the landfill to be ruled out as the source.

A toxic asset

Veolia, which claims to be the “benchmark company for ecological transformation”, acquired the landfill in 2019 after buying its previous owner, Rediba.

Rediba was also accused of dumping toxins at the site, with environmentalists documenting mass die-offs of fish and other wildlife.

A local paediatrician denounced a surge in birth defects, including babies being born with no brain and a rare skin condition known as Job, which can cause serious skin infections and scarring.

Wetlands downstream of the landfill supply drinking water to 200,000 people in the nearby city of Barrancabermeja, where the pediatrician, Dr Yesid Blanco, had his practice.

Dr Blanco and several other activists subsequently fled the area after receiving death threats from paramilitary groups. While this occurred before Veolia’s management of the site, Colombia’s troubled history makes Barrancabermeja one of the most dangerous places on the planet to speak out about environmental threats.

“Defending the right to a healthy environment shouldn’t be a courageous act, but an unbreakable commitment of all societies,” Dr Blanco told Global Witness from exile.

When Global Witness approached Veolia in 2023, the firm dismissed Dr Blanco’s concerns as “supported exclusively by his personal media statements.”

It claimed to have “reinforced and modernized the treatment process” since taking over the site, adding that “all leachate is treated within the plant’s premises using reverse osmosis technology.”

The new evidence directly contradicts this claim.

The videos, which Global Witness understands were filmed between August and September 2023, were first supplied to a local NGO named San Silvestre Green.

With San Silvestre Green, we flew a drone over Veolia’s site and verified that they were filmed within the property.

We also asked Source International, an independent group of scientists specialised in the impacts of industrial pollution on public health, to review the footage. Their director, Flaviano Bianchini, called it “clear evidence of egregious and shameless malpractice.”

The recordings show untreated leachate being pumped from a containment pool into the wetlands beyond the Veolia site. In one video, the site’s treatment facility is clearly seen to be non-operational while the dumping is taking place. The leachate should be treated and decontaminated on site.

Footage filmed within the Veolia site shows how the firm's treatment facility is non-operational as leachate is being dumped

Leachate has been described as "landfill tea", a liquid pollutant brewed by the percolation of rainwater through waste. It can be “extremely toxic to the environment”, according to one scientific study, with impacts including “eutrophication of aquatic systems and toxic effects on fauna.”

In two other videos, pumps – a large, motorised pump, and a quieter submersible pump – are used to extract untreated leachate from the pool and dump it in a channel flanking the west of the landfill. Site analysis shows that the leachate flows down the channel and into the reeds and water of the wetlands to the north of the Veolia property.

Footage filmed within the Veolia landfill site shows a large motorised pump extracting untreated leachate from a containment pool

In a fourth video, a worker in a Veolia uniform is seen adjusting the pump as the same process occurs

A source with inside knowledge of the site’s operation, who asked to remain anonymous, told Global Witness the videos show a regular practice at the site. Ordered by supervisors, it occurs throughout the year but most frequently during the rainy season, when it can be carried out multiple times a week, according to the source.

Veolia did not dispute the location of the leachate dumping. It did question whether the topography of the area would allow for contamination of watercourses or wetlands, a position flatly contradicted by evidence filed in previous court cases.

The firm told Global Witness: “We want to make it absolutely clear that our management has never authorised or instructed anyone to engage in the practices allegedly depicted in the video material provided.”

It said that it had filed a criminal complaint with the local Prosecutor’s Office, and also detailed “extraordinary measures” taken “to ensure environmental compliance at the site.”

These included “regular internal verifications exceeding regulatory requirements,” the implementation of additional security and training measures, and a request for additional inspections by the environmental authority.

Samples processed by nationally certified laboratories have always demonstrated heavy metals levels within the maximum permissible limits, Veolia said, adding that there are no pending environmental sanctions in respect of the landfill.

Interwoven wetlands

Once Veolia’s untreated leachate leaves the landfill site, the zone’s interconnected hydrography means it is likely to contaminate a large area, environmental experts told Global Witness.

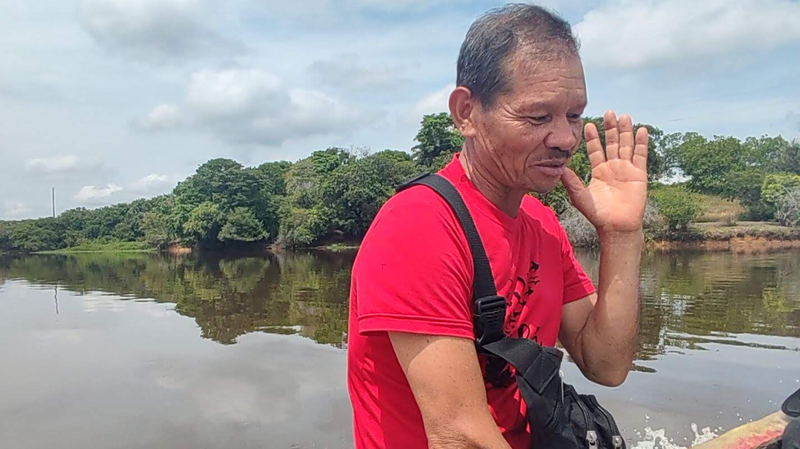

“The leachate flows into a stream called Caño Moncholo, which flows into another named Quebrada El Zarzal,” said Leonardo Granados, director of San Silvestre Green, which has fought a long legal battle against the landfill.

El Zarzal then flows into Ciénaga San Silvestre, a freshwater swamp which sits just north of Barrancabermeja and provides drinking water to 300,000 people.

The leachate therefore contaminates this entire hydrographic line, not only San Silvestre but all the previous tributaries too

Other heavy metals present at high concentrations in the samples tested by Global Witness include chromium, associated with cancer and liver and kidney damage; lead, linked to nerve and brain damage; and manganese, which can damage lungs.

“These are some of the most dangerous heavy metals,” said Flaviano Bianchini.

“Mercury accumulates easily into plant, animal and fish life, and if people eat this it can be highly toxic.

“It is very abundant in some of the samples which is undoubtedly a cause for concern, including for pregnancy.”

Colombia is a signatory to the Minamata Convention, which aims to reduce and eliminate mercury contamination globally. The UK government, also a signatory, notes “particular concerns” about mercury’s “harmful effects on unborn children and infants.”

While Colombia doesn’t have a legal framework for permissible limits of pollutants in sediment, Canada has a clear set of scientific guidelines to determine risks. Known as “sediment quality guidelines for the protection of aquatic life,” these establish the precise concentrations at which mercury contamination poses a threat to freshwater life.

If mercury concentrations are below 0.17mg/kg, they are “rarely” associated with negative impacts, the guidelines state. If mercury concentrations are above 0.486mg/kg, on the other hand, they are “frequently associated with adverse biological effects.”

The sediment sample taken closest to the Veolia landfill contained 4.25mg/kg: 25 times higher than mercury concentrations considered reliably safe in Canada, and nine times above levels at which the element is “frequently” associated with negative effects.

All four samples commissioned by Global Witness were at least twice the higher “probable effect level”, indicating a strong possibility that mercury contamination is impacting the environment around the landfill site.

What is the source?

Veolia denied that the leachate dumping seen in the videos could be the source of the heavy metal contamination found in Global Witness’s sediment tests.

To support this, they shared testing results from their own monitoring of the site, covering “surface water, groundwater, soil and leachates at different stages of the process.”

Conducted twice-yearly “by an independent and accredited laboratory in Colombia”, these tests detected no presence of mercury, and low – although measurable – levels of chromium, lead and manganese.

“Proximity does not mean cause, as the area in question has been subject to years of intervention by different types of industries and anthropic activities,” Veolia told Global Witness.

Global Witness had not, they said, set out to study all possible causes of pollution in the test area, and the research was marked by assumption and speculation. No previous data examining heavy metal contamination levels at the exact same locations exists, the firm said.

We shared Veolia's views and evidence with Flaviano Bianchini at Source International and asked whether and in what ways it contradicted the film and test data we had obtained, and if it changed any of his views on what we had originally shown him.

He disputed Veolia’s claim that it proved the landfill could not be the source of the heavy metal contamination seen in the samples.

“Mercury is very volatile … and difficult to find in water,” Bianchini said. “It is normally found either in sediment or in biota (plants and fish).”

All six soil sampling points used by Veolia were located on the far side of the site to the leachate dumping, separated from it by a hill.

Moreover, Bianchini emphasised that soil is not the same as sediment, which is deposited by the flow of water. Accordingly, there is no possible hydrological connection between Veolia’s soil sample points and the location of the leachate dumping.

In contrast, Global Witness’s sample locations were specifically chosen to detect any contamination that could have been caused by the leachate dumping seen in the videos.

This leachate enters the environment on an incline which slopes down to an area of wetland beyond the landfill site.

Caño Moncholo – the indirect tributary of Ciénaga San Silvestre highlighted by Leonardo Granados – then flows from this wetland past the west of the landfill.

Global Witness’s sediment samples were taken from four points in the downstream flow of Caño Moncholo.

Finally, Bianchini said that the leachate testing results shared by Veolia were too infrequent to determine if leachate from the site is responsible for the heavy metal contamination found beside it.

“Monitoring results are only provided for every six months, which is a very long time between tests. I would expect one monitoring test per week, or at least two per month,” he said.

“Analyzing only water, they are essentially providing a snapshot of only two days per year,” he added.

“There is no way to know what has happened in between the six months ... With only two analyses per year, it is very easy for a company to just avoid pollution (for example by stopping activities) for two days per year.”

Taking into account the evidence provided by Veolia, Bianchini said he still considered the landfill the most likely source of the mercury contamination found by Global Witness.

It is not suggested that Veolia has sought to distort or undermine any test data it is obliged to report for Colombian environmental monitoring.

Vultures and rats

One community neighbouring the landfill has endured its impacts for almost a decade. Himelda Arias, 68, had lived in the village of Patio Bonito for 30 years when the landfill began operating barely 500 metres from her door.

“The smell was so terrible you wanted to dig a hole and bury yourself under the earth,” she told Global Witness in her home on a small hill directly overlooking the landfill.

“Then it killed all the fish, it contaminated our water.”

Patio Bonito residents put up a fierce fight demanding the closure of the landfill. With the support of Leonardo Granados, they won a significant victory in Colombia’s Constitutional Court, which ruled that original owner Rediba had violated “the rights to health, a healthy environment and public health” of the residents.

The ruling directed Rediba to improve its management of the site. It stopped short, however, of ordering the landfill’s closure. Dispirited, numerous residents left the village. Among them was former community leader Graciela Rojas, who received death threats following her activism against the landfill.

Just as people are displaced due to violence, people are also displaced due to pollution, and that’s what happened to me

Despite managing the site for the past five years, Veolia has failed to implement several elements of the Constitutional Court order.

Those who have remained in Patio Bonito are still reliant on twice-weekly municipal tanker truck deliveries for drinking water, as Veolia has failed to provide any alternative solution.

Community members cannot fish in the surrounding wetlands, as they previously did for decades. They remain plagued by the odours, pests and health implications that come with living next door to the landfill.

“There are rats on one side, flies and cockroaches on the other, vultures in the trees,” Arias told Global Witness. “People are still getting ill, with colds, aches, sore throats.”

“I wish it would go, that all this would be done with,” she sighed, piling up homemade tamales on a wooden table in the porch of her home.

Veolia told Global Witness that it has “established a good working relationship and communications with the Patio Bonito community,” adding that five of its employees live in the village.

Endangering ecosystems

As well as endangering public health, contamination has over time also impacted surrounding ecosystems. This includes Ciénaga San Silvestre, a major source of fish and drinking water for Barrancabermeja residents.

Dotted with green islands and fringed by verdant vegetation, San Silvestre is rich in tropical flora and fauna. White and grey herons wing across its sparkling surface, manatees and caimans push through its depths, and howler and capuchin monkeys swing through the trees that crowd its shoreline.

A maze of streams and marshlands connect it with the other lakes and waterways that make up these sweltering wetlands, themselves a part of the “Jaguar Corridor”, an international network of protected areas linking big cat populations in Central America with those in the Amazon.

For generations, fishermen and women have made a living from these sun-soaked waters, home to species found on almost every menu in Barrancabermeja – mojarra, bagre, blanquillo, and, most traditionally, bocachico, prized for its fatty, flavourful flesh.

In recent years, however, this catch has diminished considerably.

“We see fewer of the species that used to be here in abundance,” says Wilson Diaz, a representative of the Magdalena Medio fishing union.

“Before we went out fishing and we could make an average of 100,000 Pesos a day, sometimes 200, 300. Not now. You start fishing and if you make 20,000 Pesos, that is a lot.”

Fishermen from a neighbouring swamp named El Llanito, directly connected to San Silvestre by a broad stream, told Global Witness there were areas they could no longer fish due to contamination. Sometimes they’d catch fish that carried a strong chemical or putrid odour and would be forced to throw them back.

“It’s harder to sell the fish that we do catch, so we’re making less, sometimes we can’t make anything at all,” says Samuel Arengo, Vice President of the Llanito Fisher and Farmer Association (APALL).

The landfill is not the sole source of contamination of the wetlands. Barrancabermeja is at the heart of Colombia’s oil industry. The chimneys and flares of a giant refinery dominate the city’s western skyline, operated by Colombia’s largest oil company, Ecopetrol. For decades, pollution from the industry has impacted the wetlands that neighbour it.

But the situation deteriorated with the arrival of the landfill, Diaz explained.

“Now at the bottom of the lake you see long worms swimming in the water, and we sometimes find worms inside the fish,” he said. “We didn’t see this before the landfill.”

Neither Global Witness nor local NGOs yet have data linking the declining condition of San Silvestre with Veolia's plant, but the testimony of multiple local people suggests a possible correlation.

Almost three decades of data leaked from Ecopetrol and made public in a recent investigation by the BBC showed no cases of oil contamination near the landfill, with impacts concentrated more than 15km downstream of Veolia’s site.

Like many of the people interviewed in this piece, Diaz has received threats for voicing concerns about contamination.

Colombia is the most dangerous place in the world to defend the environment, following Global Witness’s own analysis – 79 land and environmental defenders were killed in Colombia in 2023, 40% of all cases documented worldwide.

A 2022 study conducted by the Special Jurisdiction for Peace – a transitional justice mechanism in Colombia – concluded that Santander, the department containing Barrancabermeja and San Silvestre, is the most dangerous region in Colombia for environmental defenders.

Global Witness spoke with medical, environmental, community and human rights activists who’d been threatened after raising concerns about the landfill during its ownership by Rediba.

Dr Blanco now lives in exile after being named in a pamphlet published by a paramilitary group, while Leonardo Granados travels with constant security.

The threats come from “armed groups who have maintained a historic relationship with the business sector in the region,” explained Ivan Madero, director of CREDHOS, a Barrancabermeja-based human rights group.

While there is no suggestion that Veolia plays any part in sustaining paramilitary violence in Colombia, Madero argues that any owner of the landfill, or the refinery, benefits from these threats.

“When leaders are forced to move due to threats, they are silenced, and the investigations they were demanding are stalled,” he said.

Veolia told Global Witness that it “strongly condemns the use of violence to threaten community leaders.”

It also dismissed “the preposterous claim that it benefits in any way from paramilitary violence in Colombia.”

The Colombian authorities must end the impunity around the landfill and better investigate the recent contamination allegations. It must also ultimately ensure the landfill itself is closed and moved to a location where it does not risk contaminating the wetland environment nor the city’s drinking water.

Veolia itself should support efforts to hold its staff accountable for authorising the leachate dumping that the videos appear to show. It should use its wealth and expertise to ensure this damaging landfill is finally closed, and a sustainable solution found for Barrancabermeja’s waste.

The role of the EU

While Veolia's legal obligations in Colombia remain firmly intact, this case underscores the urgent need for mandatory international legislation to hold companies responsible for preventing and addressing human rights violations and environmental damage.

The EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) was designed for this purpose. While it officially entered into force last year, the European Commission has recently re-opened the CSDDD and introduced far reaching amendments to it and other sustainability laws.

If these amendments are approved as proposed it would significantly weaken the law, diminishing its impact and curtailing obligations to address human rights and environmental risks in companies’ value chains.

Claire Bright, Associate Professor of Private Law at NOVA School of Law, explains that the original CSDDD, as adopted in 2024, "provides that companies must conduct human rights and environmental due diligence.

"This means that companies must put in place processes allowing them to regularly identify and assess the risks that their operations and those of their business partners pose for human rights and the environment.”

Nicolas Bueno, Professor of International and European Law at UniDistance Suisse, adds that “under the CSDDD, respecting human rights includes avoiding causing environmental degradation, such as harmful soil change, water pollution, harmful emissions, excessive water consumption or degradation in a way that would infringe the human rights to an adequate standard of living and to health.

"And if companies fail to meet their human rights and environmental due diligence obligations in their operations and across their value chains, they may be held liable and required to compensate the damage caused to affected individuals.”

The proposed amendments would weaken the rights of victims to seek justice under the CSDDD. If adopted, decisions on whether victims can take companies to court in the EU would be left to the discretion of individual EU member states.

This threatens to remove a key principle of the original CSDDD, which allows victims to sue companies under EU law, rather than the law of the country where the harm occurred – where powerful corporations can take advantage of fragile institutions to evade accountability.

If the EU Commission's proposal goes ahead in its current form, victims will be left with limited or no effective means of pursuing their rights in EU courts. We therefore call on Members of the European Parliament and EU Member States to reject the weakening of the CSDDD and to reinstate the CSDDD as adopted in 2024.