Tools to silence land and environmental defenders globally are on the rise. In Asia, detentions and criminalisation of defenders are becoming increasingly common. Patterns in the types of laws being used are starting to emerge. Here we analyse these and look at how governments weaponise laws to detain defenders in the region.

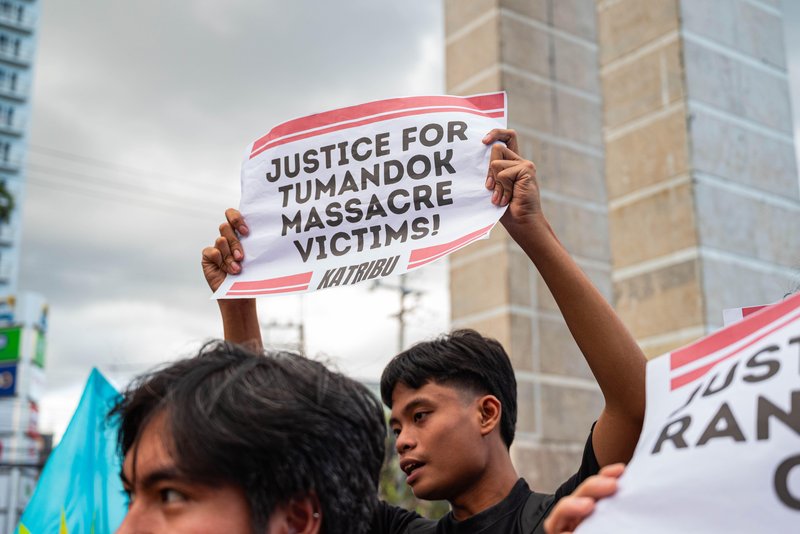

Around 4am on 30 December 2020, security forces stormed a cluster of villages near two megadam projects in the central Philippines. Nine leaders of the Indigenous Tumandok people were gunned down in their homes. Sixteen others were arrested and charged with rebellion.

This murderous raid followed a Tumandok protest against the dams two weeks earlier. The day of the protest, the leaders were accused of being communist rebels – a practice known as “red-tagging”.

The protest was the latest instalment in the Tumandok’s lengthy struggle against the megadam projects, which threaten to submerge their ancestral lands and uproot their way of life. Nearly five years later, the community is still fighting for justice.

Perverting justice: The criminalisation of land and environmental defenders in Asia

Download Resource

A protester holds up a sign which calls for justice among the Tumandok Massacre. ZUMA Press, Inc. / Alamy Live News

Criminalised for taking a stand

The Tumandok community’s experience of being treated like criminals for speaking out is far from unique.

Across the world, people making a stand to protect their land and environment are being silenced by criminalisation – a method used by powerful state and corporate interests to shut down opposition to major agribusiness, mining and commercial projects.

This new Global Witness analysis explores the rising tide of criminalisation in Asia. It zooms in on four countries where the tactic is particularly prevalent – the Philippines, Indonesia, India and Vietnam – to illustrate a trend that is truly global in scope.

Criminalisation: A definition

Criminalisation is the use of threatened or actual legal action by government officials and private actors to stigmatise, discredit and silence land and environmental defenders.

Sometimes new laws have been designed to stifle free speech and expression, including the right to protest. Other times, existing laws are weaponised against defenders.

The ensuing legal battles are rarely a fair fight. Expensive lawyers representing government and corporate interests take on farmers and Indigenous leaders in remote communities who may not know their rights or be able to afford a lawyer.

Defenders are publicly demonised as criminals and instigators, and face the trauma of incarceration. As a result, criminalisation sends a chilling warning to defenders and their communities to think twice before speaking up against powerful interests.

Our research found that 341 land and environmental defenders were detained or arrested – across 344 separate incidents[i] between 2018 and 2024 in these four countries.

Government and big business deployed a range of tactics to put defenders behind bars, using the law and judicial system to:

- Grab the lands of small-scale farmers and Indigenous Peoples

- Silence peaceful protest and dissent

- Charge defenders as enemies of the state – as terrorists, communists or insurgents

- Keep people who speak out in extended pre-trial detention or imprison them on trumped-up charges

Criminalisation in numbers: Mapping a growing trend

341 defenders were detained in 344 incidents between 2018 and 2024 in the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam and India.

Demographics:

- Men accounted for 73% of arrests or detentions, women 27%, where gender was reported

- 88 incidents of Indigenous Peoples being arrested were recorded – 26% of the total number of cases in which defender characteristics were reported.

- Farmers accounted for 88 (26%) of the cases in which defender characteristics were reported

Criminalised for opposing land grabs

Across Indonesia, India, Vietnam and the Philippines, most recorded arrests or detentions (59%) were linked to the struggle for land.

In Indonesia, 106 conflicts are raging over natural resources, with land disputes affecting more than 1 million people. These conflicts often involve government, police and military forces seizing land from families for the sake of corporate profit.

Agribusinesses in Indonesia are protected by a law that criminalises crop cultivation on public or plantation land. This law is used to imprison defenders involved in land disputes with large corporations, with a maximum prison sentence of four years.

We recorded 10 cases of defenders being arrested and imprisoned in Indonesia between 2018 and 2024 for "illegal cultivation", or "illegal cuttings."

In Indonesia’s Bengkulu Province, Human Rights Monitor reported the arrest of more than 40 farmers charged with stealing palm fruit over a six-month period from agribusiness PT Daria Darma Pratama.[ii]

These "thefts" took place on disputed land that small-scale farmers allege had been taken from them without adequate compensation.

An aerial view of palm oil plantations in Merang, Indonesia. Ulet Ifansasti / Getty Images

Case study: Eco-City

Rempang Island, part of Indonesia’s Riau Archipelago, is the scene of an escalating conflict between corporate interests, traditional land ownership and the right to peaceful protest.

In a project named Eco-City, Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo plans to make Rempang Island a hub of economic development.

The project has allocated 40% of the island’s land for business activity, with the rest to be kept as protected forest. This has put all 7,500 of Rempang’s current inhabitants – who had no say in the decision-making process – at risk of being forced to leave the island.

Indigenous and fishing communities, generations of whom have lived on the island for centuries, could lose their way of life and the land where their families are buried.

In response, many Rempang citizens took to the streets to protest. These descended into violence and led to arrests by the authorities. According to the YLBHI, 50 environmental defenders had been arrested as of 2023 for protesting against land grabs associated with Eco-City.

Other defenders have also been criminalised for speaking out. One was charged with “spreading hate” after sending a WhatsApp message telling people not to accept the goods the authorities were offering to build support for the project.

As of November 2024, “surprise” house demolitions were carried out despite communities rejecting evictions, and defenders were still being harassed.

Eco-City is what is known as a “National Strategic Project (NSP)”, an initiative launched by President Widodo in 2016 which commits the government to complete major development projects. It also allows private corporations to acquire land more easily.

To push NSPs like Eco-City ahead as quickly as possible, businesses and the state have used criminalisation to silence and stigmatise defenders opposing the damage inflicted by projects on the environment and local communities.

YLBHI has identified 43 criminal cases connected with resource conflict or NSPs affecting 212 environmental defenders.

The Indonesian government told Global Witness it had a “firm commitment to upholding the right to a good and healthy environment.” It cited the introduction of a new regulation in 2024 aimed at safeguarding environmental defenders against legal charges.

Indonesian mounted riot police pursue protesters following demonstrations in Jakarta. Ed Wray / Getty Images

Criminalised for peaceful protest

Nearly a quarter of all documented detentions in which a charge was reportedly made were linked to protests. Almost all of these cases – 60 out of 67 – were in India.

Protestors in India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam, particularly those opposing lucrative development projects and agribusiness, are often met with violence and arrest.

Sometimes protesters were arrested without charge – a tactic intended to intimidate and silence protest. In 2020, three student journalists merely covering a protest against sand mining in Indonesia were reportedly arrested and held overnight without charge.

Case study: Criminalised for opposing coal mining

In July 2022, campaigning by one of India’s most successful environmental movements, #SaveHasdeo, culminated in the cancellation of 21 planned coal-mining operations by the state legislature. It also led to the creation of a mining-free zone called the Lemru Elephant Reserve.

The decision helped to protect 445,000 acres of pristine forest in the Hasdeo region, known as the ”Lungs of Central India”. This accomplishment earned Alok Shukla, a movement leader, the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize.

And yet defenders in Hasdeo are still harassed and criminalised by the authorities for standing in the way of the region’s socially and ecologically devastating coal-mining operations.

When deforestation began in 2022 ahead of proposed mining, protesters were threatened by police and detained in their homes.

In another incident, a criminal complaint was lodged against 10 activists by an employee of mining company Adani alleging “fraud, rioting, unlawful assembly, intent to cause hurt and criminal intimidation, among others,” according to a media report.

In 2023, the Adani Group reportedly continued clearing part of the forest near the village of Hariharpur to prepare it for mining, despite legal challenges alleging it had forged community consent. Reports suggest that this deforestation work was overseen by members of the Central Reserve Police Force.

Ramlal Kariyam, Jainandan Porte and Thakur Ram – leaders of a group called the Committee for the Struggle to Save the Hasdeo Forest – were arrested while trying to prevent the deforestation and detained for several days.

During this time, Hariharpur village became a “virtual garrison,” according to Alok Shukla, as police forced people to stay in their homes while at least 20,000 trees were felled.

To this day, defenders of the Hasdeo work to protect its beautiful forests despite the threats they face.

Workers carry coal at a coal yard near a mine on November 23, 2021 in Sonbhadra, Uttar Pradesh India. Ritesh Shukla / Getty Images

Criminalised for speaking out

All four countries have criminal defamation laws that are weaponised against defenders as a tool to stifle dissent.

In the Philippines, “cyber libel” – unlawfully hurting the reputations of others “through a computer system” – is a criminal offence, punishable by both imprisonment and fines. It has been applied harshly against journalists.

Kimberlie Ngabit-Quitasol is the editor-in-chief of Northern District, a newspaper covering Indigenous Peoples’ issues and human rights in the Philippines’ Cordillera region. In September 2020, she was charged with cyber libel for reporting on military threats against the human rights organisation Karapatan.

Her case is among a growing number of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs) documented in the Philippines and wider region.

One in five cases in which charges were reportedly made across the four countries involved at least one charge linked to speech.

For example, Daniel Frits Maurits Tangkilisan was sentenced to seven months in prison in Indonesia for “hate speech” after posting on Facebook about shrimp farms illegally operating in protected waters.

In Vietnam, the government often uses sweeping laws that criminalise free speech. This includes Article 331 of the 2015 penal code, which outlaws “abuses” of free speech. Article 117 criminalises speech that “opposes” or “contains distorted information” about the state.

Violators face a minimum of five years in prison – rising to a maximum of 20 years for serious cases. Defenders can be jailed for five years simply for “making preparation” to commit an offence. These laws can be used against anyone who speaks out against state-sponsored land grabs, large-scale development projects or damage to the environment.

In 2021, environmental activist Đinh Thị Thu Thủy was sentenced to seven years in prison under article 117, seemingly for social media posts advocating for a cleaner environment and other human rights.

Articles 117 and 331 of the penal code were used in nearly two-thirds of all arrests of land and environmental defenders in Vietnam.

Criminalised as "enemies of the state"

In each of the four countries, defenders are vilified as enemies of the state. They are often accused of terrorism, insurgency, sedition or other forms of anti-state violence.

Of cases with reported charges, 14% involved some type of crime against the state, while 7% involved a charge under anti-terror legislation.

Using the military and counter-insurgency measures

The military, particularly in India and the Philippines, is involved in criminalising people who defend their land.

The military was present at 27% of the arrests documented by Forum-Asia – all of them in the Philippines. Around two-thirds of all cases of defender arrests in the Philippines involved the military.

The militaries of both India and the Philippines are particularly associated with cases where defenders are accused of terrorism or rebellion. Counter-insurgency narratives are frequently weaponised against defenders in these two countries.

The Philippine government often accuses environmental defenders of being sympathisers of a decades-long Maoist insurgency. Civil society groups say counter-insurgency efforts are used to justify deploying the military to crush opposition to large-scale development projects.

Similarly in India, security force involvement – instituted with the purported aim of fighting left-wing extremism – exacerbates land grabs and criminalisation, even though arrests are carried out by the police.

In central India’s Bastar district in late 2023 to early 2024, for example, at least five defenders protesting mining projects protected by security forces were arrested and detained for their peaceful activism.

Branded communists by red-tagging

One of the most common and serious forms of criminalisation in the Philippines is the branding of defenders as communists or communist terrorists – a practice known as “red-tagging”.

Red-tagging can start with the posting of anonymous lists or the distribution of pamphlets labelling defenders as communists, before moving into more public denunciations of individuals as communists by government and military officials. This then escalates in some cases into harassment, violence and criminal punishment.

The use of red-tagging seems to be increasing. In June 2023, Human Rights Watch reported that the red-tagging of human rights defenders was noticeably higher during President Marcos Jr’s first year in office than during the previous Duterte administration.

A counter-insurgency taskforce established by President Rodrigo Duterte in 2018 has become infamous for its red-tagging practices.

The National Task Force to End the Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) has broad powers with little oversight, due process, or checks. The NTF-ELCAC red-tags environmental defenders through both official press releases and social media posts.

Defenders Jhed Tamano and Jonila Castro were recently red-tagged by the NTF-ELCAC, leading to their abduction by the Philippine military and subsequent legal harassment. UN experts have called for the taskforce to be abolished.

Environmental defenders Jhed Tamanano and Jonila Castro (pictured) were abducted by the military after being red-tagged by authorities

Criminalised as terrorists

Defenders red-tagged in the Philippines can often end up being officially designated as “terrorists”, with little to no due process. Of all the terrorism cases against defenders analysed in this report, 45% were in the Philippines.

Under the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020, the Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC) has the unilateral power to designate an individual or organisation as terrorist, so long as it determines there is “probable cause.”

Being designated a terrorist puts people at risk of extra-judicial killing, pre-trial detention, criminal charges, freezing of assets and government surveillance. In 2023, multiple UN human rights experts wrote to the Philippine government after identifying 24 cases of defenders being harmed in the name of anti-terrorism.

The Anti-Money Laundering Council can order a freeze on the assets of anyone designated a terrorist. The assets of defender Jennifer Awingan-Taggaoa, an Indigenous leader with the Cordillera People’s Alliance, were frozen in this way. As a result, she lost the small general store she ran, and her husband struggled to receive his salary as a university professor.

The Anti-Terrorism Act also allows police and military officials to imprison individuals for up to 24 days without charge. It enables the government to conduct surveillance on people designated as terrorists, adding to the culture of fear and repression faced by criminalised defenders and their families.

Anti-terrorism laws are frequently used against defenders in India too. The Unlawful Activities and Prevention Act (UAPA) is open to abuse by officials, who use it to silence criticism.

Designated ”terrorists” can be arrested and detained without the usual need for evidence, allowing the government to punish defenders without having to find them guilty in a court of law.

The bar for bail is also set much higher, making it easier for authorities to keep defenders in pre-trial detention for long periods.

UAPA’s definition of “terrorist” is so vague it can be applied to include people who express “disaffection with India” through public protest – a clear violation of the right to freedom of expression.

Indeed, under the UAPA, authorities blocked the website associated with Greta Thunberg's movement, Fridays For Future India, finding it “objectionable” and a part of an “unlawful or terrorist act.”

We have recorded nine defenders arrested and detained under the UAPA.

Damodar Turi, a campaigner against forced land acquisition, was arrested in 2018 under UAPA on the trumped-up charge that he was a member of a recently banned union. After the arrest he was kept in solitary confinement for three months without being allowed a trial.

Using weapons charges

Nearly a third of all cases with reported charges included at least one weapons charge.

Extreme measures used by the Philippine police and military to respond to suspected weapons and terror offences can result in lethal violence.

In an incident now referred to as “Bloody Sunday”, nine defenders were killed and six more were arrested during police and military raids in the Calabarzon region using a search warrant covering the illegal possession of explosives.

The Philippine government has been accused of routinely planting weapons and ammunition in the homes of defenders. Defenders who have been red-tagged often make such allegations.

Of all cases that recorded charges in the Philippines, 49% involved an illegal weapons or ammunitions charge.

Demonstrators take part in a protest against climate change as part of the Fridays For Future Movement on September 25, 2020 in New Delhi, India. Mayank Makhija / NurPhoto

Trumped-up charges, pre-trial detention and other due process violations

Trumped-up charges of violent crime and terrorism are common tactics used to both criminalise and stigmatise defenders.

More than a third of all cases that reported charges involved at least one charge relating to violent crime, such as murder or assault.

Land and environmental defenders in the Philippines are arrested, detained and charged under regular aspects of the Philippine penal code.

Often these charges either have no basis in evidence or are implausible. In many cases, they are clearly trumped-up charges to silence and harass defenders.

They are often serious charges – including for murder, kidnapping and rebellion – that can be used to discredit the defenders’ legitimacy and lead to lengthy imprisonment.

In India, First Information Reports (FIRs) – documents written by police when they believe a serious offence has been committed – are used to intimidate and criminalise defenders.

Importantly, the police can arrest an individual listed on a FIR at any time without first obtaining a warrant. It is quite common for a FIR to accuse a defender of a whole list of serious crimes, such as murder, kidnapping or rape, for which there is little to no evidence.

In May 2022, for example, five defenders opposing clay mining in Odisha’s Koraput district were arrested under two FIRs that contained more than 10 crimes apiece, including attempted murder and kidnapping. Rights groups say the defenders arrested were not even present at the alleged incident.

FIRs can list groups of people without identifying individuals, serving to silence whole movements. In Gadchiroli, Maharashtra, a peaceful protest opposing mining permits was interrupted by hundreds of police officers who arrested six defenders. Following the arrests, a FIR was registered against nine named individuals, and 100 unnamed protesters.

The Vietnamese government has used tax-evasion law to imprison high-profile NGO leaders and silence them. We recorded five such cases.

These tax evasion cases are considered by many commentators to be complete shams, used to criminalise activists and NGOs that receive foreign funding.

Nguy Thi Khanh, founder of the Green Innovation and Development Centre (Green ID), was detained without charge for almost a month and then sentenced to 24 months in prison for not paying taxes on personal income, including money she received for winning the Goldman prize.

Analysis by the 88 Project shows that criminal prosecution and detention for personal income tax irregularities are exceedingly rare in Vietnam, only accounting for about 1% of all tax convictions.

This strongly suggests the prosecution of Nguy Thi Kanh and other environmental defenders for tax evasion in Vietnam is based on trumped-up charges used to silence dissent.

Retribution against defenders

Our research found that pre-trial detention and other due process violations are a common form of retribution against defenders. In 81% of cases where we were able to determine the length of detention, defenders were kept in pre-trial detention for a week or longer.

The long sentences imposed on defenders in Vietnam often involve a myriad of due process violations. Vietnam is a signatory to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), requiring it to uphold basic due process standards. But Vietnam appears to have violated this obligation by:

- Imposing mandatory pre-trial detention on defenders

- Keeping them incommunicado

- Detaining them without charge

- Instituting closed trials

- Denying them access to legal representation

Article 9 of the ICCPR states that imprisoned individuals “shall be entitled to trial within a reasonable time or to release.”

But Vietnam consistently keeps criminalised defenders in pre-trial detention for months, sometimes years, at a time. Often they don’t have access to lawyers or their families during this time.

A report by the 88 Project highlights the widespread use of pre-trial detention against human rights defenders in Vietnam. It states that “[o]f the activists arrested in 2018 and 2019, seven people were as of September 2020 still in pre-trial detention. All have been detained incommunicado for eight months or longer.”

Charged defenders in Vietnam are also often denied a proper trial. Sometimes their trials last just a few hours before a guilty verdict is passed. Proceedings are often closed to family, friends and the media.

Vu Thi Kim Hoang, for example, who was arrested after reporting on a land dispute, was sentenced to two years in prison following a trial in which police pressured her to attend without her lawyer.

In India, again in violation of international law, extensive pre-trial detention is also a common experience for criminalised defenders. The expense and difficulty of hiring a lawyer, and the marginalised and rural nature of many of the communities who are affected by land grabbing, means it is common for defenders to face long periods of pre-trial detention, despite laws prohibiting it.

Conclusion

This report focuses on four countries where criminalisation is an increasingly pervasive tactic to silence protest and dissent.

Our research using Forum-Asia data found that 341 defenders were arrested and detained between 2018-2024 for defending their land or the environment in India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

But this tells only part of the story of criminalisation in these four countries. Many more have been detained while protesting, threatened by trumped-up charges, or faced SLAPPs for their work.

The governments of India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam must stop using the tactic of criminalisation to silence defenders. Instead, they must work to:

- Increase civic space

- Demilitarise civilian areas

- Increase legal protection for defenders

- Repeal and amend laws used to unjustly target them

It is also essential these governments respect and protect traditional, ancestral and Indigenous land rights.

The use of criminalisation to silence, threaten and stigmatise defenders is by no means limited to the countries in this report. It is a growing problem worldwide.

It is time for that to change. As the climate crisis worsens, the world needs defenders more than ever. It is vital they are safe to do their essential work.

Recommendations

India

- Remove the UAPA’s ambiguous language, which is used to keep defenders in extended pre-trial detention.

- Enhance and specify the burden of proof under which environmental defenders can be arrested and kept in pre-trial detention.

- Ensure due process is implemented for the arrest and imprisonment of environmental defenders as required by international law.

- End the use of government security forces to protect the operations of extractive industries.

Vietnam

- Immediately release all those incarcerated for legitimate and peaceful acts of expression.

- Stop weaponising the tax code to imprison defenders and release those defenders who have been imprisoned unjustly under it.

- Repeal articles 331 and 117 of the penal code, which punish legitimate forms of speech.

- Ensure defendants in criminal trials have access to proper due process as required under international law, which includes providing access to a lawyer, ending close-door and mobile trials and not holding defendants in incognito pre-trial detention.

The Philippines

- Disband the ATC or implement clear due process requirements, transparency and the possibility of appeal.

- Increase oversight of military and police misconduct.

- Withdraw the military from civilian policing duties.

- Abolish the NTF-ELCAC.

- Repeal laws that criminalise defamation and cyber libel, and ensure that any civil defamation cases include truth as a complete defence.

Indonesia

- Respect traditional and ancestral land rights, and end evictions for the purpose of National Strategic Projects.

- Amend mining and plantation laws to include protections for traditional land rights and implement strict free prior and informed consent in line with ILO 169.

- Enforce anti-corruption measures.

- Revise the Criminal Procedure Law to ensure it is in line with Indonesian human rights regulations. Create checks on police investigator power to prevent criminalisation of defenders.

- Revoke the Job Creation Law, which eliminates many guarantees of community and environmental protection.

Other countries

- Embassies from countries around the world can help mitigate the damaging effects of criminalisation by attending the trials of criminalised defenders and putting out public statements to support them.

Perverting justice: The criminalisation of land and environmental defenders in Asia

Download ResourceMethodology

All data on criminalisation in this report sourced from the Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (Forum-Asia).

The cases we included in the data conform to Global Witness’s definition of "land and environmental defenders". That is “people who take a stand and carry out peaceful action against the unjust, discriminatory, corrupt or damaging exploitation of natural resources or the environment.” This definition of land and environmental defenders encompasses a broad range of actors: people defending their land and way of life from land grabs; professionals such as journalists and lawyers; protesters; and climate activists, just to name a few.

For this report, we analysed cases of arrest and detention of more than 12 hours that occurred between January 2018 and December 2023. Arrest and detention is just one form of criminalisation. Many other instances of criminalisation occurred against defenders during this period, which are not reflected in the data presented, but can be found in the Forum-Asia database.

Information on criminalisation processes has been generously provided by the 88 Project, the London Story, Karapatan, Civicus, Forum-Asia, the Gecko Project, the India Justice Project and Yayasan Lembaga Bantuan Hukum Indonesia.

Notes

[i] Three defenders were detained twice during this period.

[ii] These arrests are not captured by the data in our analysis as we did not look at cases of mass arrest.