Executive summary

The Philippines, which consists of over 7,600 islands in the Pacific Ocean, is one of the countries most at-risk from climate change. Many communities are already feeling the impacts of more severe storms, rising sea levels are a looming threat, and the warming ocean is putting marine life at risk. The protection and restoration of coastal ecosystems could play a key role in tackling climate change, but in Manila Bay those ecosystems are in jeopardy.

The New Manila International Airport, a US$15 billion mega-development project, is the Philippine’s most expensive infrastructure project ever.

Philippine conglomerate San Miguel Corporation (San Miguel) is building and managing the airport project. San Miguel’s impact assessments for the project reveal a pattern of failures which have had damaging consequences for communities and the environment in Manila Bay.

Two Dutch companies are involved in the project – dredging giant Royal Boskalis Westminster N.V. (Boskalis) has signed a contract worth €1.5 billion to construct the first phase of the project. This was insured by the by the Dutch state via export credit agency Atradius Dutch State Business (Atradius DSB). They have also made statements celebrating its social and environmental credentials.

However, since the project was given the green light in September 2019, it has already displaced hundreds of families, destroyed climate-critical habitats and devastated wildlife.

Our new report shows that:

- Around 700 families stood to be evicted to make way for the airport, according to local communities – with around half reportedly receiving no compensation.iv Local communities that relied on a balanced environment in Manila Bay now struggle to catch enough fish for a healthy diet and sustainable income.

- Prior to being displaced, residents describe a botched and coercive consultation process. They say armed soldiers went door-to-door with San Miguel representatives to discuss plans for the new airport. Community members report feeling pressured to take the compensation offered and feeling scared of further threats from the military who remained in the area. San Miguel downplayed the presence in its second impact assessment, which said that it was to "secure the project area" and to "prevent outsiders from causing disruption."

- Approval for the airport was granted by the Philippine government without the required transparency and safeguards that are outlined in international corporate accountability standards and are needed to protect people and the environment. The plans used in the initial project consultation reveal that they contain no mention of an international airport, preventing communities assessing or contesting the project’s impacts.

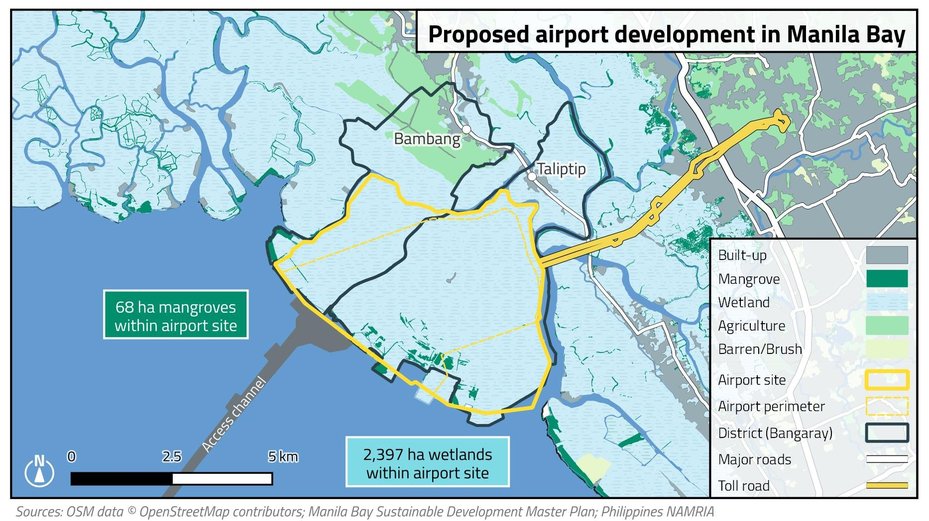

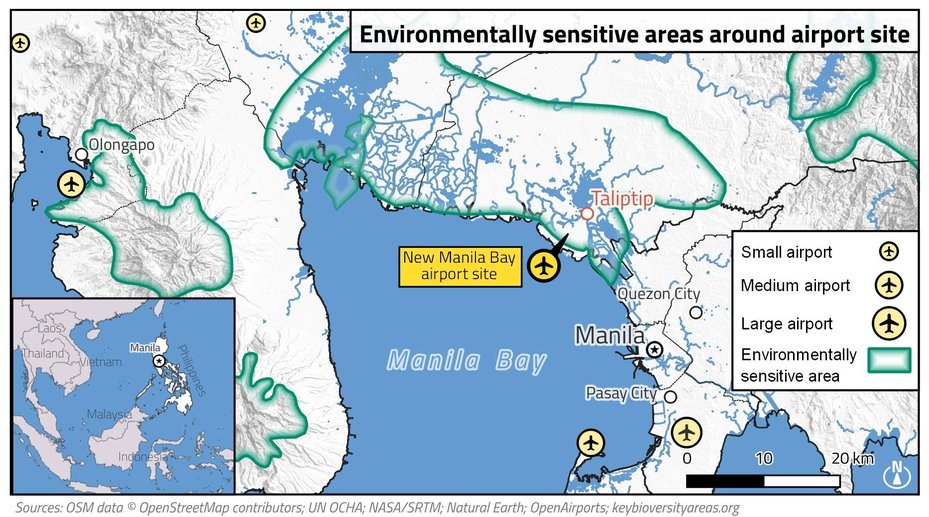

- The airport project site encroaches on a recommended "strict protection zone" identified in a sustainable development plan for Manila Bay, jointly developed by the Philippine and Netherlands governments. Under Philippine law, these protection zones should be closed to all human activity except for scientific studies, and ceremonial and non-extractive uses by Indigenous peoples. The plan recommended finding an alternative location for the project to avoid damage to the area’s natural habitats.

- Instead, complex coastal ecosystems have been destroyed to make way for the airport. The construction will disrupt the migratory route – known as the East Asian-Australasian Flyway – of more than 50 million waterbirds, including 36 globally threatened species, which journey northward from Southeast Asia and Australasia to seasonal breeding grounds.

- Hundreds of mangrove trees were apparently illegally cleared from the area according to a local government report in 2018. This occurred at the same time that San Miguel and another developer were purchasing land – the same land used in the airport development. With only a fraction of mangroves remaining in Manila Bay, these projects are helping to destroy the last frontiers of a fragile ecosystem. Mangroves contain the highest carbon density of all land ecosystems – so their loss has devastating consequences for the fight against climate change. They also help reduce coastal erosion and provide vital flood protection.

- The project’s climate impacts are expected to worsen over time. When completed, the new airport will cater for approximately 100 million passengers per year, making it one of the busiest airports by passenger traffic in the world. The aviation sector is a major and growing source of climate-wrecking greenhouse gas emissions.

Despite the growing list of harmful effects, San Miguel has steamed ahead with the airport project.

The EU is currently negotiating a new law – the Corporate Sustainable Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) – that could help prevent companies from profiting from human rights abuses, environmental destruction, and climate breakdown and allow affected communities to hold companies accountable for their business activities.

Global Witness calls on legislators to ensure that this new Directive puts people and the planet before profit.

Responding to Global Witness, San Miguel largely rejects Global Witness findings and states that its New Manila International Airport project adheres to international standards on environmental and social sustainability set out in the International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) Performance Standards and the Equator Principles.

The company states that it has complied with all the necessary procedural and documentary requirements required for its airport development as outlined in Philippine law. San Miguel received an Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC) for the project in 2021 in compliance with the Philippines Environmental Impact Statement system.

It maintains that a separate ECC was issued in 2019 to a separate company (that it later acquired) was different and for an unrelated "land development".

Responding to Global Witness, San Miguel only recognises the project displaced 359 households who were offered cash compensation or by paying for their resettlement. It stated that it was local government units who requested military and police presence during consultations and that that there are ‘no records of harassment’ recorded by the local government authorities.

San Miguel did not respond to allegations of specific cases of mangrove destruction in 2018 before the airport project commencement. It indicated however, that its project complies with all regulatory requirement relating to the care and preservation of mangroves located within and adjacent to the airport project.

Boskalis and Atradius DSB responded to Global Witness with details of their environmental and social impacts assessments and implementation plans. More detailed responses from the companies are included below.

This is Bulacan, Manila Bay, the gateway to the Philippines.

It is home to rich marine biodiversity, endangered migratory bird populations and coastal communities.

Now, warn scientists, the area’s delicate ecosystem and coastal communities are under threat from a new US $15 billion airport development. The New Manila International Airport – the Philippine’s most expensive infrastructure project in history – will cover an area seven and a half times the size of New York’s Central Park. When completed, it will cater for approximately 100 million passengers a year and be one of the busiest airports by passenger traffic globally.

The project is proposed, built, managed and operated by San Miguel – one of the largest conglomerates in the Philippines. Dutch company Royal Boskalis has signed a contract worth €1.5 billion to construct the first phase of the project. This was insured by the by the Dutch state via export credit agency Atradius DSB.

San Miguel’s bid for the international airport was given the green light by the Philippines government in September 2019, allowing construction to start at any time. The controversial decision came a year and a half after the Philippines and Netherlands joined forces to develop the Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan to ‘clean up, rehabilitate and preserve’ Manila Bay. Its report warns that to avoid damage to local communities, ecosystems and biodiversity, San Miguel should seek an alternate location for its airport project.

Instead, the project stood to evict approximately 700 families, according to communities in that area. Almost half reportedly received no compensation or relocation offer. Others felt intimidated to leave by the military, with residents reporting that San Miguel representatives were accompanied by armed soldiers on door-to-door visits to speak about the new airport. Residents now describe struggling to subsist and earn a living because of the disruption to their livelihoods. Responding to Global Witness, San Miguel stated that it was local government units which requested military and police presence during consultations.

A botched public consultation – which initially made no mention of an international airport – was part of a pattern of failures by San Miguel. Despite its current and potential harmful impacts, San Miguel, and its Dutch business partners have made statements celebrating the project’s environmental and social credentials.

Responding to Global Witness, San Miguel maintains that it obtained an Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC) for the airport project in 2021 in compliance with the Philippines Environmental Impact Statement system and provided details of its Environmental Impact Assessment procedure, adding that a public hearing was held and attended by stakeholders including the local communities. San Miguel also stated that an ECC issued in 2019 to a separate company (which it later acquired), was distinct to its own ECC and for unrelated ‘land development’.

Global Witness maintains that because San Miguel had already obtained authorisation from the Philippine government to begin work on an airport in September 2019, after which point it states that it carried out various consultations on its airport project, it was and necessarily would have been impossible to conduct valid consultations or environmental assessments with affected communities, who were unaware of the intended purpose of the project. In a second impact assessment completed by San Miguel in 2021, the company includes an earlier public consultation for a ‘land development’ in the same area as part of stakeholder engagement activities undertaken. The presentation, seen by Global Witness, makes no reference to a future airport development expressly.

The project’s environmental costs are already significant. Hundreds of mangrove trees, which not only absorb and store climate-wrecking carbon dioxide but also form natural flood barriers, have been cleared. Environmental and climate-related damage are expected to worsen and permanently damage natural habitats on the airport development site. A census of waterbirds in Manila Bay revealed that their presence has declined by over 20% since 2017. Massive land reclamation projects – like the airport – are set to see these numbers dwindle even further in the area.

The Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan shared a vision of ‘a sustainable and resilient’ area. It aimed to promote inclusive growth, reduce pollution, restore vital ecosystems and healthy habitats, and mitigate vulnerability to climate-related disasters.

The New Manila International Airport is a far cry from this vision.

Changing landscape: Corporate accountability in the EU

New legislation on corporate accountability – the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive – could make it mandatory for companies operating in the EU to respect human rights and the environment.

It would require companies to undertake human rights and environmental due diligence – an ongoing process that helps companies manage their human rights and environmental risks and prevent harm.

It would apply to companies operating in the EU, and could help safeguard people, the environment and climate from the harmful impacts of corporate activities.

Companies could also be held accountable in European courts for the damage they cause helping affected communities get justice.

However, the current draft proposal still lets companies act with impunity – and doesn’t require that they properly engage with communities or prevent climate-related harms as part of their due diligence duty. If it remains unchanged, it risks allowing damaging business practices, like those reported in Manila Bay, to continue.

Without adequate mandatory and enforceable corporate due diligence to prevent and mitigate human rights and environmental harms, companies can continue to peddle sustainability rhetoric without implementing it.

As EU policymakers finalise and vote on the law, they have a chance to resist corporate lobbies and pass a strong text that puts people and the planet before profit.

Runway Risk

Skirting due diligence

Military intimidation and dodgy company consultations

Monica Anastacio. Basilio Sepe / Global Witness

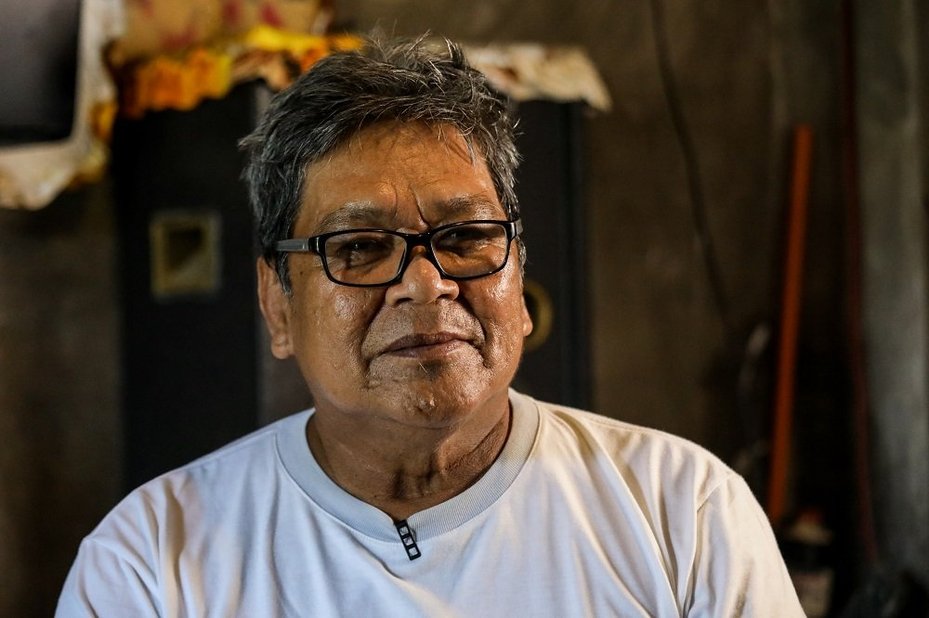

"I often tell the soldiers who question my resolve to defend this land that this is where I was raised, gave birth to all my children, and built my livelihood. I lived there for 52 years."

These are the words of Monica Anastacio, describing her response to intimidation from the Philippine military. Her village is now part of the primary construction site for the New Manila International Airport.

San Miguel’s airport project has steamed ahead despite claims of a coercive consultation process and questionable impact assessments. These assessments have failed to identity and prevent – or in some cases ignored – harms to local communities and the environment.

Homes in two affected villages, or "barangays" – Taliptip and Bambang – have already been demolished. Communities estimate that around 700 families stood to be evicted from Taliptip, and report that fishermen who rely on the bay to make a living have had their livelihoods devastated.

Global WItness

Monica and other Taliptip residents felt intimidated and pressured to leave their homes.

Residents report that representatives of San Miguel visited the neighbourhoods of several affected families to speak about the new airport development. They were reportedly always accompanied by armed soldiers, who were later stationed nearby in January 2020.

When residents asked why the military were present during house calls, soldiers claimed it was to drive out "outsiders" and warned residents not to let them into their homes.

Residents understood this as an attempt to isolate them from public support and scare tactics by authorities to tarnish critical voices – such as civil society groups, scientists, and journalists – as "outsiders" or members of the Filipino communist movements. The military presence on their doorsteps intimidated residents and their families.

Soldiers arrived every day, intimidating our community. They threatened us that if we continue to refuse to leave, something [bad] might happen. That terrified my parents and our fellow [residents]

The residents’ fears of coercion are well founded. Over the past decade, 270 land and environmental defenders have been murdered in the Philippines – the highest number of such killings of any country in Asia.

Of these murders, 47% have been linked to state authorities, with the armed forces implicated in the majority of state linked killings against people that had disputed land rights or environmental harms.

On the island of Luzon, where the new airport is being constructed, 52 defenders have been killed over the past 10 years.

There is a history of allegations against army units accused of protecting companies at the expense of Filipino citizens.

Former President Rodrigo Duterte’s charged and violent rhetoric heightened tensions. It has led to a climate of impunity and an increase in attacks against Indigenous communities, and human rights and environmental defenders.

The practice of "red-tagging" – labelling individuals and groups as communists or terrorists – has become a pernicious practice often used to target activists who frequently end up being harassed or killed.

"It came to a point where they said that the people helping us were [communist rebels] and we should not let them in," recalls Sherly Bacon, a former resident of Taliptip.

A report by the United Nations Commissioner on Human Rights raised concerns over the government’s misuse of new laws like the Anti-Terrorism Act, which allows it to hide behind a rhetoric of public order and national security while diluting human rights safeguards. This has posed a serious threat to civil society and freedom of expression in the Philippines.[1]

San Miguel stated that it has no records of harassment by military or police during community consultation and dialogues, as confirmed by the Local Government Units which requested their presence.

They also say that a Livelihood Restoration Programme, skills training and local hiring priority have been put in place to assist anyone whose livelihood has been affected.

San Miguel conducted two impact assessments for its airport project covering the airport’s land formation and construction. Neither assessment mentions the house-visits with armed chaperones.

Instead, its second impact assessment downplays the military presence in the community, claiming units were stationed in Taliptip at the request of the local council to "secure the project area" and to "prevent outsiders from causing disruption."

The report notes that the military presence was not to intimidate the community, but to "safeguard" against "theft" and "related crimes" given San Miguel’s offer of cash compensation to affected residents.

This diverges from community accounts, which claim that soldiers patrolled the area and pressured residents to agree with the project or lose any offers of compensation.

Armed soldiers stationed in Taliptip in 2020 – in an image captured by a local member of the community. AKAP Ka Manila Bay

Instead, San Miguel’s second impact assessment suggests there was a continuous consultation process about the airport development, beginning with the Silvertides public consultation in February 2019.

"There was a public consultation, but it only happened once in Bulacan," recalls former Taliptip resident Sherly Bacon. "Because many people reacted negatively or showed their defiance during that first instance, they [San Miguel] have conducted house-to-house consultations since. They have avoided talking to the community as a group."

Silvertides’ company presentation – seen by Global Witness – shows there was no mention of a proposed airport development nor the role of developer San Miguel at the February 2019 public meeting.

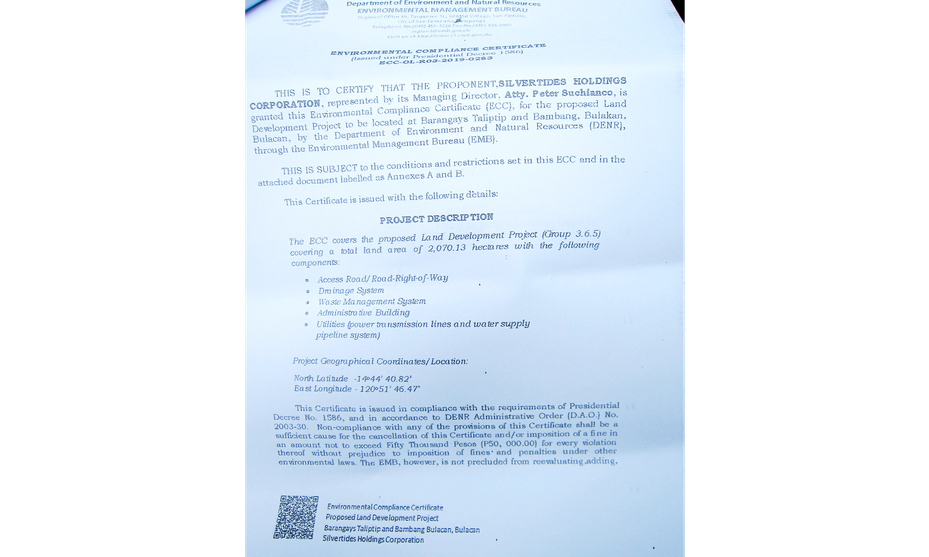

Instead, the community was presented with plans for a land development project covering Taliptip and Bambang to be carried out by Silvertides Holdings Corporation. Silvertides was granted an Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC) for the land development in June 2019.

San Miguel acquired Silvertides in July 2019. Responding to Global Witness, San Miguel states that the ECC issued to Silvertides in June 2019 prior to its acquisition by San Miguel is distinct from the ECC issued to San Miguel in June 2021.

After the takeover, San Miguel’s public engagement activities appear limited, with the company usually opting to speak more often with village leaders – rather than the community at large – to gain public approval for the airport project and arrange compensation.

The company’s first impact assessment makes no mention of prior consultations on the project’s impacts with residents who it would displace. It therefore failed to meet the threshold for meaningful public engagement under Philippines law.

San Miguel held its next public meeting in October 2020, after the airport had received the go-ahead from the Philippine government, essentially presenting the project to local residents as a fait accompli.

San Miguel maintains that the Environmental Impact Assessment it carried out for its ECC application complied with Filipino law governing EIAs (EIA Law of 1978) and that the process designed “appropriate preventive, mitigating and enhancement measures to protect the environment and the community’s welfare” and that the consultations were held with affected communities and other stakeholders.

Global Witness does not suggest that San Miguel proceeded in the consultation process, relocation of residents or in commencing construction of the airport other than in accordance with authorisation from the relevant regional and national-level governmental authorities. The military presence was independent of the developer.

What airport? A lack of transparency and absent safeguards

In September 2019, the Philippine government gave the airport the green-light, allowing San Miguel to start construction at any time. This controversial decision came before the company had produced an impact statement or obtained its own required ECC for the airport project.

According to Philippine law, such certification can only be granted once a company has:

- Assessed its potential environmental impacts, which in turn must reflect local community concerns

- Shown its proposed project will not cause significant negative environmental damage

- Confirmed that it will mitigate identified environmental impacts.

This certification guarantees that a proposed project will not cause significant environmental or social harm and contains specific measures to prevent and mitigate damage during construction, operation and abandonment. This participation should be "open, transparent, gender-sensitive, and community-based", and involve a wide range of stakeholders.

Instead of conducting its own assessment for the airport development, San Miguel appears to have circumvented Philippine law by acquiring Silvertides Holdings in July 2019 and then effectively using the Silvertides' ECC– and corresponding public consultation – that had obtained for a separate "land development" project at the site a month earlier.

Silvertides' ECC did not address the same scope or issues, and its consultation made no mention of either the airport or that San Miguel was involved as the developer.

Silvertides’ ECC outlines a plan for a "land development project" consisting of an access road, waste management and drainage systems, utilities, and an administrative building – with no mention of San Miguel’s new airport

In effect, San Miguel was granted a green-light for its airport before obtaining its own ECC, and presumably relied on the one previously acquired by Silvertides’ as "fig leaf" evidence of due process and meaningful public engagement for the airport construction.

However, copies of Silvertides’ ECC, seen by Global Witness, make no mention of an airport development nor San Miguel [2]. Instead, it outlines a plan for a "land development project" consisting of an access road, waste management and drainage systems, utilities, and an administrative building – it does not specify primary land use activity.

Simple mitigation measures include planting native mangrove species and a workable traffic management programme. These proposed measures are far from adequately lessening the airport’s social and environmental impacts.

Crucially, the document also states that any modification to the approved project would mandate a new environmental impact assessment and another ECC.

Global Witness maintains that because San Miguel had already obtained authorisation from the Philippine government to begin work on an airport in September 2019, after which point it states that it carried out various consultations on its airport project, it was and necessarily would have been impossible to conduct valid consultations or environmental assessments with affected communities, who were unaware of the intended purpose of the project.

In a second impact assessment completed by San Miguel in 2021, the company includes an earlier public consultation for a "land development" in the same area, as part of stakeholder engagement activities undertaken. The presentation, seen by Global Witness, makes no reference to a future airport development expressly.

It appears that the scheme was long in the planning. Between 2011 and 2019, San Miguel – including via one of its subsidiaries – and Silvertides purchased more than 2,233ha of land – the development area of the new airport. They bought another 70ha between 2020 and 2021.

The lack of transparency around its land acquisition for the airport and the consultation process that followed prevented communities from being able to assess the project’s impacts – as well as contest any harms.

San Miguel was eventually granted an ECC for the airport development in June 2021, nearly two years after work was given the green-light. Approval for San Miguel’s airport development appears to be a foregone conclusion, and the eventual granting of the ECC just a token exercise.

Local communities gather outside the Department of Environmental and Natural Resources in Manila in July 2019 to unite in protest and call for the protection of Manila Bay and its fisherfolk. Ted Aljibe / Getty Images

Dutch contracts celebrate "socially responsible" project

Preparations to begin reclaiming submerged land on which the airport will be built started in 2021 and are now in full swing. By the end of 2022, the dredging vessels belonging to Dutch contractor Royal Boskalis had already delivered more than one-third of the material needed to build the huge sand bank. This is the biggest project that Boskalis has ever undertaken.

The development and construction of the New Manila International Airport is insured by the Dutch state via its export credit agency Atradius Dutch State Business (Atradius DSB). Atradius DSB acts on behalf of the Dutch government to support Dutch companies doing business abroad. To cover this project, the Dutch government issued its largest ever insurance policy, valued at €1.5 billion.

In December 2021, Boskalis responded to concerns raised by several Dutch and Filipino NGOs on the project’s negative impacts, indicating it would discuss concerns once San Miguel had completed its second impact assessment. Boskalis later refused to meet with the Filipino NGOs, stating that its invitation was intended for NGOs operating in a Dutch environment.

Outrageously, the CEO of Boskalis later published an op-ed claiming that Both ENDS and Kalikasan PNE, a Filipino environmental organisation, had declined multiple invitations to meet. Boskalis CEO Peter Berdowski has celebrated the project’s "socially responsible manner," emphasising the "eye for the local community and the preservation of biodiversity."

Responding to Global Witness, Boskalis denied that it refused to meet with Filipino NGOs. Instead, it stated that it did not receive responses to its consultation invitation from Dutch NGOs, who had in turn told the company that they would need consult with their Filipino partners about the project.

Boskalis also noted that it when it received the project award in 2020, it was aware that it did not meet international standards, notably IFC Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability and the Equator Principles.

The company states that Boskalis commissioned various environmental and social due diligence impact assessments which resulted in an Environmental and Social Management Plan for San Miguel’s compliance with which is being continuously monitored.

Stakeholder engagement involving a team of community liaison officers is a component of this plan.

The land reclamation process for the New Manila International Airport is Boskalis’ biggest project ever project. Basilio Sepe / Global Witness

Atradius DSB’s Managing Director Bert Bruning insists that the company’s partnership with San Miguel and Boskalis will "ensure that the project will meet international standards in the field of environmental and social conditions," and that it has "made a difference together for local communities and nature."

Atradius DSB claims that before issuing the insurance policy it assessed the airport development’s "possible adverse effects" with "extensive environmental and social screening" – including by making a site visit with the Dutch Ministry of Finance.

During the visit, they met with several undisclosed stakeholders, NGOs and local community representatives, and concluded that San Miguel was "on track" to ensure the project meets international standards.

Responding to Global Witness, Atradius acknowledged "shortcomings" in the initial phase of land development and airport construction. It said that these shortcomings were addressed during Atradius DSB’s primary review of the project and before an insurance policy was issued.

Atradius DSB also told Global Witness that its due diligence process included a review of Boskalis‘ plans to manage the project according to international standards including the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) guidelines.

Export credit agencies like Atradius DSB act as intermediaries between governments and businesses exporting goods or services abroad. They provide financial support, insurance or loan guarantees to reduce the uncertainty of exporting to other countries.

Their role in providing government-backed loans and covering financial risk for companies operating abroad in some of the world’s most volatile markets, makes them critical to national development strategies.

It is essential that they follow OECD guidance on human rights and environmental due diligence.

Local fisherfolk protest against reclamation projects across Manila Bay, including San Miguel’s airport development. Basilio Sepe / Global Witness

In response to this report, Atradius DSB told Global Witness that the project has been thoroughly assessed against international IFC Performance Standards and EHS guidelines.

It acknowledged that the initial proposal for land development and airport construction complied solely with Philippine legislation and not with international standards on mitigation against and compensation for biodiversity and displacement and economic costs, but said that these shortcomings have been addressed.

It says that it has, for example, reviewed how Boskalis will manage the project according to international standards including the OECD guidelines and that it has imposed compliance measures on San Miguel, not least through conditional financing.

Despite citing OECD Guidelines to Global Witness, Atradius DSB has previously stated that it follows less stringent regulations, and believes the OECD guidelines do not apply to it given its legal structure and connection to the Dutch government.

This contradicts the position of the Dutch OECD National Contact Point – an office set up by governments that adhere to the OECD Guidelines – which determined Atradius DSB has a duty to comply with the guidelines.

In the case of the New Manila Bay International Airport, Atradius DSB has failed to ensure that Boskalis implemented the OECD guidelines. It also seems to have failed in fulfilling its duty to assess the project’s environmental and social risks.

The OECD explicitly states that multinational enterprises like Boskalis and Atradius DSB should screen for severe human rights risks and conduct further assessments in cases where risks are identified. This should include, complementing any existing environmental and social due diligence with human rights due diligence.

Although Boskalis claims to apply the OECD Guidelines, its contribution to the social and environmental damage in Manila Bay suggests otherwise. Boskalis’ involvement in this project contradicts its claim to be an industry leader in the field of nature-based solutions that protect and enhance coastal ecosystems – particularly through "biodiversity creation".

"What they took is greater than the return"

What they took from us is greater than what we are asking for in return. Our life before we were uprooted from our former town was abundant and peaceful

After its first impact assessment fell short, San Miguel produced a second one in an effort to reassure financial lenders that the project’s environmental and socio-economic risks had been identified assessed and mitigated.

In fact, its first assessment omits any mention of prior consultation regarding the project’s social and environmental impacts on resident facing displacement. It merely states that communities must be "properly notified", "informed of project developments" and offered an "alternative livelihood assistance programme".

The Dutch state, represented by Atradius DSB, insured the construction project six months after the second impact assessment was completed.

San Miguel offered either relocation or cash as compensation to 359 households or informal settlers it identified as "physically and economically" displaced by the airport development [3].

However, this was only around half of the 700 families that communities say stood to be evicted to make way for the airport. This means the remaining families seemingly received no compensation packages.

Evangeline Ramos, a former resident of Bunutan, a Taliptip neighbourhood, told Global Witness she did not receive any compensation from San Mguel despite living in the area for 20 years.

"There was no meeting and formal announcement of the eviction," says Evangeline.

Instead, San Miguel staff and officers in military uniforms came twice a week and "announced that San Miguel had bought the land, and we should voluntarily demolish our houses to receive compensation."

With nowhere else to go, Evangeline and her husband lived inside a nearby salt barn for six months.

We’re the only family in [the neighbourhood of] Bunutan that were not given financial assistance. I’m calling for San Miguel to equally compensate all those who lost their homes

The minimum amount offered to households who qualified for cash assistance was US$5,227 for wooden homes. Others received more.

"They distributed the compensation during the height of the pandemic and we used it for our daily needs, utilities and rent. They claimed that the money is enough to buy a house and lot, but it’s impossible," says former Taliptip resident Monica Anastacio.

Given the health crisis and military presence, residents told Global Witness that they feared they would not receive anything, prompting some to take the compensation.

The money they gave was not enough. I am here to fight for our right to demand what we deserve. They deprived us of our abundant life, and now we are having a hard time

Many felt that they had no option but to leave. Households who opted for cash settlements have described feeling pressured to accept the money without an alternative on offer.

"Someone came and asked my husband to sign an agreement stating that we will be receiving a lump sum from San Miguel when we voluntarily leave our home. My husband was swayed and […] the documents he signed were immediately forwarded to San Miguel ... There was nothing I could do after [that]," says Monica, who says that she later learned that others were offered a house.

A third of affected residents surveyed in 2019 preferred the offer of a house, according to San Miguel’s second impact assessment. The company says that in the end, this shifted to only six families choosing a house.

However, community members claim that cash compensation quickly became their only option, and that San Miguel stopped offering housing.

"All they could offer was financial compensation because they could not find an area to relocate the residents… people grabbing the cash compensation offered is much more convenient for San Miguel," says Sherly Bacon.

Sherly Bacon’s family continued to demand a new house instead of financial compensation despite feeling intimidated by the military. Only six families from Taliptip received new homes from San Miguel. Basilio Sepe / Global Witness

Sherly and her husband Teody were one of six families who refused to leave Taliptip until granted relocation to a new house: “We stood our ground. If they would not give us the housing we deserve, then we would let ourselves get buried in our community. Because we stood our ground, they gave in to our demands,” says Sherly.

"Those houses were not given to us voluntarily. We fought for it, with sweat and blood," says Teody Bacon.

To receive their compensation, residents had to present valid identification cards and sign a "release, waiver, quitclaim" agreement. The agreement required residents to give up their area for good, to voluntarily demolish their houses, and to undergo screening to qualify for compensation.

The contract also prohibits communities from joining any protests that criticise the company or the project, and prevents them from requesting additional compensation from San Miguel or the local government.

Finally, it commits them to supporting the airport development.

Responding to Global Witness, San Miguel stated that it has put in place a Livelihood Restoration Program (LRP) to address community members’ concerns. The LRP includes initiatives to provide jobs to community members, transitional financial support, remedial work to substandard housing, and a community grievance mechanism.

Destroying a biodiversity hotspot

Dutch "Master Plan" to protect Manila Bay ignored

Residents describe the diverse of wildlife found in Manila Bay. "Do you think these creatures will come back to our waters now? Of course not, because of all the dredging," says Vincente "Bising" Martin. Basilio Sepe / Global Witness

San Miguel’s new airport is causing permanent environmental damage. Formed by 190 kilometres of coastline, Manila Bay’s coastal and marine ecosystems include mangrove forests, expansive mudflats, and seagrasses. The need to prevent development projects from damaging Manila Bay’s delicate marine and coastal ecosystems is recognised by the Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan.

The plan was commissioned by the Philippine government and supported by the Dutch government, which committed expertise and €1 million in funding. It is the latest in a long line of initiatives to preserve the bay from rising economic and climate pressures including a mandate issued by the Philippines’ Supreme Court directing government agencies to clean up, restore and preserve it.

San Miguel’s airport development encroaches upon a recommended ‘strict protection zone’ recognised by the Master Plan, which hosts mangroves, mudflats and key sites of marine biodiversity.

Under Philippine law, these protection zones should be closed to all human activity except for scientific studies, and ceremonial and non-extractive uses by indigenous peoples. However, until the Master Plan is formally ratified by the Philippine government and additional legislation passed legally identifying these specific areas in Manila Bay as "strict protection zones", the site remains vulnerable.

They should stop dredging under the sea, stop destroying marine habitats. If our fish lose their food source and breeding grounds, then they will be gone too

The Master Plan states that the construction of the international airport "will further complicate the already stressed habitat and ecosystem of the area which is continuously hounded by unsustainable economic growth, land subsidence and sea level rise."

It says that given the rate at which the area is sinking into the water, "the risk of flood to people, properties, and investments is quite high" in Taliptip. It concludes that the airport’s construction "will permanently damage the natural habitats" in the area.

It clearly notes that the ideal recourse to avoid damage to local communities, ecosystems and biodiversity is to find an alternate location. Nevertheless, government authorities have approved the project.

Sitio Kinse in Taliptip, before construction of the New Manila International Airport. Oceana

Wetlands of international importance

Manila Bay is subject to several conventions and conservation efforts that aim to protect and conserve its unique biodiversity.

The north of the bay, which includes the airport development site, has been declared an Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) by Birdlife International [4]. Wetlands across the area were also accorded the status of a "Key Biodiversity Area" (KBA) by the Philippine government and Manila Bay is recognised as a key habitat for many migratory birds [5].

Fish and water birds rely on wetland ecosystems as their habitat and food source. They also maintain and improve the water quality and protect local properties from flood damage.

The wetlands at Northern Manila Bay are of immense importance for migratory and resident waterbird populations.

San Miguel's initial surveys to identify bird populations at the project site yielded insufficient information as they were conducted at the wrong time of year according nature conservation experts from The Netherlands. Christian Perez

Building here is a mistake. Manila Bay is a crucial stopping-off point for part of the more than 50 million migratory waterbirds – including 36 globally threatened species – which journey northward from Southeast Asia and Australasia to vital breeding grounds across Russia and Alaska along what is known as the East Asian-Australasian Flyway [6].

"We’re strategically located in the East Asian-Australasian Flyway; the birds migrating during the winter will pass through," says Cristina Cinco, the Head of the Records Committee at the Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP). "They have to find locations where they can feed and rest."

Any alteration in the environment could be detrimental to the bird’s winter food source. She also notes that bird populations have decreased due to developments in other countries, and that the protection of habitats is a responsibility that governments and companies must meet.

In 2018, a technical report by conservation and wetlands experts on habitats and waterbirds in Manila Bay concluded that economic development threatens internationally important water bird sites.

A recent waterbird census in Manila Bay has revealed a decline by more than 20% between 2017 and 2021

San Miguel’s first impact assessment downplays the bay’s ecological significance, concluding that the project area itself is "not a declared sanctuary," despite recognition by the Master Plan that the airport is being built in a recommended strict protection zone.

According to its impact assessment, no threatened wildlife species were found. This includes the assessment of water and migratory bird species within the project area – all of which they claim were of "Least Concern" as categorised by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

San Miguel concluded that "there is a high possibility that the birds will be affected but due to their highly mobile nature they can transfer to other areas."

San Miguel’s second risk assessment, however, identified seven "Key Biodiversity Area" sites that are important for birds and biodiversity located within a 50km range of the airport project.

It also noted that "the [airport] project is considered to be situated in an ecosystem akin to a wetland" and is not located within any legally protected areas.

However, by this point, San Miguel had secured an ECC for its airport project and work on the development had reportedly begun.

I noticed birds perched atop the roof of a large boat because the mangroves and trees where they usually rest are now gone. We are like those birds: lost and have no permanent place to stay … isn’t it sad?

Contributing to climate change

Saving the mangroves

Preserving mangroves and coastal ecosystems is a crucial part of fighting climate change. Basilio Sepe / Global Witness

Mangroves like those found in Manila Bay contain the highest carbon density of all land ecosystems. Scientific studies have shown that mangroves sequester carbon at a rate two to four times greater than mature tropical forests.

If left undisturbed, mangrove forests can act as long-term carbon sinks – removing and storing climate-wrecking carbon from our atmosphere.

Mangroves also filter river water of pollutants and act as natural flood barriers, offering protection from storms and erosion. Their protection and restoration has been proposed as an effective mitigation strategy against climate change.

"The mangroves are our protection against the effects of typhoons and serve as breeding spots and nests for animals. The population of animals has dwindled now that the mangroves are gone." – Monica Anastacio, 2022. Basilio Sepe / Global Witness

But now these valuable trees are being destroyed because of San Miguel’s airport development project.

"We noticed that the sand was depleted since they kept digging," says Sherly. "Then all of the trees were gone because they were cut down. So, nothing shielded us from the waves. That is the most significant change."

Former residents in Taliptip complain about the mangrove destruction – and claim some were cut down as early as 2018.

"Didn't you go and see for yourselves how bare the area is now?" asks Vincente "Bising" Martin. "If you cut a tree, [government officials] would reprimand you right away. But these guys who cleared an entire forest are so free to do so in such a short time."

The airport’s construction will contribute to the destruction of a vast mangrove forest that has almost completely been destroyed since the start of the 20th century.

A local government report from 2018 found that 653 trees were cut down in Taliltip in a "massive cutting". Local government investigators were told that the trees had been cut down on private land in Bulacan allegedly "owned by San Miguel the developer of a proposed airport project."

Silvertides, also described in the report as the alleged developer of the airport, denied any knowledge of the mangrove destruction, and claimed it was not part of the area they had purchased.

Felling mangroves is prohibited under Philippine law. A series of investigations into the destruction proved inconclusive.

Geotagged photos conducted on a spot visit by local government officials in Bulacan show the destruction of mangrove trees in San Miguel’s airport development area in 2018

San Miguel’s first impact assessment points to just two mangrove habitats within the project site. This includes the Bulakan Mangrove Eco-park, reportedly managed by the Philippines government.

Four major mangrove clusters across the airport project area were later identified in the company’s second impact assessment, which also indicates that San Miguel had obtained a permit from the local government to cut trees.

An inventory recorded a total of 4,647 trees – 98% of which were mangrove tree species, over half within the boundaries of the airport project. Almost half of Bulacan’s mangroves will be destroyed because of the airport, according to according to a forest mapping study conducted by the University of the Philippines.

Responding to Global Witness, San Miguel stated that Philippine government permitted the removal and relocation of mangroves, and that the company had engaged consultants to ensure that its offset programme was comprehensive and holistic.

Emissions and environmental impact

The Philippines contributes less than 1% of the world’s global carbon emissions, but it is one of the most vulnerable countries on the planet to the effects of climate change.

An estimated 5 million people are exposed to flooding within Manila Bay – over four times the population of Amsterdam. This will likely rise to 12 million by 2040 given rising sea levels driven by climate change.

The aviation sector is a significant and growing source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. 2020 reports indicate that emissions from commercial aviation were on track to triple by 2050.

The new Manila International Airport is designed to cater for approximately 100 million passengers annually by the project’s end, more than triple the official capacity of the nearby Ninoy Aquino International Airport. When completed, it will be one of the top three busiest airports by passenger traffic globally.

The carbon footprint of the Manila International Airport is set to be huge. According to San Miguel’s 2021 assessment, landing and take-off cycles – the single largest source of potential emissions – will produce an estimated more than 1 million tonnes of CO2 per year. It is estimated the airport’s construction will produce nearly 1.5 million tonnes of CO2.

These emission estimates only cover the first phase of the project, up to the point the airport can cater for 35 million passengers a year. If expanded to its intended capacity of 100 million annual passengers, the airport’s annual emissions will balloon.

Community advocates fear with rising sea levels driven by climate change, the bay – and airport itself – will be underwater by 2050, says Jon Bonafacio, National Coordinator, Kalikasan People’s Network for the Environment. Basilio Sepe / Global Witness

According to analysis in the Master Plan, any efforts to mitigate the negative impact of the airport development, including any restoration efforts of adjacent natural habitats and ecosystems, would need to cover area at least 10 times the footprint of all development activities for the project – on land and offshore.

That would mean that over 25,000ha – 75 times the size of New York’s Central Park – of new mangroves and wetlands.

In any case, many of Manila Bay’s diverse habitats simply cannot be replaced or restored elsewhere. Unless protected, they will disappear – along with all of the benefits they bring to wildlife, local communities, and the climate.

As the airport project moves on apace, the outlook for local communities and the environment is bleak.

"The place where we lived will be completely covered in sea water when you come back after many years," says Vincente. "The land will be gone. That's what is going to happen."

Recommendations

Recommendations for European Union legislators:

1. The EU should provide a robust framework for environmental and climate due diligence in the proposed Corporate Sustainable Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) by:

- Including a comprehensive definition of environmental harm that covers all relevant environmental categories. These categories are already set out in the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and Sustainable Finance Taxonomy.

- Ensuring that companies have mandatory climate due diligence requirements that cover their scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions. These capture emissions that a company produce itself to the ones that result from a company’s indirect activities, such as selling gas, for example.

- Incorporating existing international environmental law standards into the CSDDD, including but not limited to the Paris Agreement, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat and the Aarhus Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making, and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters.

- Providing requirements for effective transition plans in line with the Paris Agreement, including science-based targets for short, medium, and long-term emissions reductions.

2. The EU should ensure adequate stakeholder engagement from companies in the CSDDD by:

- Requiring that companies engage with stakeholders regularly, in a genuine and safe manner that accounts for contextual differences and security risks

- Recognising and codifying the rights and vulnerabilities of human rights and land and environmental defenders, including any risk of reprisals.

- Recognising the rights of Indigenous Peoples, including the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent, as enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- Requiring that companies establish safe, effective, transparent, and accessible grievance mechanisms and conflict mediation procedures aligned with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs). These should provide protections for human rights, land and environmental defenders and whistle-blowers and enable provision of swift remedy.

Recommendations for the Governments of the Netherlands and the Philippines:

1. The Dutch government should:

- Commission an independent and publicly available assessment of the due diligence processes and impact assessments completed on behalf of the Dutch government by export credit agency Atradius Dutch State Business (Atradius DSB) for the New Manila International Airport (NMIA). This assessment should consider whether there are grounds for the withdrawal of the Export Credit Insurance policy.

- Make publicly available all environmental and social impact information about the NMIA project and associated activities. This includes but is not limited to impact assessments, Livelihood Rehabilitation Plans, relevant information from the Environmental and Social Action Plan and Monitoring reports.

- Ensure that Royal Boskalis Westminster N.V and San Miguel Corporation provide immediate and long-term compensation to communities affected directly and indirectly by the project development activities.

- Incorporate stringent social and environmental conditions into future Export Credit Insurance policies and monitor implementation to ensure that companies involved are accountable under these contracts.

- Urgently implement the international due diligence law as currently proposed by the Dutch parliament (IMVO-wet) and advocate at the EU level for a strong Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD).

2. The Philippines government should:

- Commission an independent investigation into the environmental and human rights violations related to the construction of the New Manila International Airport (NMIA). This should include mobilising agencies such as the Philippine Commission on Human Rights and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and closely collaborating with impacted communities.

- Introduce an immediate moratorium on further developments until the environmental and human rights concerns of stakeholders are addressed by San Miguel Corporation.

- Review similar reclamation projects in Manila Bay and other parts of the country.

- Introduce legal and policy reforms to ensure that robust human rights and environmental safeguards are implemented and enforced in similar development projects.

- End state-led "red-tagging" – the practice of labelling individuals and groups as communists or terrorists – against environmental and human rights advocates.

- Honour the state’s commitments under the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership and the Ramsar Convention. This includes promoting and supporting conservation areas that protect globally threatened migratory waterbirds, endangered or threatened species, and habitats within the East Asian-Australasian flyway.

- Ensure the protection of ecosystems, ecological integrity and sustainable development which are included in the Philippines Development Plan (2017 – 2022) mandated by Presidential Order no. 1412-A (2007).

Recommendations for key companies:

1. Atradius Dutch State Business, Royal Boskalis and San Miguel Corporation should:

- Urgently act on the findings of this report, including ensuring that no further harms take place (such as evictions or restrictions on access to land).

- Provide redress and remedy, including but not limited to financial compensation, for communities directly and indirectly impacted by the New Manila International Airport (NMIA) project.

- Put on hold all dredging and project development activities for the NMIA, assess the environmental damage that the project has caused, and restore areas affected by the project development.

- Investigate and report all human rights incidents connected to the NMIA project.

- Make publicly available all environmental and social impact information about the NMIA project and associated activities. This includes but is not limited to all impact assessments, Livelihood Rehabilitation Plans, relevant information from the Environmental and social Action Plan and Monitoring reports.

- Prioritise investment in human rights due diligence to bring business practices into line with international human rights and indigenous rights standards.

- Increase transparency across business operations by publicly reporting complaints and responses to them as well as the results of remediation efforts. Companies should provide timely access to information for affected communities in accessible languages and forms.

Resource Library

Runway Risk

Download ResourceEnd notes

-

The ecological importance of this migration corridor is formally recognised by the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership (EAAFP), a voluntary initiative endorsed by 18 international governments including the Philippines which joined in 2006. Together the signatories have committed to protect migratory waterbirds and their habitats and the livelihoods of communities living alongside them.