Global Witness analysis indicates that some of the targeted refineries have supplied Russia’s military - but the Biden administration prioritises the flow of Russian oil

Russian oil refineries attacked by Ukrainian drones this year have provided Russia’s military with fuel, new Global Witness analysis can reveal, with railway data suggesting several of the plants continued supplying offensive units after the invasion began.

The refinery attacks started in early 2024 and form part of a new front in the war. Ukraine considers Russian oil infrastructure a legitimate military target. But the Biden administration has urged Ukraine to refrain from attacking refineries, arguing the disruption could increase oil prices. Ahead of the US Presidential election in November, Joe Biden is set on ensuring gasoline prices remain affordable across the US - a key factor in candidates’ approval ratings.

The dispute is part of a US strategy which has counterintuitively prioritised the flow of Russian oil onto global markets. Speaking in mid-April, US Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin framed the refinery attacks as a risk to oil markets, saying they could have “a knock-on effect in terms of the global energy situation” and that Ukraine should instead focus on ‘’tactical and operational targets’’.

This new research does not claim to have identified every link between the attacked refineries and the Russian army. Nor does it claim that every refinery attacked by Ukraine has links to the military. But data analysed by Global Witness confirms that a number of these facilities have played a role in fuelling an army that has since laid waste to Ukraine.

Kiev struck two of these facilities, LUKOIL’s Volgograd and Nizhegorodnefteorgsintez (NORSI) factories, in February, March, and May. Reuters reported that the drone attack on NORSI, Russia’s fourth largest refinery serving 11% of the country’s gasoline needs, wiped out at least half of its output. The Volgograd facility, where a fire broke out in May after it was hit for the second time this year, is the largest producer of petroleum products in Russia’s southern border regions with Ukraine.

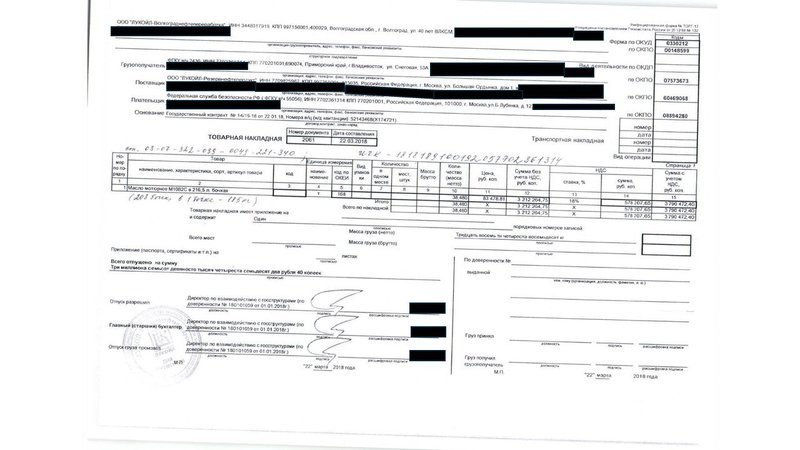

Court documents unearthed by Global Witness show both refineries won contracts with Russian military organisations in the years preceding the war. Arbitration filings show Volgograd and NORSI supplied the Ministry of Defense with oil products back in 2018. NORSI also had a contract to provide jet fuel to Russia’s intelligence agency, the Federal Security Service (FSB), for one of its aviation units in 2020.

Railway data provided by the NGO Anti-Corruption Data Collective (ACDC) indicates those facilities have supplied diesel or jet fuel to the western and southern military districts during the war. These army divisions contain units that have been active in Ukraine since the Kremlin ordered its invasion in February 2022.

LUKOIL Volgograd seems to have sent fuel to the southern military district. It appears to have shipped multiple cargoes for the army division to a town in the west, Gukovo. The Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) was until 2021 tasked with monitoring cross-border movements there in an attempt to reduce tensions following conflict in eastern Ukraine.

The southern military district came to international attention when former Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin claimed to have captured its Russian headquarters as he marched on Moscow in an aborted coup attempt last June. But this belies the actual role it has played in the conflict. The Kremlin, for instance, gave the unit formal responsibility for the annexed regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia in February this year. Human Rights Watch meanwhile claimed the division participated in the siege of Mariupol in 2022, put the estimated civilian death toll of that conflict in the thousands and called for its leaders to be investigated.

In total, Ukraine has attacked at least a dozen refineries inside Russia. Global Witness analysis of railway data suggests several other companies transported fuel to military units from stations that serve targeted refineries. Company websites and a publicly available 2021 Ministry of Defense document show that eight facilities received military approval for their fuels.

Europeans think the refineries are fair game. On April 14th, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe passed a resolution declaring that ‘’under international humanitarian law, Russian oil refineries are to be considered legitimate targets of military attacks’’. Even in the United States, the 2009 Military Commissions Act defines a “military objective” as objects which “effectively contribute to the war-fighting or war-sustaining capability of an opposing force“.

There is a clear precedent for these attacks. But politics, not precedent, is the principle animating the US position. The Biden administration’s stance on refinery attacks looks to be part of a broader goal not to disturb the flow of Russian oil, for fear of disrupting global oil markets. A consensus appears to have emerged amongst Washington, D.C. policymakers that any impairment to Russia’s ability to sell oil will spike prices, thus hurting US consumers and President Biden’s re-election chances.

That logic is flawed. The US does not buy any fuel from Russia directly. Oil prices have been slowly ticking up this year, its true – but as the IEA pointed out in its most recent oil market report, that’s more a result of tensions in the Middle East than fears about the temporary shuttering of 10% of Russia’s refining capacity. By mid-April, Reuters reported that Russia had restored much of the lost capacity. What’s more, Russian oil continues to trade at a discount relative to other grades, primarily because Russia has a smaller pool of available buyers after the embargoes reduced Western demand for Russian oil.

The US has consistently prioritised the flow of Russian oil throughout the war. When the European Union proposed a total ban on the trade of Russian oil back in May 2022, the White House quickly moved to water down the policy. The G7 walked back the complete ban and instead brought in the price cap, which allows Western firms to trade oil below a certain price. It is widely acknowledged to have failed - Russian crude traded well above the cap, with the help of Western services, for much of 2023.

This oil-driven approach is a stark departure from the rhetoric Biden deployed in the days after the invasion when he announced America’s embargo on Russian crude, telling the world America “would not be part of subsidizing Putin’s war”. The dispute over the attacks highlights the distortions of fossil fuel economics, by which the US is desperate to protect the oil exports of an adversary, at the expense of an ally under attack. Unfortunately for Ukraine, oil is taking precedence.

Companies mentioned in this piece did not respond to request for comments from Global Witness.