The EU-backed EastMed gas pipeline depends on a company whose founders participated in a controversial banking scheme that allegedly helped crash Cyprus’s economy

Executive summary

It was cold in Athens – much colder than usual – when leaders of the Anglo-Israeli fossil gas company Energean and Greek pipeline company DEPA signed a deal in January 2020. Flanked by Greece’s Energy Minister, Energean’s CEO promised that the Israeli offshore gas his company plans to extract would be transported into Greece by the EastMed gas pipeline – which DEPA would part-own.

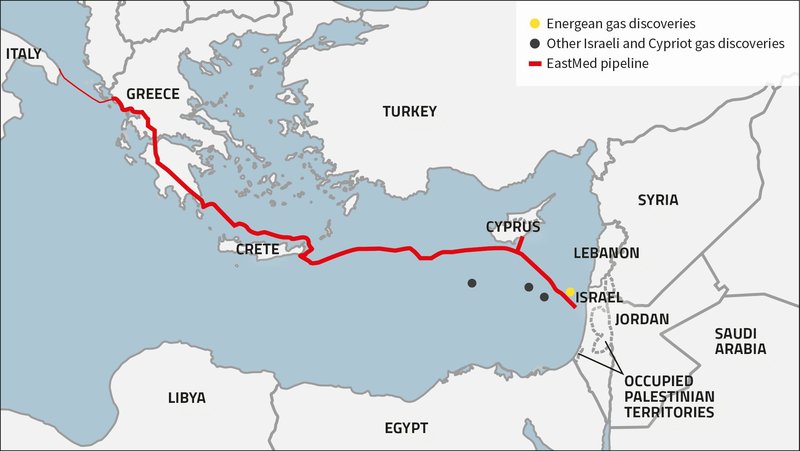

The deal is important for the planned pipeline, which would cost upwards of €7 billion and traverse 1,900 km from Israel’s offshore gas fields to Cyprus and Greece. The governments of Greece, Cyprus, and Israel all support the project. The European Union has also thrown its considerable weight behind the pipeline, granting fast-track status and investing €36 million in EU funds, half of all spending on the project to date. Yet with Energean’s pledge, EastMed had its first – and so far only – source of gas.

This investigation exposes the origins of the London-based company upon which EastMed currently depends for gas and how Energean’s leaders have questionable financial track records. It also shows how EastMed would undermine EU efforts to fight the climate emergency and risks increasing regional military tensions, demonstrating why the pipeline’s financial and political backers should abandon the project.

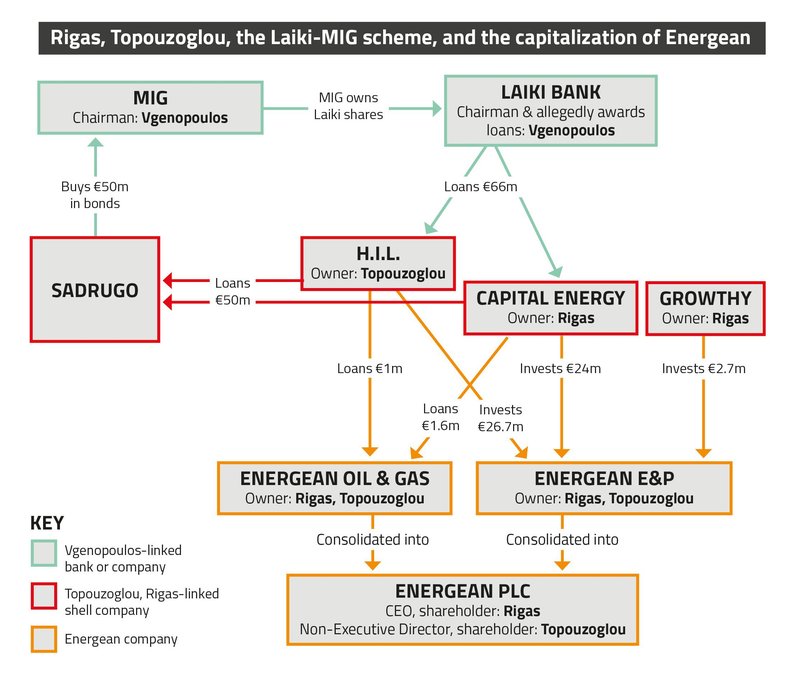

The evidence shows that in 2010 Energean’s co-founders Mathios Rigas and Efstathios Topouzoglou – who today serve as the company’s CEO and Non-Executive Director – took loans from Cyprus’s second largest bank Laiki, and invested much of them in Marfin Investment Group, a faltering business owned by Laiki’s Chairman. The rest they used to capitalize Energean, then in its naecent days.

According to administrators who took control of Laiki after it collapsed, these other and other similar loans used to prop up the Chairman’s business helped break the bank, and with it the Cypriot economy. They specifically pointed to the loans received by Rigas and Topouzoglou as “extremely dangerous;” an example of where Laiki had “unjustifiably grant[ed] loans to third parties” for the benefit of the bank’s Chairman, its managers, and their friends.

Cyprus’s 2013 financial crisis caused thousands of people to lose over €4 billion in savings and led to a €7 billion bailout – again financed largely by EU taxpayers. Yet Energean appears to have emerged stronger, flush with new capital.

Rigas and Topouzoglou state that they are reputable businessmen with long records in the industry, and deny that there was anything wrong with their Cypriot bank loans or that they harmed the country. They and Energean also state that the EastMed pipeline does not depend upon the company because the project is complicated and others will eventually promise to supply it with gas.

Detailed responses from Rigas and Topouzoglou can be found throughout this briefing. For additional evidence used in this investigation, download the report at the end of this page.

In addition to concerns about Energean, EastMed’s financial and political backers should also walk away because the pipeline is likely to further inflame tensions between Greece and Turkey. The two countries are currently locked in a territorial dispute over the waters through which the pipeline would travel.

Lastly, the gas EastMed would transport cannot be used if the EU is to play its promised role in fighting the climate emergency, which of course causes far greater destruction than unseasonable temperatures in Athens. To meet its climate targets, the EU has stated it must reduce gas consumption 90 percent by 2050. Yet operating at full capacity between 2025 and 2050 EastMed’s gas would produce as much carbon as France, Spain, and Italy currently together emit in one year.

EastMed should be abandoned. Global Witness is calling upon the countries involved, the EU, and the US – which announced support for the pipeline in 2019 – to do so. The pipeline is only the latest example of an expensive, climate-wrecking gas project the EU does not need but supports through a law called the Trans-European Networks for Energy (TEN-E) Regulation. Fatally flawed, this regulation is currently under review and should be amended to ensure that the EU stops granting gas infrastructure preferential treatment and taxpayer funds.

Download full report: Hot under the collar

Download ResourceWho wants a €7 billion pipeline?

First proposed to the EU in 2013, the EastMed pipeline is designed to bring large volumes of fossil gas into Europe. The project would start in the Levantine basin, in the waters between Israel and Cyprus, and travel 1,300 km underwater, stopping first in Cyprus and then Greece. After making landfall in Greece, EastMed would continue north for 600 km and connect to additional pipelines carrying gas to Italy and beyond.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, such an ambitious project is expensive. EastMed would be the world’s deepest and longest offshore pipeline, with a price tag of up to €7 billion, not far from the €9.5 billion being spent on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline between Russia and Germany.

EastMed has not been built yet, but is in advanced planning stages. In April 2020, construction companies were offered a chance to submit bids for building the pipeline’s offshore section and a final investment decision about whether to build the project is expected in 2021. If this happens, EastMed would start pumping gas in 2025.

By all accounts, governments from the countries EastMed would connect want the pipeline. In January 2020, the heads of government from Greece, Cyprus, and Israel met in Athens to oversee the signing of a declaration backing the project. EastMed, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis said, would create a “bridge that will drive the region’s natural gas reserves to Europe.”

The US has also thrown its support behind EastMed. In 2019, Congress passed an omnibus budget law for 2020 stating that it is US policy to “strongly support” the development of the pipeline. The same language was not included in the 2021 budget.

However, perhaps the most important backing EastMed has received has been from the EU. Since 2013, the European Commission has granted EastMed Project of Common Interest (PCI) status, requiring member states to give the pipeline preferential treatment and unlocking eligibility for EU subsidies.

This EU support has been critical. Brussels has provided €36 million in taxpayer funds to EastMed – half of all investment in the project to date. Just as important, EastMed’s PCI status has been widely used as a seal of approval by its promoters, including Prime Minister Mitsotakis and the companies that would own or use it.

The companies that would benefit from EastMed

As shown later, if the EU makes good on its pledges to fight the climate emergency, and with it largely eliminate gas use, it is unlikely that Greece, Cyprus, Israel, or the EU would benefit from EastMed. However, the companies that would own the pipeline or transport gas through it have heavily promoted the project, perhaps banking on a failure by the EU to meet its climate targets.

The first of these is IGI Poseidon, which is headquartered in Greece and would own EastMed. It is Poseidon that issued the April 2020 construction tender and has received investments of €70 million to develop the pipeline, including €36 million from the EU.

Poseidon currently has two owners. Half of the company’s shares are owned by the French-Italian energy giant EDF Edison. The other half are held by the Greek pipeline company DEPA International, which in turn is 65 percent owned by the Greek government and 35 percent owned by the publicly listed Hellenic Petroleum.

The companies that may want the gas they produce transported into Europe also stand to benefit. Some of the world’s largest fossil fuel companies have either found, or are looking for, gas off the shores of Israel and Cyprus. These include US companies Chevron and Exxon, Italy’s Eni, France’s Total, and Anglo-Dutch Shell. Lobbying records show that several of these companies have met with US and European officials regarding EastMed, including a concerted push by Exxon to get backing in the US budget.

Above them all: Energean

Few companies, however, have more to gain from EastMed – or are more important to the project – than the Anglo-Israeli gas company Energean. Comparatively new to the sector, Energean was formed in 2007, incorporated first in Greece and then in Cyprus. Just ten years later the company moved its headquarters to London and in 2018 it floated on the London and Tel Aviv stock exchanges. It currently holds exploration and production licenses off the shores of Greece, Montenegro, Egypt, and more recently Croatia, Malta, Italy, and the UK.

The jewel in Energean’s crown is the company’s Israeli operation. The company holds 11 licenses to drill for gas in Israel’s waters that are estimated to contain over 140 billion cubic metres (bcm) of gas – more than Germany and France together use in a year. Energean has not started extracting this gas yet but may begin by the end of 2021, as soon as construction finishes on its new $1.4 billion drillship, capable of extracting 8 bcm per year.

Energean has spent years pushing for EastMed’s construction. The company has deals to sell some of what it extracts to Israel, but also expects to export large volumes elsewhere – between 1.7 and 3 bcm per year.

In its prospectus to investors before going public in 2018, Energean described EastMed as an export opportunity for Israeli gas and has highlighted the pipeline’s EU PCI status. Six months later, the company also met with the top aide to then European Climate and Energy Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete, who publicly supported EastMed. Lobbying records show the meeting focused on “East Med and other projects.”

In January 2020, however, it became clear just how committed Energean is to the pipeline, and how dependent the pipeline is upon the company. At a ceremony held on the same day that the leaders of Greece, Cyprus, and Israel committed to EastMed, Energean signed a deal to transport 2 bcm of gas to Greece through the pipeline.

The deal, which was overseen by Greece’s Energy Minister, was done with one of the companies that would own EastMed – DEPA. According to DEPA’s CEO:

“With the agreement we have signed today – the first agreement for the commercial use of the EastMed pipeline – we are taking a decisive step for the project’s commercial viability and its realization… Thus, a major producer of East Mediterranean gas (Energean) and a key distributor of gas in South East Europe (DEPA) are joining forces to ensure the success of the pipeline."

In April 2021, Global Witness wrote to Energean requesting comment on the relationship between the company and EastMed. In response, Energean stated that it is not the promoter of the pipeline and that the project was also not dependent upon Energean: its DEPA deal was “legally non-binding, non-exclusive letter of Intent as part of good faith negotiations.” The company has no ownership interest in the pipeline and it believed that other companies would also commit to supplying EastMed with gas. It stated that Energean was also not a large player in the region, producing only one percent of the gas needed by countries in which it operates, although these figures did not account for the large volumes of gas Energean would soon produce in Israel.

To date, however, Energean’s EastMed deal is the only commitment by a company to transport gas through the pipeline.

Energean and Cyprus’s financial crisis

Court and business records collected by Global Witness show that the co-founders of the company EastMed depends on – Energean – profited from a controversial Cypriot banking scheme, the likes of which allegedly helped crash the country’s economy. In light of this evidence, those supporting the EastMed pipeline, including the countries and companies involved and policymakers in Brussels, should reassess the project.

In 2013, Cyprus was facing financial ruin as its second largest bank – Laiki – fell apart. In response, the EU and IMF loaned Cyprus €7 billion and the Cypriot government took control of the bank. Yet even with the bailout, thousands of people who banked with Laiki lost savings estimated at over €4 billion and the country’s banks remain saddled today with billions in bad loans.

In significant part, Laiki failed because of the financial crisis in neighbouring Greece. The bank had issued large numbers of Greek loans and bought billions in Greek government bonds, and when the Greek crisis caused the value of these to plummet so did Laiki’s bottom line.

However, there appears to be an additional reason Laiki failed. In 2013, the Central Bank of Cyprus commissioned a review of the country’s banking sector. The review found cases where the country’s biggest banks had “lent funds to an offshore investment company to acquire shares in an affiliate of the [bank] or shares in the [bank] itself.” These loans represented some of the banks’ “largest exposures” and “revealed higher than average losses.”

According to the administrators tasked with running Laiki after Cyprus took over, the bank ran such a scheme: making bad loans to third parties who then invested in companies related to the bank’s Chairman Andreas Vgenopoulos.

In 2010, Vgenopoulos had two jobs. He served as Laiki’s Non-Executive Chairman, but also acted as Chairman of the Marfin Investment Group (MIG), an empire of companies that included Olympic Airlines and the burger chain Goody’s. MIG was not doing well: by the end of 2010 the company had lost €1.8 billion – the largest of any Greek company to date – and its share price had dropped by 60 percent.

According to Laiki’s administrators, Vgenopoulos’s interests in both Laiki and MIG helped lead to the bank’s downfall. In 2012, the administrators estimated that nearly a third of Laiki’s missing money had come from “bad loans,” including “large-scale lending to finance the purchase of MIG shares and other Greek stocks,” Reuters reported. In a lawsuit filed against Laiki’s former managers, the administrators also argued that the bank had issued “unjustified loans,” partly under the direction of Vgenopoulos. These loans were issued to “third parties” so they would buy interests in MIG. The suit is ongoing, with no final judgement yet issued.

The evidence shows that Energean’s co-founders Mathios Rigas and Efstathios Topouzoglou were among those who took Laiki loans and invested them in Vgenopoulos’s business.

Rigas, who currently serves as Energean’s CEO, set up the company in 2007 after purchasing a Greek gas license for £1 million. He holds 11 percent of the Energean’s shares, in part through the Cypriot shell companies Capital Energy and Growthy. His background is in shipping and energy finance as a Vice President with Chase and then as Head of Shipping for the Greek bank Piraeus Prime.

Topouzoglou is a Non-Executive Director and helped Rigas set up Energean in 2007. He owns 10 percent of the company, also partly through the Cypriot shell companies H.I.L. and Oilco. Topouzoglou runs two shipping firms, one of which leases boats to Energean, while the other recently sold the company a $33 million supply boat.

In 2010, two Cypriot shell companies Capital Energy and H.I.L. – which were owned by Rigas and Topouzoglou, respectively – together received €66 million loans from Laiki. The pair then used a third shell company called Sadrugo to purchase €50 million in MIG bonds. In turn, these MIG bonds were used as collateral for the original Laiki loans Rigas and Topouzoglou received.

This does not appear to have been a good investment. The bonds they purchased were apparently unpopular, with investors buying only €250 million of the €400 million worth that were available. Rigas and Topouzoglou held a fifth of the MIG bonds sold. Like other MIG investments, the bonds also lost money, shedding 60 percent of their value by 2013. And Rigas and Topouzoglou should have known better: by 2010 loans from other MIG-linked banks to buy MIG bonds had already been part of a scandal in Greece.

Ultimately, Laiki’s successor bank seized its collateral on the loans and sold the MIG bonds. In 2018, the bank, Rigas, and Topouzoglou reached a settlement in which the pair dropped a claim against the bank for selling the bonds, while the bank agreed to “conclude all outstanding liabilities” owed by the businessmen.

In their April 2021 response to Global Witness, Rigas and Topouzoglou provided extensive professional histories as evidence that they were “highly respected international business professionals.” They stated that they had “no interest in the failure of Laiki” as they also owned shares in the bank, the value of which was ultimately wiped out.

Rigas and Topouzoglou also contended that they had sound reasons for using Laiki loans to buy MIG bonds. They stated that the MIG investment was not bad, as in 2007 the company had raised €5 billion in equity. Purchasing MIG bonds “was entirely legitimate and in accordance with the terms of the loans,” and was “standard and prudent practice” to invest “in a liquid (and hopefully profitable) investment such as the Bond.”

At the same time, the pair questioned the credibility of allegations made by Laiki’s administrators. Some of the evidence upon which the administrators relied was provided by Cypriot lawyer Antonis Glykis who, Rigas and Topouzoglou state, was a partner and five percent shareholder in a law firm convicted of bribery and defended the firm. However, they presented no evidence that Glykis has himself been accused of wrongdoing or how the firm’s conviction was relevant to Energean’s co-founders and the Laiki-MIG loan scheme.

Lastly, Rigas and Topouzoglou stated that, “given the sums involved,” it was “absurd” to state that their Laiki loan helped cause the Cypriot crisis. However, in their suit against Laiki, the bank’s administrators specifically pointed to the loan as “extremely dangerous;” an example of where Laiki had “unjustifiably grant[ed] loans to third parties which eventually benefited MIG and/or [the bank’s managers] and their friends and partners.”

Yet in at least one way Rigas and Topouzoglou do appear to have benefitted from their Laiki loans, as they helped to capitalize Energean. Of the €66 million loaned by Laiki, only €50 million was spent on MIG bonds. According to the pair, the remaining funds were used to pay for Energean gas projects in Greece and Egypt. Indeed, despite the bulk of Laiki’s loans being spent on MIG bonds, Rigas and Topouzoglou claim they were “primarily used” to invest in the gas company.

These funds appear to have helped a young Energean grow. According to publicly-available records, before February 2010 the company – which was then registered in Greece – had a share capital of €16 million (1, 2), although Rigas and Topouzoglou state it had “€24 million in share capital and retained earnings and €47 million in loans and overdraft facilities.”

Depending upon which of these figures is correct, in the year following Laiki’s loan Energean’s share capital at least doubled. In February 2010, Rigas and Topouzoglou established two Energean companies in Cyprus, one of which absorbed the earlier Greek company. These Cypriot Energean entities received investments of over €53 million, from Rigas and Topouzoglou’s shell companies Capital Energy and H.I.L. At the same time, a third shell company Rigas admitted controlling when Energean went public in 2018 provided almost €3 million more. (1, 2)

It is not possible that all of the nearly €56 million Energean received in 2010 came from Laiki’s loan. However, it is clear that the year after Laiki’s loan was a good one for Energean. This is all the more remarkable given the hardship those surrounding the company, including Laiki’s depositors and Cypriot citizens, would soon undergo.

This troubled history suggests that those backing EastMed, including the EU and others, should re-evaluate their support for the project. Such support would benefit a company whose leaders benefited from a banking scheme, the likes of which allegedly helped undermine the Cypriot economy – at great cost to EU taxpayers who bailed out the country. Support is also risky, as more public and private money is provided to a project reliant upon Energean and its founders.

Geopolitical tensions and the climate emergency

In addition to alleged scandals surrounding Energean, EastMed’s backers should also abandon the project because it will exacerbate regional tensions and undermine Europe’s efforts to fight the climate emergency.

As outlined in Global Witness’s 2020 investigation Pyrrhic Victory, EastMed should not be built because it would increase animosity between Greece, Cyprus, and Turkey, which are locked in a dispute over ownership of territorial waters and the gas reserves they may contain. In August 2020, this dispute reached a dangerous high when a Greek warship crashed into a Turkish naval frigate in the contested waters.

EastMed would further inflame these tensions. The pipeline’s planned route passes through disputed sections of the Mediterranean claimed by all three countries and would compete with Turkey’s TANAP pipeline, which brings Azerbaijani gas into Greece and Europe.

Unsurprisingly, Turkey has condemned the project. In response to the January 2020 summit at which both the Greek-Cypriot-Israeli declaration was signed and the Energean-DEPA deal was done, Turkey’s Foreign Minister declared the pipeline “a new example of futile steps” to “exclude” his country.

Just as important, if EastMed is built the gas it would transport would severely undermine the EU’s efforts to combat the climate emergency. By 2050, the EU has estimated it needs to cut gas consumption by 90 percent if global temperatures are to rise no more than 1.5°C – the point at which the worst impacts of climate change may be avoided.

Given that EastMed could transport up to 20 bcm of gas per year, in 2050 the pipeline could produce nearly half of all the gas the EU says it can use. Indeed, if EastMed were to operate at full capacity from 2025 – its planned start date – to 2050, it would produce more carbon than France, Spain, and Italy emit together in a year.

Of course, if the EU does meet its climate targets then EastMed will cease to have a market for its gas and risks becoming a €7 billion stranded asset.

Yet the EU sticks with EastMed

The risks attached to EastMed should be of particular concern to the EU, the support of which has been so critical to the project. The pipeline has enjoyed Project of Common Interest (PCI) fast-track status since 2013, and the EU has contributed half of all investment to date.

This support arises from a European law called the TEN-E Regulation that encourages construction of new fossil gas infrastructure such as pipelines and import terminals. Under TEN-E, proposed infrastructure can obtain PCI status and access a dedicated Connecting Europe Facility subsidy fund. A project can also use its PCI status to seek money from other public sources, like the European Investment Bank, which will continue to finance gas PCI projects even as it phases out lending to fossil fuel projects.

European gas pipeline companies have benefitted considerably from TEN-E. The regulation gifts them, operating through an association called the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSOG), power over which projects receive PCI status.

As a result, ENTSOG member companies like Italy’s SNAM or Romania’s TRANSGAZ have received the lion’s share of taxpayer money spent on gas PCIs. They have also benefitted from the €440 million in gas subsidies that have been wasted on projects that have failed or are likely to – all of which have been backed by ENTSOG members.

Fortunately, TEN-E is currently being reviewed to bring it in line with the European Green Deal. However, the current proposed changes – published by the European Commission in December 2020 – would still allow for fossil gas infrastructure to be supported by the EU and do little to remove ENTSOG’s power. It is now for the European Parliament and Council, which are currently reviewing the Commission’s proposal, to do the right thing and end EU support for gas.

Time for change

At present, those backing EastMed do not appear to have doubts about the project. One year after Energean committed to using the pipeline and the leaders of Greece, Cyprus, and Israel pledged support, EU officials again signalled they were on board. In January 2021, the Commission included EastMed in its fifth list of proposed Projects of Common Interest.

That same month, Energean announced it had borrowed $700 million, most of which will be spent on its next Israeli gas project, near where the EastMed pipeline would begin. This was followed in March by €100 million in loans and loan guarantees awarded to the company by the Greek government and a successful $2.5 billion bond issuance. At the same time, however, the urgency of the climate emergency has only grown, as EU scientists announced that 2020 had been Europe’s hottest year on record and that greenhouse gas emissions had rebounded after falling during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

And in Istanbul, while “exploratory” talks between Greece and Turkey began, they came amongst signs that tensions between the two were still high. On the same day, Greece’s Defence Minister had finalized a deal to buy €2.5 billion worth of French fighter jets.

This continued support for EastMed, by the countries along the pipeline’s route, by the companies that would own or transport gas through it, and by the EU, is a mistake. EastMed is a threat to efforts to fight the climate emergency and to peace in the region. As this investigation has shown, it is also a risky bet because the co-founders of the company upon which it currently depends – Energean – having a questionable financial past. In particular, Cyprus and the EU should reject EastMed because these leaders benefitted from a banking scheme the likes of which allegedly helped crash the Cypriot economy, hurting thousands of Cypriots and costing EU taxpayers billions.

But cancelling EastMed is not enough. It is only the latest in a list of EU-backed projects that have descended into scandal, and it is only one of 41 gas projects that the EU may support on its latest proposed PCI list. This list, which will be finalized by the Commission at the end of 2021 and voted on by the European Parliament in the following months, should be amended to remove all gas projects. The European Parliament and Council should also amend the TEN-E Regulation that encourages support for gas projects like EastMed in the first place.

Recommendations

The European Commission

The Commission should remove all gas projects, including EastMed, from the current proposed fifth list of Projects of Common Interest (PCI).

The European Parliament and Council

The TEN-E Regulation, currently under review by the Parliament and Council, should be changed to end:

- The EU’s support for projects that transport, store, or depend upon fossil gas.

- The power of ENTSOG to influence EU gas policy, including which Projects of Common Interest are chosen, replaced by a governance system that is genuinely independent and fit for driving the energy transition.

If presented with the fifth PCI list that includes gas projects, including EastMed, the Parliament should vote against these projects.

The governments of Greece, Cyprus, and Israel

All three governments should withdraw support for the EastMed pipeline and ensure it is cancelled.

Cyprus should ensure all of those who may have broken laws related to the collapse of Laiki Bank are investigated and, where appropriate, brought to justice.

The United States government

The US should end all backing for the EastMed pipeline, including ensuring that support provided for in the 2020 Appropriations Act is not repeated.

Download full report: Hot under the collar

Download Resource