Key findings

The climate crisis is no longer projection, but reality. Forests play a key role in regulating the global climate and are critical to preventing runaway global heating. They are also a treasure trove of biological diversity, and home to many Indigenous peoples and forest communities. Yet forests continue to be burned and destroyed at an alarming rate. The primary driver of deforestation is agribusiness, with palm oil a chief culprit.

Global Witness went undercover to investigate the growing threat facing Papua New Guinea’s (PNG) communities and tropical forests from palm oil companies driving widespread deforestation and human rights abuses.

This investigation now implicates three of PNG’s newest palm oil producers in what appears to be serious criminality and other harms.

For the first time, we show how this tainted product is being sourced by world-famous brands and their business financed by iconic banks and investors:

- Palm oil executives and senior employees tell undercover Global Witness investigators they bribed officials including a Papua New Guinean government minister, paid police to brutalise villagers, used child labour, and participated in an apparent tax evasion scheme.

- The Malaysian-backed firms clear-felled tens of thousands of hectares of Papua New Guinean rainforest, which supports rural communities and is among the most biodiverse in the world.

- Tainted palm oil and its derivatives from Papua New Guinea plantations were sold on to well-known big brands including Kellogg’s, Nestlé, Colgate, Danone, Hershey, and PZ Cussons and Reckitt Benckiser, the parent companies of Imperial Leather and Strepsils.

- One palm oil firm, Rimbunan Hijau, negligently ignored repeated and avoidable worker deaths and injuries on palm oil plantations.

- Global financiers such as BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, are indirectly profiting from these human rights and environmental abuses through investing in banks notorious for financing harmful palm oil firms.

A pattern of coercion and violence right across PNG has denied local people the traditional use of forests integral to their culture and livelihoods.

Huge areas of tropical forests have been deforested, and much more remains at risk unless action is taken.

Global Witness is calling for companies named in this report to be held to account for causing, contributing to or profiting from harms linked to their global operations.

International financiers ought not to be bankrolling these companies – and governments need to regulate to stop bankers enabling this industry’s excesses.

The true price of palm oil

Introduction: An industry unchecked

When the boys woke up, they were at gunpoint. They tied their hands at the back and blindfolded their faces so they could not see

It is late at night in July 2019, and a pair of off-road vehicles wind their way through the rainforests of New Britain, a crescent-shaped island off the north-east coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG).

The transport has been paid for by a palm oil company.

Onboard are police armed with guns and metal bars who have received an "allowance" from the company. In effect, this is a private army.

On arrival at the village of Watwat – where nearby oil palm trees have been vandalised by persons unknown – the armed officers dismount, intent on retribution.

They then launch a violent raid on the village.

Men and boys as young as 16 are dragged from their beds, beaten with metal bars, and thrust down into the mud at gunpoint, lying prone as tropical rain lashes from the sky.

They will be blindfolded and arrested, then held for weeks, only to be released on payment of bail that the villagers can scarcely afford.

Welcome to Papua New Guinea’s palm oil industry, where such brutality is commonplace.

Global Witness now tells the story of communities across the country harmed, terrorised, and impoverished in pursuit of a liquid gold foodstuff that has found its way into the supply chain of global brands including Kellogg’s, Nestlé, Danone and Hershey.

And a Global Witness undercover investigation helps unpick a web of apparent tax evasion and corruption, tracing money flows from financiers in the US, UK and EU to this troubled new frontier of the global palm oil industry.

A growing threat

Chances are you have consumed some palm oil already today. Despite growing awareness of its association with deforestation, it is the most common vegetable oil in the world, appearing in everything from baked goods to instant noodles to shampoo and baby formula.

And in PNG, palm oil is an industry poised to explode. By 2030, the PNG government aims to have 1.5 million hectares (ha) under oil palm cultivation, compared to about 150,000 ha in 2016 – a ten-fold increase.

Yet, there is no national policy guiding this expansion and creating safeguards to ensure communities are protected from acquisitive corporations.

Papua New Guinea’s history of land and forests mismanagement makes this an urgent issue.

A South Pacific nation, PNG makes up half of the massive island of New Guinea, home to the world’s third-largest remaining rainforest.

The country’s borders include hundreds of smaller islands, and it controls an area of ocean over 10 times the size of the UK.

It is home to at least 5% of all species on Earth, many found nowhere else: forest dragons, tree kangaroos, resplendent birds of paradise and the only known night-blooming orchid. Billions of metric tons of carbon are stored in the country’s towering trees.

With a population likely above 8 million, richly diverse cultures have developed in PNG, with more than 800 languages spoken.

Most of PNG’s people live in rural areas and rely on their land, seas, and forests for at least some of their livelihoods. In turn, communities have carefully managed the biodiversity of their local environment for generations.

Papua New Guinea has strong laws to protect Indigenous peoples’ rights and its stunning biodiversity, but these are rarely enforced. Civil society and even the PNG government itself have documented its egregious failure to uphold these laws.

This failure is on stark display in the sectors now dominated by Malaysian-owned logging and agribusiness companies.

New kids on the block

At the turn of the millennium, Malaysia itself was losing its forests faster than any other nation on earth. In just 12 years, it lost 14% of its rainforest, much of which was cleared to plant oil palm.

Before long, its logging companies sought new opportunities abroad. They did not have to look far.

In PNG, they came to dominate the logging industry, making it the world’s largest exporter of tropical timber by 2014. Some of these companies then planted oil palm on land they had cleared.

Global Witness has spent two years investigating three such companies that began exporting palm oil from PNG since 2014: the East New Britain Resources Group (“ENB”), the Rimbunan Hijau Group (“RH”), and Bewani Oil Palm Plantations Ltd (“Bewani”).

Together, these companies have recently cleared tens of thousands of hectares of climate-critical rainforest in PNG.

Despite the growing urgency of the climate crisis, global financiers have propped up these companies’ deforestation in the expectation of profit.

Their palm oil has now reached major consumer markets, via favourite brands like Hershey and Kellogg’s.

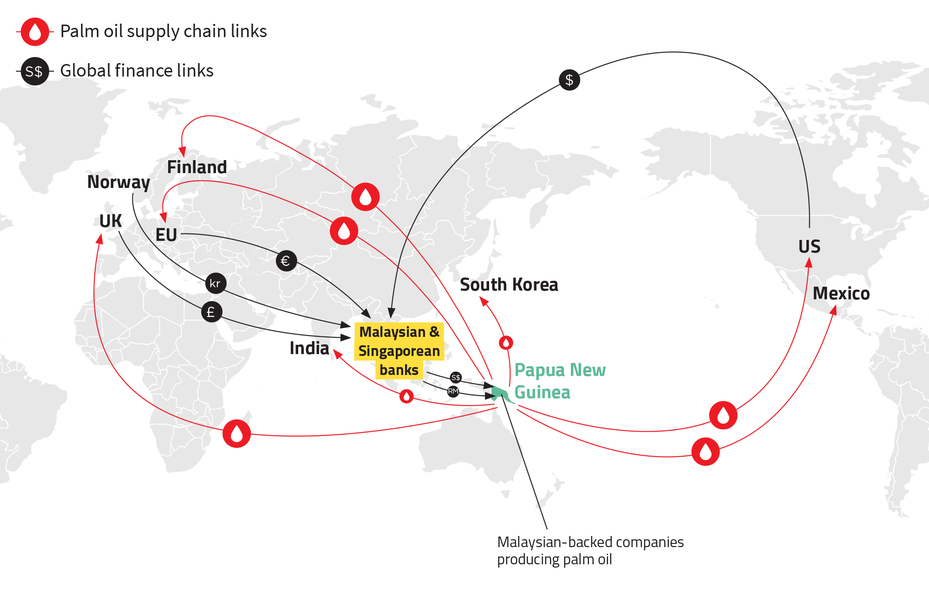

The production of palm oil in PNG is enabled by global finance. Palm oil from these plantations has been sold around the world. This illustration depicts some of the flows of money and palm oil examined in this report

East New Britain Province is home to thousands of square kilometres of rainforest, and to operations of two of the oil palm producers that are the subject of this report.

In October 2019, a team of Global Witness reporters drove south through the province to Watwat, site of the police’s night-time attack on village boys.

An elderly villager, Sharon, whose name has been changed to protect her safety, described how someone had vandalised palm trees there – destroying more than a thousand – and the Royal PNG Constabulary sought culprits.

According to Sharon, they singled out five Watwat youths.

“The police were beating them and asking them who cut the oil palm tree,” she recalled to Global Witness reporters.

Police dragged the young men and boys out of bed, blindfolded them and tied their hands behind their backs, she said.

Reporters were told officers beat the young people with metal bars and the flats of machetes, “jumping up and down on [a victim’s] back."

The men and boys were then taken to Kokopo, where police allegedly hit their heads against posts to elicit confessions before they were charged with criminal damage.

Global Witness has been unable to determine whether these charges led to convictions.

Sharon told Global Witness the car that police arrived in was owned by a company called Tobar Investment (“Tobar”).

“The company has a lot of money,” she said. “They are able to give it to the police. The police were working for Tzen Niugini [an ENB company closely linked to Tobar].”

Global Witness asked the residents of Watwat whether anything good had come to their community from palm oil development.

“Only destruction,” Sharon said.

To investigate these allegations, Global Witness went undercover.

Drawing on fieldwork and satellite imagery and by following the money, Global Witness exposes in this report the growing threat facing PNG’s communities and forests from palm oil companies that have acted unaccountably, yet are financed by the world’s biggest banks and sold to global brands.

Global Witness focused on three Malaysian-backed palm oil producers: the East New Britain Resources Group, the Rimbunan Hijau Group and Bewani Oil Palm Plantations Ltd.

Our investigation widened to include a PNG-owned company, Tobar Investment Ltd, as serious admissions of corruption and police violence were made to our reporters.

This report exposes instances of apparent tax avoidance, corruption and abuses of both local communities and their environment.

We then reveal the financial actors profiting from these acts, as well as the global brands sourcing the companies’ product.

The investigation concludes by recommending the changes urgently needed to safeguard PNG’s communities and environment and hold these corporations accountable.

Tobar's laughing villain

Tobar Investment Ltd is a Papua New Guinean-owned agribusiness company with palm oil plantations around Watwat.

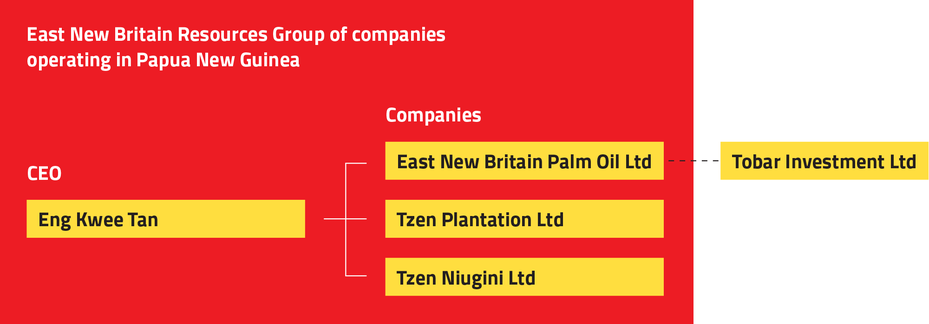

It operates under a joint venture agreement with East New Britain Palm Oil Ltd (ENBPOL), part of the ENB Resources Group of companies.

This group is one of two major palm oil producers, along with Rimbunan Hijau, that have deforested thousands of hectares in East New Britain Province since 2010.

Tobar Investment Ltd is a Papua New Guinean-owned agribusiness company with palm oil plantations around Watwat. It operates under a joint venture agreement with East New Britain Palm Oil Ltd (ENBPOL), part of the ENB Resources Group of companies

One of Tobar’s founding directors is Edward Lamur, a jolly figure and the former deputy provincial administrator for East New Britain.

In February 2021, a Global Witness investigator posed as a commodities trader facing resistance from communities at a fictional plantation in Thailand to ask how the police helped Tobar with the Watwat development.

“We had some problems when we were planting, before we … when we were preparing the land to plant, some people wanted to disturb us,” Mr Lamur said. “So we got police ... we sat down with them ...”

Mr Lamur chuckled and said, “They did some bashing up ...”

“Beating them?” the investigator asked.

“That’s correct,” replied the businessman. “… Even at night those culprits … who you know did trouble and ran away to the hiding places … so we went after them in the night, got them, belted them up and locked them up at the station.

“… I made sure those operations were done,” he added. “They know we are owners now.”

Later confronted with his own admissions, Mr Lamur did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Global Witness.

Mr Lamur described the influence of both Tobar and ENB over the police.

Both companies “assisted with logistically paying for police, you know … fuel, cars,” he said.

“... When they [villagers] are aggressive, we naturally use a little bit of force on them … So the story you know went around, oh police … you know these people are doing this and this.

"And police … So … we quietened things down. No more, no more unnecessary disturbance to our workers who were planting.”

On a later phone call, Mr Lamur doubled down on his claims of this cosy relationship with the constabulary.

On questioning, he confirmed that a former member of Tobar’s staff had worked simultaneously as a police reservist. Then the businessman went further yet.

“There is a special operation police,” he said. “The boss is actually a very close friend, we work hand in hand with them … whenever we want assistance…”

Global Witness said: “So, whenever there is a problem, you can call this special operation police and they help you?”

“... Yeah, we’ve got the boss’s mobile number,” Lamur said. “We just call or text any time.”

Mr Lamur, the former deputy provincial administrator, has higher political aspirations. In 2017, he stood for the Kokopo Open seat in PNG’s Parliament. Will he run again?

The Royal PNG Constabulary did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Global Witness.

ENB said: “We generally deny all the allegations.”

A spokesperson called Global Witness’s findings “baseless and untrue”.

They added: “Both Tobar and ENBRG deny any use of the Royal PNG Constabulary to cause any violence against any person or detain anyone illegally.”

Global Witness did not receive a separate reply from Tobar.

Political connections

Oil palm attracts powerful men. Another founding director of Tobar is Leo Dion, the ex-governor of East New Britain Province and a former Deputy Prime Minister of PNG.

(Mr Dion is still listed as a director in company filings but, according to Mr Lamur, he is no longer in that position.)

Asked whether having a Deputy Prime Minister on the board of Tobar was useful, Mr Lamur told our undercover reporter: “Yes, he was very good for us and very good for Mr Tan [ENB’s CEO Eng Kwee Tan] and them too.”

“So he could secure some special deals, I guess, with the ministry, or not?” asked Global Witness.

“That’s correct, that’s correct,” replied the businessman.

Contacted by Global Witness, Mr Dion said he “offered help in acquiring coconut plantations during the early years of the former chairman of Tobar Investment Ltd Joseph Lupin when I was the governor then helping our grassroot people [sic throughout] to take ownership of foreign own plantations here i[n] ENBP.”

He added, “Any other Tobar Investment businesses carried out after the death of Mr Joseph Lupin has nothing to do with me.

“I denied any participation in any way by words or actions to condone anything that is illegal and unlawful.”

Global Witness has found no evidence that improper deals did actually take place under Mr Dion’s auspices.

But as we shall hear, Mr Lamur’s partners at ENB are no strangers to "special deals" themselves.

Global Witness’s undercover operatives infiltrated the higher echelons of ENB itself, dining on separate occasions with both senior managers and with the chief executive.

This yielded admissions of serious white-collar crime and human rights abuses – which allegedly go right to the upper echelons of Papua New Guinean politics.

East New Britain Resources Group

Total forest destroyed, 2007-2019: 18,900 ha

Deforestation in plain sight – forest clearance surrounds ENB’s Liguria mill in this mosaic of satellite imagery from 2017-2018. Global Witness

In a palm-thatched Kokopo restaurant that overlooks a smoking volcano across the harbour, two senior ENB executives readily admitted that bribery to obtain logging permits and access to land is a regular cost of doing business.

Tzen Niugini’s Land Acquisitions Officer Bernard Lolot and public relations kingpin Michael Paisparea were in a boastful mood when they met Global Witness undercover reporters for a business dinner in October 2019.

Asked whether a “special favour” had convinced government officials to approve projects, Mr Lolot said: “Of course … that’s what a lot of the leaders, they want. … Some school fees and they ask for token and all this.”

“What is a token? A nice Land Cruiser?” asked Global Witness.

“Yep, things like that,” Mr Lolot replied.

“... Sometimes they’re bringing all this stuff back to their own areas.”

"Unofficial fees"

Mr Paisparea went further, acknowledging gifts to secure the renewal of a logging permit.

“… Giving something to the minister, to the secretary, to [National Forest] Board members …” he said.

Asked whether this constituted "unofficial fees", he replied: “Yeah, that’s right ...”

He said: “Roughly, sometimes the minister need about a hundred thousand, fifty thousand [Papua New Guinean kina].”

Fifty thousand kina was about £10,000 at the time of writing.

Asked if the chairman of the National Forest Board also needed paying, Mr Paisparea said: “Chairman as well.”

Our reporter probed: “So [in total for one permit], you pay half a million?”

Mr Paisparea responded: “That’s right. It’s enough.”

In addition to his work for ENB, Mr Paisparea serves on the East New Britain Provincial Forestry Management Committee (PFMC), which assesses new forestry projects and recommends to the national board to approve or reject them.

This presents a serious conflict of interest. Although Mr Paisparea said he does not rule on his own projects, the position may nonetheless allow him influence over other members.

Asked about official fees, Mr Lolot said: “The official fee’s not so much … 200,000, 150 [thousand PGK, about £30,000].”

Explaining how to convince individuals to sign papers suggesting the company has rights over their land, Mr Paisparea said: “Request of the school fee, I come there and we help them.”

“... Because these things are not in [the official] the agreement.”

Global Witness has been unable to discover what projects these claims may refer to. Nor can we rule out that they were groundless boasts.

However, the comments suggest a detailed understanding of who needs to be bribed, such as the knowledge that the secretary and board members would need to be bribed in addition to a minister.

Global Witness is not suggesting that any employee, minister or member of the Board did in fact accept a bribe.

The PNG Forest Authority did not respond to repeated requests for comment, including a letter hand-delivered to its headquarters.

In its response, ENB denied bribery and corruption, writing, “We generally deny all the allegations” put to it by Global Witness.

It added: “Most of your allegations are all hearsay with no accurate details."

In an apparent reference to Mr Paisparea’s position on the PFMC, it said: “Renewal of existing and new forest projects are only approved by the PNG Forest Authority.”

While this is true, the PFMC provides recommendations to the Forest Authority.

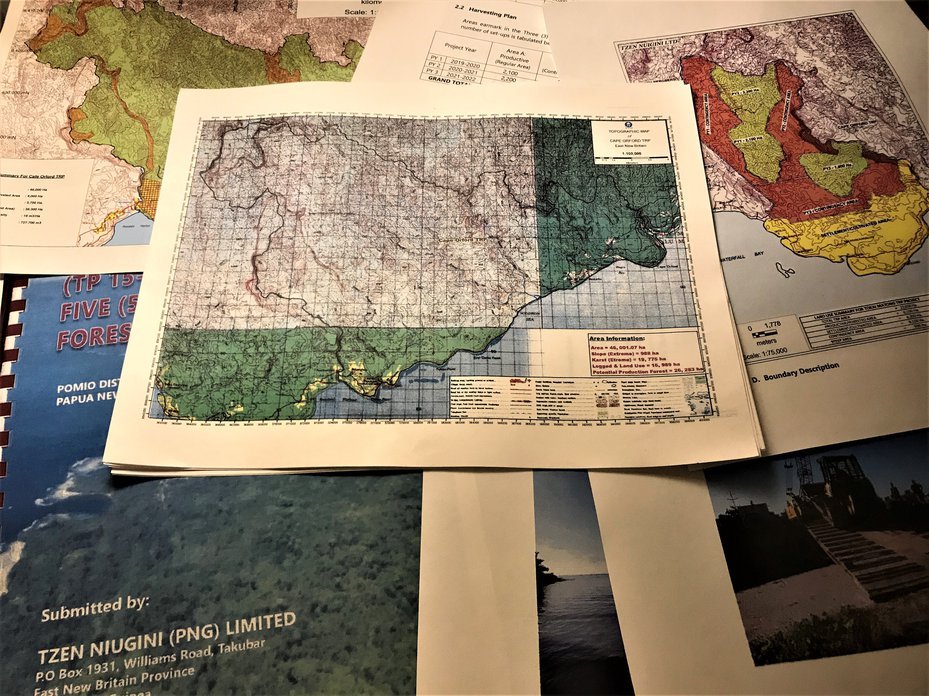

Following the dinner, Mr Lolot supplied Global Witness with numerous maps and documents relating to several logging and agriculture projects, showing his intimate involvement with major deforestation plans.

An employee of the East New Britain Resources Group shared documents from numerous logging projects with an undercover Global Witness reporter. Global Witness

Eight months later, in a follow-up telephone discussion, an undercover Global Witness reporter repeated Mr Paisparea’s bribery admissions back to him.

He did not deny them, and conceded paying “allowances” to entice individual customary landowners whose forests Tzen Niugini coveted, although he said they did not offer Land Cruisers in that instance, which is why a rival company obtained access to the land.

Communities’ traditional use of their land is protected by the country’s laws and constitution, making virtually every Papua New Guinean a landowner.

Most of the country is still under the legal control of such customary landowners, at least on paper.

But these laws are poorly enforced, allowing companies like ENB to exploit rural communities and setting people against their neighbours.

Papua New Guinea scores dismally on Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index, scoring a mere 27 points out of 100 in 2020.

This puts it in 142nd place out of the 180 countries assessed.

Child labour

During the Kokopo dinner, Mr Lolot and Mr Paisparea also admitted the company used child labour, with schoolchildren as young as 10 working on their plantations.

Mr Lolot conceded this was against PNG law. He had added just before: “Sometimes we bend the rules just to make things happen.”

Employing a person under 16 years of age in work that is likely to be injurious is an offence under the PNG Employment Act.

PNG is also a signatory to the Convention on the Worst Forms of Child Labour, which defines this category to include work in an environment likely to harm the health or safety of children.

Children working on a palm oil plantation therefore constitutes an offence under both the PNG Employment Act and Convention.

ENB said Global Witness’s allegation that it used child labour was “absurd and denied”, and it upheld PNG child labour laws.

(Following publication of this report, Global Witness sighted letters from the superannuation fund Nasfund and the Papua New Guinea Department of Labour and Industrial Relations indicating that ENB does not employ children under 18.)

Oil palm plantation workers carry out heavy labour. They are at risk of musculoskeletal injuries, infectious disorders including malaria, pesticide exposure, and sexual harassment and rape.

As Global Witness’s investigation reveals, deaths among workers are commonplace.

Women threatened at gunpoint

A mediation process in East New Britain Province in June 2018, which brought to light serious allegations by villagers against the ENB group, also implicated Mr Lolot and Mr Paisparea.

Multiple witnesses said the ENB company Tzen Niugini “brought in” police officers to Pulpul in the East Pomio region to coerce community members, as landowners, into signing agreements for a logging project.

In an incident with strong echoes of the Watwat village repression, police allegedly forced the men into a shed at gunpoint and held them there for hours and threatened the women at gunpoint.

Pulpul community members alleged police punched the village magistrate and beat him with a fan belt.

The aim of this atrocity, according to members of the community, was to override objections they had already voiced to Mr Paisparea and Mr Lolot, when they had rejected the idea of this new development.

Speaking to a local NGO, villagers claimed that this physical abuse had happened on Mr Lolot’s land.

Mr Paisparea and Mr Lolot did not respond to Global Witness’s subsequent requests for comment.

ENB said: “ENBRG has complied with all Forestry and Environmental laws in Papua New Guinea and denies participating in any illegal activity in connection to any Forest projects or planting of oil palms.

“ENBRG has and continues to comply with all land laws in Papua New Guinea to acquire and/or develop land.”

During their dinner with Global Witness, Mr Lolot and Mr Paisparea revealed ENB was running two palm oil projects: one in Pomio District and the other in Gazelle District at the north end of the province.

As we shall see, at the latter site the company stands accused of brutally evicting smallholders and bulldozing their homes and cacao trees.

But the pair were not the only ones who made damaging admissions.

Their Malaysian boss Eng Kwee Tan, chief executive of the ENB Group, also confessed to a tax evasion scheme on an international scale.

Kokopo, the capital of East New Britain Province. Global Witness

Admissions of tax evasion

“I would also be lying to you if [I said] there is no conflict,” Mr Tan told a Global Witness undercover reporter over a dinner of red snapper. “We do have conflicts, but solvable conflicts.

“We have people, you know, that come and stop our work … and I think this is a common phenomenon.”

Mr Tan was referring to local villagers. Land conflicts are a frequent by-product of palm oil plantations.

In a swanky hotel in the port town of Kokopo, the businessman bragged of owning no fewer than 20 German Shepherd dogs – and soon it became clear how he can fund such indulgences.

Halfway through the meal in October 2019, he made the unprompted remark that palm oil destined for India “has to come from Malaysia, otherwise they impose taxes.”

“So we have to make it show like it come from Malaysia,” he continued. “It’s always a bit technical.”

The reporter replied: “Oh, so it goes on the paper to Malaysia. But directly to India.”

Mr Tan said: “Yes, yes. So we make it that it comes from Malaysia.”

He continued: “The vessel has to go to Malaysia, offload the PKO [palm kernel oil], and then offload the CPO [crude palm oil] in India.”

This would appear to be an admission that the ENB Group has dishonestly evaded the imposition of import duty on its palm oil exports to India.

Such a scheme could have benefitted the company by claiming preferential Indian tariffs for palm oil exports from Malaysia rather than from PNG.

Watch the tax gap

Between March 2018 and 27 November 2020, India taxed crude palm oil imports from countries it did not have free trade agreements with – including PNG – at a base rate of 44%. But Malaysian imports were not taxed as heavily.

In 2019, when Mr Tan spoke to an undercover Global Witness researcher, the Malaysia-India Comprehensive Economic Cooperative Agreement (MICECA) established a duty on Malaysian palm oil of only 40%.

India also charges a Social Welfare Surcharge equal to 10% of the total duty on imports, in addition to the import duty itself.

In 2019, this resulted in a 4.4 percentage point difference between tariffs levied on PNG and Malaysian imports of palm oil to India.

This tax gap appears to lie behind Mr Tan’s scheme.

And our research shows shipments were indeed made by ENB to India in the relevant period.

Tracking the tankers

This quantity matches Mr Tan’s estimates to our undercover reporter of his total monthly exports.

A documented journey therefore supports Mr Tan’s assertion that ENB exports palm oil from PNG to India.

Yet the Kolkata Port document describing the Chem Peace’s palm oil delivery indicates only that the vessel had been in Pasir Gudang, Malaysia.

It does not state that the palm oil originated from PNG.

This would appear to be a smoking gun that in 2019 at least one ENB palm oil delivery to India was not accurately badged as coming from PNG.

No paper trail

There is further supporting evidence of this. In 2018, commercial shipping records show, an “ENB Trading Ltd” exported one shipment of palm oil from PNG to India.

(An entity registered in Singapore, “ENB Trading & Shipping Pte Ltd”, appears to be wholly owned by the British Virgin Islands-registered company that also owns East New Britain Palm Oil Limited.)

Yet for 2019, not a single shipment appears in these records as being exported from PNG to India by ENB Trading. This is despite the voyage plotted above.

Mr Tan told our undercover reporter that ENB exports approximately 5,000-6,000mt of crude palm oil per month.

In 2019, palm oil prices averaged 2,248 Malaysian ringgit per ton (about £414, at December 2019 exchange rates).

Global Witness calculates that if each of the two 2019 shipments we tracked carried an average of 6,000mt, they would have been worth about £4,970,400.

That year, the 4.4 percentage point tax gap meant that if the full cargo was unloaded in India, the Indian government would have lost out on about £219,000 of public revenues compared to if it had been honestly labelled.

East New Britain Province is a seismically active area and experiences frequent earthquakes. Global WitnessActive volcanoes lie just across a harbour from the provincial capital Kokopo

"Impossible" to sell

With Indian tariffs on PNG palm oil so high in 2019, selling legitimately to the country in this period appears to have been economically unattractive.

According to UN Comtrade data, during 2019, India imported more than 6.6 million metric tons (mt) of crude palm oil, of which 1.7 million tons came from Malaysia.

By comparison, a mere 11,346mt was declared as coming from Papua New Guinea, despite its burgeoning plantations.

This illustrates how rare legitimate palm oil sales between Papua New Guinea and India were during this period compared to those from Malaysia.

Global Witness spoke to two palm oil industry experts in India.

One said it was “impossible” to import from PNG because of the significantly higher tariffs compared to Malaysian palm oil.

Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, an investigative journalist, author and the former editor of the academic journal Economic and Political Weekly, said: “If the customs duty on oil from Papua New Guinea is higher than the oil imported from Malaysia, and given the fact that Papua New Guinea is geographically located further away from India than Malaysia, the landed price of oil from Papua New Guinea would be substantially higher than oil imported from Malaysia.

“Since private businesspersons would like to maximise their profits, it is logical that they would not want to purchase oil at a higher price from Papua New Guinea.”

It would appear, therefore, that ENB found a dishonest route to marketing its product in India profitably.

Overall, then, Global Witness’s analysis found that palm oil shipments from PNG to India were indeed made in 2019, and there are serious grounds for believing this was undeclared.

And this would likely have been of financial benefit to Mr Tan and ENB, by opening up their product to a market that tariffs rendered otherwise unprofitable.

ENB categorically denied any involvement in tax evasion and said it “has and continues to proudly market and sells all palm products it ships and sells as of Papua New Guinea origin.”

It added: “ENB Trading & Shipping Pte Ltd has been dormant since incorporation, without any business activities since day one. Your allegations are entirely inaccurate.

“ENBRG has always done business with integrity, and we hold ourselves to high ethical standards.”

There is no suggestion that Ruchi Soya, to whom the Chem Peace consigned the crude palm oil in January 2019, was complicit in this alleged scheme.

But it should carry out due diligence and not allow palm oil tainted by deforestation into its supply chain.

Checking the origin of its purchases is a basic step. If Global Witness is able to find out this information, major companies could too.

Ruchi Soya did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

It should be noted that commercial records show that in 2020, ENB Trading Ltd was again named on shipments of palm oil from PNG to India.

If an illicit scheme was in operation in 2019, perhaps the ENB group had decided to bring it to an end.

But Mr Tan’s admission to an undercover Global Witness reporter, married with clear evidence that ENB palm oil was shipped to India from PNG that year, with no trace of such deliveries on trade databases or port records, means there are clear grounds for Indian authorities to investigate a possible tax scam.

Not far from the hotel where Mr Tan made his admissions, meanwhile, the tensions seeded by the palm oil industry had exploded in an incident far more frightening than the relatively placid world of white-collar crime.

Rural communities in PNG often need roads to access health care, schools, and markets, but the roads built by extractive industry can be worse than nothing. Ed Davey / Global Witness

Car chase and attempted murder

In September 2019, Doug Tennent, a Catholic lay missionary from New Zealand, drove to Warangoi, south of Kokopo, to inspect disputed land.

A legal officer for the Archdiocese of Rabaul, Mr Tennent spent years helping communities with land claims involving logging and oil palm development.

Too often, predatory companies pursue a policy of "divide-and-conquer" with local people to enable such projects.

Now the results of this policy would be turned on him.

After a local group had obtained a title over a parcel of land the Church claimed to have owned since the 1960s, Tzen Niugini planted more than 2,700 ha of oil palm there, according to Mr Tennent.

And when the churchman arrived in his small Suzuki car, his presence provoked an angry response, he alleged.

Mr Tennent tried to drive off, swerving around five men who tried to block his way. A car and a truck then gave pursuit in what had become a high-speed chase.

When the truck rammed his Suzuki from behind, locking his steering, it sent the car careening down a steep slope, rolling six times, Mr Tennent said.

He believes he was lucky to have survived the attack and described it to Global Witness as an attempted murder.

Contacted by Global Witness, the local police confirmed the near-deadly attack on Mr Tennent.

“They [Tzen Niugini] were not behind that,” said Mr Tennent.

While there is no suggestion that this incident was directed by Tzen Niugini, it is symptomatic of the conflicts the industry has provoked over time within and between communities.

“ENBRG has and continues to comply with all land laws in Papua New Guinea to acquire and/or develop land,” the company told Global Witness.

Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), touted by supporters as a green credential, is a palm oil certification scheme that covers 19% of global production, according to its own estimate.

The association says its objective is to advance the production and use of sustainable palm oil, in part via its eponymous certification programme.

Both oil palm growers and their customers can be certified under RSPO.

While the scheme has recently incorporated a no-deforestation requirement, it has repeatedly come under scrutiny for being ineffective due to poor implementation, lack of oversight, a sluggish grievance process and conflicts of interest.

Neither ENB nor RH companies in Papua New Guinea are RSPO-certified.

However, many of their recent big-name clients are (see “Household name buyers” below).

This results in ENB and RH palm oil finding its way into RSPO-certified supply chains, casting further doubt on the scheme’s validity.

Under RSPO’s "Mass Balance" system of certification, palm oil that violates RSPO’s own standards can still be sold as “certified”.

This scheme means if a trader buys 5,000t of certified and 5,000t of non-certified palm oil from a plantation like ENB’s, it is allowed to mix the oils together and sell 5,000t of it onwards with Mass Balance certification, even if some of that oil is from an uncertified and harmful site.

This policy completely undermines the scheme and could mislead consumers.

Consequently, buying some palm oil from plantations engaged in large-scale deforestation and with dangerous working conditions is not a violation of these companies’ commitments under their RSPO certification.

It should be.

An RSPO spokesperson said: “It is our mission to ensure the sustainable palm oil sector respects biodiversity, natural ecosystems, local communities, and workers’ rights and safety.

“All RSPO members are required to make time-bound commitments to only purchase certified sustainable palm oil (CSPO).”

The organisation described the Mass Balance model as a way for companies to begin to do this.

It pointed out that mills producing Mass Balance palm oil must check that the oil palm fruit they process has been grown legally.

Environmental cost

New Guinea has the highest plant diversity of any island on Earth. Global Witness

The ENB Resources Group is thus implicated in bribery, violence and tax evasion. But what of the environmental harms?

Between 2002 and 2014, a greater proportion of forests on New Britain were clear-cut than in any other part of PNG.

Global Witness’s analysis now indicates ENB has cleared thousands of hectares of forest on the island.

New Britain is part of an "Endemic Bird Area", home to 14 species of bird found nowhere else on earth. Some are highly dependent on lowland forest such as that found on the island, putting them at risk of extinction.

ENB operates two plantation sites in East New Britain. Part of one plantation, operated by ENBPOL in the Gazelle District, was cultivated by smallholders growing cacao and coffee – until ENB bulldozed their trees to plant oil palm (see below).

The other, operated by Tzen Niugini in the island’s Pomio District, was formerly rainforest.

At that Pomio concession, Global Witness calculates some 18,900 ha of forest was destroyed between 2007 and 2019.

(See Methodology below) ENB exported about 800,000m3 of valuable tropical timber from this project.

Together, these findings paint a picture of a company that is willing to defy national and international law, and destroy highly biodiverse, culturally critical forested landscapes to produce its palm oil.

ENB told Global Witness it complied with all forestry, environmental and land laws in PNG and denied participating in any illegal activity.

International financing

Large-scale industrial agriculture is a capital-intensive industry, and ready access to capital is thus a pinch-point on the ambitions of destructive corporations such as ENB.

That is why Global Witness is campaigning for the UK, US and EU to compel its banks and investors to screen out companies engaging in deforestation from their client base.

During this investigation, Global Witness obtained first-hand testimony as to how effective this would be.

ENB chief executive Mr Tan told our undercover reporter when it came to funding, “that alone is a constraint to our expansion ...”

He continued: “We are not able to expand, not because we are not, not because our appetite are [sic] small, just because we feel that … financial resources are limited ...”

Irregularities and abuses in land and forest-related industries in Papua New Guinea are extensively documented, routine and severe.

Despite this, Global Witness has discovered the Malaysian financial powerhouse Malayan Banking Berhad (Maybank) has chosen to bankroll ENB’s activities.

Maybank itself is owned in part by a host of well-known financial names in the UK, US and EU.

These institutions are thus enablers of the crimes and abuses detailed above.

Documents filed with the PNG Investment Promotion Authority reveal that in July 2015, Maybank Group subsidiary Maybank Islamic Berhad inked an agreement with ENBPOL to make as much as US$40 million of financing available to the company group.

The documents refer to ENBPOL’s revenues from “plantation land”.

This comes as no surprise. Maybank is one of the world’s largest palm oil financiers, pouring US$3.9 billion in loans and underwriting services into the sector between 2010 and 2016, according to an analysis published by Tuk Indonesia and Profundo.

It has been previously criticised for financing clients involved in land grabbing, devastating vegetation-clearance fires in their concessions, development on peatlands, and lack of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) in dealings with local and Indigenous communities.

Logging or palm oil projects are often in hard-to-reach places. Ed Davey / Global Witness

Maybank’s 2020 sustainability report refers to a framework for assessing risks of financing palm oil, but Global Witness has been unable to find it or the bank’s overarching ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) policy.

This raises the question of how communities are meant to avail themselves of rights under a policy that they can’t even see.

According to Maybank, however, it requires its palm oil customers – in this case ENB – to comply with NDPE (No Deforestation, Development on Peatland and Exploitation of Indigenous and local people and workers) policies.

It is unclear how or if this policy is implemented.

Global Witness’ investigation finds that by financing ENB, Maybank has enabled the company’s abuses, from deforestation to the apparently corrupt acts described by its senior staffers.

While we do not know how much money Maybank made on its deal with ENB, the bank certainly expected to profit, and entered into the deal despite the well-documented risks of illegality and serious harms endemic to the PNG land and forestry sectors.

“Maybank is fully cognisant of the environmental, social and governance impacts associated either directly or indirectly with the activities within the countries we finance and specifically … the issues associated with deforestation, improper governance, labour as well as human rights,” the bank said.

“We would like to stress that the Group is cautious in its approach when engaging or financing companies that may have a negative impact on the environment and communities.”

Maybank said it engaged clients to “ensure alignment with sustainable practices,” and high-risk companies were required to undergo additional assessment.

Where clients fell short, business relationships are “re-considered.”

The bank went on: “Maybank is unable to confirm or discuss any alleged banking relationships we may have, or have had with any organisation, owing to banking secrecy laws.

“We, do however, wish to reiterate that Maybank in 2015 had disposed of our banking subsidiary in Papua New Guinea.”

Maybank did not respond to Global Witness’s allegations regarding ENB and Rimbunan Hijau (see below) operating without community consent.

The bank said that it intends to publish its NDPE commitments and an ESG policy soon.

“Maybank is committed to playing our role in helping countries and companies … to grow the economy in a sustainable manner, whilst remaining responsible to local communities and the environment,” it said.

Rinsing cookware in a river in East New Britain Province. Community landowners downstream from palm oil plantations have described polluted water and chemical run-off. Global Witness

International financiers

Maybank’s shareholders include some of the globe’s most powerful financiers. These include two subsidiaries of the world’s largest asset manager, BlackRock.

Additional backers include the giant California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), and Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), the manager of Norway’s oil fund, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund.

The Vanguard Group, Inc. and Dimensional Fund Advisors, LP also appear among the top shareholders, as does the Netherlands-based Robeco Institutional Asset Management B.V.

UK-based Pyrford International Limited is also a shareholder.

By investing directly in Maybank, these funds and asset managers are partly responsible for the abuses carried out by the bank’s customers that its financing has enabled.

“Pyrford International takes its ESG responsibilities very seriously,” the investment firm said, adding that it had been a signatory to the UN Principles on Responsible Investment (PRI) since 2014.

Pyrford said it was part of BMO Global Asset Management, which it called “an industry leader in terms of responsible investing.”

The fund said it had raised Global Witness’s concerns with Maybank.

Nevertheless, it declined to commit to pressing Maybank to investigate Global Witness’s findings.

Dimensional Fund Advisors did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Slipping through the cracks

Some of these financiers have developed policies or principles that should limit their investing in deforestation.

CalPERS, for example, says that companies should disclose and manage environmental risks, including deforestation.

Robeco boasts it is a signatory to over 60 sustainable investing memberships, statements and principles.

The asset manager states it will exclude palm oil producers that have less than 20% of their land certified by RSPO from its funds.

But it does not exclude the financiers of palm oil – meaning the likes of Maybank can slip through the cracks.

CalPERS acknowledged holding millions of shares in Maybank, as well as in RHB Bank Berhad and Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation.

But, a spokesman said, “We don’t have insight or comments about the material contained in [Global Witness’s] letter,” adding that these investments were passively managed as part of an index fund.

Robeco said: “Regarding our engagement with Maybank, we are part of the PRI working group on palm oil and deforestation … that has actively engaged Maybank on strengthening their no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation policy since 2019 to reduce the negative impact on biodiversity they are exposed to as one of the largest financiers of the palm oil industry.”

The firm claimed it actively addressed the risk of deforestation in its investments with an “active ownership strategy.”

“As a responsible investor, NBIM has focused on climate change and human rights issues for more than ten years,” the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund manager said.

“We expect companies engaged in activities with a direct or indirect impact on tropical forests to have a strategy for reducing deforestation from their own activities and from their supply chains,” and to conduct human rights due diligence.

“Since 2018, we have proactively engaged with banks in Southeast Asia regarding their policies for lending to companies that contribute to deforestation,” NBIM said.

“We urge the banks to strengthen their due diligence and to report on climate and deforestation risks.”

NBIM said it did not provide information about its engagements with individual companies.

Stewardship issue

For their part, BlackRock and Vanguard have voted against almost every shareholder resolution to halt deforestation by the companies in their portfolios since 2012.

These asset managers are facing growing pressure on their poor record on deforestation, land rights and Indigenous rights issues.

Approached for comment, BlackRock said: “Palm oil production is an example of a particularly complex investment stewardship issue.”

It pointed Global Witness to a 2021 publication that said BlackRock encourages companies to disclose their plans for sustainable use of natural resources.

“As an asset manager, BlackRock cannot substitute one company for another company or exclude any particular companies from the indices selected by our clients,” a spokesperson continued.

“We focus on engaging with companies’ management teams and boards to understand how companies are managing sustainability risks.”

Vanguard said it took the concerns raised seriously and would incorporate them into its analysis and monitoring of companies with direct and indirect business exposures in the PNG region.

“We have engaged on this topic and associated matters such as deforestation,” it said, noting that it participated in the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative.

“When a company’s products, services, or practices pose a risk to its employees, customers, and the communities where the company operates, it can manifest into material reputational, competitive, legal, and regulatory risks that can affect long-term shareholder value.”

The severity of the cases that Global Witness have uncovered raises disturbing questions of if, and how, laws or norms relating to due diligence required to avoid financing linked to companies engaged in illegal activities have been broken.

They also reinforce the need for countries that import, use or finance forest-risk commodities such as palm oil to recognise that company self-regulation has failed.

Clear requirements are needed for businesses, including finance, to undertake adequate due diligence on deforestation, the lack of FPIC, and related human rights abuses.

Such laws are currently being proposed in the EU and UK, and potentially the US – and Global Witness is campaigning to ensure that the finance sector is not exempted from these provisions.

Land has been cleared for oil palm plantations in the Bainings region of East New Britain, Papua New Guinea. Global Witness

"Severe assault", hundreds evicted

There was more than enough evidence of problems to have steered Maybank away from financing the ENB group.

A legal battle involving ENB in the Gazelle district of East New Britain Province illustrates Maybank’s disregard for palm oil’s impact on communities.

Landowners and settlers there told the PNG National Court they had not known about nor agreed to a 99-year agricultural lease granted over their land for oil palm development.

A local government official who objected to the project said he was “severely assaulted” by supporters of the project in retaliation.

The land had previously been included in a US$50 million World Bank project to improve the livelihoods of smallholder coffee and cacao growers.

Global Witness has now seen unpublished documents indicating that 120 households that benefited from this scheme were forcibly evicted, with their homes, gardens and equipment destroyed.

In 2017, a Global Witness team visited the area and interviewed some of those landowners objecting to the project, who alleged an entire village had been evicted, leaving people internally displaced.

Hundreds of families not supported by World Bank funds were also allegedly evicted, while dozens more families were affected by ENB’s activities, with their water sources or gardens damaged.

At an average family size of six, this would mean ENB’s actions affected the lives of well over one thousand people.

In August 2016, the judge found for the plaintiffs, ruling that land was “hijacked from appropriate land owners” in breach of the Land Act and the Constitution.

Nevertheless, during the trial, in December 2015, ENB had already awarded a contract to build the group’s Narangit palm oil mill in Gazelle District.

This mill is now producing palm oil sold around the world, while the families who lost their land have reportedly received no compensation.

The case had been in progress since 2012, three years before the Maybank deal with ENB. Proper due diligence by the bank on this case alone should have precluded it from lending to the group.

The terms of its financing required ENBPOL to check and ascertain that no pending litigation against it might have a “material adverse effect” against the company’s operations.

Global Witness asked both parties if ENBPOL disclosed the lawsuit to Maybank, but did not receive a reply.

Roadside sign describes a project under the World Bank-funded Productive Partnership in Agriculture Project, East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea. Global Witness

Reached for comment, the World Bank said it had raised concerns with the PNG government when land incursions impacting farmers in its project area were reported in 2015.

It said 95 cocoa blocks were destroyed, and the bank had communicated this to the government, which issued a stop work notice to ENB.

“Although the Productive Partnerships in Agriculture Project closed in May 2021, we remain concerned by the land incursions in East New Britain,” the bank said.

“In preparing further PNG agriculture sector projects, the World Bank supported the Government of PNG to put in place strategies to help prevent similar issues from occurring again.”

ENB wrote: “Squatters can be evicted from State Land if they are residing there without the authority or the permission of the registered Lease holder.

“This is not unusual and both the District Court and National Court can issue eviction Orders [sic] where squatters refuse to move.

“Their only ‘right’ is the right to receive reasonable notice to vacate. To our knowledge, ENBRG has not participated in any forceful evictions as claimed by you.”

“All labourers of the previous cocoa and copra plantation and persons living near the plantation have been given employment opportunities to work at the oil palm estates,” the company also said.

As we shall see, this litany of offences has not barred the ENB Group’s palm oil from making its way into a global array of goods, made by companies such as Colgate-Palmolive and Nestlé, whose products you likely have at home right now.

But ENB is not the only malevolent actor in PNG’s palm oil industry.

Global Witness can also reveal that the activities of a far more influential company are resulting in an ongoing and avoidable human tragedy.

Special Agriculture and Business Leases: A toxic legacy

ENB, RH (Rimbunan Hijau Group) and Bewani (Bewani Oil Palm Plantations Ltd) all obtained access to land through Special Agriculture and Business Leases (SABLs).

This now-infamous system allowed the control of over 50,000km2 of PNG land to be wrested from Indigenous communities and transferred to foreign companies.

The PNG Forest Authority issued forest clearance authorities (FCAs) alongside SABLs, allowing companies to flatten rainforests and export timber worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

In 2013, a government commission into these leases found the vast majority of SABLs that it published findings for violated PNG law – typically by ignoring communities’ constitutional land rights.

Yet, for reasons that have never been made public, many leases the commission reviewed were not included in its final report, including all of those in East New Britain Province – which included the ENB Group and RH leases.

Rimbunan Hijau Group

Total forest destroyed, 2011-2019: 24,600 ha

Global Witness calculates that Rimbunan Hijau deforested ~24,600 ha in East New Britain between 2011-2019. Shown: mosaic imagery from 2007-2010 (before); image from 2021 (after)

Rimbunan Hijau Group (RH) [1] – the name means "Forever Green" – is a sprawling global business empire with interests in forestry, palm oil, plastics manufacturing, mining and the media.

Its founder, Malaysian businessman Tiong Hiew King, is listed on Forbes’ Richest 50 List for Malaysia, with an estimated net worth, in 2021, of US$1.3 billion.

In Papua New Guinea, RH owns one of PNG’s airlines, The National newspaper and a plush hotel in the capital Port Moresby.

It is logging several areas throughout the country and operates palm oil plantations in Pomio, East New Britain Province.

The logging and plantation projects have been the source of protests for many years from communities who say RH has exploited them and their forests.

Global Witness has previously reported community landowners’ allegations that its access to Pomio land was obtained through fraud and forgery.

RH denied these claims.

RH did not respond to Global Witness’s repeated requests for its comment for this report, including a request hand-delivered to its headquarters in Papua New Guinea.

RH subsidiary Gilford Ltd acquired FCAs for three leased areas in the Pomio District of East New Britain Province in 2010.

Since then, the company has devastated the coastal rainforest where it operates, clear-cutting tens of thousands of hectares that local communities had relied upon for sustenance.

In 2017, Global Witness revealed RH had cleared almost 210km2 of rainforest and exported about 1.2 million cubic meters of timber – worth about US$122m – from its leased areas in East New Britain Province.

We calculate that a further 30km2 has now been cleared and another 100,000 cubic meters of timber shipped out (see Methodology below).

Communities in the Pomio district of East New Britain Province have calculated that over the lifetime of the leases, they will suffer more than US$730 million in damages due to this destruction.

This calculation, made by 17 communities, includes among other items the loss of timber exported by RH, lost subsistence agriculture and market income, and the near-total destruction of the environmental goods and services provided by the forest.

Global Witness can now reveal new evidence of serious human rights abuses and negligence by RH on its oil palm plantations.

These have led to a spate of serious injuries – some life-changing – and tragic and preventable workplace deaths.

It is a human cost to RH’s wealth and influence that should appal potential investors and business customers.

Permanent injuries

A 2019 study found that the over 1 million oil palm plantation workers globally are at risk of suffering from bone and muscle injuries, chemical exposure, infectious diseases including malaria, and depression and anxiety.

Workers, especially women and girls, are also subject to sexual assaults and violence.

By any measure, palm oil labour is stressful and often dangerous work. It is therefore especially important for plantations to maintain robust safety standards.

Global Witness began investigating worker safety on the RH plantations in East New Britain after being tipped off by two former employees that a catalogue of preventable deaths and serious injuries were taking place.

“It’s very bad,” one employee said. “[Workers] live in a house with no lighting, no water. Compliance? Zero.”

Asked what safety equipment the company provided, he said: “They give them boots but then deduct it back from their pay. If you ask for it, you get it, but you have to pay for it.”

Pomio communities depend on their forests for their livelihoods and traditional ways of living. Global Witness

At least 12 people died on the RH plantations between 2012 and 2020. Eleven of these were RH employees, and one was an employee’s school-aged dependent.

Over the same time span, a dozen more were involved in serious accidents, some life-altering.

(See Methodology below for an explanation of our research methods. A full list of the deaths and injuries Global Witness has catalogued is in Appendix 1.)

The deceased workers died from blunt-force injuries, falls or unknown and un-investigated causes.

Many of the deaths and accidents stemmed from motor vehicle accidents on the plantation, where heavy trucks laden with fruit bunches or logs share the rough tracks constructed by RH with pickup trucks, motorbikes and workers on foot.

Global Witness believes it is the first organisation to publish these findings.

Papua New Guinean health and safety consultancy Niugini Environment Management Services (NgEMS) reviewed the findings for Global Witness.

Principal Tony Aromo has over a decade’s experience in the palm oil sector in PNG and served as a technical expert on the working group developing nationally appropriate standards for RSPO.

Some readers may find the following examples upsetting.

Father-and-son tragedy

On the night of 28 November 2014, Leo Kaukau, a forklift operator at an RH subsidiary, cooked dinner for himself and his 11-year-old son Ronald using water from a container that had held chemicals used for killing grass in the plantation.

Paraquat and glyphosate, herbicides used by the oil palm industry in PNG, are both toxic to humans. Just one sip of paraquat can kill, producing vomiting and kidney and respiratory failure.

Felix Tau, Leo’s brother, said the father and son began vomiting within 10 minutes into their dinner.

Leo Kaukau died on the way to a health clinic the next morning, while his son died shortly thereafter. No autopsy was performed, nor inquest held.

PNG’s Employment Act provides penalties for employers who fail to provide their housed workers with safe drinking water. To avoid such deaths, hazardous chemical waste must also be properly disposed of.

In its review of the evidence for Global Witness, NgEMS said that under guidelines established by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), used pesticide containers should have been triple-washed and then made unusable, to prevent exactly such a tragedy from occurring.

The victims’ family has reportedly received no compensation for their deaths.

Another fatality occurred on November 11, 2020. Father of four Anton Kelal, who had worked for RH subsidiary Sinar Tiasa since 2011, was a passenger in a dump truck on the plantation.

Five witnesses saw the truck speed up and Mr Kelal fall from the cab, hitting his head and dying instantly. His brother, Lawrence Lapuli, was among the witnesses.

Mr Kelal’s death certificate indicates his brain was contused and both his lungs collapsed.

According to his brother, RH provided PGK5,000 (about £1,000) for burial costs, but has not otherwise compensated Mr Kelal’s family.

His children are being taken care of by extended family members.

Noting that there was evidently no motor vehicle accident report done, NgEMS’ review of this case recommended a police investigation into the accident.

Reckless driving may be a violation of the PNG Road Traffic Act.

“Allowing employees to drive negligently without due care and attention for other and company property show[s] a total lack of duty of care,” NgEMS wrote.

“The ultimate responsibility and accountability [for] employees’ negligence lies with the top management of the organisation.”

Amputations, chemical accidents

Global Witness compared these tragedies with the safety record of two comparably-sized plantations operated by a different company in Papua New Guinea.

In stark contrast to the lack of public reporting of incidents at Rimbunan Hijau operations, accidents at New Britain Palm Oil Ltd (NBPOL), one of the RSPO-certified palm oil companies operating in PNG, are publicly reported.

Company reports show that between 2010 and 2020, one worker died at the company’s Higaturu plantation, and three died at its Milne Bay plantation.

Both of these sites employ roughly the same number of workers as RH’s Pomio operation.

(For more details, see Methodology below).

This suggests health and safety measures can be put in place to improve conditions on the RH plantation, which the company has failed to do.

Logs harvested from Papua New Guinean forests can exceed a meter in width. Global Witness

Workers’ injuries on the RH plantations include amputated fingers, broken bones, and the impacts of chemical exposures and vehicle accidents.

Almost without exception, accident survivors also seem to have gone financially uncompensated.

Truck driver Charles Sai was 22 years old on 1 March 2013, when a log slipped from a pile and hit him on the neck.

The logs loaded onto ships for export from PNG can measure over a meter in diameter and 15 meters in length.

This one caused ligament damage and fractured three vertebrae, including the C6 vertebra – a severe injury that risks paralysis and nerve injury. A medical assessment concluded the use of Mr Sai’s back had been reduced by 80%.

Records seen by Global Witness indicate he received no recompense – and even had to pay PGK250 (about £50) for a copy of his own workers’ compensation report. Mr Sai said he had to pay for his own medical expenses as well, adding that he felt used by the company.

In its assessment of this case, NgEMS noted that East New Britain is a highly seismically active area, with frequent small earthquakes. Stockpiles of logs must therefore never be raised too high and must be appropriately barricaded and signposted for the safety of workers and passersby.

According to NgEMS, there is no indication that such simple precautions were taken. If they had, Mr Sai would almost certainly never have been injured, NgEMS said.

Unreported tragedies

Only seven of the 12 deaths Global Witness documented seemed to be recorded in the governmental Office of Workers Compensation (OWC) database when this report was written[2].

And only seven of the 12 serious injuries Global Witness documented appeared.

Employers who fail to give notice of employees’ injuries or deaths are guilty of an offence under the PNG Workers’ Compensation Act.

An official at the East New Britain Provincial Health Authority declined to discuss the incidents on the phone, saying they “might get into trouble.”

RH did not respond to Global Witness’s request for comment.

It did not even issue a statement of regret for the loss of life on its plantations, nor sympathy for the bereaved families or those who have suffered life-changing injuries.

In addition to accidental death and injury on its plantations, RH is also linked to a particularly shocking case of human rights abuses.

"Inhuman" treatment

In October 2019, Global Witness met Anthony Salmang, a Pomio landowner who described the impact the RH operations have had on his community.

“We always get fresh fish from the water,” he said. “In the bush, we hunt for animals like wild pigs. They are precious in our life. We live by the nature.”

But this way of life has been obliterated by the company’s activities.

“Now [the water] is full of chemical activities, fertiliser that flows down the river, and all the corals are killed,” he said. “It really changed our life. We lost most of our traditional livelihoods, like sacred sites.”

He added: “Empty, I can use that term, empty, because all those things are gone. We cannot bring them back."

Allegations of RH’s ruinous impact on communities’ environments are nothing new.

Local government official and outspoken Pomio landowner Paul Palosualrea Pavol, who won the Alexander Soros Award for his environmental activism in 2016, also told Global Witness the company’s forest destruction has driven away wild animals.

He said: “The concern is that our children do not know hunting skills and most of them don't know what cassowary looks like and how a wild pig reacts against a hunter.

Pavol said water in the area was “polluted” and fish had been caught that tasted of “oil and fuel.”

Now [the water] is full of chemical activities, fertiliser that flows down the river, and all the corals are killed

But when Mr Salmang and other landowners tried to photograph RH’s environmental devastation, armed police swooped.

They allegedly forced him and 64 other people from villages in the Pomio area affected by RH’s activities into a single metal shipping container that doubled as a holding cell at the plantation camp.

There, Mr Salmang said, they were held tightly packed for five to six hours, through the height of the tropical sun – without water or access to toilet facilities.

“We were crushed inside,” he recalled. “There was no room for us to sit. You could not move. It was inhuman.”

Elderly men were among those allegedly locked up, not accused of any offence at that point: the incident could easily have been fatal.

Mr Salmang’s account has been by corroborated by Sarawak Report, which interviewed another of the 65 men held in a 2020 video report.

Although most were then released, nine remained in the container overnight, Mr Salmang recalled.

The next day, they were brought by boat to Kokopo, many hours’ voyage from their homes.

There, they were finally arrested on charges of interfering with police duties and jailed for two nights in a holding cell with between 60 to 70 men, he said.

RH made no comment on this incident.

Women waiting for transportation in East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea. Global Witness

Police terror

Accusations that RH uses the police to intimidate and violently attack communities objecting to their activities date back years.

In 2012, Mongabay reported RH-funded police “terrorised” communities in the Pomio area now developed for palm oil, beating people with sticks and fan belts and locking people in shipping containers for up to three nights.

These allegations from Pomio communities of police violence led to an independent fact-finding mission in 2013 organised by civil society and including members of the police and local government employees.

This found that police hired by RH subsidiary Gilford had forced landowners to sign logging consent forms under fear of death, and beat others with gun butts and tree branches.

The report concluded these “acts of assault did amount to serious indictable criminal offences.”

Previously, RH told Global Witness that a March 2017 police investigation found no evidence of malpractice at the sites and that local community members had “requested a larger police presence to maintain order as the area experienced strong economic growth.”

Multiple PNG Police Commissioners have forbidden officers to be stationed in logging camps across the country.

The fact that these edicts have been repeatedly issued points to their ineffectiveness.

In September 2020, the then-Minister for Police, Bryan Kramer, released a statement condemning the lack of integrity of the Constabulary.

“The very organisation that was tasked with fighting corruption had become the leading agency in acts of corruption,” he wrote, describing “a rampant culture of police ill-discipline and brutality.”

Global Witness repeatedly contacted the Royal PNG Constabulary for its comment on this report, but the police force did not comment.

These findings show that RH has committed grave human rights abuses and neglected the health and safety of its workers, leading to deaths and life-altering injuries.

RH did not respond directly to Global Witness, but it did send a response to one of its customers, the Mewah Group, regarding our allegations.

The company said: "The Sigite Mukus Integrated Rural Development Project has the full approval of Government and has been operating since 2011."

"Since project commencement, it already transformed [sic throughout] the lives of thousands of families in East New Britain.

"More than 4,000 people are directly employed by the project. Millions in royalties and development levies has been paid directly to landowner communities."

It said the project had constructed "hundreds of kilometres of new roads" and new and rehabilitated airstrips.

"National business entrepreneurs have been able to capitalise on the increased economic activity and improved infrastructure to open their own businesses.

"We have seen new trade stores and public transport vehicle businesses flourish.

"Families are now able to bring produce to market. Students can get to school more easily, and people seeking medical services can reach them without life-threatening delays."

RH said it had dedicated "significant funds" to a PNG malaria eradication initiative and had signed an agreement with the East New Britain provincial administration to support local aid posts.

The company called Global Witness "a group of economic vandals who do not care about the lives they destroy."

It claimed that the specific allegations presented in this report were presented out of context and "without any real basis."

RH said it abided by all relevant laws and regulations, recognised the socio-economic needs of forest communities, and took environmental obligations seriously.

Consumers may be shocked to learn products they are consuming – from brands such as Kellogg’s and Danone – are linked to the abuses this investigation has uncovered.

But as we will see below, tracing the palm oil stream leads directly from RH’s dangerous and repressive operations to huge commodity traders and a multinational consumer goods company that claims to have its brands in more homes than any other company worldwide.

Unequal burdens

The impact of harmful palm oil companies is not felt uniformly – women feel the burden most.

Land in East New Britain Province is inherited through matrilineal custom, from mother to daughter.

Despite this, women have increasingly been excluded from decision-making over their own land as logging and palm oil development have encroached on the province.

The loss of the forest itself has brought additional tribulations.

PNG women typically do the lion’s share of gardening and produce most of the country’s crops, while also taking care of children and the family.

Access to clean drinking water is very poor, and women and girls in rural communities are often tasked with collecting water from springs and other waterways.

The destruction of forests, where women manage their gardens and which provide clean freshwater, makes these already challenging tasks significantly harder.

Following the money

Much of this destruction might have been prevented if RH did not have access to big finance.

Global Witness has now uncovered documents showing RH companies secured a loan for up to US$300 million from a consortium of major Malaysian banks in 2012.

A document filed with the Investment Promotion Authority names a consortium of banks including Maybank, Singapore’s Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (OCBC Bank), and Malaysia’s RHB Bank Berhad (RHB) entities as being behind the deal.

The financing was provided to RH’s subsidiary Gilford, which holds the clearance authorities for the plantation areas.

The deal was struck as clear-felling there began to accelerate.

Logging from SABLs in Bairaman, Papua New Guinea. Global Witness

Maybank’s lending to the palm oil industry is well-established (see its response to Global Witness in "International Financing" below).

In 2015, Maybank (PNG) Ltd, one of the banks in the $300 million deal, was acquired by Kina Bank, an arm of Kina Securities Ltd.

The bank, whose red, white and orange logo is a familiar sight in PNG’s capital, is listed on both the national and Australian stock exchanges.

Kina Bank said that it had no financing arrangements with RH.

It said the Asian Development Bank, as a major shareholder, had conducted a detailed ESG audit of all the issues Global Witness had raised with Kina, “to ensure the business complied with the highest standards in this regard.”

Asked whether the 2012 agreement with RH had matured before or after Kina’s acquisition of Maybank (PNG) Ltd, Kina did not respond.

Singapore’s Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation, Ltd is the second-largest financial services group, by assets, in Southeast Asia.

The bank says it “will not engage in or knowingly finance any activity where there is clear evidence of immitigable adverse impact to the environment, people or communities.”

It requires borrowers to have their own policies against deforestation.

The bank’s Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) risk assessment process, implemented in 2017, requires it to check their customers’ management of ESG risks like deforestation and occupational safety at least annually.

RH’s actions in PNG should have been scrutinised several times over by the time this report was written.

That OCBC should finance RH illustrates perfectly why internal policies are not sufficient to prevent financing of the kind of abuses detailed in this investigation.

Contacted by Global Witness, OCBC Bank said that banking regulations prevented it from discussing individual clients.

“However,” it wrote, “we require our borrowers to have safeguard[s] against deforestation and to take into consideration social issues such as child/forced labour, occupational health and safety as well as any resettlement of affected communities in our assessment.”

Sustainability journey

The bank did not say whether it had checked RH’s management of environmental and social risks, as required under its policy.

“We are committed to this sustainability journey,” it added.

A third funder, RHB Bank, controls dozens of commercial and investment banking entities throughout Southeast Asia. This includes two banks in the consortium that provided the loan to RH’s subsidiary Gilford.

It did not formalise a policy framework requiring social and environmental sustainability of its customers’ operations until 2019.

This framework states it is “integrating ESG factors and risks” into its business and seeking to minimise “negative impacts to the environment and society.”

The bank’s involvement with the loan makes a mockery of this commitment.

RHB did not deny having financed RH.

The bank said: “At RHB, we formally embarked on our sustainability journey in the fourth quarter of 2018 and institutionalized it in 2019.

"Since then, we continue to take a practical approach and have progressively embed [ESG] practices or considerations into our business and operations as part of our overall sustainability journey.”

The bank said that under its ESG Risk Assessment tool for the palm oil sector, customers with a plantation size of over 100 acres were required to obtain sustainability certification, abide by the Malaysian Palm Oil Board’s (MPOB) codes of good practices, and “avoid virgin forest, aboriginal or heritage land.”

Yet as with ENB’s financing, the money trail does not only originate in Malaysia – for these banks count among their major shareholders some of the biggest names in global finance.

These include many of the same investors as Maybank’s, such as BlackRock, Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM) and the Vanguard Group.

Many of these financiers’ names appear repeatedly behind the flows of money enabling the wholesale destruction of tropical forests, despite their own investment guidelines acknowledging climate risk.

NBIM’s 2019 annual report said it “urged [banks] to strengthen their due diligence and to report on climate and deforestation risks.”