Everyone knows the Amazon is in crisis. But next door, another ecological catastrophe is unfolding in the Cerrado savannah, which is being destroyed to feed the world’s appetite for beef

South of the world’s largest rainforest lies the Cerrado savannah, dubbed the "upside-down forest" for the sprawling roots which help its trees survive droughts and lock up carbon.

Like its neighbour the Amazon, it is being destroyed to feed the world’s appetite for beef – and it is major financial institutions who are bankrolling the bulldozers.

Deforestation in the Amazon is falling, but in the Cerrado it rose to record levels last year – increasing by 43% from 2022.

New research by Global Witness reveals who is behind much of the destruction.

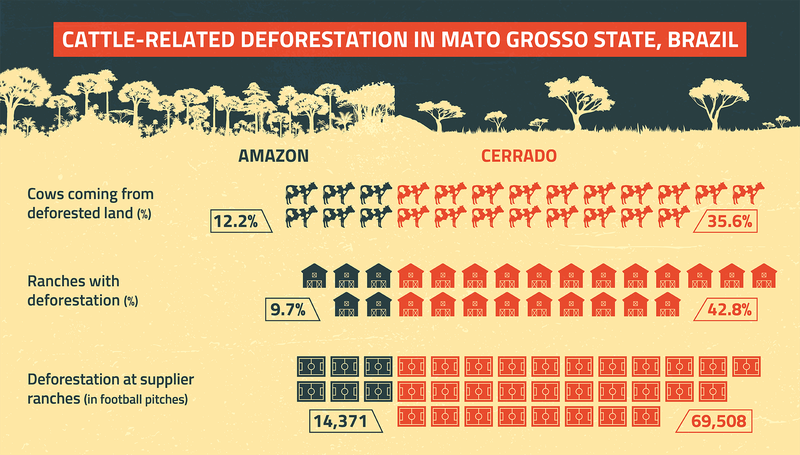

Using public data, we investigated ranching in Brazil’s cattle capital, Mato Grosso state, which straddles both Amazon and Cerrado biomes.

In line with broader deforestation trends in the region, we found Cerrado clearances far outpaced those in the Amazon.

The Cerrado savannah is home to more than 11,000 plant species

The Cerrado crisis: Brazil's deforestation frontline

Download ResourceBrazil’s three biggest meatpackers – JBS, Marfrig and Minerva – play a key role in this environmental devastation.

Global Witness found these global companies have considerable illegal deforestation in their supply chains.

A combined area of forest bigger than Chicago was felled within ranches supplying the beef firms with bovines across Mato Grosso – 99% of it illegally, through a lack of the permits required for deforestation under Brazilian law.

Deforestation linked to the Brazilian trio was nearly five times greater in the Cerrado area of Mato Grosso than in its Amazon territory, where in the latter the companies have legal agreements for monitoring their supplies.

One in three cows (36%) that the companies bought from the Cerrado within Mato Grosso came from farms with illegally deforested land.

JBS was linked to the most farms with deforestation in both biomes.

All three companies dispute Global Witness’ findings and said they are compliant with Brazilian law on deforestation and with their own individual supply chain agreements with Brazilian authorities.

Global Witness found that beef demand in both the UK and EU are playing a part in the region’s deforestation.

By analysing trade data, we found that over the past five years the UK imported an average of 1,756 tonnes per year of beef products from Mato Grosso state.

Similarly, as of 2018 and 2019, at least 14 slaughterhouses owned by JBS, Marfrig and Minerva in Mato Grosso have authorisation to export to EU countries.

This global trade of deforestation-linked beef is partly underpinned by western finance. Global Witness analysed commercially available market data and found major American, British and EU financial institutions are contributing to the widespread environmental abuses through their financial support.

Market juggernauts including Barclays, BNP Paribas, HSBC, ING Group, Merrill (formerly Merrill Lynch) and Santander have together underwritten billions of dollars in bonds that help the big beef firms borrow money and grow.

Financial heavyweights such as The Vanguard Group, BlackRock, Capital Research Global Investors, Fidelity Management & Research Company, T. Rowe Price Associates, AllianceBernstein and Compass Group offer further support through owning shares in them.

Unlike its Amazon neighbour, the Cerrado is relatively unprotected by laws and voluntary agreements around the world.

Significantly, it currently falls outside the scope of the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), the bloc’s ground-breaking law banning the trade in commodities produced on deforested land.

Global Witness’ research underscores the urgent need to address deforestation in the Cerrado, and hold accountable an industry that is driving the destruction of forests and other wooded lands crucial to the planet’s climate.

Two-thirds of deforested land in the Amazon and Cerrado is used for cattle pasture, according to a 2020 study.

The findings also provide fresh evidence that global financial centres must bring in mandatory due diligence checks against funding deforestation, and strengthen financial regulations to end their firms’ role in tropical forest destruction.

"Upside-down forest"

The Cerrado forest savannah covers about one-fifth (22%) of Brazil’s territory and is home to some of the world’s greatest biodiversity, including over 6,000 tree species.

It is nicknamed “the upside-down forest” because of the deep, extensive roots its plants use to survive seasonal droughts and fires.

Such subterranean riches mean the savannah stores about five times more carbon in roots and soil than above ground.

In 2017, the Cerrado was said to hold 13.7 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, which is more than China released in 2020. However, large scale deforestation in recent years is likely to have significantly affected this storage.

The Cerrado’s importance for the Earth’s climate cannot be overstated. The campaign group WWF has said that if this critical biome continues to be destroyed then the UN climate target of liming global heating to 1.5°C will be put out of reach.

The immense, dry, open-canopy woodland also has great social importance. Many Indigenous peoples and traditional communities live here or use its natural resources, including Quilombolas (descendents of runaway slaves) and Ribeirinhos (riverside dwellers).

While the Brazilian Amazon’s annual deforestation rate fell by half in 2023, the Cerrado’s increased by 43%.

Separate data from July 2021 to August 2022 had already shown deforestation was up by 25% from the previous 12 months, totalling 10,700km2. Of this, losses in Mato Grosso state accounted for 7%, or 740km2.

Cattle capital

Located in central-west Brazil, the state of Mato Grosso includes three significant biomes: Amazon rainforest in the north, with Cerrado forest savannah stretching to a southernmost section of Pantanal wetland.

This ecological mosaic makes the state an ideal place to compare deforestation linked to the cattle trade in the Amazon and the Cerrado.

The consequences of environmental devastation here have global implications for climate change and biodiversity conservation.

Mato Grosso has the largest cattle herd of any Brazilian state with some 32.8 million cows, or nine per inhabitant.

These bovine battalions mean Mato Grosso plays a crucial role in the global beef trade.

The state is one of Brazil’s biggest beef exporters. Exports in 2022 were worth a staggering $2.75 billion, mostly going to China ($1.9 billion).

The US and UK also proved lucrative foreign markets. Mato Grosso beef worth over $66 million went to the US, and over $15 millions’ worth went to the UK.

With a cattle industry well-known to be driving deforestation in Brazil, and world buyers embroiled in this tainted trade, it is no coincidence that Mato Grosso also has Brazil’s second highest level of tree cover loss according to the most recent Global Forest Watch data.

What we did

Global Witness developed a methodology for analysing data on deforestation, cattle movements and land boundaries to calculate the deforestation linked to cattle in Brazilian supply chains.

In this new investigation, we applied the same methodology to the supply chains of three of the country’s largest meat companies, JBS, Marfrig and Minerva.

In previous work, Global Witness showed that these companies bear significant responsibility for the destruction of Brazilian forests.

Our 2020 report, Beef, Banks and the Brazilian Amazon, used similar public data to expose how the meatpackers were failing to remove vast swathes of deforested Amazon land in Brazil’s Pará state from their supply chains. Local prosecutors would later confirm our findings.

In Mato Grosso, Global Witness traced movements of cattle to the three meatpackers’ slaughterhouses using animal transport permits known as GTAs.

These contain essential information that allows for public scrutiny of the beef companies’ supply chains – including the cattle’s origin, and the names of their buyer and seller.

Using public information from the Sanitary Agency of the State of Mato Grosso (INDEA), we found out which cattle ranches provided animals to JBS, Marfrig and Minerva’s slaughterhouses.

Significant traffic of cattle occurred between January 2018 and July 2019, the time frame for which GTA records were available.

We then used a state database of ranches and deforestation information from Brazil’s space research agency, both publicly available, to analyse whether there was evidence of trees being cut down on the ranches.

Next, Global Witness used official records on deforestation permits to see whether the deforestation recorded in these ranches was legal or not.

This permit (called Autorização de Desmate in Mato Grosso and Autorização de Supressão de Vegetação in Pará) is legally required for deforestation in any biome, whether on public and private land.

The body authorised to issue such permits in Mato Grosso is the state’s environmental secretariat, SEMA.

Using SEMA’s online database, including its information on whether these ranches had an environmental recovery plan, Global Witness has for the first time applied our methodology in Pará to a large new dataset – in Mato Grosso state, Brazil’s cattle capital.

Our findings reveal the seriousness of deforestation for ranching in the state’s Cerrado area. The biome was not covered in Public Prosecutors’ recently published first audits of the beef giants’ operations in the state, which dealt only with the meatpackers’ operations in the Amazon.

The results show a state-level audit system is urgently needed in all of Brazil’s forested states, for both the Cerrado and Amazon.

What we found

The following charts compare deforestation in the supply chains of the three big beef companies within Mato Grosso’s Amazon and Cerrado regions.

A Global Witness analysis of deforestation in ranches supplying cattle to the big three meatpackers shows that almost all clearances were unauthorised. That is, deforestation was undertaken without a legally required permit.

JBS, Marfrig, and Minerva, all major exporters to the EU, may not be able export without such permits for much longer.

The EU Deforestation-free products Regulation (EUDR) will soon prohibit the import of products such as beef and leather that are produced on illegally deforested land in the Cerrado, because they do not comply with Brazilian law (see box "The EUDR and the Cerrado").

Similar legislation in the UK, the Environment Act 2021, introduced provisions to restrict forest risk commodities that are produced illegally under the producer country’s laws.

The British government’s 2023 Environmental Improvement Plan states these provisions will be implemented through secondary legislation “at the earliest opportunity”.

The EUDR and the Cerrado

The EU Deforestation-free products Regulation (EUDR) aims to minimise the EU’s contribution to deforestation and forest degradation worldwide.

The regulation, which “enters into application” on 30 December 2024 (or 30 June 2025 for small businesses), requires operators and traders who want to trade agricultural products in the EU market to prove that they are both "deforestation-free" (produced on land that was not subject to deforestation after 31 December 2020) and legal (compliant with all relevant applicable laws in force in the country of production).

The EUDR currently covers products related to the clearing of forest ecosystems by using the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) definition of forest. This means that large areas of the Cerrado are currently excluded from the EUDR definition of "forest" and "deforestation-free".

However, the EUDR also requires companies to comply with legislation in the country of production, including local environmental laws and forest-related rules, regardless of the 31 December 2020 cut-off date.

This could mean illegalities in the clearance of land for cattle ranching in the Cerrado puts products such as beef and leather at high risk of being prevented from entering the EU market once the EUDR enters into application.

Our investigation found one in three cows from the Cerrado region in Mato Grosso were connected to illegal deforestation.

The first of the upcoming reviews of the EUDR will assess whether to expand its scope beyond forest to "other wooded land", and Global Witness will be pushing for the integration of the Cerrado biome fully in the law.

If we’re successful, companies could be restricted from putting products on the EU market that are linked to Cerrado deforestation, regardless of whether the deforestation was legal or not under Brazilian law.

There is significant demand for Brazilian beef in both domestic and export markets. In 2020, Brazil exported nearly twice as much beef from the Cerrado as it did from the Amazon.

Now Global Witness research shows that the deforestation footprint of beef from the Cerrado dwarfs that of the Amazon.

In fact, each cow the beef giants purchased from Mato Grosso can be linked to an average 1,132 m2 (0.11 hectares) of deforestation in the Cerrado, compared to an average 85 m2 (0.01 hectares) in the Amazon.

Global Witness’ analysis of Brazilian customs data found significant export of refrigerated and frozen beef from Mato Grosso state to the UK.

In 2018 and 2019, the years for which GTAs were analysed in this report, exports of these products to the UK were 1,269 tonnes and 1,690 tonnes, respectively.

In the years after, as deforestation in the Cerrado continued to rise, exports to the UK remained relatively stable, hitting 1,771 tonnes in 2023.

Further analysis using commercially available trade data revealed the mass of beef exported to the UK from Mato Grosso by the three companies analysed in this report.

From 2018 to 2023, the UK imported 2,223 tonnes from JBS, 1,743 tonnes from Marfrig and 683 tonnes from Minerva.

Combined, that suggests that these three companies were responsible for almost half of all the beef sent to the UK from Mato Grosso state during this six year period.

Analysis of certification data obtained through Freedom of Information laws in Brazil also revealed that during the 2018 and 2019, the years for which GTAs were analysed in this report, EU countries were able to import beef from 14 slaughterhouses in Mato Grosso state – seven owned by JBS, four by Minerva and three by Marfrig.

When the EUDR is fully in force, such imports to the EU should be illegal due to the lack of the required permits proving the legality of the associated forest clearances.

In response to our findings, JBS refuted our analysis and said that Global Witness used different criteria from that of Brazil’s federal prosecutors who monitor their activity “resulting in misleading conclusions.”

The company said that only 482 out of the 611 farms analysed by Global Witness were on the companies’ supplier database, and that all cattle purchases from these farms were legally compliant between 2008 and 2019.

Of these farms, however, 88 farms have since been restricted from selling to the company due to non-compliance even before Global Witness contacted the company about the findings of this report.

The remaining 394 farms are still legally compliant, it said.

Marfrig refuted Global Witness’ findings on a number of technical grounds, including questioning the deforestation database which Global Witness used, and said that insufficient information was provided by Global Witness for the company to cross-reference all of our findings.

It said that its own internal monitoring systems are in line with federal Brazilian law and that its cattle purchasing operations are audited by a third party.

In 2023, for the 11th consecutive year, it said this resulted in the company achieving 100% compliance with Brazilian law.

In a statement the company said: “We emphasize that Marfrig is strongly committed to conciliate its operations with sustainability, especially the conservation of Brazilian biomes, constantly developing and applying technologies to mitigate risks, permanently engaging suppliers and ensuring transparency for all stakeholders.”

In both JBS’ and Marfrig’s communication with Global Witness, the companies suggested that we have used different criteria than public prosecutors in Brazil who monitor the companies’ deforestation activity.

Global Witness accepts that we used a slightly more stringent process in our methodology for identifying small cases of deforestation within cattle farms than that of the public prosecutor, but believes the difference this made to our overall findings is minimal.

This is the only small difference in our approach to that of the public prosecutor, and we believe it makes our work more robust.

In a statement, Minerva did not directly address Global Witness’s findings but sent details of its environmental and traceability commitments.

The company said its monitoring of direct suppliers “guarantees” its production chain “is free of illegal deforestation, labour practices similar to slavery or child labour, overlaps with protected areas, or environmental embargoes.” No evidence was presented to dispute our research.

Minerva also said it blocks suppliers found to violate its policies and commitments.

The evidence that Global Witness has identified is one of a failure of diligence around supply chains.

Global Witness does not suggest that JBS, Marfrig or Minerva have authorised or commissioned the deforestation of any land from any of the farms or ranches that supply animals to them.

However, the companies are in a position to influence change of practice on the ground, and to curb illegal deforestation.

Deforested area in Alta Floresta, Mato Grosso state, July 2020. Christian Braga / Greenpeace

Commitment issues

Stopping deforestation is a challenge for Brazilian authorities. In the Cerrado, there is little protection compared to that provided by zero-deforestation agreements in the Amazon which many meatpackers have committed to.

This discrepancy has implications for the planet’s climate. A 2018 study showed two major supply chain agreements that had dramatically reduced deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon resulted in "spillover" effects of increased deforestation and native plant loss in the neighbouring Cerrado savannah.

JBS, Marfrig and Minerva are signatories to one of these agreements, the legally binding Terms of Adjustment of Conduct (TAC) covering beef, which bans sales from properties with illegal deforestation.

The first such deal was created by state prosecutors in Pará in 2009, then extended to the rest of the Amazon.

The beef giants have also signed the G4 Cattle Agreement with Greenpeace.

The voluntary policies, created after pressure from the environmental group, block them from buying animals from farms within the Amazon with any kind of deforestation, even if it was legal, and commit them to set up systems to monitor deforestation risk in their supplies.

In addition, Marfrig and JBS signed legal agreements with state prosecutors in Mato Grosso in 2010 and 2013 respectively.

Our analysis suggests that these agreements are adding some protection to the Amazon when compared to the Cerrado.

By contrast, the three beef firms have only made voluntary commitments concerning the world’s largest savannah.

While Minerva stated in 2021 that it has been monitoring its direct suppliers across the biome, JBS promises zero illegal deforestation in its Cerrado supply chains by 2025, and Marfrig full traceability of its Cerrado suppliers by 2030.

Previous Global Witness reports cast doubt on these non-binding promises, showing the meatpackers have repeatedly failed to live up to their word.

Investigations from Global Witness and others have repeatedly shown that monitoring is not enough. Deforestation has to stop.

The state prosecutor in Mato Grosso and their counterparts in other states must follow Pará’s lead and require legal commitments, backed up by fines for non-compliance, from the climate-wrecking cattle giants to stop deforestation across both the Amazon and the Cerrado.

Bond villains

Big banks and investment outfits such as Barclays, BNP Paribas, HSBC, ING Group, Merrill Lynch and Santander are contributing to the vast deforestation of climate-critical forests in Brazil by collectively underwriting billions of dollars’ worth of bonds in recent years for the three big beef firms driving the destruction providing working business capital.

For example, JBS in 2019 issued bonds worth $1.25 billion which were underwritten by major financial institutions including Barclays Capital.

There followed another $1 billion in bonds issued by JBS two years later, which Barclays Capital also underwrote, together with Santander Investment Securities and others.

Shares and bonds

Buying a share means an investor owns part of a company and receives a portion of its profits, as well as voting rights and influence over corporate decision making.

Underwriting a bond is different to owning shares in a company. When an investor buys a bond, it is essentially lending money to the issuer in exchange for periodic interest payments and the return of the bond’s face value when it matures.

Underwriters act as intermediaries between the bond issuer and the investor purchasing that security. The underwriter helps to set the bond’s face value, length and interest rate. They play a crucial role in helping investors determine if a business is creditworthy.

The underwriter takes responsibility for reselling the bonds on the open market, making profit in the process.

By underwriting bonds for JBS, Marfrig and Minerva, the major American, European and British financiers together facilitated greater access to finance for the meatpacking giants and, in doing so, helped market them – despite their exposure to deforestation – positively to potential investors.

Many of the global banks and financial institutions listed above as performing these duties are members of the Net Zero Banking Alliance, in which they commit to achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

Global Witness believes JBS, Marfrig and Minerva should not be receiving additional financing while they’re causing deforestation – in the Cerrado, in the Amazon, or anywhere.

Doing so fails to properly convey to would-be investors the seriousness of the environmental abuses riddling their supply chains.

Instead, by helping the Brazilian beef giants secure vital finance, the bond underwriters together provided them with a lifeline to keep fuelling land clearances in Mato Grosso and beyond.

We view the EU, US and UK financiers – whatever their pledges towards the environment – as collectively contributing to reputation laundering through their financial role that in effect promoted a product linked to deforestation.

ING told Global Witness it had toughened its policies since issuing Marfrig’s 2019 “sustainable transition” bond, to combat deforestation and promote traceability.

It said it does not currently issue bonds for the three meatpackers’ Brazilian entities or provide bond issuance or any financial services for their holding companies.

Barclays, BNP Paribas, Merrill Lynch and Santander declined to comment.

In response to our findings HSBC said it could not discuss clients due to confidentiality rules, including confirming whether a client is indeed theirs, but that the bank “does not knowingly provide financial services to high-risk customers involved directly in or sourcing from suppliers involved in deforestation … of primary tropical forest.”

Slash and earn

Drawing on information from financial data provider Refinitiv, Global Witness can disclose that as of October 2023:

- American, British and EU investment companies, namely The Vanguard Group, Capital Research Global Investors, Fidelity Management & Research Company and BlackRock, but also Dimensional Fund Advisors and Union Investment Privatfonds, among others, owned shares worth more than $885.5 million in JBS.

- American, British and EU investment companies, namely the US outfits The Vanguard Group, BlackRock and California State Teachers Retirement System (CalSTRS), owned shares worth more than $53 million in Marfrig.

- American, British and EU investment companies, namely AllianceBernstein, T. Rowe Price Associates, Compass Group, BlackRock and Lingohr & Partner Asset Management, owned shares worth nearly $211.2 million in Minerva.

Many of the financial institutions named above are members of industry-led initiatives that include commitments to reduce or eliminate their portfolios’ exposure to deforestation, like the United Nations-convened Net Zero Banking Alliance and the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative (NZAM).

This does not seem to have inhibited them from owning shares in deforesting beef companies.

Indeed rather than exit beef company ownership some like Vanguard – the world’s largest asset manager after BlackRock – have chosen to exit the NZAM green initiative in December 2022.

This mixed track record shows why regulation – rather than voluntary initiatives – in global financial centres like the EU, UK and USA is needed to require mandatory due diligence for financing of deforestation in supply chains.

Without this, banks and investor companies are failing to screen out deforestation and are contributing to the destruction of tropical rainforests.

When asked for comment, BlackRock said it holds a minority stake in all three meatpackers for its clients. The asset manager highlighted that its significant holdings in investment portfolios restrict its ability to exclude specific companies.

It reported ongoing engagement with the Brazilian firms on deforestation risks, and voting against or abstaining from their management proposals in 2023 due to governance concerns.

Union Investment Privatfonds told Global Witness it took a “critical view” of JBS and had already sold its shares in the company prior to contact by Global Witness.

Marfrig shareholder CalSTRS said it monitors its portfolio and collaborates with companies to mitigate “risks”.

AllianceBernstein declined to comment and referred questions to Minerva.

A spokesperson for Capital Group referred questions to JBS.

Dimensional Fund Advisors, Fidelity, and T. Rowe Price Associates acknowledged Global Witness’s request for comment but have yet to formally respond at the time of writing.

The remaining shareholders named above did not reply.

What we need

In light of our findings:

- Global protections are needed for the Cerrado. These must include full inclusion in the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), with a cut-off date no later than 31 December 2020.

- Financial backers of JBS, Marfrig and Minerva must use their influence to demand measurable and transparent improvements, and cease to provide lending and underwriting services until each company can demonstrate deforestation-free supply chains in Mato Grosso and beyond.

- Key financial centres – including the US, UK, EU and China – must legislate for mandatory due diligence for the financing of deforestation and strengthen financial regulations to prevent the bankrolling of companies that cause tropical deforestation.

- JBS, Marfrig and Minerva must fully implement their legal agreements covering the Amazon and end deforestation in their supply chains, publishing their supply chain audits for Mato Grosso both in the Amazon and Cerrado.

- Federal prosecutors must extend the Amazon no deforestation legal agreements, such as the harmonised protocol, to the Cerrado.

- Mato Grosso government and all state governments hosting cattle must allow public access for GTAs and implement a traceability system to allow for public scrutiny of beef company supply chains.

The Cerrado crisis: Brazil's deforestation frontline

Download ResourceRead this page in