Collagen linked to Paraguay’s deforestation crisis and encroachment on Indigenous territory has been sold by major retailers such as Amazon and Costco

Two of South America’s largest meat companies have purchased cattle from farms that have deforested large swathes of Paraguay’s last remaining climate-critical forests, Global Witness can reveal.

The new investigation found that together beef giants Minerva Foods and Frigorífico Concepción are supplied by sixteen cattle companies estimated to be responsible for over 75,000 hectares of deforestation in Paraguay’s Gran Chaco in the last three years, an area almost the size of New York City.

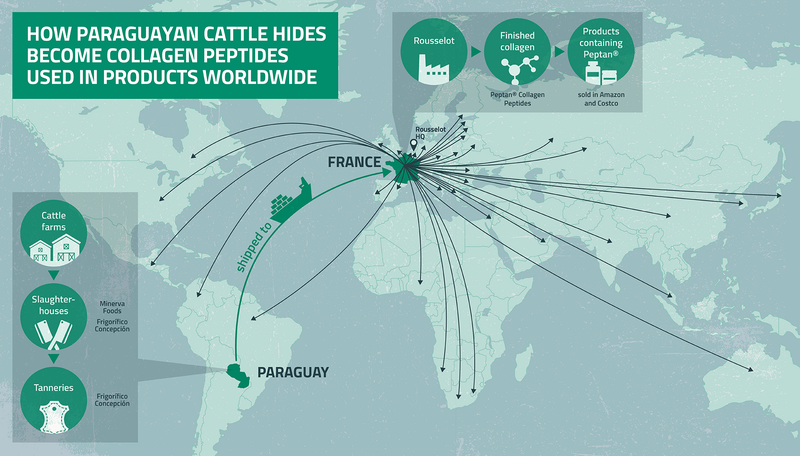

Global Witness has traced the supply chains of collagen from Paraguay to one of the world’s largest collagen companies, Rousselot.

Our research suggests Rousselot was supplied with over 3,000 tonnes of cattle hides sourced from Paraguay since 2022, according to trade data.

Rousselot produces collagen peptides, a key ingredient in many beauty supplements, including Peptan, which is described as the ‘world’s leading collagen brand’.

Products containing Rousselot’s collagen are sold by international retailers such as Amazon and Costco.

Weider's bovine collagen products are available in Amazon and Costco. It contains products made by Rousselot, linked to deforestation and rights abuses in Paraguay

The collagen giant also maintains active sponsorship deals with Olympic athletes and has proudly touted a partnership between one of the professional peloton’s biggest cycling teams, DSM Firmenich PostNL and a manufacturer which used Rousselot collagen peptides in its supplements.

The deforestation occurred in the Gran Chaco, a globally vital and unique ecosystem which is home to some of the last uncontacted peoples in South America outside of Brazil, the Ayoreo Totobiegosode.

A quarter of this deforestation – itself equivalent to an area larger than the city of Paris – has occurred on two farms that overlap some of the last remaining areas claimed by the Totobiegosode, threatening their way of life and cultural survival.

Cheap land, low taxes and weak environmental laws for cattle ranchers contribute to Paraguay's deforestation crisis. One farm manager Global Witness spoke to in the Chaco said that compared to Brazil, land in Paraguay was cheap and there were fewer NGOs to scrutinise what they were doing.

If current rates of deforestation in Paraguay continue, analysis by Global Witness suggests that the Chaco would cease to exist by 2080 – with devastating results for Paraguay’s Indigenous communities and the climate.

Paraguay’s disappearing forest

This is the Chaco of northern Paraguay.

Over the last twenty years, the green of the forest has been disappearing. In its place, small white blocks appear everywhere – the sign of cattle farms replacing the dry forest known as the “Gran Chaco”.

“In the Chaco, the cow is queen. Having cattle signifies money and status. Everything else is secondary,” says Juan*, who works with a Paraguayan based rights organisation.

The Chaco is not as internationally famous as its northern neighbour, the Amazon. Nicknamed the “infierno verde” or “green hell” for its unforgiving climate and conditions, its deforestation rate has ranked among the highest in the world in recent years.

We produce food for people all over the world, but at what cost? At the cost of nature

“The only lung [of forest] that will remain in a few years will be Defensores del Chaco,” said Silvino Gonzalez, who manages the national park of the same name.

He later added: “We produce food for people all over the world, but at what cost? At the cost of nature.”

The departments that make up the Northern or “Dry Chaco” – Presidente Hayes, Boquerón and Alto Paraguay – have lost 30% of their tree cover over the last twenty years, totalling 5.42 million hectares of forest.

This is over twice the size of Wales or just under half the size of the state of Pennsylvania.

The forest is also home to some of the last remaining voluntarily isolated Indigenous Peoples in the Americas outside of Brazil. Despite this, stories about Paraguay and its forests rarely receive international attention.

What causes high levels of deforestation in Paraguay?

At the time of writing in September 2024, Asunción was covered in an orange haze from smoke emanating from fires in the north of the Chaco and the Amazon.

A number of factors drive the high levels of deforestation Global Witness saw in Paraguay.

Paraguay’s politicians firmly support the cattle industry. The current president Santiago Peña said earlier this year: “I have no doubt that Paraguay has enormous potential and that potential comes from the production capacity that exists in the countryside. Agriculture and cattle ranching, are the fundamental sectors and pillars that we have.”

Forest laws passed by the government in 1973 require landowners to maintain 25 per cent of the natural forest on their land as a “forest reserve” in most areas of the Chaco.

Pedro*, who works for an environmental organisation in Paraguay, told us that these laws - which in effect leave up to “75%” of some areas unprotected - are the key reason for Paraguay’s high deforestation rate.

He also said that the law was “antiquated” and no longer fit for purpose. Pedro said that the law had been introduced when the Chaco was still a vast forest, and now put birdlife and rare species – such as the jaguar – at risk.

Across the Chaco, numerous people Global Witness spoke to openly discussed deforestation on their farms.

At no stage did anyone involved in the cattle industry that Global Witness spoke to refer to the environmental effects of deforestation, or its effects on the country’s Indigenous peoples or biodiversity.

Sources referred to the process of clearing this richly biodiverse land for agriculture as “limpieza” or “cleaning”.

On two occasions, Global Witness met consultants within the farms who were there to carry out further deforestation on behalf of the owners.

Cheap land was cited during an interview as a reason that cattle ranchers from across the continent set up business in the country. These ranchers then obtain permission from the Ministry of Sustainable Development (MADES) to clear the forest for pasture.

One farm manager in the Chaco told Global Witness that compared to Brazil, land in Paraguay was cheap, taxes were low and there were fewer NGOs scrutinising the cattle industry.

The right to land

In 2023, Global Witness began to investigate deforestation in Paraguay and published a report on how unscrupulous cattle purchasing affected the Ayoreo Totobiegosode — an Indigenous group from the Chaco which has struggled to make its members’ voices heard on the international stage.

The Totobiegosode who have been “contacted”, often against their will, have been involved in a struggle for land and recognition for many years.

Guede*, one of the spokespeople for the group, is from Chaidi, a small settlement in the heart of Northern Chaco. It is flanked by cattle farms to the south and to the west.

Guede and his group have spent years campaigning and demanding that the state recognise a 550,000 hectare zone in the northern Chaco. The Totobiegosode officially first submitted their request for land to the state in 1993.

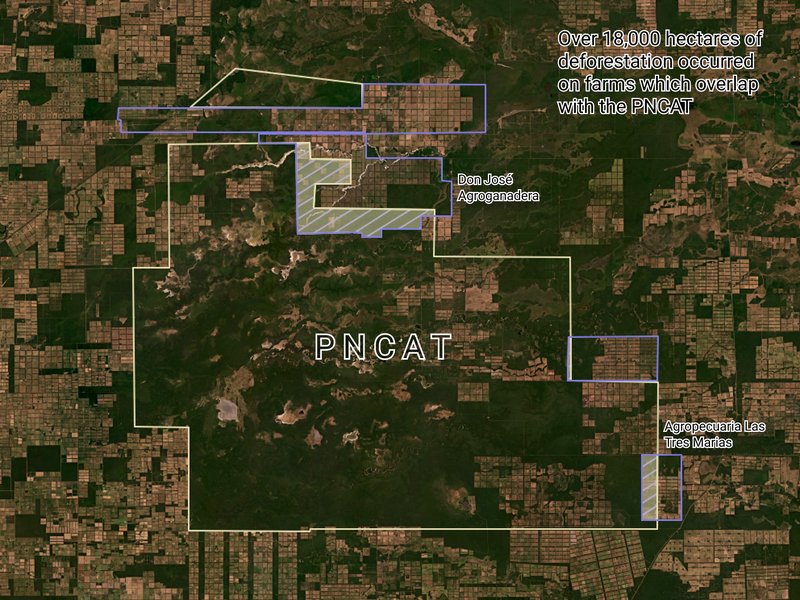

The requested area is known as the Patrimonio Nacional Y Cultural Ayoreo Totobiegosode, or by its initials, PNCAT.

The PNCAT is only a small fraction of the Totobiegosode’s traditional lands, which has been estimated at over 30 million hectares.

The Totobiegosode’s request to the Paraguayan government was submitted over thirty years ago. Despite this, and the fact that the state “recognised” the wider PNCAT area in 2001, only small sections around the villages of Chaidi and Arcojnadi are now officially titled as Totobiegosode territory.

In 2016, a regional human rights commission awarded the wider area “protective measures”. Over the next few years, Paraguay’s forest and development ministries issued contradictory rulings to a ranch within the PNCAT.

A community in the crosshairs

The definitive legal status of the 550,000 hectares area remains disputed, and this allows unscrupulous ranchers to carry out forest clearances within the indigenous territory.

Global Witness’s new research shows that two cattle companies have deforested over 18,000 hectares in farms that overlap the PNCAT between 2021-2023.

The deforested area – itself equivalent to an area larger than the city of Paris – is destroying “Eami”.

“Eami” is simultaneously the Ayoreo word for forest, territory and the group’s worldview, including “flora, fauna and all their surroundings, of which the people are part.”

The first company, Don José Agroganadera, operates a farm which overlaps within the PNCAT’s northern border. The company appears to have deforested within the PNCAT. The company is a known supplier of both Minerva Foods and Frigorífico Concepción.

Global Witness analysed NASA fire data and concluded that fires appear to have been set within Don José Agroganadera’s farms to clear forest in 2023. Starting an uncontrolled fire in forests without prior authorisation from the Environment Ministry is illegal under Paraguayan law.

In the southeast of the PNCAT, in 2022, the cattle company Agropecuaria Las Tres Marias purchased a farm now called Estancia San Julio which overlaps with the area. Since the purchase, over 1800 hectares of deforestation has occurred at the farm.

On visiting the site, Global Witness encountered contractors who stated that they were there to carry out more deforestation. Agropecuaria Las Tres Marias is a supplier to both Minerva Foods and Frigorífico Concepción.

When meat companies source cattle from companies who clear forest within indigenous areas, they legitimise forest clearance and the violation of the rights of Indigenous Peoples such as the Totobiegosode.

Such deforestation threatens Indigenous ways of life which are dependent on the forest for cultural survival.

Minerva confirmed it sourced from both Agropecuaria Las Tres Marias and Don José Agroganadera but insisted that all the farms were compliant with environmental legislation.

Frigorífico Concepción did not comment on specific suppliers, citing confidentiality. The company added that it has no information that indicates the farms overlapping those claimed by the Ayoreo Totobiegosode, but if this does exists, “it is the responsibility of the State to manage and resolve these issues.”

However, according to Columbia International law professor Daniela Ikawa: “Standards for business endorsed by the UN establish that business enterprises’ responsibility to respect human rights exists independently of States’ abilities to fulfil their own human rights obligations, and does not diminish those obligations.

"And it [the duty] exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights.”

Neither Don José Agroganadera’s representatives nor Agropecuaria Las Tres Marias’ parent company Alimar responded to a request for comment on these findings.

For us, deforestation is awful because it affects us greatly when they take the wealth from our ancestral territory. That is why we continue to fight for it

In Paraguay, Global Witness spoke with the community about deforestation.

Jonoine*, a senior figure in the community of Chaidi, said: “For us, deforestation is awful because it affects us greatly when they take the wealth from our ancestral territory. That is why we continue to fight for it.”

It is not only the PNCAT and the Ayoreo Totobiegosode that are under threat. The wider Chaco continues to face significant environmental pressure from cattle ranching.

Deforestation giants

Deforestation methodology

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), deforestation is defined as “the conversion of forested areas to non-forest land use such as arable land, urban use, logged area or wasteland. Deforestation is the conversion of forest to another land use or the long-term reduction of tree canopy cover below the 10% threshold.”

In this report, Global Witness uses the FAO’s definition of deforestation, whereby numerical figures for deforestation were calculated using satellite imagery. Global Witness acknowledges, however, that using satellite imagery is not infallible and that resulting calculations contain small but unavoidable margins of error.

The figures are inferences based on satellite imagery, rather than built on extensive evidence of every hectare of deforestation on the ground. Ultimately, this means where Global Witness identifies deforestation, Global Witness assesses that there is a high degree of likelihood of deforestation in that area, rather than deforestation being a certainty.

For this report’s analysis, Global Witness identified both the boundaries of the cattle farms and their deforestation via a range of sources. These included satellite data, Paraguay government data, Paraguay land registry information, local sources in Paraguay and online tools including Google Maps.

For a detailed explanation of Global Witness’ deforestation analysis in this report, please download this investigation's methodology document.

In total, Global Witness’ new analysis of deforestation in Paraguay uncovered almost 75,000 hectares of forest clearance across the Gran Chaco linked to both Minerva and Frigorífico Concepción between 2021 and 2023.

Map of supplier farms selling to Minerva Foods and Frigorífico Concepción, 2021-2023

Source: Global Witness. Data from Catastro Paraguayo, Global Forest Watch, Federación por la Autodeterminación de los Pueblos Indígenas.

Map: Leaflet, Planet Labs.

The total amount of deforestation has occurred on farms owned by 16 cattle companies that supply the meat giants.

This is an area almost the size of New York City.

The issue of deforestation is compounded by the fact that neither Minerva Foods or Frigorífico Concepción has a comprehensive “zero deforestation” policy applicable for their Paraguayan operations that aims to remove all forest loss, whether legal or illegal, from their supply chain.

Both meatpackers claim to use state of the art satellite monitoring technology to ensure the compliance of their suppliers with their sustainability policies.

However, in the absence of a zero-deforestation policy, this technology appears unable to prevent the incidences of deforestation in their supply chain identified by Global Witness.

These new findings are at odds with how the two meat companies frequently promote their sustainable approach to business.

Minerva, for example, has a target to be net zero by 2035. The company also claims to “contribute to the conservation of the planet, to the prosperity of people, and the well being of animals.”

When responding to the allegations made in this report, Minerva stated that the company “carries out all its operations in Paraguay in compliance with current environmental legislation.”

The company said it carries out satellite monitoring of its supplier farms, adding it blocked 243 ranchers in Paraguay in 2022, especially for their roles in “illegal deforestation and the invasion of indigenous lands.”

Minerva also confirmed that the company sourced cattle from farms owned by thirteen of the sixteen companies cited in this report.

Frigorífico Concepción has a zero-deforestation policy for their Brazilian subsidiary, but not for Paraguay.

When replying to the allegations made by Global Witness, the company stated that it had a firm commitment in Paraguay to “not purchase cattle which comes from areas affected by illegal deforestation.”

The company cited confidentiality regarding their Paraguayan supply chain. Whilst the company did not confirm the link, it did not deny that it was linked to all 16 cattle companies and the total amount of deforestation.

Global Witness has assessed that Frigorífico Concepción sources from at least eleven of the cattle companies in this report, responsible for over 57,000 hectares of clearance in the same time period.

Based on information provided by sources we spoke to on the ground, Global Witness assesses that Frigorífico Concepción is likely linked to all sixteen suppliers.

The company state on their website that it “promotes a model of continuous improvement and recognize that protecting the environment and conserving resources provides value and security for current and future generations.”

Cattle production for beef and leather is the biggest agricultural driver of deforestation globally: failure to effectively tackle these supply chains risks catastrophic consequences

UK NGO Global Canopy runs the Forest 500, one of the most well-known international assessments of deforestation and sustainability commitments made by companies and financial institutions in global commodity sectors.

Emma Thompson, who leads the programme, said, “Cattle production for beef and leather is the biggest agricultural driver of deforestation globally: failure to effectively tackle these supply chains risks catastrophic consequences.

"We need to see multinational corporations publish comprehensive zero deforestation and conversion commitments across all biomes where they operate or source, as well as evidence of how they are implementing these commitments.

"Lax government policies cannot be an excuse for inaction.”

Agroganadera Concepción

Global Witness has linked Frigorífico Concepción to significant deforestation in the Chaco since 2021.

Although the vast majority of this deforestation occurs in the company’s supply chain, a proportion of this deforestation occurs on a farm owned directly by the company.

Global Witness’ analysis shows that Agroganadera Concepción has cleared over 2,000 hectares of forest in Northern Chaco. The company operates a cattle farm based in the district of Fuerte Olimpo in northern Paraguay.

Public communications from Frigorífico Concepción show that Agroganadera Concepción was established as a fully owned subsidiary of Frigorífico Concepción to ensure a steady supply of cattle to the slaughterhouses of the parent company.

An analysis of fire alerts also shows an apparent use of fire to clear the forest for pasture in September 2023. The satellite imagery below evidences the extent of the fire within the Agroganadera Concepción farm boundaries.

The company told Global Witness that fires spontaneously occur during the dry season and effects the entire region, not just Agroganadera Concepción.

This is not the first time the company and its CEO, Jair Antonio de Lima have faced legal and reputational issues in Paraguay.

In 2019, Frigorífico Concepción was reportedly fined by the Paraguayan government for smuggling beef into the country illegally. De Lima was also reportedly named as a defendant in a complaint brought before the US Department of Justice money laundering case in 2022.

Frigorífico Concepción accepted it had received a fine from the Animal Health ministry but stated the final amount was only USD $12,000.

Regarding the US Department of Justice complaint, the company said it “had not been notified of any complaint submitted” and rejected the allegations categorically.

Collagen: Wellness, tainted

Rousselot is one of the world’s largest collagen companies. Headquartered in the Netherlands, and with its main production site based in Angouleme, France, the company is far removed from the devastation in the Gran Chaco.

The company is a subsidiary of US health major Darling Ingredients. Darling Ingredients is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Darling is a key player in a collagen industry that has grown significantly over the last decade. The craze has burgeoned to a $4 billion industry globally, with celebrities lauding its benefits for the skin and youthful longevity.

Rousselot advertises its products as improving sports performance, as well as joint and bone health.

Rousselot also claims: “We make sure we fully understand the supply chains we use and have implemented tracing systems to follow our raw materials.”

Collagen manufacturers, including Rousselot, frequently claim that bovine collagen comes from “grass fed” cows or is a “natural product”, but do not typically give information on where the collagen has come from.

However, through an analysis of trade data, Global Witness has been able to see a lesser-known part of the wellness craze.

An analysis of trade date shows 3000 tonnes of cattle hides has been shipped from Frigorífico Concepción’s tanneries to Rousselot’s factories in France, marked “for the production of collagen”.

Whilst an analysis of trade data did not show that Minerva supplies Rousselot, a 2023 report showed a link between the two companies in Brazil.

When Global Witness questioned Rousselot on their relationship with Minerva Foods, Darling Ingredients stated that: “We stand by our commitment to sourcing raw materials responsibly and sustainably”.

Collagen sold by major stores

Rousselot then turns the hides it purchases into collagen peptides.

Bovine collagen is one of the ingredients in Rousselot brand Peptan, which is described as the ‘world’s leading collagen brand’ and which is now found all over the globe.

Global Witness found that products containing collagen from Rousselot are sold by global stores like Amazon and Costco.

Amazon’s UK store appears to sell at least three separate brands of collagen that contain branded Peptan bovine collagen, including by well-known supplements manufacturer Weider.

It is highly likely Rousselot’s collagen appears in many other products sold in stores, as Rousselot state that Peptan is usually labelled as “collagen peptides” or “hydrolyzed collagen”. A search for collagen peptides on Amazon returns almost 1000 different products.

Amazon did not respond to the request for comment. Costco said it was reviewing the issue but did not provide further comment.

Weider, mentioned above, declined to comment.

Nutravita’s Peptan collagen was sold by Superdrug. The company stated that Peptan was last used in the referred product in 2022 and it was no longer using Peptan.

When reviewing Global Witness’s request, it said it discovered "outdated information" online and Nutravita’s bovine peptan collagen product listing is now no longer available on Superdrug’s website.

Superdrug said: “We are investigating these claims with Nutravita and will take appropriate action once this investigation is complete. We can confirm that no products manufactured directly for Superdrug contain bovine collagen products produced by Rousselot.”

Sporting successes

Rousselot also maintains active sponsorship deals with Olympic athletes and claimed in 2023 that the cyclists of one of the pro peloton’s biggest cycling teams, DSM Firmenich postNL, took Sanas promoted Peptan collagen “shots” called Cartiplus “every day”.

In the tough world of professional cycling, the Dutch team may have owed a small proportion of its success in recent years to products linked to the destruction of Indigenous territories in Paraguay.

Sanas said that it was not the manufacturer of Cartiplus and stated that their partnership with DSM Firmenich had ended, but declined to provide further information. It stated it was unaware of the issues in Rousselot’s supply chain.

DSM Firmenich PostNL stated that it had terminated their partnership with Sanas in 2023 but declined to comment further.

Global Witness does not suggest that DSM Firmenich post NL or Rousselot’s ambassadors were previously aware of the supply chain issues discussed in this report.

The way forward

Not one of the meatpackers or Darling Ingredients suggested that they would change their sourcing patterns as a result of Global Witness’ findings.

Global Witness asked Minerva and Frigorífico Concepción to confirm that it would continue to source cattle from Agroganadera Don Jose and Agropecuaria Las Tres Marias.

Minerva said that its policy “follows the principles of environmental legislation in force in each country where it operates and the property's compliance is checked for each new purchase.”

Frigorífico Concepción stated that “the company will continue to buy cattle from suppliers who comply with all legal marketing requirements and who are in a legal standing with the corresponding public institutions.”

Global Witness asked Darling Ingredients whether Rousselot would continue to source from companies connected to Paraguay’s deforestation crisis. The company did not respond to these questions.

Only one Paraguayan cattle company replied to Global Witness’ request for comment. Seagro SA stated that all of their operations followed Paraguayan environmental law.

Global Witness contacted each meatpacker, cosmetics group, store and cattle company mentioned in this report for comment. To read their responses, please download this investigation's additional comments.

Back in Paraguay, Global Witness asked Guede about the future he wanted for the Ayoreo Totobiegosode:

“Meat companies must stop buying from producers that occupy indigenous territories. Many of these farms don’t benefit anyone except the owner [of the land] and a few others. And it just creates more need for people in our territory, who are poor.

“If the Ayoreo ceased to exist, Paraguay would lose a part of its fundamental spirit. If our territory were lost, the country would also lose a huge conservation asset. The greatest conservation assets Paraguay have nationally are within indigenous territories.

“I think that the authorities must act now for the future.”

* These names have been changed at the request of the interviewee.

-

Opportunities to comment – The price of beauty: Popular collagen brands drive deforestation and rights abuses in Paraguay 1.9MB (pdf format)

-

Methodology – The price of beauty: Popular collagen brands drive deforestation and rights abuses in Paraguay 285.2KB (pdf format)

-

Recommendations for policymakers – The price of beauty: Popular collagen brands drive deforestation and rights abuses in Paraguay 291.9KB (pdf format)

Read this page in