Summary

As the United Nation’s COP26 climate talks in Glasgow came to an end last November, the governments of 141 countries containing more than 3.6 billion hectares of forests added their names to a statement pledging to end and reverse deforestation by 2030

They all recognised the importance of forests in the global effort to limit temperature rises to 1.5°C, including Brazil – despite spiralling deforestation under President Bolsonaro.

Yet one statistic was conspicuous for its absence at the conference: last year’s deforestation rate in the Brazilian Amazon.

Anonymous cabinet ministers working for Bolsonaro reportedly told the Associated Press the government withheld this information to avoid hampering their negotiations.

When the figure was later released, it showed the worst rate of Amazon clearance since 2006, almost equivalent to the size of the sprawling metropolitan area of Tokyo, with experts blaming this on the President’s dismantling of environmental safeguards.

The Brazilian Amazon has been devastated by demand for cattle. Lalo de Almeida / Panos / Folhapress

Cattle ranching is at the centre of this destruction. Analyses have shown that beef is the leading driver of tropical deforestation, accounting for an area of land the size of Sweden – four times greater than palm oil, the second-most destructive commodity.

In Brazil, research has shown 70% of the felled Amazon is now populated by cattle, with Brazilian meat company JBS – reportedly the world's largest – the top buyer.

The beef giant was also at COP26, signing high level no deforestation commitments and claiming it has zero tolerance for it.

It did not mention that, weeks earlier, an audit of its supply chain by Brazilian prosecutors in one Amazon state had caught it buying over one-third of its cattle from ranches responsible for illegal deforestation.

This corroborated the findings of a previous Global Witness report which exposed how JBS had bought cattle from 327 ranches containing tens of thousands of football fields worth of illegal deforestation, contrary to its legal no deforestation obligations with the prosecutors.

This investigation now finds that in the wake of the above international pledges, JBS continued buying from 144 of the same ranches in the Amazon state of Pará that were exposed in our previous report, once again failing to comply with its legal agreements with the prosecutors (JBS denied these claims).

It also failed to monitor an additional 470 ranches further up its supply chain, containing an estimated 40,000 football pitches of illegal Amazon clearance – also contrary to its obligations.

In response, JBS said it had set up a new system that was monitoring these suppliers and had established 15 sustainability offices across Brazil to help ranchers comply with environmental law.

Cash Cow

JBS is reportedly one of the largest food companies on Earth. Luke Sharrett / Bloomberg via Getty Images

JBS and the Seronni cattle dynasty

We can also reveal that one of JBS’s regular Pará suppliers, the wealthy Seronni cattle dynasty, presided over a decade-long saga of alleged human rights abuses, the use of slave labour, illegal deforestation, land grabs and cattle laundering – exemplifying how the beef giant contributes to many of the ills that currently plague the Amazon.

When the allegations of slave labour were put to JBS last year it claimed to have blocked the ranchers. Yet we found it continued buying cattle from their farms through third parties, even after our warnings, repeatedly failing to implement its legal obligations.

In response, JBS said the ranchers acted in bad faith and had deliberately circumvented its monitoring system.

The company also said that it blocked the third parties as soon as it evaluated our information.

The Seronnis failed to reply despite multiple offers for comment.

That such ranchers should persistently get around JBS’s due diligence efforts – its products then sold across the world – is a sad indictment of the global cattle market.

Questionable origins

Yet not only Brazil’s government and beef companies are complicit in this destruction. Also implicated are one of the world’s most prestigious leather manufacturers, Italian company Gruppo Mastrotto.

It imported leather from JBS’s problematic Pará slaughterhouses found by us and Brazilian prosecutors to have purchased hundreds of thousands of cattle from ranches containing illegal Amazon deforestation.

The firm also has subsidiaries that source leather in Brazil, but was rated as having a 0% traceability record for the ranch of origin of its products, meaning it has no idea whether its leather is linked to deforestation.

Despite this, it services car companies like Volkswagen, owner of Audi, Porsche, Bentley, Lamborghini, as well as Toyota and the furniture maker IKEA.

JBS also exported leather from its problematic Pará operations to a company it owns in Italy, Conceria Priante, in spite of its widespread lack of compliance with its legal no deforestation obligations.

European consumers thus risk purchasing products linked to the egregious wrongs mentioned above.

Mastrotto said it no longer buys from JBS, though it did not respond when questioned on whether it could identify the ranch of origin of the leather its Brazilian subsidiaries buy.

Volkswagen and Toyota, meanwhile, both said their policies ensure the leather they buy is not linked to environmental crime, but failed to respond on whether they found it acceptable one of their suppliers had been found wanting on tracing its leather.

IKEA stated none of its Mastrotto leather came from JBS and that it requires its suppliers to identify the ranch of origin of its products.

Aerial images of cattle fields in São Félix do Xingu, Pará State, Brazil, 2019. Fábio Nascimento / Greenpeace

Supermarket suppliers

Our new investigation also shows how British supermarkets like Morrisons, Sainsbury’s, Iceland and Asda in February 2022 stocked JBS corned beef sourced from Brazil by a UK supplier, even as some of them publicly rejected buying directly from the company and as they all condemned President Bolsonaro’s weakening of forest protections.

Morrisons told us it would drop the JBS product found in its stores.

Sainsbury’s and Iceland both claimed they engage with suppliers to ensure they source their beef responsibly, while Asda simply failed to reply despite multiple requests for comment.

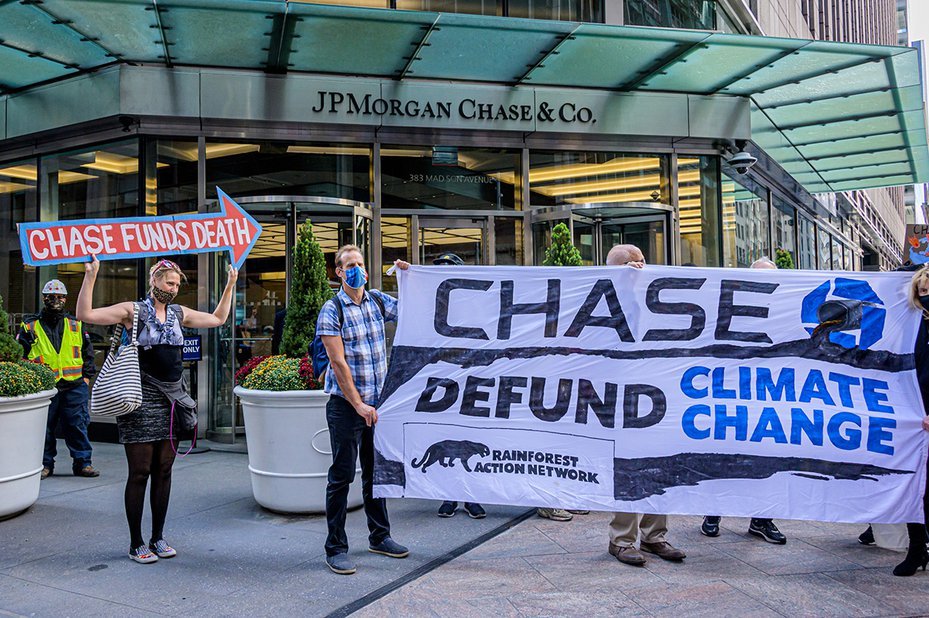

Moreover, global banks and asset managers such as Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Barclays, JPMorgan, Santander and BlackRock have for years funnelled billions of dollars to JBS and continue to do so – while at the same time pledging to remove deforestation from their portfolios.

When asked if the findings in this report affected their ongoing exposure to JBS, some variously claimed they were either engaging with the company to improve its performance or requiring it remove deforestation from its supply chains faster.

Others declined to comment or did not reply despite numerous requests.

A customer shops for meat at a British supermarket. Tolga Akmen / AFP via Getty Images

All these financial actors are encouraged by the credit checking agencies S&P, Moody’s and Fitch, that repeatedly give the beef giant favourable ratings, notwithstanding its links to Amazon destruction.

In response, all three replied saying they only analyse whether JBS’s environmental performance impacts its ability to repay its debts.

The global financial sector is thus the fuel that powers harmful agribusiness. Regulating it is arguably the best chance to reduce its contribution to deforestation, given the well reported failures of their voluntary no deforestation initiatives.

Yet as governments in the UK, the EU and the US plan laws to ensure their companies do not import commodities linked to deforestation, they are currently leaving out the financial sector. At the same time, the UK is also considering only phasing in certain products linked to deforestation for its commodity legislation.

This means beef and leather imports linked to forest clearance might be unregulated until at least 2027.

These delays risk undermining the new laws. We call for governments to ensure they are rapid and effective in tackling all the key agricultural commodities associated with deforestation, including cattle and its derived products, and introducing similar requirements for financial institutions.

Only then can unwitting consumers and bank account holders know their supermarkets and banks are doing all they can to prevent deforestation linked to companies like JBS and ranchers like the Seronnis.

Introduction

Amazon deforestation has been at its highest since 2006. Global Witness

The labourers were obliged to drink, bathe and clean their utensils using dirty water from stagnant pools filled with cow manure. At night they were forced to sleep with farmyard animals, with no running water or electricity.

They were required to work for 17 hours a day, and not provided with toilets or clothing. They were given no protection against toxic chemicals used in the farm, nor any protective equipment when operating heavy machinery.

Wages went unpaid and they were told they had unspecified debts to settle. When they complained, they were shot at and chased out of the ranch, all their belongings burnt. In short, they were treated as slave labourers.

Those were the conclusions made by Brazil’s Ministry of Work during inspections carried out in 2006, 2018 and 2021 on two large ranches in the Amazon state of Pará belonging to Sergio Xavier Luis Seronni and his son, Sergio Seronni.

We have unearthed evidence of how these ranchers destroyed vast swathes of Amazon forest, involving land-grabbing and cattle laundering, while repeatedly sending cattle to JBS, the world’s biggest beef company.

The beef giant then exported leather from its Pará slaughterhouses to top-end Italian leather manufacturer Grupo Mastrotto, we have learned.

This company supplies Volkswagen Group, owner of Audi, Porsche, Bentley, Lamborghini, Seat and Skoda. Toyota and IKEA were also among the clients.

Some of Europe’s biggest and most prestigious brands and their customers buy leather from an Italian company linked to Amazon deforestation and serious human rights abuses.

Destroying the Amazon

JBS’s contribution to Amazon deforestation is well established. In 2020, our report Beef, Banks and the Brazilian Amazon revealed that between 2017 and 2019, JBS bought cattle from 327 ranches in Pará containing over 20,000 football fields-worth of illegal deforestation.

This was contrary to its no deforestation legal agreements with Federal prosecutors and voluntary pledges – though it denied the allegations.

We also exposed how JBS failed to monitor an additional 3,270 Amazon ranches further up its supply chain between 2016 and 2019, containing 98,000ha of deforestation in Pará.

As of September 2020, the company claimed it would extend its monitoring to such suppliers.

Repeating the analysis, we have now found that in 2020, JBS directly purchased from 144 of the same ranches, failing once again to fully comply with its legal obligations and despite its previous protestations of innocence.

We can also disclose that for the same year, 470 of its so-called "indirect suppliers" – who rear cattle sold on to fattening ranches then traded on to JBS – contained an estimated 34,000ha of illegal Amazon deforestation in their ranches.

Most deforestation in JBS’s supply chain is found in the suppliers of its suppliers. Marizilda Cruppe / EVE / Greenpeace

In total, around 1,600 indirect suppliers in Pará contained 48,000ha of deforestation on their ranches, legal or otherwise.

JBS’s legally-binding zero deforestation obligations required it to start monitoring these farms as far back as 2011.

The company announced in late 2020 it would only fully monitor them by 2025, failing to meet commitments it made over a decade before.

These delayed commitments come at a time when Amazon deforestation reaches record highs under the Bolsonaro government’s dismantling of environmental protections.

Yet the beef giant continues to be financed and serviced by Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Barclays, Santander, JP Morgan and BlackRock to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars, in spite of its ongoing connection to deforestation, land-grabbing and human rights abuses.

Last year, for example, Barclays facilitated a bond deal for JBS worth almost $1 billion.

The bank has continually done business with it over multiple years despite our numerous reports on the company.

Tipping point

JBS’s failure to block ranchers such as the Seronnis, and its continued backing by major UK, EU and US-based financiers and importers, shows that more rigorous due diligence on deforestation risk is required.

It underlines the urgent need for governments to implement legislation to prohibit the use and funding of beef and leather fuelling deforestation.

Scientists are warning the Amazon could reach a tipping point and become dry savannah if this destruction continues.

Allowing banks and investment funds to carry on servicing or financing harmful agribusiness weakens the potential impact the new legislation could have on conserving this crucial ecosystem and the people who live in and rely on it.

We will now focus in on the particularly egregious case of the Seronni ranches and their use of slave labour, as well as their destruction of vast swathes of Amazon forest, which JBS profited from.

Following the supply chain of leather from the beef giant’s slaughterhouses, the investigation will show how products from its problematic Pará slaughterhouses were exported to one of the largest leather manufacturers globally, which has commercial relationships with some of Europe’s most prestigious automobile brands and furniture sellers.

We will then take a step back to highlight the continued, systematic failings that allow JBS’s destructive business model to endure, fuelled by cheap finance from banks that talk a big game on the environment.

The Seronni ranchers

The Seronnis’ Amazon damage

Sergio Xavier Luis Seronni, kingpin of the Seronni dynasty, has a long and chequered history of illegal deforestation, human rights abuses and repeatedly treating labourers as slaves.

This affords him a lavish lifestyle. He owns both a Cessna and a Piper aeroplane and 10 companies worth almost $50 million.

Satellite imagery reveals a large house with what appears to be a pool in one of their farms, surrounded by carefully laid out trees and gardens.

Satellite image of the Serronis' Fazenda Santa Maria Boca do Monte. Maxar Technologies.

In 1999, Mr Seronni was the second-largest destroyer of Amazon forest on a list compiled by Brazil’s environmental inspection agency Ibama.

He finances the election campaigns of controversial cattle baron mayors also fined for illegal deforestation and the use of slave labour.

The Seronni family own numerous farms in the Amazon state of Pará.

Our analysis now shows two of their biggest ranches contain a combined 2,700 football fields-worth of illegal Amazon deforestation carried out between 1999 and 2018.

Brazilian government satellite data shows 552ha of forest was illegally cleared in 2008 in their Fazenda Terra Roxa ranch.

Between 2012 and 2015, another 30 football fields-worth of forest was illegally felled inside the same ranch.

In 2018, a further 1,600ha of illegal deforestation – equivalent to an area almost the size of Geneva – was discovered on another farm by Brazil’s forest inspection agency Ibama.

For this, the farm was placed on Ibama’s list of embargoed ranches.

Despite this track record, we estimate that between 2014 and 2020 the Seronnis may have made anywhere between $2 to $7 million profit from its cattle sales to the beef giant JBS.

Modern slavery

The Seronnis’ wealth was gained not only at the expense of the Amazon, but at a tragic cost to their labourers. This investigation now reveals a recurring pattern of human rights abuses and use of slave labour carried out on their properties over many years.

In 2006, in the municipality of Cumaru do Norte in southern Pará, 16 people were rescued from one of the Seronnis’ ranches, Fazenda Terra Roxa, where they were working under slave conditions. The oldest was 66.

The labourers worked 17 hour shifts with no rest, their rescuers found. They were given no shelter, no running water, were not paid and told they had unspecified debts. They cleaned their cooking gear in puddles filled with cow manure, while their makeshift slums had bin liners as walls and rooves.

Image of some of the conditions of labourers in Fazenda Terra Roxa. From FOI requests to Brazil's Ministry of Work.

The labourers were awarded compensation after an inspection carried out by Brazil’s Ministry of Work, the findings of which we have now obtained under Freedom of Information legislation.

The inspectors judged Sergio Xavier Luis Seronni and his son Sergio Seronni responsible.

In 2010 a judge ruled Seronni had illegally stolen 25 cows from a farmer. The case was settled out of court six years later.

Another incident in 2012 saw a Seronni worker found dead in one of their ranches.

A court witness statement seen by us alleged the labourer may have perished while cutting down a tree that then fell on him. He did not have protective equipment to help him do the job safely, the witness said.

The Seronnis compensated the family of the labourer to settle the case.

The abuses continued. Further Global Witness Freedom of Information requests revealed in 2018, three labourers were rescued by Brazil’s Ministry of Work from another Seronni ranch in Pará, Fazenda Santa Maria da Boca do Monte.

One worker said he was forced to sleep with the farm animals.

Another said labourers worked 15-hour shifts, were often not paid their salaries, landed with unspecified debts and handled toxic chemicals without protective equipment.

Image of the barn where one of the workers allegedly slept with farm animals, taken by Ministry of Work inspectors. From FOI requests to Brazil's Ministry of Work

Look how we live, with the water we drink filled with cow s***

They too were compensated for having endured severe privations, while the inspectors once again blamed both Sergio Xavier Luis and Sergio Seronni.

As of December 2020, the farm remained on the Ministry of Work’s list of employers involved in slave labour, but only under the name of the son.

In January 2021, the Ministry of Work carried out another inspection in the Fazenda Terra Roxa ranch, finding the use of slave labour yet again.

Investigative journalists at Reporter Brasil described how men from the Seronni ranch shot at the labourers and burnt their belongings after they complained about their treatment.

One of the workers told Reporter Brasil: “Look how we live, with the water we drink filled with cow s***. Life has been difficult … it’s so surreal.”

"A pervasive problem"

The case was taken to court by the Ministry of Work’s prosecutor, where a judge noted Brazilian law recommends the expropriation of the property in such cases.

The ranchers were fined almost $260,000 for breaching labour laws.

In an interview with Reporter Brasil, the prosecutor said: “There is the intent to resolve this impunity, and that gives me hope the Seronnis will be held accountable.”

The case is ongoing as prosecutors seek to confiscate the ranch from the family. The Seronnis deny the allegations and have launched various appeals.

Since 1995, more than 17,000 labourers have been rescued nationwide by state inspections from working in ranches under conditions of slavery, according to Reporter Brasil.

It speculates there may be many more cases, as inspections have been hit by budget cuts from the Bolsonaro government.

We can also now reveal new evidence of past and present land-grabbing by the Seronnis.

JBS again failed to remove these ranches from its supply chain, once more contrary to its voluntary and legally binding no deforestation agreements.

The land-grab

Land-grabbing in Brazil is known as “grilagem”, from the Portuguese grilo, or cricket, referring to an old practice where land-grabbers would forge land titles and leave them in drawers or boxes with crickets. The insects’ nibbling and defecation would add the patina of age to the documents.

Today, the term is commonly used to describe the illegal occupation of public land.

Ipam, a Brazilian NGO, claims land-grabbing has accounted for 2.6 million ha of Amazon deforestation – an area larger than Turkey.

Imazon, another NGO, reports that since 2017, the government’s revision of a land law has made it easier for this practice to become widespread, increasing Amazon deforestation.

So emboldened have land-grabbers become that a BBC investigation found they were openly selling illegal plots of Amazon forest on Facebook – including in Indigenous and protected areas.

Last year, we reported how a toxic competition between land-grabbers in the Indigenous area of Apyterewa in Pará had led to illegal deforestation, violence and the arrest of cattle ranchers suspected of murder.

This was likely inflamed by Bolsonaro’s rhetoric about not recognising Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

Landgrabbers operating in Apyterewa claimed to Brazilian journalists that land prices on the black market tripled in value there after his election.

JBS and rival beef company Marfrig – financed by banks such as Santander, BNP Paribas and ING – purchased cattle from ranchers linked to the dispute.

New evidence we have uncovered on the Seronni case illustrates JBS’s continued failure to monitor the problem of land-grabbing.

The Amazon state of Pará has seen some of the worst rates of deforestation in the world. Victor Moriyama / Greenpeace

Sergio Xavier Seronni lays claim to the 13,555-hectare property Fazenda Aparecida in the municipality of Santana do Araguaia, Pará.

Mr Seronni sent 7,239 cows from this property to two ranches owned by him and his son, Fazenda Boca do Monte and Fazenda Terra Roxa. These ranches in turn delivered cattle to JBS both in 2020 and in 2021.

JBS should be monitoring all three ranches to ensure their compliance with its no deforestation and land-grabbing obligations with federal prosecutors.

In Pará, all rural property owners must register their land on an electronic database called the Cadastro Ambiental Rural (CAR), which details a ranch’s proprietor, boundaries and any forest cover.

Owners face criminal or civil sanctions for any false or partial information they self-declare on the CAR.

We obtained the land titles of Sergio Xavier Seronni’s properties held by municipal land registries. These show that in 2010, a western part of the ranch Fazenda Aparecida claimed by the Seronnis on the CAR was confiscated from them after a legal case ruled it was land-grabbed.

Yet that area on the CAR database is still declared by the Seronnis as belonging to them 12 years later.

We showed this evidence to two Brazilian legal experts in land disputes, who both said it shows the Seronnis’ claim to be the owners of the property on the CAR is fraudulent.

Moreover, Brazilian law prohibits the overlap of private properties onto state forests without a license. These can only be accessed by ranchers once they have had a use defined by the state, and then only through temporary concessions. Any forest clearance is prohibited.

Yet the western extension of the property on the CAR overlaps forest that belongs to Pará, but has not yet been assigned a purpose.

Brazilian government satellite data also show 13ha of forest were illegally cleared in 2012 inside the land-grabbed area, two years after the court’s confiscation for the land-grabbing. The lawyers we consulted advised this was illegal as well.

We also spotted what appear to be cattle grazing near a water source in the land-grabbed area on satellite imagery.

What appear to be cattle grazing near a water source in an area of Fazenda Aparecida courts declared as land grabbed, which the Seronnis erroneously claim to own on the CAR. Maxar Technologies

Environmental groups have warned for years that ranchers manipulate the CAR registry to fraudulently declare ownership over properties.

They also claim new laws proposed by the Bolsonaro government – titled 510/2021 and 2.633/2020 – would legalise the actions of ranchers like the Seronnis by giving them land titles to state forests illegally occupied in this way.

The proposed acts are referred to in Brazil as the “land-grabbing bills”.

The legal and voluntary commitments JBS made in 2009 also committed it to removing land-grabbing ranchers like the Seronnis from its supply chain. Yet the last two audits published by Federal prosecutors in Pará of JBS’s compliance with this promise did not monitor such cases. Nor are there plans for any such checks to occur in future audits.

This means no one can know if JBS is fulfilling its legal agreements on this issue, nor is it being required to by the prosecutors overseeing their implementation.

But the ranchers also seemingly used trickery to "clean" cattle produced on land-grabbed and deforested land – then presenting them as legally-raised.

Cattle-laundering

The 898-hectare Fazenda Boca do Monte ranch is depicted as a square block of land on the environmental land registry of Pará – known as the Cadastro Ambiental Rural, the CAR.

Some 85% is still forested, with 120ha clear-felled in the north-west corner.

Aerial image of Fazenda Boca do Monte from Brazil’s Environmental Rural Registry. Cadastro Ambiental Rural – CAR

This ranch received cattle from the aforementioned Fazenda Aparecida, part of which was determined by the courts to have been land-grabbed. It then sold cattle directly to JBS in 2020 and 2021.

By this process, cattle from tainted properties are laundered through seemingly “clean” ones into the beef giant’s supply chain.

Yet in Fazenda Boca do Monte there are indications of cattle laundering that show the ranch is far from “clean”.

Tell-tale signs

Under guidance endorsed by Federal prosecutors in Pará and agreed to by JBS, slaughterhouses are legally prohibited from purchasing cattle from ranches where the annual production exceeds an average of three cows per hectare.

It stipulates this is currently the upper limit of animals that can feasibly be fattened on a plot of Amazon land, even with the best feed, soil and grass quality. Production rates higher than that are a certain indicator of cattle being raised elsewhere.

Yet we found that in 2020, Boca do Monte sent 1,298 cows to JBS’s slaughterhouses in Pará from just 120ha of pasture – an average of almost 11 cows per hectare.

For 2021, it received 828 cattle from the same ranch, an average of almost seven cows per hectare and more than double the permitted amount.

In addition, no cattle confinement infrastructure – identifiable by fences and rooves and used by farmers with high productivity rates to weigh cows and to provide them with extra feed – is visible in satellite imagery of the ranch.

The guidance stipulates beef companies should check whether such infrastructure exists when buying from a ranch producing more than three cows per hectare. Therefore JBS should not have purchased from the ranch according to its legal agreements.

Satellite imagery of Fazenda Boca do Monte. Maxar Technologies

Furthermore, a study of soil quality in the vicinity between 2018 and 2020 by the Brazilian University of Goias found over 14% of the pasture contained degraded soil, suggesting grass quality would be below that needed for such a high productivity rate.

Considering the total amount of cattle that left the ranch in 2020, and not only the amount sent to JBS, the productivity increases even higher to almost 14 cow heads per hectare. All this makes it inconceivable the number of declared cattle were legally fattened on this ranch.

The Seronnis have thus engaged in the use of slave labour, illegal deforestation, land-grabbing and cattle-laundering, in a pattern of civil lawbreaking and criminal behaviour spanning 20 years.

Yet JBS failed to bar the ranchers from its supply chain, repeatedly sourcing cattle from the family since at least 2014, contrary to its legal no deforestation obligations.

These allegations were put to Sergio Luiz Xavier Seronni and his son, through their lawyer, but they did not reply despite repeated requests.

Changing places

When we put the allegations of slave labour to JBS in April 2021, the company said it blocked all the Seronnis’ ranches, stating it “maintains a zero-tolerance policy where hard or forced labour is confirmed.”

The company added that it had already blocked ranches registered to Sergio Seronni, who was on the Ministry of Work’s slave labour list.

JBS said Sergio Seronni had used the tax code of his father, Sergio Luiz Xavier Seronni, and the company tax code of a firm owned by both Seronnis that was not on the slave labour list, to dodge its supplier monitoring system.

“When it became aware of this fact, JBS also blocked Sergio Luiz Xavier Seronni and his company, even though the respective [tax] numbers did not figure on the blacklist,” a spokesperson said last spring.

Cattle in the Espírito Santo livestock farm. Marizilda Cruppe / EVE / Greenpeace

Our analysis of cattle transport permits confirmed the names and tax codes of father and son Seronni were no longer used to send cows to the company after that month.

Yet then, other Seronni names began appearing more frequently on documentation of cows purchased by JBS.

Between April and August 2021, Maria Aparecida Xavier Seronni, Sirlane Honorato Seronni and Gustavo Seronni appear on the paper trail.

The trio sent a total of 426 cows to JBS from the very same father and son owned ranches involved in cattle laundering and slave labour the company claimed to have blocked, Fazendas Boca do Monte and Terra Roxa respectively.

One of the biggest beef companies on Earth once again failed to stop buying from ranches that do not comply with its legal obligations, despite being warned.

When this was put to JBS, it said the Seronnis had “been using several family members to continue to sell to JBS."

“In line with this new information, the company has blocked Sirlane Honorato Seronni, Gustavo Seronni and several other possible connections to them.

“Several CPFs [unique tax codes belonging to individuals] and farms have also been preventively blocked until we can confirm whether or not they are linked to Seronni’s family.”

The company added: “We do not condone this behaviour and have acted to preventatively block bad faith actors as soon as this new information was available.

“Unfortunately, this episode showed that even when there is a property and a producer able to supply in accordance with the terms of the protocols and policies already used by JBS and other companies in the sector, some suppliers may be deliberately circumventing JBS's socio-environmental criteria and its monitoring system.”

Its statement continued: “In order to fully investigate this and other cases, JBS will establish a Supplier Audit Committee to verify the facts and guide the company’s decision.

“During the investigation, the producer will remain preventively blocked for new purchases and will have the opportunity to present its explanations.”

Monitoring JBS's supply chain

The Seronni case study illustrates JBS’s negligence in continuing to buy cattle from 144 ranches we found contained illegal Amazon deforestation.

But these purchases are a drop in the ocean compared to the hundreds of ranches it is supposed to be monitoring further up its supply chain – the so-called indirect suppliers.

Our new analysis reveals that in Pará alone, for 2020, 470 such farms contained an estimated 40,000 football pitches of illegal Amazon clearance. Once again, this breached the company’s legal agreement with prosecutors.

Worse, 1,600 of JBS’s indirect suppliers contained an estimated 57,000 football fields of deforestation, legal or otherwise.

JBS had committed to monitoring its Amazon-based indirect suppliers as far back as 2009, but has now said it will only fully do so by 2025 – and then only for illegal deforestation.

Our analysis is also limited to just one Amazon state of the many JBS operates in.

No one knows just how many cases like those of the Seronnis are escaping its checks in other eco-systems like the Cerrado savannah, the Pantanal wetlands, the Caatinga shrublands and Brazil’s Atlantic forests.

JBS responded saying it recognised cattle purchases from 143 of the mentioned ranches.

It added that 96 of these suppliers had requested to join a program implemented by the state of Pará to ensure they start complying with Brazil’s forest laws.

The company continued to say a further 41 ranches had areas of deforestation smaller than 6.25ha and could thus be purchased from according to its commitments.

It added that in six cases the forest clearance in those ranches was found in a deforestation data set by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research it was not previously using to monitor compliance with its legal obligations.

On its indirect suppliers, the company said that in 2021 it had created a system to monitor its “suppliers’ suppliers, always respecting the confidentiality of data required by Brazilian law. Because of this, the implementation of this tool requires the engagement of producers, who need to voluntarily register their information,” JBS said.

The company stated that by 2025, its entire supply chain will be on this platform, adding that an “essential part of this strategy is the implementation of 15 Green Offices, which aim to assist producers in critical farm-level environmental actions, so they can produce while preserving the biome.

"Any supplier not registered by this time will not be able to supply to JBS.”

Despite this litany of problems, global powerhouses of both food and finance continue doing business with JBS.

The auditors

The audits: Flaws aplenty

As stated above, in December 2020, we revealed that between 2017 and 2019, JBS had bought cattle from 327 ranches that failed to comply with its no deforestation obligations (it denied these allegations).

Since then, the prosecutors have carried out an official audit of JBS’s cattle buying in Pará between 2018 and mid-2019, which was published in October last year.

This found 43.69% of the company’s audited purchases were not compliant with its legal obligations, though JBS contested 11.7% of these, arguing their purchases were justified.

It was the worst performing of the audited companies for deforestation, confirming the findings of our previous report, and at a time when Amazon deforestation is at its highest since 2006.

As a result of these failures, JBS agreed with prosecutors to pay almost $1 million to the state of Pará, to be spent on improving ranchers’ compliance with Brazil’s forest law.

The new agreement obliged JBS to adopt more stringent controls, mirroring one of our report’s recommendations.

Prosecutors also announced an investigation into JBS’s cattle purchases from one of the ranches featured in our exposé.

The prosecutors opened an investigation based on a complaint provided by an anonymous individual.

That person stated as part of the complaint that JBS “invests a lot of money in marketing, to cover up the crimes it has carried out at any cost, respecting absolutely no authority, including the Federal Prosecutor’s Office,” adding that even after having signed an agreement with the most important enforcement authority in the country, “the company continues promoting unfair competition, and worse, condones and feeds the harms caused by Amazon deforestation and stimulates the illegal commerce of animals.”

This devastating critique should be a major red flag for any company that backs JBS.

We also exposed that flawed audits of JBS’s voluntary no deforestation pledges by Norwegian auditor DNV-GL between 2016 and 2019 masked the company’s true exposure to Amazon clearance.

JBS used these audits to flaunt its supposedly green credentials to its investors and backers – though it denied the allegation.

DNV said at the time that it stopped auditing JBS and claimed restrictions in the methodologies of the audits may have accounted for the discrepancies we found.

Grant Thornton, the giant US auditor also criticised in our previous report, then took over auditing JBS for its voluntary pledges.

In August 2020, it published its results of auditing the company’s compliance with its voluntary commitment for its 2019 cattle purchases, finding that of its direct suppliers, “nothing has come to our attention that causes us to believe that the procedures adopted by the Company in the period from January 1 to December 31 were not compliant, in all material respects, with the criteria.”

This despite our December 2020 report Beef, Banks and the Brazilian Amazon finding that at least 117 ranches JBS bought cattle from in Pará in 2019 contained over 4,600 football fields of deforestation.

In response to these allegations, JBS insisted its purchases were compliant.

Beef, banks and the Brazilian Amazon

How Brazilian beef companies and their international financiers are complicit in the destruction of the Amazon

The beef company continues to rely on the use of a weak methodology for these audits.

Grant Thornton noted in the 2019 audit that it only checked “a random sample, equivalent to 10% of the total [cattle] purchases” of each of JBS’s Amazon slaughterhouses.

This means non-compliant ranches can easily slip through the net. All audits of the company’s voluntary agreement as far back as 2015 used the same sample percentage.

Grant Thornton has justified its sampling by citing auditing guidelines published by Brazil’s Federal Accounting Council (CFC), a government regulated body that oversees the implementation of accounting standards.

Yet the CFC’s auditing standards indicate the dangers of sampling, and state that they should take into account risks of “distortions not being identified, when in reality, they exist.”

In 2020, we and other NGOs exposed many cases of non-compliance which escaped the audit’s attention, likely because they were in the 90% of cases not assessed. This was widely reported by the media.

In spite of this, Grant Thornton did not increase its sample size in subsequent JBS audits.

This was followed up last year by another audit for the 2020 calendar year, this time carried out by global auditing company Control Union.

Again, the same inadequate sample was used and once more no issues were found on JBS’s compliance with its voluntary no deforestation agreement.

Asked to respond, Grant Thornton said its report “shows in great detail the limitations we experienced in gathering the information necessary to reach a conclusion about JBS S.A.’s compliance, and our report is appropriately qualified as a result of those limitations.”

Despite our questioning, the auditors did not address the issue of the inadequate sample size.

Control Union said all previous audits had used the same protocol which had been agreed on with Greenpeace, and that it does not “deviate from the contracted service.”

Pressed on whether it should have increased its auditing sample in light of various exposés of JBS’s failures on deforestation, including by Greenpeace, it did not respond.

One might think all this was enough to put off responsible banks from doing business as usual with the company.

Yet none of the above has dissuaded JBS’s financial backers.

Blackrock is one of JBS’s largest shareholders

The financiers

JBS could not operate without the backing of international finance. In 2019, we revealed UK, EU and US based-financiers funnelled almost $2.5 billion to JBS between 2013 and 2019.

This was despite civil society and the media repeatedly exposing the company’s links to deforestation.

These included Deutsche Bank, Santander, HSBC, Barclays, JP Morgan and BlackRock.

Then, in 2020, we revealed JBS had failed to prevent cattle from ranches with over 20,000 football fields worth of illegal Amazon deforestation entering its supply chains – allegations it denied.

This was while receiving hundreds of millions of dollars from some of the same financiers, despite their having voluntary no deforestation policies.

In response, BlackRock claimed it had engaged with the company to seek improved compliance with its commitments.

Barclays said it could not comment due to “confidentiality reasons,” while Santander said it had engaged with the company and if any illegality was verified it could demand its investments be repaid.

Deutsche Bank claimed its investments were on behalf of others, but failed to respond to evidence of two loans it provided to an American subsidiary of JBS worth $2.8 billion and which mature in 2022 and 2023 respectively.

We prize sustainability, and are passionate about leaving things better than we found them

Despite this series of excuses, we can disclose that between September and October of last year, investment companies controlled by Deutsche Bank, HSBC, Santander, BlackRock and JP Morgan still held shares worth over $293 million in JBS.

Meanwhile Barclays facilitated a bond sale for an American subsidiary of the beef giant in March 2021 worth almost one billion dollars.

In October 2021, we revealed how Barclays bankrolled firms across the world linked to deforestation, to the tune of $3.66 billion.

Once again, voluntary policies are consistently shown to be ineffective at affecting investor behaviour.

And for three years now, the banks and asset managers backing JBS have told us one thing whilst doing quite another.

Other lesser-known financiers of JBS appear not to have any forest policies at all aimed at dealing with their exposure to deforestation.

Vanguard Group, Fidelity Management and Dimensional Fund Advisors for example, through investment companies registered in the US and the UK, hold a combined $540 million worth of shares in the beef giant.

This track record shows why only regulation in global financial centres like the UK, the EU and the US that would require their banks and investor companies to screen out deforestation will halt their complicity in the destruction of tropical rainforests.

Asked whether our new allegations against JBS would affect its ongoing financial exposure to the company, HSBC said its asset management business held shares in the beef giant on behalf of others.

The bank said it had no influence over the decision to invest in JBS.

It added that in such cases, it engages with companies and investors to “raise any concerns” on issues like deforestation.

Banks with voluntary no deforestation policies continue to hold shares in JBS. Erik McGregor / LightRocket via Getty Images

Barclays simply repeated its answer to our previous JBS investigation, claiming it was committed to helping its “corporate clients achieve zero net deforestation.”

JP Morgan declined to comment, as it has to previous Global Witness investigations.

Santander, meanwhile, said it was working proactively with its beef processing clients to end deforestation, requiring them to have a “fully traceable supply chain that is deforestation-free by 2025 as a prerequisite for granting credit.”

The bank said this was the “most ambitious lending standard of any bank in the region” and it can “demand the early repayment of financing in cases where illegality is verified.”

Pressed on whether Santander felt JBS’s lack of compliance with its no deforestation legal obligations was a verified illegality, it said it “could not comment on the actions of our clients to third parties.”

BlackRock referred to its voting record at JBS’s annual shareholders meeting, where it objected to the company’s poor oversight of risk management processes, including on its sustainability performance.

Fidelity Management replied thanking us for the offer of comment, stating it was important to “understand different concerns and views and we appreciate your taking the time to share your thoughts about this matter.”

When pushed for a more substantive response, it did not reply.

BNP Paribas stated it updated its agriculture sector policy as of April 2021, and that it does “not finance clients that produce or purchase beef and soy from areas cleared or converted after 2008.”

When told that, in October 2021, JBS was found by prosecutors to be doing precisely what BNP’s updated policy claimed it would not finance, the bank remained silent.

Vanguard Group, Dimensional Fund Advisors and Deutsche Bank made no comment, despite multiple requests.

Credit where it’s not due

Credit Ratings Agencies are key actors in ensuring companies like JBS receive cash from financial institutions.

Companies pay these agencies to evaluate their capacity to pay off their debts, and investors then use the ratings to assess whether to invest in a company.

Yet analysts point out that environmental concerns are still not directly impacting ratings, even as agencies publicly tout their green credentials.

In 2020, we revealed three agencies that dominate the sector – S&P, Fitch and Moody’s – failed to account for JBS’s links to deforestation when upgrading its credit rating.

This was despite Amazon deforestation reaching a 12-year high and laws being developed limiting future markets for commodities linked to deforested land.

Moody’s

Moody’s said issues such as deforestation are only incorporated into a credit assessment if these affect the company’s capacity to pay off its debt.

Fitch said deforestation did have a significant impact on its credit assessment of JBS, while S&P did not reply to us at all.

Yet far from holding JBS to account for the multiple failings documented by us in 2020, in April last year Moody’s upgraded JBS’s credit rating once more, again failing to mention it driving deforestation.

The announcement referred to a methodology Moody’s uses to assess how environmental factors might affect a rating.

This states climate change may have a limited immediate impact on ratings as it develops “over very long-time frames.”

The Inter-Governmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) has found 23% of all greenhouse gas emissions due to human activity between 2007 and 2016 came from agriculture, forestry and land use.

Yet the Moody’s methodology makes no mention of any IPCC reports, nor of the Paris Climate Agreement’s emissions reduction plan.

This raises questions over what information it uses to assess how environmental issues impact JBS’s financial rating.

In response, Moody’s stated its “research reflects that cattle sourcing in Brazil has links to deforestation and we have identified managing this issue as a key credit challenge for JBS.”

Fitch

Fitch recently upgraded the company’s rating too.

While Fitch mentions JBS’s links to Amazon deforestation, it claimed this environmental risk was offset by the company’s global scope, so that its credit score reflects its “strong business profile.”

This appears to contradict its previous claim that environmental issues have a “significant impact on its rating.”

When we put this to Fitch, it said: “Credit ratings are forward-looking opinions on the relative ability of an entity or obligation to meet financial commitments. They do not directly address any risk other than credit risk.”

Fitch added that its analysis of a company’s performance on environmental, social and governance issues (ESG) is “not a measure or indication of good or bad ESG practice by a company.

"They inform investors about the impact of ESG factors on credit and the rating determinations.”

S&P

S&P also upgraded JBS’s credit rating in October 2020 and reaffirmed it in August last year.

In a comment piece published last April, part of which briefly mentioned JBS’s no deforestation commitments, S&P stated: “It remains unclear when and if attestations (JBS had originally pledged to monitor indirect suppliers by 2011) and technologies will halt the deforestation of the Amazon.”

This lack of clarity did not appear to impact the upgrade.

In response S&P said it incorporates ESG “credit factors into its credit rating analysis through the application of sector-specific criteria when we consider they are, or may be, relevant and material to our credit ratings.”

All this encourages investors to funnel cheap cash to JBS, even as its suppliers tear down the Amazon.

One year after the “Fire Day” in the Amazon. Christian Braga / Greenpeace

The importers

Grupo Mastrotto, headquartered in Italy, is a big global producer of leather for the upholstery, leather goods, footwear, clothing, aviation, boat and automotive sectors.

It boasts an annual turnover of €400 million and supplies the Volkswagen Group, owner of Audi, Porsche, Bentley, Lamborghini, Skoda, Seat and Bugatti. Some of Mastrotto’s other reported customers include Toyota.

IKEA has also been identified as a regular Mastrotto customer. It also has subsidiaries in Brazil that source leather.

The company is a member of the Leather Working Group (LWG), which claims its members implement environmental best practices throughout their supply chains.

The LWG has maintained Mastrotto’s "gold" rating for its environmental performance – despite criticism from an environmental group.

Last year, the NGO Earthsight revealed leather from the Gran Chaco region in Paráguay potentially entered Mastrotto’s supply chain.

This is the second largest forest in South America, and deforestation is rife.

Conversely, an LWG audit of the company’s traceability procedures gave it a 0% rating, showing it could not ensure leather did not originate from the destruction of the Gran Chaco’s forests.

When Earthsight asked Volkswagen whether it knew where Mastrotto’s leather came from, it replied that it “just asks suppliers for written confirmation that leather doesn’t come from the Amazon region.”

[Volkswagen] just asks suppliers for written confirmation that leather doesn’t come from the Amazon region

We can now reveal that in 2019, Mastrotto imported over 200,000kg of wet blue bovine leather from JBS’s tannery in the Amazon municipality of Maraba in Pará, where its slaughterhouses were found by prosecutors to purchase hundreds of thousands of cattle from ranches with illegal deforestation.

Throughout 2020, JBS also exported leather from these same slaughterhouses to an Italian company it owns, Conceria Priante.

As stated above, the beef giant bought cattle from at least 327 ranches that had committed illegal deforestation in that state between 2017 and 2019, some of which were linked to serious human rights abuses.

Cattle from further up JBS’s supply chain, meanwhile, came from ranches containing 98,000 hectares of deforestation.

Leather from any of those tainted cows could have ended up in Mastrotto’s warehouses.

Given that LWG claims Mastrotto has 0% traceability in its supply chains, the Italian company would have had no idea if its leather might have resulted from the destruction of the Amazon and associated crimes.

Replying to these allegations, Mastrotto said JBS leather imports represented a “negligible quantity” of its yearly production, adding that “following that purchase, Gruppo Mastrotto Spa no longer bought hides from JBS.”

Asked whether its operations in Brazil could trace the leather it buys there back to a ranch of origin, it stated a new audit result from the LWG would be forthcoming, but did not comment on the previous audit results.

Beef and leather risks not being included in the first list of commodities to be monitored for illegal deforestation under the UK’s Environment Act. Diego Giudice / Bloomberg via Getty Images

We asked Volkswagen Group, Toyota and IKEA whether they felt it acceptable to do business with a company that had a 0% traceability rating for the origin of its leather and that had sourced from problematic JBS slaughterhouses.

Volkswagen said its “purchasing policy excludes the use of leather material from South America that is linked to illegal deforestation.”

Toyota said it expected suppliers to have “respect for human rights (including diversity) and due consideration for the environment.”

IKEA, meanwhile, said it “requires suppliers to offer traceability of leather to direct farms which goes beyond the Leather Working Group’s (LWG) traceability requirements.”

It seems some brands appear to require more than others about the origin of their leather.

The supermarkets

Mastrotto is just one of many importers and supermarkets that trade in JBS products.

Trade data accessed by us shows that in 2020 alone, JBS exported beef products from Brazil worth almost €340 million to 160 companies located in Europe, some 30% of which went to the UK.

All of them are thus implicated in deforestation, and are buying a product linked to a company consistently failing to remove land-grabbing, cattle laundering and human rights abuses from its supply chains.

Legislation under development in the UK, EU and US, could make some of these products illegal in their respective markets.

However, until the details are agreed and the laws take effect, the deforestation associated with their backing of JBS looks set to continue.

Illegal deforestation is completely unacceptable

A swift investigation of the websites of UK supermarkets, such as Morrisons, Sainsbury’s, Iceland and Asda, for example, found in February 2022 all four offered cans with corned beef from JBS’s Brazilian operations.

Each of the cans bear the number code "385" from Brazil’s phytosanitary inspection service, which approve the export of the product.

This code refers to a JBS subsidiary located in Andradina, São Paulo, Brazil.

Responding to our investigation in 2020, Morrisons told The Times it would no longer source its own brand of corned beef from JBS.

Yet Morrisons still offers these other corned beef products originating from JBS, such as the Exeter brand.

Morrisons said it does “not have a direct trade relationship with JBS”.

“This branded product was bought as part of our world foods range and sold in a limited number of stores,” the supermarket said.

“Following the information provided by Global Witness we will discontinue this product.”

Sainsbury’s said it took “reports of this nature seriously,” adding it was investigating the matter and that it was “committed to responsible sourcing.”

The supermarket also said it was “working together with the wider industry to tackle deforestation in both our supply chains and beyond so we can play our part in preserving the essential ecosystems in the Amazon and Cerrado.”

A spokesperson for Sainsbury’s said it had a “strong track record of engaging on this issue” and would “talk to manufacturers responsible for the branded products available to our customers about their sourcing.”

Iceland admitted it sells “Exeter corned beef”.

It said the “allegations you have raised with respect to the overall operations within JBS and its supply chain will need to be addressed to and by JBS, we cannot address these matters on behalf of branded product manufacturers.”

The frozen food specialist added: “Illegal deforestation is completely unacceptable, and we are actively collaborating through initiatives such as the UK Soy Manifesto to tackle deforestation.

“We expect Iceland product suppliers to uphold our standards, and actively manage the risks to ensure legality all the way through the supply chain.”

Targeter UK, owner of the Exeter brand, did not reply despite many requests for comment.

Conclusion

International financiers, importers, supermarkets, credit rating agencies and auditors continued to back the biggest beef company in the world despite myriad red flags – some of which are revealed in this report and by many others.

Together they are setting in motion a chain of deforestation complicity reaching all the way down to corned beef in your local supermarket and European leather products.

Despite being called out repeatedly, JBS continues to source cattle from ranchers that have carried out Amazon deforestation.

These failures contradict its own legal obligations and its high profile COP26 "shared commitment to halting forest loss associated with agricultural commodity production and trade."

Cattle laundering, land-grabbing and slave labour also escape its checks – with ranchers like the Seronnis profiting from their crimes and barely held to account.

The company has given itself three more years to iron out problems with its Amazon suppliers – even though first it promised to deal with them over a decade ago.

When it breaches its no deforestation agreements with federal prosecutors, this has little consequence for its bottom line.

Meanwhile, audits that monitor JBS’s compliance with its legal agreements have not set out how they will report on the meat company’s screening of land-grabbers, a major driver of deforestation, while the audits of its voluntary no deforestation pledge repeatedly use small samples that do not capture non-compliant cases.

The perfect storm

Demonstration against Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), in Brussels. Hatim Kaghat / Belga / AFP via Getty Images

Deforestation may worsen as the Bolsonaro government seeks to legalise land theft linked to vast swathes of Amazon clearance that would enable companies like JBS to keep buying from environmentally damaging ranchers like the Seronnis.

It is a perfect storm, requiring more than voluntary due diligence proposals.

We have documented significant sums of financing from Western banks to companies like JBS in each of the last three years, continually undermining their own environmental policies.

The UK government’s own taskforce, set up to advise on how it should ensure British companies are not linked to deforestation, concluded that financial institutions need to be regulated to stop the money pipeline linked to forest clearance embedded in the supply chains of companies such as JBS.

Yet despite high-profile pledges at COP26 in Glasgow from world leaders to end and reverse deforestation by 2030, such laws are yet to be introduced in any financial hub.

Nor would JBS be engaged in these practices without a market for their tainted products. Leather importers such as Grupo Mastrotto fail to ask enough questions and do enough robust checks.

UK supermarkets such as Asda continued to sell beef products originating from JBS, even as some of the supermarkets stop buying their own branded products from it and as they publicly condemn the Bolsonaro government for its failures on deforestation.

Meanwhile, the destruction of the Amazon has hit a fifteen-year high.

Legislation in the EU and UK could put a squeeze on the market for commodities grown on deforested land and the issue is gaining traction in the US.

This report – and well publicised data on the cattle sector’s global deforestation footprint – demonstrates how necessary this is.

Current due diligence efforts are falling short of what consumers would expect.

Few people want products from companies that are failing to check on whether their products are linked to rainforest destruction and its associated human rights abuses.

While we wait for the implementation of much-needed legislation, JBS, and its financiers and prestigious clients, must demonstrate that deforestation and ranchers like the Seronnis have no place in their business model.

Recommendations

Governments in countries whose businesses import or finance beef and derived products in Brazil should:

- Introduce legislation requiring businesses, including the financial sector, to identify, prevent, mitigate and report on deforestation risk and related human rights risks

- Ensure legislation and policies aiming to tackle the role of imported products driving deforestation globally address cattle and derived products, including leather and canned beef

- Ensure that trade negotiations and development finance with Brazil do not increase the pressure on Brazil’s forests by promoting trade in cattle and derived products linked to deforestation

The financial actors, importers and supermarkets linked to JBS should:

- Suspend any services, financing or contracts with JBS, or products sourced from JBS, until it can be transparently shown the company is complying fully with its no deforestation agreements

- Ensure that where their services or relationship with JBS have caused, contributed to or are directly linked to deforestation and human rights abuses provide remedy and redress for affected communities and ecosystems

- Adopt a zero-tolerance policy for threats and attacks on environmental and human rights defenders

- Call for Brazilian state authorities to ensure that publicly available and independent data that tracks the lifecycle of cattle, such as cattle transport permits, are easily accessible

Credit Rating Agencies should:

- Suspend ratings services to JBS until such time as the company has addressed deforestation, land-grabs, cattle laundering and human rights abuses across its entire supply chain

JBS should:

- Ensure full, accessible and publicly available data on its cattle purchases which would allow independent scrutiny, including by civil society, of its entire supply chain and any actions taken against non-compliant suppliers identified

- Voluntarily enter into agreements with federal prosecutors to monitor all its cattle purchases across Brazil, and carry out independent annual audits that are published in full and that monitor 100% of its cattle buying

- Proactively check for land-grabbing and human rights abuse cases across its supply chain

- Require suppliers, at point of purchase, to provide full documentation that tracks the cattle’s lifecycle and owner throughout the supply chain as well as proof of full compliance with Brazil’s Forest Code

- Provide redress and remedy to communities affected by land-grabs and land-related disputes in its supply chain, recognising that in sourcing from ranchers involved JBS has sided with one party in the dispute and provided a material incentive for the prolonging of the land conflict

- Immediately commit to a mandatory reporting policy, which requires staff to report to relevant authorities if they become aware of any suspected breach of Brazilian law or human rights abuses by their suppliers

Future auditors of JBS’s voluntary no deforestation pledge should:

- Annually audit 100% of the beef company’s cattle purchases

- Ensure the relevant information on all ranches found to be non-compliant is published

- Guarantee that company comments provided to auditors to clarify or justify purchases from non-compliant ranchers be published in full

The Brazilian government should:

- Work to re-establish its credibility on deforestation and indigenous rights, given the escalation of deforestation and land rights violations in recent years and:

- Reverse the de-funding of enforcement of the Forest Code by the current administration

- Ensure that the rights of local communities, including of indigenous, afro-Brazilian and landless communities, are strengthened, rather than weakened

- Drop the legislative package that would legalise indigenous rights violations and further land-grabs

- Ensure that publicly available and independent data that tracks the lifecycle of cattle, such as cattle transport permits, are easily accessible

- Ensure each state has a due diligence system in place, such as "Selo Verde", that enables meatpackers to immediately check on the compliance of their suppliers with Brazil’s environmental law

Please see the methodology for our report Beef, Banks and the Brazilian Amazon to see how we came up with the number of ranches JBS purchased from contrary to its agreements and the illegal deforestation in them, as well as images of all the ranches in question.

Resource Library

Cash Cow

Download Resource