As countries return to unfinished COP16 biodiversity negotiations in Rome later this month, states must commit to people and nature instead of caving to the pressure of powerful corporate lobbying

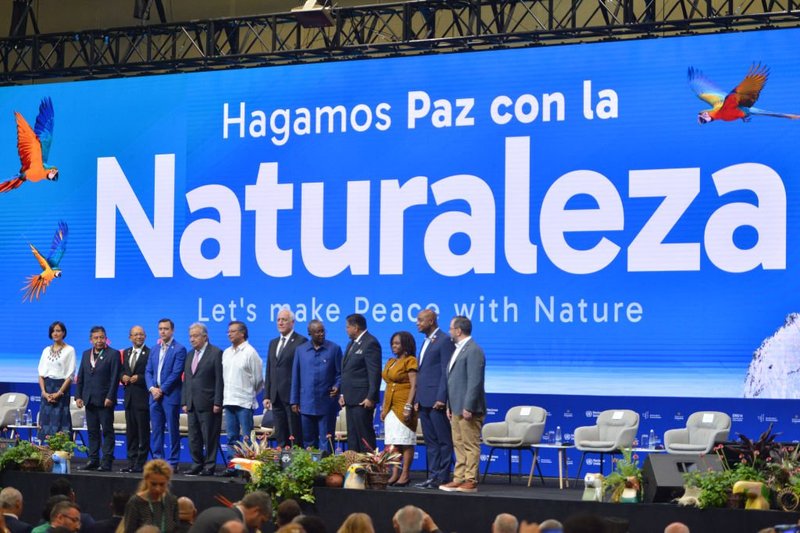

COP16, which concluded in early November in Cali, Colombia, set significant records.

It was the biodiversity conference with the highest attendance – and the most side events. It resulted in a number of remarkable grassroots victories, such as the establishment of the first Indigenous subsidiary body under the CBD convention and of a fund to collect money from pharmaceutical companiesprofiting from plants’ genetic information in their medicines.

As a result, COP16 was affectionately crowned the "People's COP" by Colombian Environment Minister Susana Muhamad.

COP16 President and Minister of Environment for Colombia, Susana Muhamad, speaks during the high-level sessions of COP16. Gabriel Aponte / Getty

But under the surface of last year’s UN biodiversity talks, there was also a notable anti-people power shift too. With record numbers of meat, oil and pesticide lobbyists at the conference, it’s clear that biodiversity has firmly entered the corporate radar – but not for the right reasons.

And as countries reconvene in Rome in late February to finalise unfinished negotiations, with a focus on mobilising finance for global biodiversity goals, concerns about corporate influence loom large.

At COP16, banks and multinational corporations - many of which are directly or indirectly responsible for deforestation of forest ecosystems like the Amazon - had a strong presence at the conference and did not hesitate to seize the publicity opportunity.

But many of the conversations we heard from these groups were not about agreeing on stricter regulations for destructive lending practices or more stringent targets to reduce their deforestation impacts. Rather, they were strategising how to generate even more profit – this time, from redeveloping the world that many of these corporations and banks are helping to destroy.

One five-star hotel in San Antonio, a wealthy area of the Colombian city, served as a networking hub. The title of another side panel made its objectives glaringly clear: "Opportunities blossom: How business can profit from nature's revival." At times, the panel discussed business opportunities amidst catastrophe.

One of the speakers was Natasha Santos, Director of Sustainability and Strategic Engagement at Bayer, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, invited to discuss “innovation”.

She spoke enthusiastically about the potential of seeds resistant to extreme climates, like tomatoes that could grow in deserts.

But she also made it clear that the company, which acquired the pesticide giant Monsanto in 2018, does not intend to stop producing one of its main products – Roundup. This weedkiller, which is based on glyphosate, has been deemed a probable “carcinogen” by studies and even contentiously by a US court. Bayer maintains it is safe.

Beyond human health issues, the use of pesticides like glyphosate disrupts environmental balance and impacts biodiversity itself. "We still see the need for chemicals in agriculture for the next decade because there are pests that cannot be controlled otherwise," Santos stated.

It killed huge amounts of freshwater rivers and fish species. It took away our entire spiritual connection with water

The panel was one of 26 events organised in Cali by the TNFD, or the “Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures”. This reporting scheme claims to “operationalise” Target 15 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which encourages signatory nations to take "legal, administrative, or political measures" to ensure that large companies and financial institutions monitor, assess, and transparently disclose their risks to nature.

TNFD’s aim is to progressively reduce businesses' negative impacts on biodiversity by identifying their harm to nature. However, many NGOs argue that the TNFD’s focus on reporting alone distracts from real solutions and does the opposite. Reporting risks to nature is not, these NGOs point out, the same as reducing them.

"The TNFD baseline is to report how nature impacts business, not how business impacts nature," explained Shona Hawkes from the Rainforest Action Network at one of the COP-16 panels.

Unlike regulation, the framework also fails, Hawk explained, to hold companies accountable for environmental violations when they do occur. TNFD did not respond to an email request for comment.

Over 500 businesses have already adopted the initiative, which helps to explain the TNFD's significant presence in Cali.

Among them is Brazilian multinational mining corporation Vale, a company whose two tailing dams tragically burst in Minas Gerais, Brazil, in 2015 and 2019, killing people, trees and animals.

In May 2024, my organisation SUMAÚMA reported that that Vale appropriated 24,000 hectares of public land in Carajás, Brazil's Amazon, for the world's largest iron ore project without providing official documents verifying land ownership to the courts. Vale denies the areas were public.

"For us, it is very difficult to live within our territory without water. Because on November 5, 2015, one of the greatest crimes occurred in Minas Gerais (...) It killed huge amounts of freshwater rivers and fish species. It took away our entire spiritual connection with water,” Shirley Krenak told the audience at a TNFD event.

Sossego mine, in Canaã dos Carajás. João Laet / SUMAÚMA

"We Indigenous Peoples are not against progress. We are against progress that kills and destroys biodiversity. And no matter how much you gather to seek economic solutions within the capitalist system, these solutions are not beneficial. You are killing people and killing biodiversity," she added.

Despite the agreement to realign international finance with an end to biodiversity loss, financial flows contributing to biodiversity loss continue to grow each year, according to a United Nations Environment Programme report released during last year's climate COP.

The study indicates that annually, around $7 trillion from public and private sectors is invested globally each year in activities that negatively impact nature – equivalent to 7% of the world's Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

This money is often generated and extracted from areas belonging to people like Ty’e Parakanã, a leader of the community, who went to COP16 to denounce the destruction of their territory to the world.

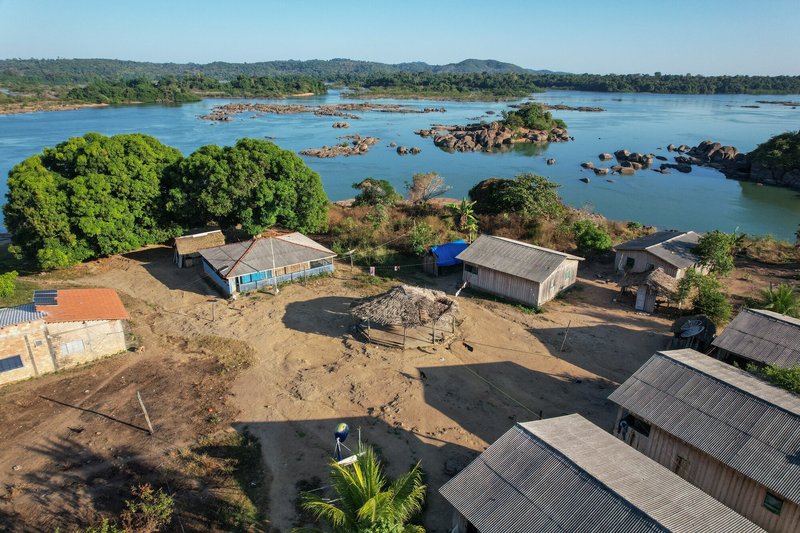

A Parakanã village in Apyterewa Indigenous land, Pará, Brazil. Cícero Pedrosa Neto / Global Witness

Ty'e is 37 years old, but he only lived in “Peace with Nature” (the theme of COP16) until he was seven. This was the age he began to see his land being plundered, the trees where he played cut down, the river where he bathed becoming polluted.

Over time, the territory became pasture, and nuts were replaced by cocoa monoculture. The Apyterewa territory has seen more deforestation in recent years than any other Indigenous territory in the Brazilian Amazon.

Ty'e had to leave his village when the Brazilian government launched an operation to expel the invaders last year. Many houses, including his own, were burnt down in acts of revenge.

Global Witness has revealed that JBS, a Brazilian meat giant whose operations are driving destruction of Apyterewa Indigenous land, is being financed by banks including Barclays, Vanguard and BlackRock. The Center for Climate Crime Analysis (CCCA) found that almost 8,000 heads of cattle raised within Apyterewa territory were hidden in JBS’ supply chain between 2018 and 2023.

Read the banks’ responses to Global Witness’s requests for comment.

Following that government operation to evict the occupiers, Ty'e rebuilt parts of his village. But its people have been targeted by violent attacks since then.

“Whoever financed the farmer to destroy our territory has to help us to reforest,” said Ty’e Parakanã. “Our territory no longer has trees, it only has pasture.”

Smoke from fires in Apyterewa Indigenous territory in Pará state, Brazil, July 2024. Cícero Pedrosa Neto / Global Witness

Taguide Picanarei – a member of one of the last remaining partially-uncontacted Indigenous groups in Paraguay – also lives in the Paraguayan Chaco, surrounded by cattle. Members of his extended family were forced to leave the mountain where they lived in isolation decades ago, due to the invasion of deforesters.

In the process, many of his relatives died – either from illness or hunger strikes protesting their forced separation from family members who still live in isolation. Taguide’s struggle continues as he and his family work to protect the last of the Chaco from commodity-driven deforestation.

“Today we are practically surrounded by cattle farms, which we know are financed by banks,” he says in Cali, speaking at a side event organised by the Forests & Finance Coalition.

An investigation by Global Witness last year found US banks top the list of creditors for meatpackers tied to the cattle-driven destruction of 75,000 hectares in Paraguay's Gran Chaco in the last three years.

For Taguide, the countries at COP16 are “absolutely incoherent" – they tell the world that they are preserving nature, but they support companies that destroy it.

Taguide and Ty'e know that many people profit from this destruction. They feel it in their bodies. And many people want to continue making a profit.

It is no surprise that in the COP that immediately followed the historic Kunming-Montreal agreement (which brought an ambitious plan to increase protected areas), so many companies saw this biodiversity COP as an opportunity to profit from the world's growing interest in nature.

But now the “People’s COP” runs the risk of being entirely captured by the corporate world, just like its more widely known cousin, the climate COP.

Last year, at COP29, in Baku, at least 1,773 fossil fuel lobbyists were present, according to analysis by the Kick Big Polluters Out (KBPO) coalition, in addition to 204 delegates from the agricultural sector, according to analysis by DeSmog. Among them, once again, was JBS.

While agreements crafted by countries – often lobbied by corporations - have historically struggled to address the concerns of those most impacted, the Kunming-Montreal agreement presents an opportunity to break this cycle – provided that meaningful participation continues to grow.

Target 22 already emphasises the need for full and equitable involvement of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in meeting the 2030 biodiversity targets.

While progress has been made in creating spaces for participation, such as the new subsidiary body established for the representation of Indigenous Peoples, sustained pressure from people and communities remains essential to ensure stronger regulations and accountability. Without it, commitments will fall short again.

For this target – or any of the targets – to be met, communities must be front and centre of negotiations. And their participation is needed not only in the global agreements, but in the national biodiversity action plans that countries are developing.

This last point is crucial. A global commitment is one thing, but ensuring that individual nations translate those commitments into actionable plans is another.

Many countries – especially those that are home to major financial institutions driving environmental harm – are well aware of the consequences of weak regulation.

The challenge is not just awareness, but the political will to act. This is where social participation plays a crucial role. And why, this year in Brazil, civil society have already begun to organise for the climate COP30, which takes place in Belém, Pará.

The first COP in the Amazon will be crucial for the future of the planet.

As seen in Cali, the pressure from Indigenous protestors, rallies and local communities was instrumental in securing key victories. Without sustained public pressure, commitments risk remaining empty promises.

For leaders gathering in Rome, high-income countries bear the heaviest responsibility. Will they stand with the communities fighting to protect what remains, or will they continue to allow corporate interests to cash in on the destruction of our natural world?

Fulfilling the potential of a true “People’s COP” process means rejecting a biodiversity market controlled by the same industries that are responsible for its destruction.

The outcome of these negotiations will determine whether COP16 is remembered as a turning point for nature – or yet another environment summit where profit trumped planet.