The Philippines’ mining industry is open for business. But with skyrocketing global demand for minerals – critical for the transition to green energy – Indigenous groups and the country’s rich biodiversity are increasingly at risk, Global Witness reveals

Demand for minerals used in green energy technologies – like nickel and copper – is soaring as countries shift to renewable energy in response to the climate crisis.

To keep pace with demand, consumer countries including EU member states, the US and China – which controls the world’s mineral processing – are vying for control over these resources.

Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos Jr is re-positioning the country as a leading exporter of "transition minerals", following the lifting of a nine-year moratorium on open-pit mining by his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte.

But a new investigation by Global Witness and Kalikasan People’s Network for the Environment (Kalikasan PNE) based on government data has found that Indigenous communities and biodiversity hotspots are already bearing the brunt of the Philippines’ mineral exploitation.

Indigenous Peoples have lost an area of land greater than the size of Timor Leste to mining projects in the last 30 years – equivalent to a fifth of their delineated territory.

On top of this, they have been disproportionately targeted with reprisals for speaking up against mining.

In total, more than a quarter of mining territories clash with protected, key biodiversity areas or important wetlands known as "Ramsar Sites" – crucial to mitigating the impacts of climate breakdown – resulting in substantial forest loss.

Since 2012, the Philippines has been ranked as the deadliest country in Asia for people protecting land and the environment, with mining linked to a third of all killings documented by Global Witness.

By boosting mining for transition minerals in the country, the global shift to renewable energy is already harming the lives and natural environment that communities rely on, placing them in increasing danger.

The "green" transition's dirty bootprint

Download Resource

The military has been linked to the highest number of documented killings and detentions of land and environmental defenders in the Philippines over the past decade.

These abuses have gone unchecked by President Marcos Jr as he oversees the militarisation of "green energy" infrastructure and increased targeting of human rights defenders and mining critics using anti-terror legislation.

Although the Philippines’ constitution guarantees the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ rights, and there are laws in place to guarantee their right to give "free, prior and informed consent" (FPIC), mining has led to major violations.

Communities have been intimidated, harassed and displaced by the military across the country.

By mapping hotspots in risks to communities and the environment in the Philippines, this report shows that without stronger protections, the so-called "green" mineral rush is likely to fuel further Indigenous land grabs, destroy crucial biodiversity and cause an uptick in militarisation and state-driven violence against defenders.

The world must rapidly transition away from fossil fuels and that will require transition minerals. But the energy transition cannot come at the expense of communities and climate-critical biodiversity.

Our findings follow a Global Witness analysis that showed emerging countries like the Philippines were disproportionately affected by violence and protests linked to mining, while profits were mostly captured by companies from wealthier economies.

Transition minerals threaten some of the world’s most precious biodiversity

The Philippines is the world’s second largest producer of nickel – a key component for electric vehicle batteries.

By 2040, global demand for this mineral from the renewable sector is expected to increase seven-fold, fuelled by the car industry.

On top of this, the Philippines has major untapped reserves of copper, chromite, silver and zinc, used in renewable energy technologies like wind turbines and solar panels.

Currently, a fifth of the Philippines’ land mass is covered by mining and exploration permits.

This figure is set to increase as the government courts foreign investment in its mining industry.

In early 2024, the government bowed to industry pressure and agreed to begin fast tracking mining permits, something advocacy groups say will imperil communities and nature.

Mining for nickel and copper – two of the country’s main mineral exports – is an extremely dirty business.

The damage is visible from space. Communities have watched in horror as waters turn red from toxic waste leaking into the environment. Fish die and crops wilt, wiping out livelihoods and destroying ecosystems.

Our analysis shows that more than a quarter of the overall territory of transition mineral tenements overlaps with protected or key biodiversity areas or Ramsar Sites.

Nearly half of all individual permits clash to some extent with these important ecological zones.

More than 230,000 hectares of tree cover has been lost in regions designated for mining since 2010 – an area nearly three times the size of New York City.

Filipino law prohibits mining in legally protected areas, such as critical watersheds, old growth forests and wildlife sanctuaries.

But our analysis shows that at least one in five transition mineral permits encroach on land that is meant to be legally protected from mining.

“The aggressive push for mining in the Philippines … exposes the deep contradictions in the Philippine government’s approach to sustainability,” said Beverly Longid, Global Coordinator for KATRIBU (National Alliance of Indigenous Peoples Organizations in the Philippines).

“While we are told that the energy transition is meant to mitigate the climate crisis, the reality on the ground is that it is fuelling the same systems of exploitation that have harmed our lands and people for generations.”

The Philippines is among 18 mega-biodiverse countries in the world, with the fifth most diverse plant life.

Preserving the world’s biodiversity – often found in forests, peatlands and mangroves – is crucial to fending off the impacts of climate change.

The Philippines is also one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world and ranks among the most vulnerable to climate change.

Nearly half of the total area of nickel projects clash with key biodiversity areas in the Philippines, while copper has the biggest territorial overlap with biodiversity hotspots of any transition mineral.

In nickel-rich Palawan, a lush western island home to some of the world’s most diverse flora and fauna, we found total overlap between mining areas and biodiversity zones.

In the mining hub Surigao Del Sur in Caraga in north-eastern Mindanao, almost 70% of nickel mining zones and nearly 80% of copper mining zones clashed with biodiversity hotspots.

Satellite image comparison of Nickel mining in southern Palawan: summer 2016 vs. summer 2024

Indigenous Peoples hit with land grab the size of a small country

Indigenous communities are estimated to make up around 10-20% of the Philippines population. They occupy around 14 million hectares of land, which comprises 75% of the country’s remaining forest cover, according to civil society groups.

Indigenous Peoples face massive land grabs from the ongoing mining drive. More than a quarter of the entire land mass of transition mineral zones encroaches on demarcated Indigenous land.

In total, Indigenous communities have lost a land area bigger than the size of Timor-Leste (or 2.2 million football fields) to mining tenements in the Philippines since the 1990s.

This is an astonishing fifth of their delineated land. Most of the mining operations that threaten Indigenous land are producing transition minerals.

These figures only include demarcated ancestral domains and will therefore be a significant underestimate of Indigenous land loss.

The land delineated by the authorities and used in this analysis makes up less than half of the total territory estimated to belong to Indigenous Peoples.

The process for recognising ancestral domains is expensive, bureaucratic and can take up to 20 years, with political elites accused of circumventing the law to deny Indigenous communities their rights.

Eighty ancestral domain claims are still waiting to be processed.

The state body mandated to oversee this process, the National Commission for Indigenous Peoples (NCIP), has been criticised for dragging its feet and betraying Indigenous Peoples.

The commission has been accused of failing to protect the legal right of Indigenous communities to say no to mining projects.

The FPIC process has been marred by corruption scandals and conflicts of interest, with the NCIP allegedly working with the military and companies to pressure communities into accepting projects.

The NCIP is pushing forward with plans to “fast track” the FPIC process for energy and mining projects, which has sparked serious alarm.

Nearly half of the territory of ancestral domains overlaps with biodiversity hotspots. Indigenous communities are credited with conserving these territories through traditional practices.

It should be clear that protecting biodiversity means protecting Indigenous rights

The rush for transition minerals is amplifying the need to protect Indigenous communities as custodians of biodiversity and climate resilience in the Philippines.

Transition mineral tenements are more than three times as likely to overlap with both biodiversity hotspots and Indigenous lands than other mining activities.

“Our communities have lived in harmony with the land for centuries, understanding that protecting biodiversity is essential not just for our survival but for the survival of all life,” said Beverly Longid.

“It should be clear that protecting biodiversity means protecting Indigenous rights … The more our lands are taken from us, the more vulnerable our ecosystems become to destruction.”

Military is single biggest threat to Indigenous defenders

Indigenous communities have long defended their lands against incursions by mining companies and the military. All too often, they’ve paid with their lives.

Indigenous Peoples account for a staggering one-third of land and environmental defender killings in the Philippines in 2012-23. Neary half of these cases were linked to mining.

The military is the single biggest perpetrator of defender killings in the Philippines, especially of Indigenous Peoples. It was responsible for 64 out of 117 killings of Indigenous defenders Global Witness has documented between 2012-23.

Men with guns often guard the mines. There are special military and paramilitary units mandated to protect state resources. They work closely with mining companies and have been linked to a spree of abuses, including sexual violence.

The army justifies its presence on the grounds of a decades-old conflict with the Communist Party of the Philippines and its armed wing the New People’s Army (NPA), which is known to target mine sites.

The NPA says mining companies exploit local, Indigenous communities and workers to advance neo-liberal and elite interests.

Our analysis shows that the four deadliest regions in the Philippines for Indigenous defenders and anti-mining activists all experience high levels of conflict.

Counter-insurgency efforts have also seen troops move into resource-rich regions where communities oppose mining.

Civil society groups have long accused the Filipino state of using military force to crush resistance to extractive projects and expel Indigenous people from their land to make way for developments.

According to an October 2024 report by Altermidya, only 17% of military bombardments actually hit rebel targets, with the rest terrorising local communities and Indigenous Peoples.

“I have personally witnessed how military operations are employed to threaten Indigenous leaders and activists, labelling them as insurgents or terrorists simply for opposing mining incursions,” said Father Raymond Montero-Ambray, a Catholic priest and Indigenous rights supporter based in Mindanao.

“This approach justifies the militarisation of their territories under the pretence of security, effectively silencing any resistance to the destructive practices associated with mining.”

Anyone who speaks out against resource developments is vulnerable to reprisals.

In late 2018, the then President Rodrigo Duterte formed a new counter-insurgency outfit – the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) – mandated to crush the insurgency.

The taskforce has representatives from across government departments, including the Indigenous rights agency NCIP, whose chair sits on the executive committee.

NTF-ELCAC has taken a leading role in smearing human rights and environmental activists as communist rebels, a form of harassment known as "red-tagging".

The government of Marcos Jr has failed to curb military killings of land and environmental defenders.

While killings have decreased since the end of Duterte’s presidency, the percentage of killings carried out by the military has surged over the past two years.

In 2023, the military was responsible for 15 out of 17 defender killings. In 2022, eight out of 11 defenders were killed by the military.

Enforced disappearances have skyrocketed during Marcos Jr’s term in office, which campaigners say is having a chilling effect on communities.

Global Witness recorded seven defender disappearances in 2023 alone. Most abductions reportedly happen in heavily militarised areas.

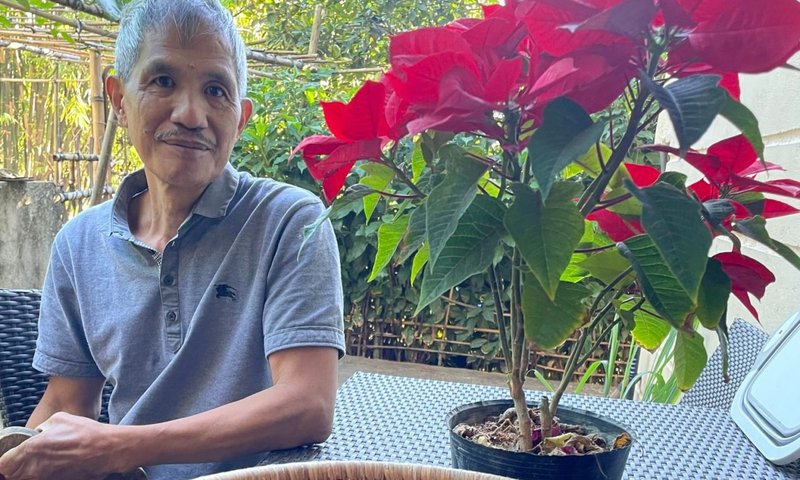

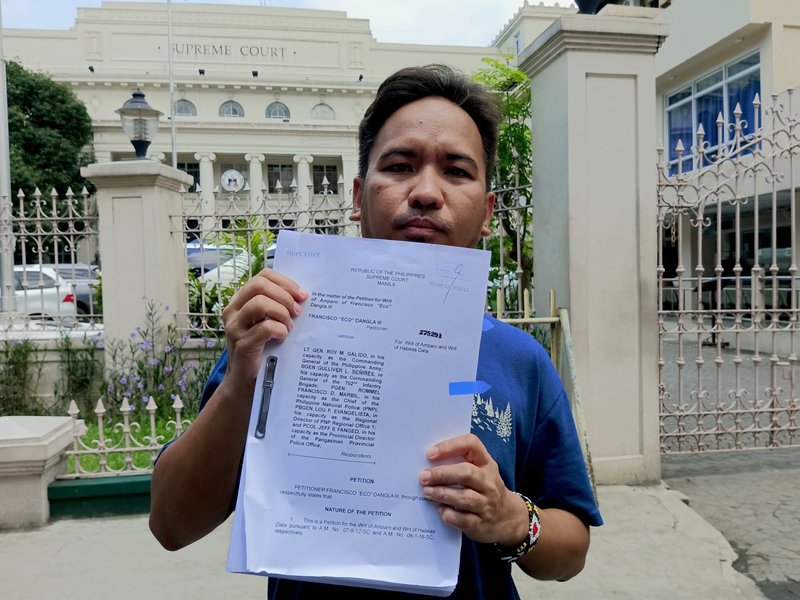

“[Marcos Jr] is presenting a more diplomatic and presidential image, but underneath it’s different. He's just continuing the repressive policies of Duterte,” said Francisco "Eco" Dangla III, an activist from northern Philippines, who was grabbed from his tricycle earlier this year, likely by state agents according to reports.

He was blindfolded and held in isolation for three days.

The growing scourge of "red-tagging"

Jennifer Awingan-Taggaoa, a researcher from the Indigenous rights organisation Cordillera Peoples’ Alliance, was at home one morning in January 2023, when her dogs started barking wildly.

Before long, armed police had surrounded her house, terrifying her young children inside.

The police handed her an arrest warrant for armed rebellion. An army officer had accused her and six other mostly Indigenous defenders of being insurgents.

She was taken away by police as her family cried.

“I asked if this was happening because I was an activist,” she recalled.

When their cases were dismissed by a regional court a few months later for a lack of evidence, the government responded by declaring four of them “terrorists”.

The move was backed by the NTF-ELCAC. All four had been harassed, threatened and smeared on social media or accused of other violent crimes in the past.

“These attacks have taken a heavy toll, leaving me and my family traumatised and constantly under suspicion,” explained Stephen Tauli, one of the six defenders "red-tagged" alongside Jennifer.

The year before, he was abducted by suspected state agents, blindfolded, threatened with violence and interrogated for hours, before being left on the side of a road.

“I now have to restrict my movements, limit travel, and ensure I always have a companion when going out.”

Jennifer is also stalked by the fear of reprisals.

“Being branded a ‘terrorist’ … has deeply impacted my ability to work ... It isolates me, stripping away the legitimacy of my activities and casting doubt on my intentions,” she explained. “It paints me as a target.”

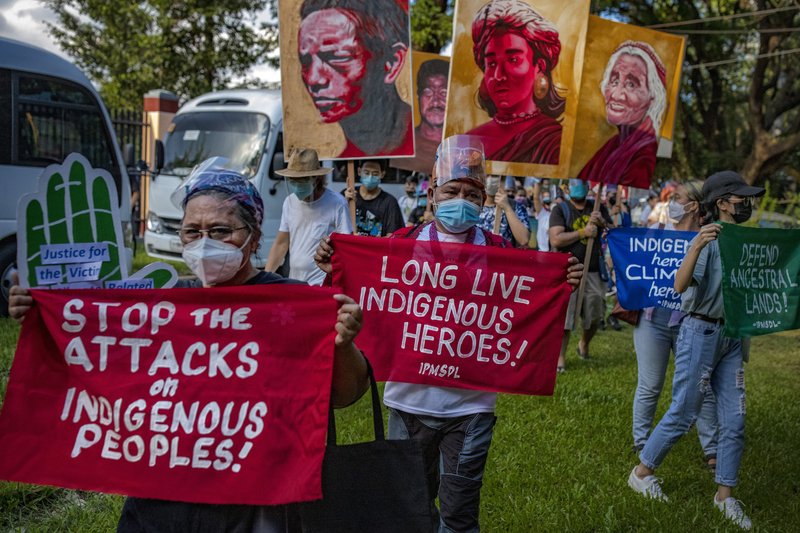

They are among a growing number of activists slapped with rebellion or terrorism charges for speaking out against resource projects.

Indigenous defenders were targeted in nearly a third of all incidents of arrest documented by human rights organisation Forum-Asia since 2016. Half of the cases involved anti-mining activists.

UN human rights experts have called on the Philippines to urgently end red-tagging.

Climate activists hold up signs next to portraits of slain Philippine environmental defenders at a Global Day of Action for Climate Justice protest on November 06, 2021 in Quezon city, Metro Manila, Philippines. Ezra Acayan / Getty Images

The armed forces of the Philippines (AFP) have been involved in more than 45% of recorded cases of arrest of people identified as land or environmental defenders since 2017.

By comparison, the military was involved in only 8% of arrests of other types of human rights defenders.

Two out of three cases of arrest targeting Indigenous defenders were carried out by the military.

“The most vocal and effective organisations are … red-tagged or vilified by the government,” said Lia Mai Torres, Executive Director of the Center for Environmental Concerns.

“The government can formally designate individuals and organisations as terrorists, freez[ing] the bank accounts and assets of individuals and organisations even if they are just under suspicion.”

Defenders have been abducted and disappeared as a result.

The most vocal and effective organisations are … red-tagged or vilified by the government

Last year, two Indigenous activists – Gene Roz Jamil "Bazoo" de Jesus and Dexter Capuyan – were snatched by suspected state operatives in the northern Philippines. Dexter had previously been red-tagged by the government. They haven’t been seen since their abduction.

In May 2024, the Philippines Supreme Court declared red-tagging a threat to a person’s “right to life, liberty, or security.”

But Marcos Jr has ruled out disbanding the NTF-ELCAC and downplayed its red-tagging record.

He has increasingly weaponised anti-terrorist financing laws, which are being used against "red-tagged" human rights and environmental defenders.

His administration is increasingly using the language of climate change and mitigation to justify security interventions and the militarisation of energy infrastructure.

The current National Security Policy includes specific chapters on climate change and mitigation.

“Attacks on environmental defenders are more systematised now because all the counter-insurgency infrastructure is in place,” added Torres.

“We are also seeing the ‘greenwashing’ of security interventions. Framing climate within the national security strategy implies the use of military solutions as well.”

Mindanao: Standing against mining and militarisation

Alberto Cuartero was out for drinks with friends in September 2024 when a motorbike rider drove by and peppered them with bullets. Alberto and his friend Ronde Arpilleda died on the spot.

Alberto was an outspoken activist mobilising communities against the expansion of nickel mines in northeastern Mindanao.

His community in Carmen, Surigao del Sur, has witnessed a rash of mineral developments in recent years, poisoning water and farmland.

Alberto challenged these companies, recently testifying in court about an entity accused of falsifying an exploration permit.

The southern island of Mindanao has the highest-by-far recorded number of killings of Indigenous and anti-mining activists in the past decade.

It also has the largest overlap between mining tenements and ancestral domains of the Philippines’ main islands – with nearly half of the territory of mining activities clashing with Indigenous land.

The five deadliest regions for Indigenous mining activists – all but one on Mindanao – were among the regions with the biggest percentage of territorial overlap between mining tenements and ancestral domains.

Almost half of all the transition minerals mining tenements in Mindanao overlapped with both ancestral domains and key biodiversity areas.

Nearly two-thirds of all the Indigenous land claimed by mining companies for transition minerals are on Mindanao.

Indigenous communities native to Mindanao, collectively known as Lumads, have been disproportionately affected.

Manobos, one of the Lumad communities on Mindanao, have paid a heavy price.

Nearly a quarter of the area of all types of mining on formally recognised Indigenous land affect Manobo communities, despite them only making up around 7% of the Philippines’ Indigenous population.

Other Lumad communities on the island, such as Mandaya, Mamanwa and Subanen, were also heavily impacted by mining, including transition mineral mining.

Lumads risk becoming “collateral damage” in a global rush for resources, according to Kat Dalon, a Manobo campaigner from Mindanao.

“We, the Indigenous peoples, are pushed aside – driven off our lands, losing our homes, and endangered due to militarisation and violence.”

Most of the Manobo land occupied by transition mineral permits were in Caraga – one of the most dangerous regions in the Philippines to be an Indigenous anti-mining activist.

Caraga is a hub for nickel production, extracting ore worth over 37 billion pesos (around £500,000,000) in 2023.

In Surigao Del Sur in southern Caraga – dubbed the "mining capital of the Philippines" – 84% of nickel-mining tenements clash with both key biodiversity areas and Indigenous lands.

It’s among the top three most dangerous provinces for anti-mining and Indigenous activists.

UN experts have warned about the devastating impact of militarisation on Indigenous communities on Mindanao.

We, the Indigenous peoples, are pushed aside – driven off our lands, losing our homes, and endangered due to militarisation and violence

There are reports of soldiers systematically destroying or vandalising independent Lumad schools, and arresting or even killing teachers.

The military claims that the schools train insurgents, but Indigenous communities see these assaults as attempts to undermine their resistance to environmental plunder.

Most of the cases of anti-mining campaigners being detained or arrested were also on Mindanao.

Julieta Gomez has campaigned against mining injustices in Caraga for years, where nickel companies have been accused of dispatching paramilitaries to force communities off their land.

On a visit to the capital in 2021, she and fellow Lumad activist Niezel Velasco had their doors kicked in by a joint force of military and police. They were accused of murder and hoarding munitions, charges they and activist groups dismiss as fabricated.

They are still in prison.

Indigenous communities in uphill battle against "green" mining

The Philippines’ mining resurgence could spell disaster for local communities and the environment.

Communities mobilising against mining projects face mounting pressure, as global superpowers scramble for access to the country’s resource wealth.

The Philippines is presenting itself as a strategic partner for governments trying to challenge China’s dominance in the sector.

Earlier this year, the EU resurrected talks on a trade agreement with the Philippines, which could see the bloc get access to the country’s coveted minerals. There are concerns that trade interests will trump human rights.

The US, meanwhile, agreed a $135 million package of aid that includes support for critical minerals extraction and clean-energy investments.

Authorities are trying to revive plans to mine one of Southeast Asia’s largest mining areas, containing copper and gold, in South Cotabato, Mindanao.

The Tampakan project, connected to an ally of President Marcos Jr, was linked to a horrific massacre of an entire Blaan family, including a pregnant woman and two children, in 2012.

The communities are still waiting for justice. But across the country, people are fighting back.

Last year, Indigenous Pala’wan obtained a legal order requiring a nickel company and the government to address the environmental impacts of its operations.

The court found that the authorities had displayed “inaction” and “indifference” to the concerns of Indigenous communities about mining in a protected area of their land.

Corruption allegations had marred the free, prior and informed consent process, which eventually resulted in the NCIP ordering the company to “cease and desist” until grievances are resolved.

Pala’wan communities say they were inspired by the people on Sibuyan – a small island known as the "Galapagos of Asia" – who mobilised to resist a nickel-mining company earlier that year.

In other cases, communities are simply fighting to get a fairer deal, such as larger royalty payments or the ability to renegotiate contracts with mining companies.

Civil society groups are calling for a new mining law to protect communities and the environment during the energy transition.

They want meaningful reform of regulatory bodies, including NCIP, and free, prior and informed consent procedures, the perpetrators of attacks against defenders to be held to account, and demilitarisation of Indigenous land.

“At the heart of biodiversity conservation is the recognition that Indigenous Peoples are the original environmental stewards. Yet, rather than being supported in our role, we are displaced, criminalised and stripped of our sovereignty,” said Beverly Longid.

“If the global community is truly committed to ecological justice, it must begin by defending the rights of Indigenous Peoples and restoring our control over our ancestral lands.”

Recommendations

The Philippine Government

These were developed in collaboration with 18 civil society and Indigenous organisations from the Philippines.

Strengthen protections for Indigenous Peoples and biodiversity:

- Review the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) to protect the right of “free, prior and informed consent” (FPIC) to ensure meaningful consent from Indigenous communities. This must address other laws that contradict or weaken IPRA

- Formally recognise the role of Indigenous Peoples’ customary governance systems and Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Practices in biodiversity protection

- Amend the country’s Writ of Kalikasan framework to provide stronger preventative legal remedies for environmental harms and violations of ecological rights. Establish a special environmental court to consider claims

- Ratify and implement the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (1989), also known as International Labour Organization Convention 169, a legally binding agreement protecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples

End the militarisation of mining areas and hold perpetrators of human rights violations to account:

- Withdraw military deployments from mining areas

- Abolish the NTF-ELCAC and criminalise red-tagging

- Repeal the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 and the Terrorism Financing Prevention and Suppression Act of 2012

- Dismantle paramilitary groups and revoke Executive Order 546

Repeal the 1995 Mining Act and create a stronger legal framework that prioritises environmental sustainability, Indigenous rights and long-term community welfare:

- Conduct an independent and transparent audit of mining companies to ensure compliance with national and international business and human rights principles and hold those violating these principles accountable

- Strengthen and implement existing laws to prevent mining in legally protected and key biodiversity areas, including those found in ancestral domains

- Conduct an independent review of the national security policy’s use of state forces, paramilitaries, private armed groups, and corporate security personnel to enable and protect mining operations

Abolish the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) and overhaul mechanisms for protecting Indigenous rights:

- Establish a new elected Council of Elders, chosen by Indigenous Peoples, to ensure genuine representation and accountability, and to facilitate the meaningful participation of Indigenous Communities in the creation and implementation of safeguards to protect their lands, livelihoods, and cultural heritage from exploitation

- Establish an independent truth and justice commission to investigate cases where the NCIP has either facilitated or failed to prevent violations of Indigenous rights, particularly in relation to mining projects and forced land acquisitions. This commission should have the mandate to impose appropriate sanctions, and ensure that reparations are provided to affected communities

Pass specific legislation to protect defenders against violence, harassment and threats, including the Environmental Defenders Bill and a Human Rights Defenders Act:

- Review and repeal all outdated development plans that prioritise extractive industries at the expense of the environment and local communities. Any future projects should recognise the vital role of Indigenous Peoples’ customary governance systems and Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Practices in biodiversity protection.

Mining and energy companies

Do not mine in protected and key biodiversity areas.

Respect Indigenous rights and self-determination, including the right to Free, Prior and Informed Consent:

- Respect Indigenous communities’ right to say no to mining projects. FPIC must be a genuine community-led process, ensuring that Indigenous Peoples have the power to reject projects without fear of coercion or retaliation

- Uphold international standards on business and human rights, and mitigate any harms caused by inadequate national laws or collaborations with government agencies, such as the NCIP

- In cases where Indigenous communities agree to allow mining operations, strictly comply with environmental laws and draw up environmental mitigation measures. Halt mining operations in areas where it has been alleged that FPIC has been coerced or manipulated pending a full and independent investigation

- Regularly engage independent third-party auditors to assess compliance with FPIC principles, environmental protections, and other critical standards, providing transparent reporting to stakeholders

Adhere to the highest international environmental, social and governance standards, including the OECD’s Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Guidance), the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

- Support independent and transparent audits of all mining operations, focusing on compliance with human rights and environmental standards.

- Consider becoming a member of International Responsible Mining Assurance.

- In areas already impacted by mining, fund financial reparations, restoration and reforestation initiatives to mitigate biodiversity loss. Create funds specifically aimed at compensating individuals and communities affected by corporate practices through direct financial compensation or investments in community development initiatives, health, and education programs.

- In areas already impacted by mining, acknowledge corporate responsibility for harm. Publicly recognise the negative impacts of operations on local communities and the environment.

- Establish and implement transparent mechanisms to monitor the effectiveness of reparations efforts. Hold regular assessments, soliciting community feedback, to ensure that initiatives are impactful and really hold companies accountable for the harm they caused.

Develop people-centred Social Development and Management Plans that genuinely reflect the needs and perspectives of host communities. Actively incorporate local communities into the planning and decision-making of these plans to foster trust, strengthen community relations, and ensure long-lasting positive impacts.

- Invest in Community-Driven Development and Reparation Initiatives

- Establish funds and collaborative programs to support environmental rehabilitation and social services in communities impacted by mining, especially those involved in supply chains

- Encourage supplier investment in reparation initiatives to mitigate biodiversity loss and support community health, education, and infrastructure development

Support the proposed legislative reforms and human rights protections described above.

Financial and multilateral institutions

- Make public reporting on sourcing a requirement of financial support or investment

- Use leverage, such as the threat of withdrawing financial support, to dissuade companies from continuing to source from companies involved in human rights abuses

- Just Energy Transition Partnerships should be screened against international environmental, social and governance standards and the recommendations of the UN Secretary General’s panel on transition minerals to expressly exclude projects which fall foul of these criteria

The EU

The EU should either suspend talks on a trade deal with the Philippines or make significant improvements to current human rights and environmental abuses a key steppingstone for further discussions.

- The rights of, and threats to, the country's Indigenous peoples and their vulnerable position in the just transition must be given special attention in EU-Philippines trade talks. The review of the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act to ensure rigorous enforcement of the constitutional guarantee of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) must be part of a pre-conditionality approach.

- As part of the trade talks, the country's mining legislation, such as the Mining Act, needs to be improved to create a more robust legal framework that prioritises environmental sustainability, Indigenous rights and long-term community welfare.

New Global Gateway projects with the Philippines must be consistent with the principles of the EU's development strategy, with a view to reaffirming the primary tasks of the EU's development objectives, such as poverty reduction, sustainable development, good governance and the protection of human rights.

- All projects undertaken and companies involved must follow the highest standards, and for those in scope, all Global Gateway projects must comply with the CSDDD standards once implemented in EU Member States.

The EU Commission should support the timely implementation of the CSDDD in its EU Member States in order to meet the 2026 implementation deadline.

- EU Member States should pay particular attention to the establishment of a national supervisory authority that is well resourced and equipped to monitor the compliance of companies in scope of the CSDDD

- This national supervisory authority must ensure that its complaints mechanism is responsive and accessible to affected communities, and that it is equipped and prepared to impose sanctions if companies fail to comply with the provisions of the CSDDD

The US

- The US should ensure that none of its development aid is going towards mining projects that are perpetuating human rights abuses and ecological damage. USAID should specifically screen financing for mineral development to ensure it is not contributing to the abuses outlined in the report

- Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity must focus on supply chains which are sustainable. This means that only projects with express permission and cooperations from communities should be considered

Methodology and acknowledgements

Our investigation was based on obtaining, analysing and visualising different government and civil society datasets. Our full methodology is outlined in the report.

Special thanks to everyone who helped with this process, especially A Cervantes, D Cotia, T Olarve, J Pagdanganan, J Santos, S Suringa and I Taroma.

The "green" transition's dirty bootprint

Download Resource