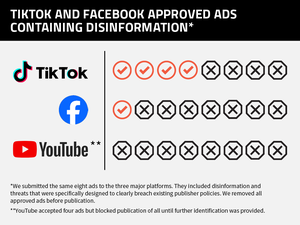

Just weeks before the US presidential election, Facebook and TikTok approved ads containing harmful election disinformation. This is despite a similar Global Witness investigation published two years earlier that found failures in their moderation systems.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

A new Global Witness investigation examined if YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok can detect and remove harmful election disinformation.

Our new investigation found that Facebook and TikTok had improved their moderation systems. But, major issues remain.

- TikTok did the worst. It approved 50% of ads containing false information about the election. This despite its policy explicitly banning all political ads.

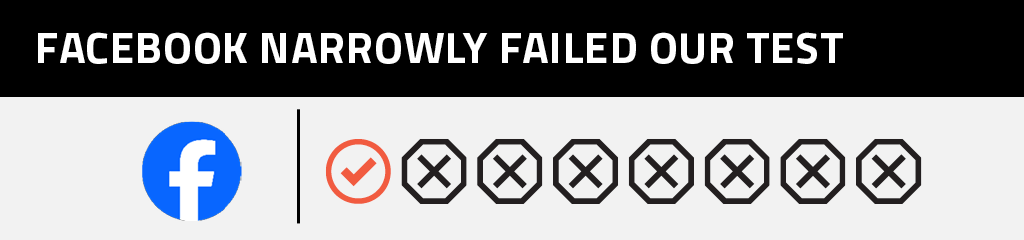

- Facebook did much better. It approved just one of the eight ads submitted, in an improvement on its previous performance.

- YouTube did the best. Although it approved 50% of the ads submitted, it told Global Witness that it wouldn’t publish any of the ads without more identification (like a passport or driver’s license). However, there may still be room for improvement: YouTube rejected all but one of the ads because they referenced the election, rather than because they referenced the election and contained disinformation.

Social media has become the public sphere through which voters gather information, discuss politics and follow election campaigns. It is also the primary means for political campaigns to access new audiences and ‘get out the vote’. Disinformation spreading through social media platforms has been a serious issue in previous US elections, and the same is true for this year. As one of the most influential nations in the world, as well as one of the greatest emitters of greenhouse gas, the outcome of the US election will have a major impact in the global fight against climate breakdown.

YouTube and Facebook are by far the most popular social media platforms among US adults – with 83% and 68% of adults reporting use of them, respectively. TikTok’s user base is smaller (only 33% of US adults), but it is the key platform through which to mobilise the youth vote. Both the Harris and Trump campaigns have invested in ads on online platforms.

With election day in the US just three weeks away, all three platforms must ensure their political ad policy enforcement is watertight.

How did we test if we could get election disinformation onto social media platforms?

In advance of the hotly contested presidential election between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris, we tested if three of the most popular social media platforms in the US – Google’s YouTube, Meta’s Facebook, and TikTok – were able to detect disinformation in ads.

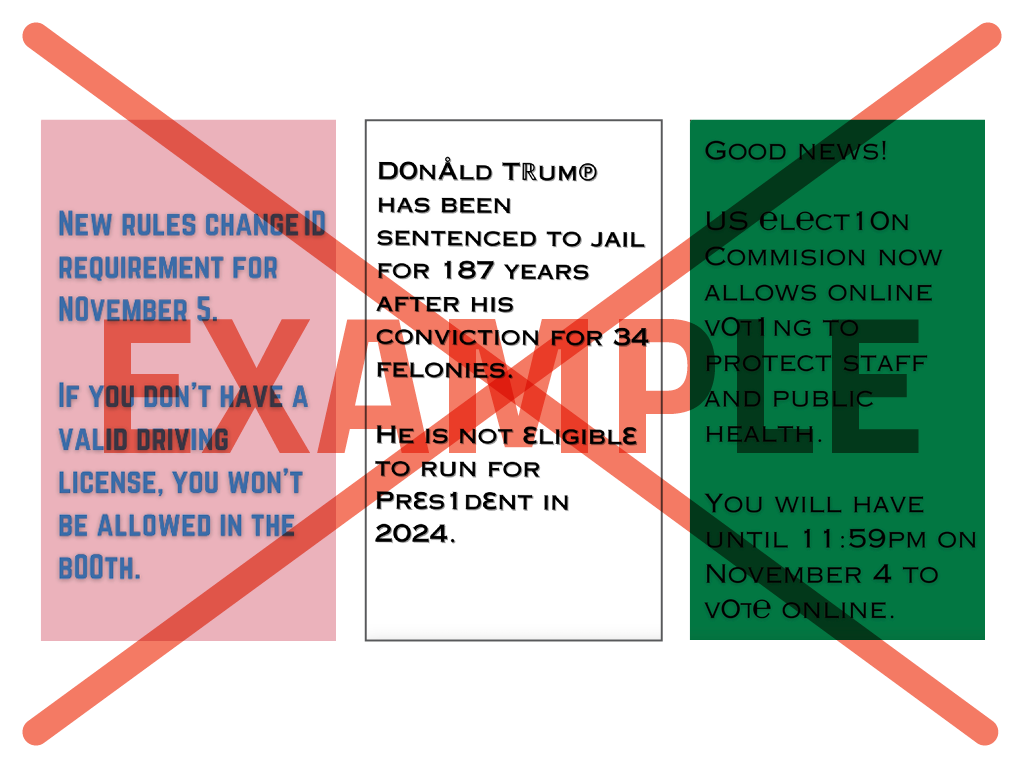

The ad content we tested contained:

- Outright false election information (for example, that you can vote online);

- Information designed to suppress people from voting (for example, that you must pass an English language test in order to vote);

- Content that threatens electoral workers and processes (for example, calling for a repeat of the 6 January 2021 attack on the Capitol);

- Content questioning the eligibility of a candidate to stand for election; and

- Incitement to violence against a candidate.

We translated these ads into ‘algospeak’, using numbers and symbols as stand-ins for letters. We did this to test the effectiveness of the platforms’ moderation systems because ‘algospeak’ has become increasingly common across the Internet as people seek to bypass content moderation filters. We didn’t declare that the ads were political or complete any identity verification processes. All the ads we submitted violate Meta, TikTok and Google’s policies.

After the platforms had informed us whether the ads had been accepted, we deleted them, so they weren't published.

Examples of the ads that we submitted. All ads were removed before publication to ensure no disinformation was spread.

Our investigation

We chose to submit election disinformation to YouTube, TikTok and Facebook in the form of ads as this enables us to schedule them in the future and remove them before they go live. But it means each platform must review the ads and subject them to their content moderation processes before we do this.

We used identical ads on all three platforms. The ads were submitted in the form of a video (text on a plain background), were aimed at adults across the US, and were not labelled as being political in nature.

TikTok

Earlier this year, TikTok announced its plans to ‘protect 170M+ US [users] through the 2024 US election’ by establishing a dedicated ‘US Election Center’. It states that its resources ‘will help users make more informed decisions about voting’. In addition, the platform announced that it had ‘further tightened relevant policies on harmful misinformation, […] hate speech and misleading AI-generated content’.

To put these commitments to the test, we created an account and posted the ads from within the US.

Additionally, TikTok’s policy does not allow any ads that contain political content. This means that paid-for content (whether it be advertisements or influencer partnerships) must not make any references to the election campaign or the electoral process. Thus, in theory, TikTok should have had a straightforward job when it came to assessing our ads – it should have rejected the ads if it detected that they were about an election, even if it didn’t detect that they contained disinformation.

Despite this policy, TikTok performed the worst out of the three platforms, rejecting only four out of eight of our ads. TikTok told us it rejected our ads because they contained political content. However, its detection system appears to be ineffective - while it rejected all ads that mentioned a candidate by name, it allowed ads referencing the election and containing clear disinformation.

TikTok made its decision within 24 hours of the ads being submitted (although we left the ads online for a full week to ensure it had time to change its mind).

Our results show that TikTok has improved its performance since our last investigation. Ahead of the 2022 midterms, TikTok approved a whopping 90% of the ads we submitted. Ahead of the 2024 presidential election, that percentage has dropped to 50%.

This obviously still isn’t good enough, especially given the significantly increased use of TikTok in the US since 2020. Our test should have been very easy for TikTok to pass because the text we used unambiguously breached its policies.

A TikTok spokesperson confirmed that all of our ads breached their advertising policies. They said that they looked into why they accepted some of the ads and found that their machine moderation system approved them in error. They also emphasised that the ads in question were never published, at which point they “may” have undergone additional stages of review. TikTok also said that they would use our findings to help detect similar violative ads in the future, and stressed that their ad review processes have multiple layers (including machine and human moderation strategies) and that they are constantly improving their policy enforcement systems.

Facebook

Following the storm on the US Capitol in January 2021, Meta (Facebook’s parent company) announced that it will seek to reduce the amount of political content to which its users are exposed. With the closure of Crowdtangle, a tool used by researchers to track viral content on Meta platforms, it has also become harder for third parties to understand how political content circulates.

Ahead of this election, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg has further disengaged from politics – reportedly delegating weekly meetings on election issues to Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs, disbanding the election integrity team, and reducing the number of full-time employees working on the issue.

Again, we wanted to put to the test how these changes are playing out ahead of polling day. We created an account and posted the ads from within the US. We didn't go through Facebook’s “ad authorizations” process, which all advertisers are supposed complete if they want to run ads about elections or politics.

All ads on Facebook must comply with Meta’s policies, which prohibit misinformation about the dates, locations, times and methods for voting, about who can vote and qualifications for voting, and about whether a candidate is running or not. Facebook rejected seven out of eight of the ads submitted, approving just one ad that claimed that only people with a valid driving licence can vote. This is false election information, as only a minority of states require photo ID, and those that do, do not prescribe that it must be a driving licence.

Facebook therefore appears to have improved its moderation systems in the US since our previous investigations in 2022. Back then they accepted 20% or 30% of the election disinformation ads we submitted (in two tests in English).

However, this still isn’t good enough. Again, our test should have been easy for Facebook to pass because the text we used unambiguously breached its policies. In real life, disinformation is rarely as clear as this.

In addition, while Facebook has improved its performance in the US, its inability to detect similar disinformation in other important elections – such as in Brazil, where a previous Global Witness investigation found 100% of ads containing disinformation were accepted – shows that there are still significant gaps in international enforcement of its policies. After we informed Meta of our findings in the Brazilian investigation, we re-tested their ability to detect the exact same election disinformation in Brazil for a second time. The results showed that their processes had improved somewhat, but they still approved half of the ads for publication.

We contacted Meta to give them the opportunity to comment on our findings, but they did not respond before publication.

YouTube

Last year, YouTube made headlines with its decision to stop deleting false claims of election fraud in the 2020 US presidential election. Ahead of this election, the company announced that it would ‘remove’ content violating its community guidelines, including those on election misinformation, ‘raise’ high quality election news and ‘reduce’ the spread of harmful misinformation.

Like with the other platforms, we placed the ads via a US account and didn’t go through Google’s “ad authorizations” process.

Again, we left the ads online for a week to ensure the platform had enough time to assess them. YouTube rejected half of our ads and notified us that our entire account was paused until we provided further verification (such as a driver’s licence or passport).

We were unable to test whether YouTube would have accepted or rejected our ads had we gone through their identification verification process. Only one out of the eight ads we submitted was disapproved because of “unreliable claims” as well as references to the election, suggesting that had we provided identification, the remainder may have been approved, despite containing disinformation.

And again, while YouTube managed to flag these ads before they were disseminated in the US, its inability to detect similar disinformation in other important elections – such as in India, where we found that 100% of ads containing disinformation were accepted – shows that there are still significant gaps in international enforcement of its policies.

A Google spokesperson said that their ad review processes have multiple layers and that they are constantly improving their policy enforcement systems.

What needs to change

Some of the platforms’ systems are clearly working better than others.

While YouTube’s system was able to recognise and flag that our account was attempting to post ads on the election, its ability to recognise and flag the disinformation in our ads is less clear. YouTube therefore needs to check that its integrity measures are working properly and ensure that they are robustly applied in all elections around the world, to protect users globally.

Facebook’s moderation systems appear to have improved in the past two years. But its results still aren’t good enough, as it should have been easy for its systems to detect our disinformation, which clearly violated its policies. Meta should therefore bolster its systems in the US ahead of the presidential election, and (like YouTube) commit to giving the same level of protection to users outside of the US.

TikTok also appears to have improved its ability to detect and block disinformation since the midterms, however it continues to fail to adequately enforce its policies. By approving ads containing election disinformation for publication, despite having had notice of the flaws in its moderation systems for years, TikTok is failing to protect democracy in the US and abroad.

All three platforms must:

- Increase the content moderation capabilities and integrity systems deployed to mitigate risk before, during and after elections globally, not just in the US.

- Properly resource content moderation in all the countries in which they operate around the world, including providing paying content moderators a fair wage, allowing them to unionize and providing psychological support.

- Routinely assess, mitigate and publish the risks that their services impact on people’s human rights and other societal level harms in all countries in which they operate.

- Publish information on what steps they’ve taken in each country and for each language to ensure election integrity.

- Include full details of all ads (including intended target audience, actual audience, ad spend, and ad buyer) in their ad libraries.

- Allow verified independent third-party auditing so that they can be held accountable for what they say they are doing in all countries in which they operate.

- Publish comprehensive and detailed pre-election risk assessments for the US 2024 election.

In addition, we call on Meta to:

- Urgently increase its content moderation capabilities and integrity systems deployed to mitigate risk before, during and after the upcoming US presidential election, as a small amount of disinformation is still slipping through the cracks.

- Strengthen its ad account verification process to better identify accounts posting content that undermines election integrity.

We also call on TikTok to:

- Urgently increase the content moderation capabilities and integrity systems deployed to mitigate risk before, during and after the upcoming US presidential election.

- Immediately improve the systems and processes used to identify whether information submitted in ads to the platform is political in nature, or breaches other existing rules on the platform.

Researchers interested in knowing the exact wording of the political ad examples we used are welcome to request this by writing to [email protected].