Introduction

Land and environmental defenders risk their lives advocating for their communities’ rights against destructive industries. Often, they serve as the planet’s last line of defence, sounding the alarm about existential threats to humanity.

Their efforts frequently expose them to dangers to their safety and wellbeing. Every year, Global Witness documents these harms. In our 2024 report, we found that 196 people were murdered for defending their land and homes. Many more were abducted, criminalised and silenced by threats.

Defenders often rely on digital platforms to organise, share information and campaign. In recent years, these online spaces have become many defenders’ main channels for communication with key audiences, and are frequently relied upon for community organising. However, we now know that they suffer significant harms in these online spaces, from trolling, to doxxing, to cyberattacks.

An Indigenous activist photographs another community member after a protest march for Indigenous land rights in Brazil. Land and environmental defenders often rely on digital platforms to spread awareness about their campaigns. Mario Tama / Getty Images

Global Witness conducted a global survey – the first of its kind – to understand defenders’ experiences online. We found that online abuse is very common among defenders who responded to the survey, and frequently translates into offline harm, including harassment, violence and arrests.

This not only hurts defenders’ wellbeing but also has a chilling effect on the climate movement, with many defenders reporting a loss of productivity and, in one case, even ending all their activism due to the abuse.

Our survey shows the challenges defenders face on social media.

The situation is so dire that 91% of the defenders who responded to our survey said that they believe digital platforms should do more to keep them and their communities safe.

It doesn’t need to be this way. Social media companies’ business models prioritise profit over user safety. They can and must do more to help protect these individuals by properly investing in algorithmic transparency, content moderation, and safety and integrity resourcing.

Improving these measures will not only keep defenders safe online but will also benefit all users everywhere.

An Indigenous person documents the Acampamento Terra Livre (Free Land Camp) on a smartphone in Brasília, Brazil. Cícero Pedrosa Neto / Global Witness

A note on sampling: Surveying land and environmental defenders

Land and environmental defenders are a difficult group to reach en masse. Many such individuals have very real and immediate security concerns that require them to be highly careful about how they discuss their activism. No professional survey company has a panel of defenders available for polling.

We therefore had to manually contact defenders’ organisations by a variety of means and do our best to ensure that we had as many people as possible from as many different places respond to our survey.

We acknowledge that our survey sample is therefore not representative of all defenders and, given the nature of the survey, we have not sought to verify the accuracy of their statements.

This report is the first of its kind focusing specifically on the digital threats faced by land and environmental defenders, and the role that social media platforms play in this. We have built on our existing networks to reach hundreds of defenders globally.

This report is a crucial effort to uncover the nature of online harm faced by those on the frontlines of the climate movement and another puzzle piece in understanding what it means to stand in the way of climate breakdown.

These shocking and previously untold stories must prompt real action from social media platforms, who have often failed to act on reports of abuse.

How online abuse of land and environmental defenders harms climate action

Widespread online attacks

Many land and environmental defenders experience abuse

92% of the land and environmental defenders who responded to our survey say that they have experienced some form of online abuse or harassment as a result of their work.

The online harms that these defenders report being subjected to range from public attacks on social media, to doxxing, to cyberattacks.

Doxxing

Doxxing (short for dropping docs) is the act of publicly revealing someone’s private or personally identifiable information without their consent, typically with malicious intent. This information can include real names, addresses, phone numbers, workplace details, financial information and even family members’ details.

Doxxing can be used as a form of harassment and intimidation of defenders, and it can lead to serious consequences like stalking, identity theft, swatting (making a false emergency call to send police to someone’s home) or physical harm. It is generally considered unethical and is illegal in many jurisdictions.

Cyberattacks

Cyberattacks are malicious attempts to disrupt, damage, or gain unauthorised access to computer systems, networks, or data. These attacks can take many forms, including:

- Phishing (tricking someone into giving up sensitive information)

- Malware (malicious software like viruses or spyware)

- Hacking and data breaches (gaining unauthorised access to steal, alter or destroy information)

The impact of this abuse is significant, with high numbers of defenders reporting feelings of fear and anxiety for themselves and their communities. Almost two-thirds of the defenders who responded to our question on the impact of the abuse they suffered say that they have feared for their safety and almost half report a loss of productivity.

This means that there is a real risk that this online abuse is impacting defenders’ campaigning, which impedes progress on climate action and solutions.

Something clearly needs to change, and the platforms on which a lot of this abuse occurs must bear some of the responsibility.

When we dig a little deeper into the data from the survey responses, some disturbing trends emerge.

Activists from Extinction Rebellion march through Berlin dressed as billionaires, including Big Tech CEOs Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg. Sean Gallup / Getty Images

A Facebook problem

Defenders say they receive abuse on Facebook more than any other platform

Globally, Facebook is the platform that the highest number of defenders say they have suffered abuse on. The next most cited platforms for abuse are X and WhatsApp. Instagram is the fourth most common platform on which abuse has occurred.

Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram are all owned by Meta.

These results may in part reflect the popularity of Facebook overall as a platform (it has over 3 billion monthly active users, making it the largest social networking site globally).

Nevertheless, our survey has revealed that 82% of defenders who say they have suffered abuse online say that they have been abused on at least one of Meta’s three platforms.

Based on this data, Meta therefore holds a huge amount of responsibility when it comes to finding ways to address online harms to defenders.

The results shift slightly when comparing responses from different regions. For example, among defenders in Europe almost the same number reported experiencing abuse on X as on Facebook.

According to this survey, X therefore also holds a level of responsibility when it comes to addressing online harms to defenders.

We set out below a selection of first-hand accounts of defenders who agreed to speak with us after completing our survey. These accounts reflect the defenders’ personal experience and are given in the defenders’ own words.

Fanø, Denmark

"I have been a member of different climate activist groups in Denmark for the past five years. I have managed social media, logistics and outreach for Extinction Rebellion. As part of this, I often managed the live-streams that we did during our protests. This means I monitored the chat during the live stream on our Facebook page and answer questions.

"On more than one occasion, people have sent threats to us during these live-streams. Some of them were so concerning I took a screenshot so I could report them. They have said things like, 'If I were there, I would run you over with my car,' or, 'This is why I have a shotgun.'

Real comments made on Fanø’s Facebook livestreams including: "Just pour gasoline on them and they'll move", "You can try to stalk yourselves in front of my car when I have something to do" and "Shut up, they should have a neck shot"

"I reported these threats to Facebook, who said they would investigate, but nothing seems to have happened.

"These online attacks make me feel scared and angry. I find it so hard to understand that people can’t see that we are trying to help. I think to myself – we don’t gain anything from this, personally. We're doing this to help people and the planet. It makes me feel disillusioned.

"Facebook should stop people from sending these types of threats, but right now it seems like they are going the other way. It looks like now people are pretty much free to say anything to us, even death threats."

Laying the groundwork for offline harm

Online abuse leads to offline attacks

Another trend we can see in our survey results and follow-up interviews with defenders is that defenders who report being subjected to abuse online also report being attacked in the real world. These attacks include attacks on friends and family and physical violence.

And 75% of the respondents to our survey who say they have experienced offline harm due to them protecting their home, environment and/or climate believe that the online harm "directly" or "somewhat" contributed to the offline harm.

The proportion of defenders who feel this is even higher when we look just at the data from certain regions. 84% of defenders across Africa, Latin America and Asia who have reported experiencing offline harm due to them protecting their home, environment and/or climate say that they believe the online harm either "directly" or "somewhat" contributed to the offline harm.

Most of the interviews that we conducted also speak to this issue, with multiple defenders noting that they believe attackers use the online space to attempt to shame defenders and undermine their credibility, before launching attacks in the physical world.

Sharanya, 2025. Panos Pictures / Jonas Kako

Sharanya, India

"I have been working with NGOs in the Odisha region of India for more than 20 years. This region is very rich in bauxite, so there are many mining projects there that have been forcefully pushed by the government sometimes using military power.

"Along with a few others, I have stood alongside Indigenous communities who oppose these mining projects. These communities are fighting for their land rights, against evictions, and against harassment by the police.

"This resistance has been met by violence. We use social media to document this violence as well as the environmental destruction these projects cause.

"For example, we have posted videos on our Facebook page showing the beating of protesters, and videos showing how mining companies are releasing their wastewaters into rivers which local communities are using.

"We have been attacked online and offline for doing this. For example, when we helped stage a protest against one mining project, people took our photos and circulated them on WhatsApp, accusing us of brainwashing Indigenous communities and identifying our personal information like our home addresses.

Bulldozers operating on a bauxite mine in India’s Odisha district. IndiaPicture / Alamy Stock Photo

"After these online attacks, the police showed up at our door and accused us of being criminals and served us trespassing notices.

"Also, if we post news online on Facebook, bots and trolls will come to our page and abuse us, saying things like, 'You are outsiders, you are taking money, you are paid agents of the corporates.' They accuse us of racist things, like wanting to keep Indigenous people in the forest, wearing nothing but their underwear.

"They say we should be arrested. They have also attacked my family – accusing my father and sister of serious crimes they have not committed. They said my father had molested an employee, and my sister had siphoned off money – none of it is true. It’s always the same names, the same people commenting, as soon as we make a post.

"I have reported some of these attacks to Facebook. I recall getting a very vague response, something like, 'We are looking into your complaint,' and nothing happened after that.

Sharanya, 2025. Jonas Kako / Panos Pictures

"We ran one campaign targeting a mining company who were claiming they were helping the local community by sending Indigenous children to a private school for 'free' on the condition that their families did not attend any anti-mining protests. After this, we were trolled on Facebook for almost a year.

"We were accused online of being left-wing extremists, and our accusers eventually filed police complaints against us. They lied and said we had gone to the houses of the families who were sending their children to the school and threatened them with a gun, saying, 'We will kill you.' We have given evidence to show this is not true, but these cases are still open, years later.

"Other friends and colleagues have been treated even worse – they have been hounded out of the region. They have been threatened with rape and told they will be thrown in jail if they do not leave immediately.

Sharanya, 2025. Jonas Kako / Panos Pictures

"I think there is a relationship between what’s happening online and offline. Attackers use the online space as a means of defamation, of naming and shaming, and then use the offline space to physically threaten us and scare us, putting us under surveillance, throwing stones at our houses.

"They’re trying to silence us. These are tactics and strategies that they use to try to malign us, to break us, and put fear into us.

"This can really get to us. This can really scare us. But for the time being, we know that we are a group. We will stand by each other."

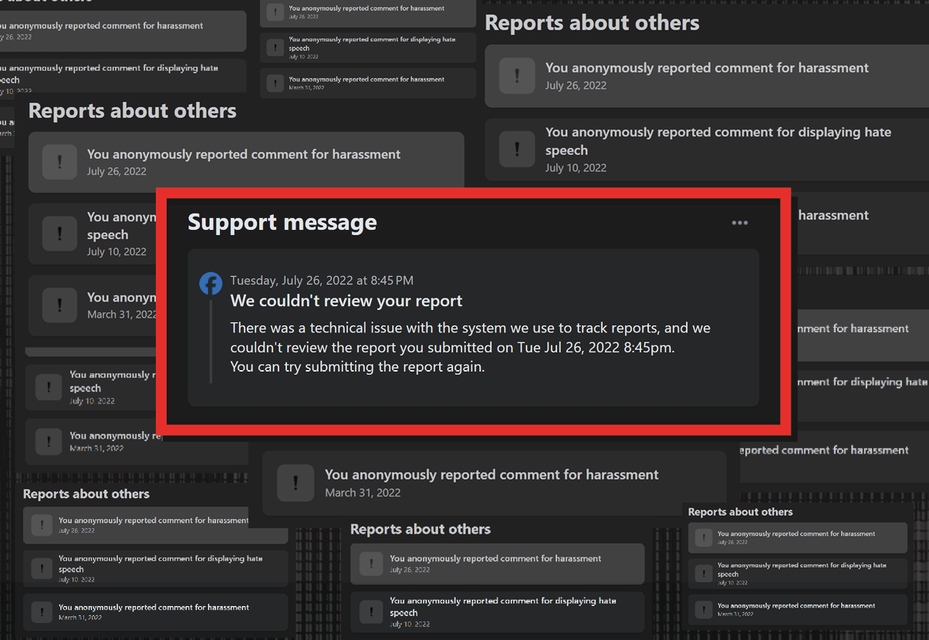

Reproduced real report made by a defender on Facebook and a platform response

Platforms failing to act

Defenders say that platforms don’t respond effectively to complaints

Our survey found that only 12% of the defenders who reported their abuse and harassment to platforms are satisfied with the response that they received from those platforms.

Almost three-quarters of the defenders say that they have reported the abuse and harassment.

Of those, two-thirds say the relevant platforms have responded to some degree.

In addition, it appears that digital platforms may be prioritising their resources towards protecting defenders in some regions over others.

The rate at which defenders have reported the harms they suffered to platforms is fairly even between different global regions.

But when we ask defenders who have made reports to the platforms how often they got responses, 18 out of 25 European respondents (72%) say that they have received at least some kind of response.

Meanwhile, only nine out of 18 African respondents (50%) say the same.

This apparent disparity in moderation resourcing echoes Global Witness’s previous findings, such as our investigations that showed that Facebook is extremely poor at detecting hate speech in Ethiopia, Kenya, South Africa and Myanmar.

This is especially concerning when we consider the nature of the threats and their impacts. Defenders in Africa and Asia report fears for personal safety at a higher rate than in other regions, and defenders in Africa report high rates of threats of physical violence and death threats.

Warom, Congo Basin

"For almost three years I have been working with environmental defenders in the Congolese basin to help defend Indigenous land rights and enforce environmental protections.

"I work as the climate and environmental communications officer in a local NGO, supporting activists who are on the frontline. I also work at a radio station with some journalists where we raise awareness of local environmental and human rights issues.

"Right now, we are campaigning against illegal deforestation in our area, and we are raising awareness about the situation surrounding the East Africa crude oil pipeline, which is a project that will affect many villages and Indigenous communities in Tanzania and Uganda.

"As part of our work, we sometimes document and expose abuses related to land grabbing and resource exploitation. Already we have seen that Indigenous lands have been grabbed, and communities have been displaced and evicted, without proper consent or compensation.

"As a result, we believe we have been subjected to surveillance, which has included phone tapping, monitoring of our online communications, and other kinds of digital spying. We think that this surveillance has been carried out by a combination of state actors and private companies.

Jealousy Mugisha refused to leave his home to make way for the EACOP pipeline without adequate compensation. He was taken to court and forced to accept compensation that he feels was too low. Jjumba Martin / Global Witness

"In addition, digital platforms have been used to spread disinformation about us. We have been falsely accused of being terrorists, and of having taken illegal payments by foreign organisations in return for our work.

"Our attackers use many different platforms to spread these lies – sometimes they use WhatsApp, other times they use YouTube, other times they text us directly or speak about us on the radio.

"Let me give you some examples. In 2022, there was a group of people who decided they wanted to ban our radio station because we were spreading information to help local communities hold on to their land title.

"They spread lies – saying we wanted to grab the land for ourselves. They issued threats on Twitter and on WhatsApp – telling me they were planning to kill me and two of my colleagues. They said they would beat us if we showed up in the community, and that they would take us to court and criminalise us.

"It was terrible because my wife could not even buy things from the market without me checking from whom she was buying.

"And in 2023, someone hacked into my WhatsApp account and used it to spread disinformation. They pretended that they were me and they said awful things, which started to turn the community against me. This was so bad, and I needed to see a psychologist to help me get through this time.

"We have reported some of the threats to the platforms. Sometimes we have had a good response – WhatsApp helped when I reported the hacking and helped me get my account back. Other times, we have not had a response.

"This online harassment has had a significant effect on us. It has discouraged us at times and has made us feel unsafe. Our work feels very dangerous, and we have feared for our lives."

A woman walks past an oil facility in Buliisa, one of the most dangerous places to be a land and environment defender in Uganda. Jjumba Martin / Global Witness

Dangerous business model

Social media platforms’ business model believed to exacerbate harm

Another theme that has emerged from our survey results is that defenders believe that the business models adopted by digital platforms are contributing to the harm caused to them.

Almost two-thirds of the defenders who report experiencing online abuse and harassment say they believe there are aspects of digital platforms that have exacerbated the abuse and harassment they suffered.

When asked to give more detail as to how this happens in practice, defenders who responded to our survey highlight the polarising nature of the algorithms employed by digital platforms, the lack of resourcing that platforms allocate towards moderation and complaints, the fact that many platforms allow trolls and bots to operate, and the monetisation techniques some platforms offer users.

Polarisation

Social media companies use algorithms that can reinforce biases and reaffirm beliefs to keep users engaged and maximise time on the platform. This can create echo chambers, deepen divisions and fuel extremism.

It can also lead to the spread of disinformation, increased hostility towards marginalised groups and even incitement to violence.

In their responses to our survey, defenders have said:

- "Polarising algorithms drive engagement."

- "The platforms only push content that polarises."

- "Outrage drives engagement."

- "Hateful comments get more traction."

- "[The algorithm] is divisive."

Lack of resourcing

When digital platforms fail to properly resource their safety and integrity teams, harmful content – such as hate speech, climate denial and death threats – goes unaddressed. This makes it difficult for defenders to operate safely online, exposing them to harassment, silencing their voices and putting their lives at risk.

Despite this, key platforms have taken the decision recently to scale down, rather than scale up, their moderation teams, with (for example) Meta announcing in early 2025 that it is ending its professional fact-checking programme in the US.

In their survey responses, defenders have also claimed that, in some instances:

- "Facebook does not censor attacks even after complaints."

- "No action is taken against harassment."

- "It’s been more than three years since we gave notice and the messages keep appearing."

Sharanya, 2025. Jonas Kako / Panos Pictures

Bots and trolls

Bots (automated accounts) and trolls (users who deliberately provoke and harass others) can be weaponised to spread disinformation, amplify hate speech and target defenders with harassment campaigns. This can lead to reputational damage, emotional distress and even real-world threats.

Defenders who responded to our survey also report that some bots and trolls operate behind anonymous profiles, allowing them to harass with impunity.

While most digital platforms have policies prohibiting inauthentic accounts and spam, they sometimes fail to effectively enforce these policies, giving abusers license to escalate harms unchecked.

In responses to our survey, defenders have asserted that:

- "Troll farms are rampant. Pages with big followings are bought and used by troll farms to reach even bigger audiences."

- "The ability of people to remain anonymous is a problem, as is the ability of people to duplicate accounts."

- "Anonymity is a problem."

- "The platforms make it easy for trolls to pollute discussions about science and climate change."

- "Anonymous accounts promote abuse online without any censorship from the service providers."

- "It is too easy to create anonymous accounts on digital platforms that foster harassment and hate."

- "The algorithm promotes 'activity', whether these are electronic bots or human beings. Anonymity is, of course, another factor since it prevents people from taking legal action."

Monetisation

Some digital platforms allow users to make money from content through ads, sponsorships and donations. This system can be exploited to fund and incentivise attacks on defenders, such as when influencers or advertisers profit from spreading hate or disinformation.

It could also discourage platforms from taking action against harmful content if it is generating revenue.

One defender from Colombia told us: "They deliberately invested in sponsored content to ensure that their false narrative reached as many people as possible, manipulating public perception and trying to destroy our reputation.

"This wasn’t just an organic post; it was a calculated smear campaign, using paid promotion to amplify lies and make them seem credible. They used social media as a weapon, ensuring their defamation was seen by thousands, all while pretending to be on the side of conservation.

"This kind of attack is not only unethical but also exposes the real intentions behind their actions: to discredit us and justify their attempt to take over our land."

Many of the interviews with defenders conducted for this report also speak to the issues of polarisation, resourcing, bots and trolls.

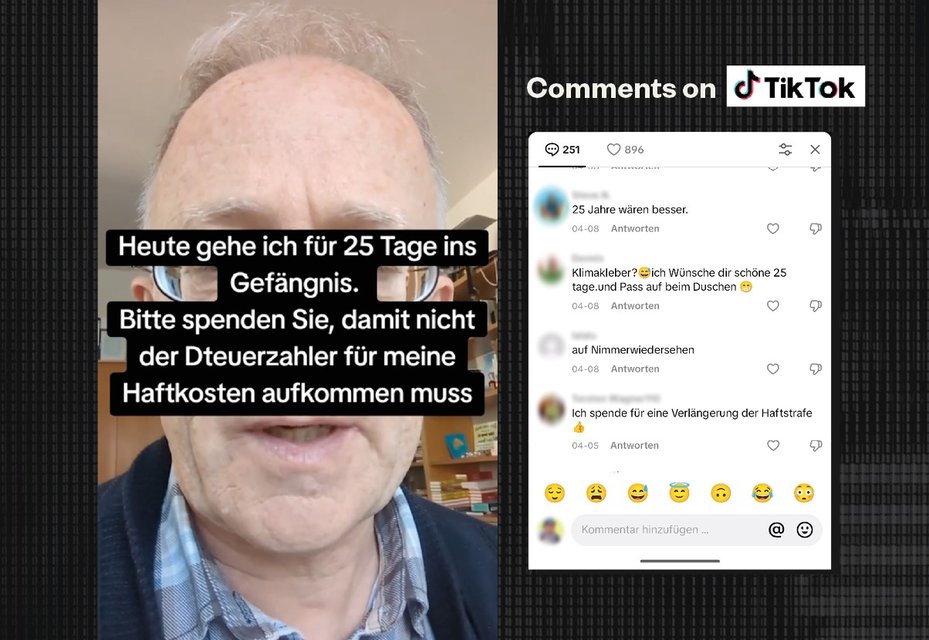

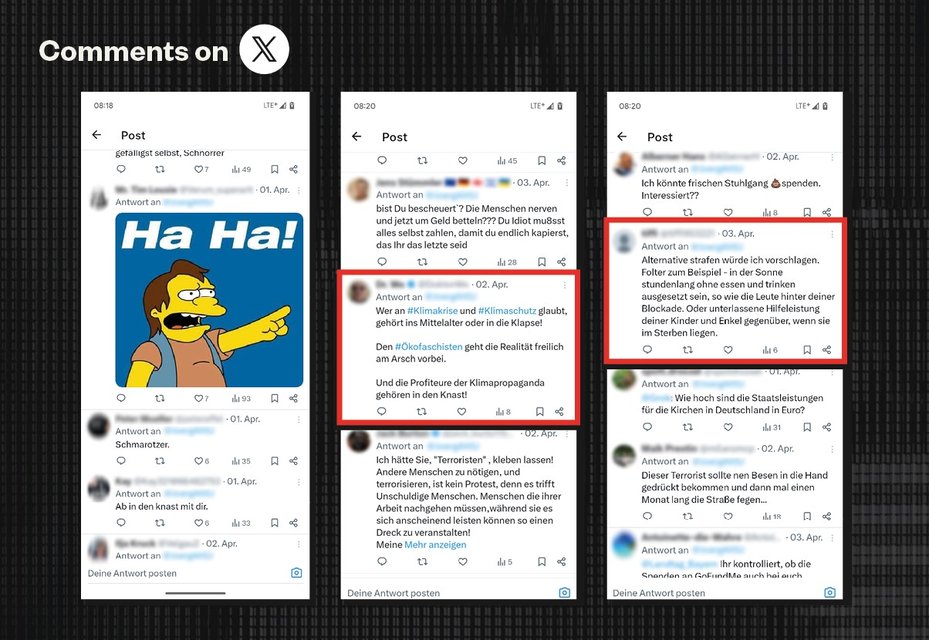

Jörg, 2022. Johanna Lohr / Global Witness

Jörg, Germany

"I am a priest with the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuits. For years I tried to help advocate for climate solutions, but I experienced so much abuse on social media that I temporarily stopped my online activism.

"I became involved in climate action back in 2021, when a group of activists went on hunger strike ahead of an election to raise awareness of the impact of climate change on younger generations.

"I then became involved in the German climate movement that draws attention to food wastage by deliberately stealing food out of the dustbin, distributing it publicly, and calling for the police to arrest the thief (who was, of course, me).

"In certain justified situations, with good reasons or narratives, I also supported some young activists who were blocking roads in Germany to symbolise the disruption climate change is causing.

Jörg on 28 October 2022 with activists from the groups Scientists Rebellion, Extinction Rebellion and Last Generation blocking the Karlsstraße in Munich to draw attention to climate policy grievances. Sipa US / Alamy Stock Photo

"Eventually I ended up with 10 legal cases against me because of this activism, and these cases were often featured heavily in the media.

"It was after this that the abuse on social media started. I was on Facebook, Instagram, Mastodon and Twitter (as it was then known) at the time, but I was not very active. After these media reports happened, my profile on social media grew.

"My follower count on X (formerly known as Twitter) went up from 500 to 13,000 immediately, and ever since it has sat around that level.

"I also joined TikTok because the younger activists asked me to do so – since TikTok is most heavily influenced by populist and extremist propaganda in support of the AfD, Germany’s most right-leaning party, and the younger activists wanted to organise a counter-public narrative.

"For me, the discourse on Facebook, Instagram and Mastodon has been quite civilised. But on X and TikTok, it has been terrible.

"Lots of fake-looking accounts on X and TikTok have accused me of the worst things – from doubting my intelligence and my sincerity, to suggesting that because I’m a Catholic priest, I am only supporting these young climate activists for some degenerate sexual reason. They have even threatened to beat me and kill me.

"I have also had anonymous messages that say things like, 'Next time I see you on the road, I’m using my car to run over you.'

"I reported some of these threats to the platforms, but they just said things like, 'We are investigating, why don’t you block them?' I occasionally do block and mute these accounts, but it does not fix the problem.

"I have not gone to the police, because what can they really do? These accounts are all fake or anonymous. Anonymous threats also make it difficult to report them to the police. Given the absence of any evidence of who is behind fake accounts, it is also near to impossible for the police to investigate such offences. They file a complaint and immediately close the file.

"Most other activists I stand alongside have received similar threats, and they continue without allowing themselves to be intimidated. I tried to do the same for years. But in 2023 it became too much for me. I could not afford all the legal fees, and I also did not want to live in fear anymore. So I had to pause my activism.

"Insults continue, however, since I am still featured in the media for legal prosecution or, recently, for going to prison.

Jörg, 2022. Johanna Lohr / Global Witness

"I think social media is a big part of the problem. It's so easy to be hateful on there.

"I bet if the people who are threatening to kill me on social media met me tomorrow in the street, we would have a civilised conversation, because we would look in each other’s eyes. But if you just look in your computer screen and you feel powerful or angry, then things happen online which in normal life would not happen.

"At the same time, it’s clear that this kind of hatred on social media also lowers the threshold of evil things in public. So sometimes I'm afraid that I will actually be beaten up one day.

"I think the platforms should not allow people to have so many different accounts. It opens the door for everybody to create anonymous accounts and send all this hate.

"For some activities there are strict procedures of checking the identity of the user, e.g. for TikTok Live. This should be extended to all who want to open an account.

"I think that the situation on social media would improve dramatically if everyone had verified accounts, and if we knew that we were dealing with real people using their real identities, and not just a troll or bot or whoever."

Vlad, 2025. Ioana Moldovan / Global Witness

Vlad, Romania

"I am an activist who works as part of an NGO that’s fighting for a just energy transition. We are trying to help end fossil fuel-based energy production in Romania and make sure that any new projects (like renewables) consider nature, biodiversity, and the people most affected by the transition.

"We use social media to bring the people’s attention to these issues and to share reports we have published. We have two channels on Facebook and Instagram that we use for this.

"We experience online harassment on every channel. The attacks we get on Facebook are a lot worse and more aggressive than the ones we get on Instagram. We have also been attacked in traditional media, like on TV news programs.

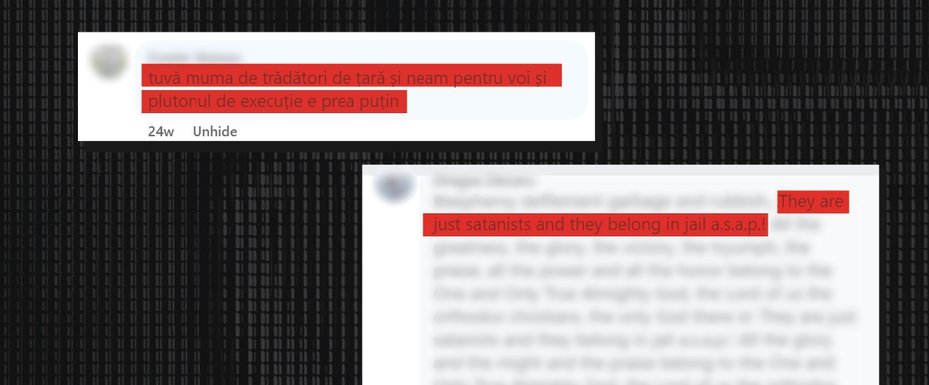

Real comments made on Facebook calling the group "traitors to the country" and saying "for you the firing squad is too little"

"The attacks on us seem to be encouraged by Facebook influencers. One of these influencers used their popular Facebook channel to identify us after we opposed a hydropower project. They shared our names and told their audience to write to us and 'give us their opinions.'

"After this we received so much hate. Some of our online attackers found our personal Facebook accounts and sent us direct messages there, including to the girlfriend of one of our team members who had nothing to do with our activism. They said things like we should be thrown in jail, or we should be thrown out of the country, because we have committed treason.

"Another influencer did a similar thing, sharing our details on his Facebook channel. He didn’t say anything directly – just reposted media articles about us that said that activists like us need to face court.

"I think these influencers are trying to be a bit clever, to try and get around the platforms’ policies, and put it on somebody else to send us the abuse.

Vlad, 2025. Ioana Moldovan / Global Witness

"We have seen this abuse move from the online to the offline space – with employees of mining companies being used as pawns to stage a protest against us, saying similar things – that we have committed treason and must be jailed or banned.

"This protest was covered by the media, and they shared our names and faces on TV. They took a photo of one of our female colleagues from her private Facebook account and shared it onscreen, causing her anxiety about possible personal attacks.

"As a result of all of this, we made a complaint to our national media coverage agency, but this led to nothing. Then we made a complaint to the UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders, and he launched an investigation and wrote to the Ministry of Environment. Unfortunately, the answers from the Ministry were not very satisfying.

"We have also reported the comments to Facebook but have not received any meaningful answer.

"I would like to see social media platforms like Facebook take these comments seriously and act on them when they are reported."

Online accusations of criminality

Defenders are commonly accused of criminality

Perhaps unsurprisingly, defenders report being most attacked for their work (i.e. their writing and reporting). Attackers also commonly reference the defenders’ jobs and their credibility.

A worrying pattern indicated by the data, however, is that perpetrators sometimes target defenders’ political affiliations and reference the legality of their actions when abusing them online.

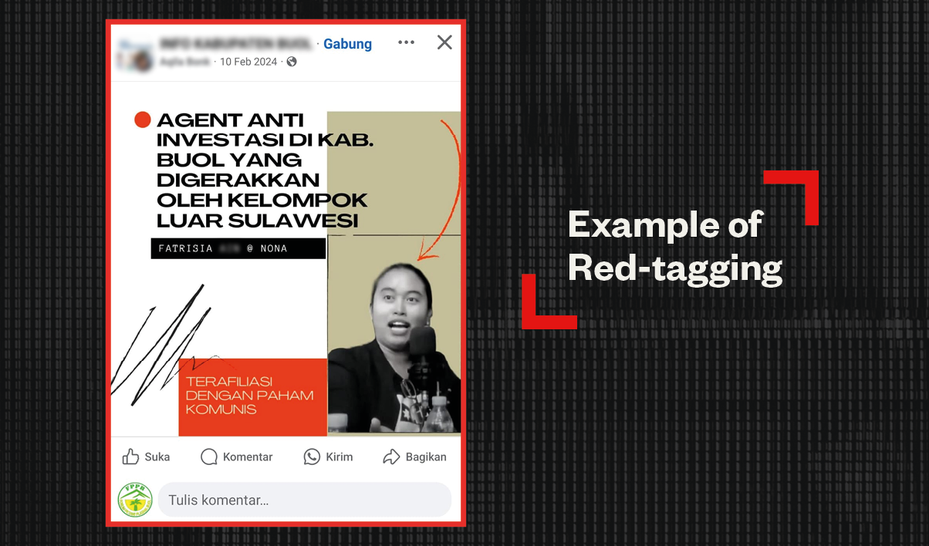

Accusations relating to political affiliations

This practice can see defenders unjustly accused of having subversive political beliefs regardless of their true political affiliations, such as accusations of being a communist in countries with strong anti-communist sentiment (often known as "red-tagging").

In our survey results, defenders from Asia and Europe report the highest rates of having been targeted based on political affiliation.

Nine out of 10 defenders from the Philippines who responded to this question, and four out of five respondents from Denmark, say they have been targeted on this basis.

Jonila Castro, along with fellow activist Jhed Tamano, reportedly experienced red-tagging after they worked with coastal communities resisting land reclamation in Manila Bay. Raffy Lerma / Global Witness

Criminalisation

This practice sees defenders unjustly accused of behaving illegally regardless of the actual legality of their actions, such as labelling climate protesters as terrorists or threats to national security.

Both of these practices are employed as tactics to intimidate, defame and vilify legitimate activists for their work. They not only undermine defenders’ credibility, but also expose them to violence and social stigma, dividing them from the communities they live and work within.

By undermining defenders online, those in power are more easily able to then criminalise them offline, by creating a drumbeat of allegations and suspicion that can be amplified elsewhere and drawn on in criminal proceedings.

By framing defenders’ resistance as illegal, those in power can also attempt to justify land grabs, deforestation and resource exploitation while diverting attention from the real environmental and human rights violations taking place.

Protestors speak out against the disproportionate sentencing of three Just Stop Oil activists in London, UK, 2024. Global Witness

In our survey results, 35% of the defenders who experienced online abuse and harassment said that they had received offline threats of criminalisation, and 30% said they had actually been criminalised (e.g. arrested).

Defenders from Europe report very high rates of having been targeted with accusations relating to the legality of their actions.

Accusations of political extremism and criminalisation also emerge as themes in almost all the interviews with defenders conducted for this report, with some of these defenders report seeing their online attacks result in real life arrests and judicial proceedings.

Fatrisia, 2025. Sarjan Lahay / Global Witness

Fatrisia, Indonesia

"I live on the island of Sulawesi, where there are many rural farming communities whose lands have been seized through Indonesia’s palm oil plantation partnership programme. I am part of a local collective of women who are fighting to regain the rights to our land.

"Over the past three years, we have been attacked in our homes, on the way to assisted villages, at protests, and online.

"Facebook is very popular in our area, and it is what we must use for our advocacy. I have been repeatedly attacked on this platform. Unidentified attackers have taken photos from my personal Instagram account and posted them on Facebook group pages with lots of followers.

Real Facebook post red-tagging Fatrisia. It’s presented as a local news update calling Fatrisia a communist who is working for groups outside the region trying to stop investment

"These posts were filled with hate speech and lies about me. They accused me of being a communist, which is a very serious allegation in Indonesia. They accused me of conspiring to defraud the farmers and called for my immediate arrest by the police.

"They also said I am rumoured to be having an affair with a fellow activist, which is another serious allegation in Indonesia, as I am a young, unmarried woman. I think they are trying to shame me and take away my credibility.

"I have also been attacked on Instagram. Sometimes we speak live on Instagram when staging a protest. Several times we have received insults through comments from certain parties who watched it.

"I asked Meta, who own Facebook and Instagram, to take down the posts, but they have not done it.

Fatrisia and community members, 2025. Sarjan Lahay / Global Witness

"I have been attacked offline as well. Along with others, I have been sexually harassed and assaulted when attending protests.

"These attacks have had a big effect on me and the other women in my collective. Our organisation does not have the financial resources to pay for psychological counselling. We also need to work by gardening, selling foods and other part-time jobs to support our personal and family finances in between organising and advocacy efforts. Our physical and mental burden is very, very heavy.

"We feel exhausted because we must explain over and over again to relatives and friends who find out about the attacks on Facebook and Instagram. And they’re either worried about us or they worry that it’s true.

"The hardest part for me was when relatives came to my family’s house and told my parents about the attacks on Instagram and Facebook. My parents were so worried and begged me to stop. That was so hard because I’m not just worrying about protecting myself, I’m worried about protecting my parents, too.

"I would like to see Meta change its policies so that the impact of these attacks is recognised. And I’d like for the people who attack me online not to be able to remain anonymous."

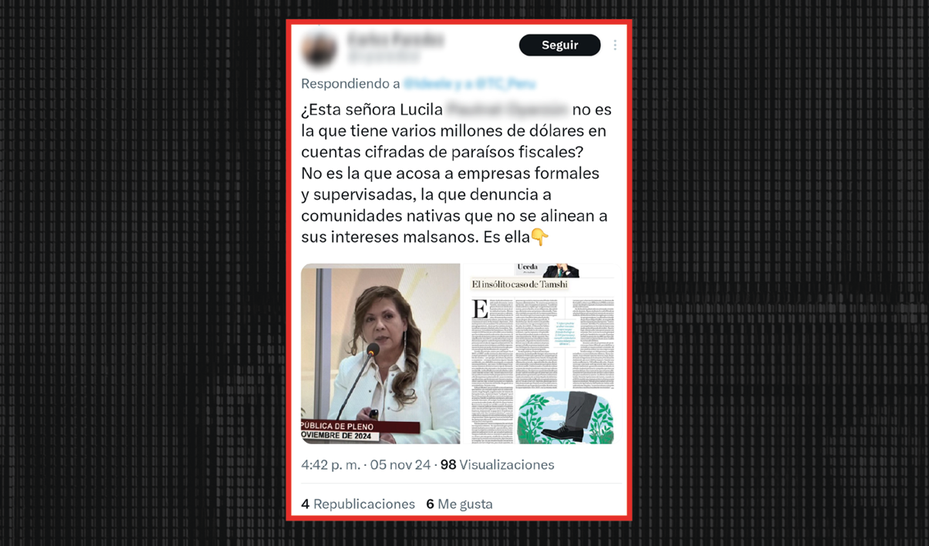

Lucilia, 2025. Angela Ponce / Global Witness

Lucilia, Peru

"I am a forestry engineer and for more than 20 years I have been fighting alongside Indigenous leaders against illegal logging, deforestation, illegal mining and environmental crimes in the Peruvian Amazon.

"I am fighting to protect tropical forests and their extraordinary biodiversity from both national and international agribusiness companies that I believe engage in violent land trafficking and deforestation in Peru. In response, I believe these companies have funded aggressive smear campaigns against me online.

"For the past five years, I’ve faced relentless harassment – online, in traditional media and through legal proceedings. The backlash has been so severe that Peru’s Ministry of Justice and Human Rights granted me protective measures as an environmental defender. I was the first person in Peru to receive such an order under the state’s Mechanism for the Protection of Environmental Defenders.

"Unfortunately, over the last few months, these measures have become purely symbolic –in practice, they’ve failed to stop the threats against me and my family.

Real Facebook post suggesting that Lucilia is money laundering and denouncing Indigenous communities "that don’t align with her unhealthy interests"

"I’ve faced intense pressure and abuse from political and media actors who I believe are backed by corporate interests. In my view, their actions – including surveillance and online harassment – are intended to intimidate me and disrupt our investigations into environmental abuse.

"I’ve seen false allegations appear in certain media outlets, accusing me of embezzling funds and hiding money offshore. These claims have circulated widely on Facebook, TikTok, YouTube and X, even though both national and international authorities have issued statements debunking them.

"I’ve asked the platforms to remove these accusations, but they’ve refused, claiming they can’t act until the related court cases are resolved.

Lucilia, 2025. Angela Ponce / Global Witness

"I’m now under investigation for money laundering – a case with no legal or factual basis. I’m fighting these fabricated charges, but the legal battle has drained me financially. Only 40% of my defence costs have been covered by three supporting organisations; the rest has come from my own pocket, severely affecting my livelihood amid the ongoing harassment.

"I know how tough this fight is. Some of the Indigenous leaders I’ve stood with have been killed. But despite everything, they haven’t broken me. They won’t intimidate us. One day, I’ll have to reckon with the emotional toll of all this – but for now, I’m standing my ground."

Gender and sex a key theme

Women defenders report threats targeting their gender

Another theme that emerged from the interviews conducted for this report is that women are being targeted online, often using sexualised threats, and are being silenced in the fight for our climate.

Many women defenders in the survey describe gendered online abuse, including rape threats and sexual harassment. Sarjan Lahay / Global Witness

Many of the women defenders who agreed to be interviewed for this report described online attacks of a sexual nature, including rape threats and false allegations of sexual relationships with fellow activists.

Almost a quarter of the defenders who reported receiving online abuse say they are attacked on the basis of their sex, and almost a fifth say they are attacked on the basis of their gender identity.

In a number of cases, defenders who responded to our survey say that these online threats translated into offline harms, such as sexual harassment, threats of sexual violence, and assault.

These findings support numerous investigations by others (including the United Nations) that show that women are more likely to be targeted for online attacks, including various forms of abuse and harassment, compared to men. This includes sexual and gendered abuse, which is often more severe and psychologically damaging for women.

Women are also more likely to experience the negative impacts of online abuse, such as fear for their safety and retreating from online spaces.

They also support previous Global Witness investigations which show that social media platforms approved adverts containing violent hate speech targeting women and the LGBTQ+ community.

And they support the findings of Global Witness’s 2023 investigation into online attacks of climate scientists, which revealed that women scientists were targeted more on their appearance and threatened with violence.

Disha, 2023. Julien de Rose / AFP via Getty Images

Disha, India

“My name is Disha. I’m a climate justice activist and one of the founding members of Fridays For Future India. My work has been focused on land and forest rights, and the intersection with digital rights, mainly because we couldn’t be on the ground during the pandemic so we had to campaign online.

“During the lockdown in 2020, we were organising against the draft Environmental Impact Assessment – a bill that would make it easier to get clearances for infrastructure projects, removing the democratic process where people impacted could have a say.

"We ran a digital campaign, including Twitter storms, promoting the Ministry’s email consultation, giving the public the chance to comment. All the movements collectively mobilised around 2 million people to send emails and the bill didn’t get passed because of public pressure.

"The response was a huge crackdown. The government blocked our website and claimed we were a threat to India’s peace and sovereignty. They informed the Delhi police and used India’s anti-terror law against us, even though all we were doing was encouraging public participation.

"No one was arrested then thanks to the support of Internet Freedom Foundation, who wrote a response, but there was always this threat hanging over us.

“I remember criticising a spiritual leader once. His followers were furious. They started tagging right-wing legal groups under my tweets. One of my tweets had over 300 comments. I reduced my posting after that because I could see how quickly it can turn into a legal case, or something that escalates offline.

Protestors demand the release of Indian climate activist Disha Ravi. Aijaz Rahi / AP Photo

“A lot of the abuse is gendered. It’s not just about my work – they go after me as a woman. They question my intelligence, they call me names, they say things about my parents, about how I was raised. There are threats of sexual assault.

"For women, it always comes back to your appearance, your character, your family. Then there’s just absolute hatred where they dismiss what you’re saying and they’re actively against the work you do. It can be quite scary.

“It made us really cautious about what we were sharing online. We don’t share updates in real time because we don’t want to draw attention that could derail what we’re doing. When we speak about Palestine, which is something we’ve been vocal about on social media, we do get a lot of hate.

"I still don’t update my LinkedIn because I’m so worried about being doxed. It feels like if I share anything about myself, someone will try to use it against me or find me. It’s so easy – if someone knows your full name, they can look you up, find where you work, find your address.

“In my experience, Twitter is the absolute worst platform for this. I find the abuse there is on a different scale – it’s very easy for something controversial to get really viral and reach people outside your bubble. I don’t think Instagram has the same capacity for trolls and we’re not very active on Facebook.

"I mostly just block people on Twitter because I was scared. There were times when I reported them to Twitter, but I don’t remember getting a positive outcome. At some point I stopped reporting and just mass blocked them.

“I do think platforms need to take this seriously. Yes, free speech is important. But that doesn’t mean people should be allowed to threaten violence or run coordinated harassment campaigns.”

Annika, 2025. Unwisemonkeys / Global Witness

Annika, Denmark

"I’ve been involved in grassroots environmental activism in Denmark since 2019. In that time, I have engaged in many different climate activist groups, and I have documented the experiences my fellow activists have been having online and offline.

"I am sad to say that I have seen a real increase in the repression of climate activists and the intensity of online attacks in the past five or six years.

"From what I’ve seen, female activists have suffered the most abuse online. The common scenario I see is that a female spokesperson appears in traditional media speaking about a climate issue. The next day, her inbox will be flooded with hate mail, sometimes even death threats, and rape threats.

"It’s quite easy for people to use a person’s name to find their social media profile – whether it is public or not. From what I can tell, almost all of these threats come from men.

"I have seen activists being attacked across all platforms – Twitter (or X, as it’s now known), Facebook, and Instagram. I have seen screenshots of the abuse.

"Denmark, like other Scandinavian countries, has a tradition of being an open society where everyone can look up each other’s addresses and phone numbers. But many climate groups’ spokespeople are choosing to hide their addresses and phone numbers right now out of safety concerns and most spokespeople are women.

![Real comments made on women defender’s Facebook pages including "Looks like someone who could use some meat. Looks a little starved [sexual connotation]", "She is stupid to listen to such a madman" and "Screw crazy woman person [derogatory Danish term]"](https://gw.hacdn.io/media/images/DT_Defenders_screenshots_AW11.width-929.png)

Real comments on women defender’s Facebook pages incl ‘Looks like someone who could use some meat. Looks a little starved [sexual connotation]’ ‘She is stupid to listen to such a madman’ ‘Screw crazy woman person [derogatory in Danish]’ & 'Shut up, bitch'

"I have worked in groups that have staged climate protests that block roads and stand in the way of traffic. In response to this, we have seen political leaders say things like they would understand if people drove over activists with their cars.

"This sort of speech in the media and online legitimises violence in real life. The discourse we see online and in the tabloid media opens up the space for offline violence.

"All of this abuse is having a chilling effect on the climate movement in Denmark, because people are afraid. And it’s much harder to be effective as an activist, because activists need attention in traditional media to get their message of climate action across. But as soon as they appear in the media, they get attacked online. It’s a very difficult choice to make.

"In theory, activists can try to block the abusive content. But that’s very hard in practice. People have reported some of the abuse, but I can’t recall that working anytime.

Annika, 2025. Unwisemonkeys / Global Witness

"I think this is happening because, to some people, the online space feels lawless. People seem to feel that the online world is free from rules or regulations, and free from morality and social etiquette. People say things online that they’d never say to someone’s face.

"And this is having a huge effect on climate activism because everyone is online so much and seeing all this abuse. And in turn, I think that’s where we see the chilling effect bleed into real life.

"The tech companies should be responsible for limiting hate speech and harassment, but we all know politically that is not where it’s going. We also need the algorithms to change so they stop promoting polarising content. And I’d like to see content moderators being treated fairly – so being paid a fair wage, and in decent working conditions."

Annika, 2025. Unwisemonkeys / Global Witness

Conclusion

Attacks on land and environmental defenders hurt us all

If defenders cannot operate safely online, we lose access to their important voices in the fight for our planet.

Our survey and the interviews with defenders conducted for this report demonstrate that online abuse has had a chilling effect on the climate movement. Defenders reported that they have lost productivity due to the abuse, and even retreating from their activism due to the abuse.

It is imperative that any social media company claiming to care for the climate take immediate action to safeguard those most at risk, including defenders. At their best, these online spaces can have a democratising effect but only if they prioritise inclusivity and safety to ensure a healthy debate.

Reforms and recommendations

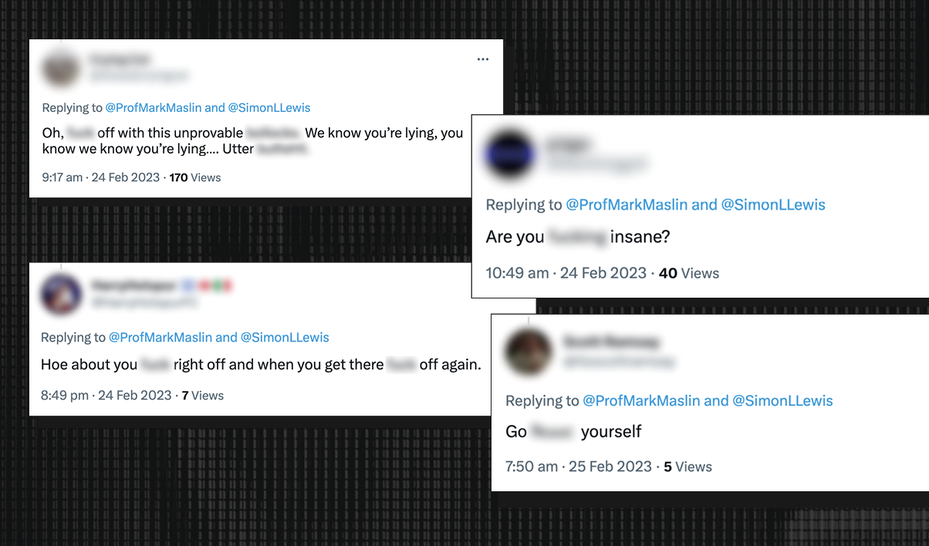

Our survey provides an insight into the challenges defenders face on social media. Meta owns three out of four of the platforms where the most defenders reported being attacked (Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram), with X being the other.

This is not the first time that these platforms have had notice of these issues. A 2023 Global Witness survey of 468 climate scientists revealed that 39% had experienced online harassment related to their work, with this figure rising to 49% among more established scientists.

That previous survey found that the abuse of climate scientists primarily occurred on Twitter (as X was formerly known) and Facebook.

Online abuse of climate scientists surfaced during a previous investigation

And in November 2024, around the time of the US election, a Global Witness investigation found that Meta’s moderation systems were struggling to keep pace with hate speech, allowing abuse to flourish on US Senate candidates’ pages.

However, instead of upping their game to address these harms, these platforms have done quite the opposite. Since we published our previous survey, both X and Meta have implemented significant changes that may have contributed towards reduced user protection.

In 2023, X discontinued its feature for reporting misleading information, and the previous year it disbanded its Trust and Safety Council, which had been addressing issues such as hate speech and harassment since 2016.

X claims efforts to combat misinformation were replaced by Community Notes, a crowd-sourced system where contributors provide context and fact-check posts. However, recent research has suggested that the system may not be equipped to address harmful narratives and disinformation, like the examples surfaced in our report.

In 2024, X also announced that they had hired over 100 in-house content moderators, but this is considerably smaller than the 1,500 moderators used by the company before changes under Musk.

In 2023, the European Commission opened formal proceedings to assess whether X may have breached the Digital Services Act in areas linked to risk management, content moderation, dark patterns, advertising transparency and data access for researchers.

Although the European Commission’s preliminary findings focus upon X’s alleged failures on advertising transparency and public data access, the European Commission found that there is evidence of motivated malicious actors abusing X’s "verified account" system to deceive users. If proven, these charges can result in huge fines.

Meta announced in January 2025 that it would end its third-party fact-checking programme in the US, replacing it with a Community Notes model similar to that of X, as well as watering down its policies on hate speech. This shift, framed as an effort to promote free speech, has raised concerns about the spread of misinformation and hate speech.

Like X, Meta also encourages users to block, mute and/or report abusive accounts, though our survey indicates that reported abuse is often not effectively addressed.

These collective changes by both platforms have heightened concerns about their susceptibility to abuse and the proliferation of harmful content.

In March 2025, Global Witness contributed to an analysis by civil society which found that social media platforms like Meta and X had failed to adequately assess and address the actual and foreseeable risks posed by their services, despite EU rules requiring them to do so.

Sharanya, 2025. Jonas Kako / Panos Pictures

A business model that drives abuse

Social media companies make most of their profit from advertising, and the product that they sell to advertisers is the attention of their users. To capture this attention for as long as possible, these companies often experiment with showing users different types of content and closely surveilling what keeps them engaged.

As such, platforms’ algorithms often promote manipulative disinformation or rage bait.

By boosting such content, these platforms help give rise to dangerous falsehoods, societal division and even violence. It also makes it harder for users to distinguish fact from fiction and advance collective action on the climate emergency.

It’s been clear for a while now that social media companies like X and Meta need to address this by allowing independent evaluations of their algorithms and committing to respecting user safety and rights.

A return to responsible content moderation?

Since their inception, the content moderation efforts of both X and Meta have been imperfect and changeable. Since the election of President Trump, however, standards have slipped even further, with both platforms doubling down on their approach, prioritising "free speech" over user safety.

As our survey shows, this approach undermines freedom of expression and other rights.

By properly resourcing their content moderation systems, digital platforms can help to reduce the amplification and spread of disinformation around critical issues like climate change, as well as reduce the circulation of incendiary or hateful content.

At the same time, investing in robust moderation processes can help address the growing problem of spam that clutters feeds and frustrates everyday users, improving the overall quality and trustworthiness of the user experience for everyone.

Platforms should provide sufficient support to moderators across the globe and the different languages used on the platform, including paying content moderators a fair wage, allowing them to unionise and providing psychological support.

They should regularly review the effectiveness of their processes, invite external input and disclose their actions and findings with users.

Resourcing is a choice. Both Meta and X have it within their power to help fix this problem. This would not only benefit users most at risk, like defenders and the climate movement overall, but it would help to improve the experience online for everyday users.

We gave Google, Meta, TikTok and X opportunity to comment on our main findings.

Meta directed us to their Safety Center and resources on bullying and harassment prevention, which include a "Hidden Words" feature which allows users to filter offensive comments and direct messages, and a "Limits" feature.

TikTok pointed us to their Community Guidelines on harassment and bullying and said that they do not allow harassing, degrading or bullying statements and behaviour. TikTok also said that between January and March 2025, 91% of the videos removed by TikTok for violating policies on harassment and bullying were removed proactively before they were reported.

The other companies declined to comment.

Methodology

We emailed our survey invitation widely to organisations, coalitions and trusted partners, posted it on our social media channels, and asked defenders to disseminate the survey as they saw fit.

When we were in a real or online environment where defenders were likely to be present (such as at an international digital rights conference), we encouraged people to complete the survey and share it with others.

We knew that we wanted to reach as broad a range of defenders as possible, which meant some defenders will have received the survey without having had any contact with or knowledge of our organisation before, or the host of the online survey, Survation.

We therefore knew there was a risk that response rates would be lower than with other surveys.

For information on the difficulties of creating a representative sample of defenders, see "A note on sampling: surveying land and environmental defenders" section.

To respond to our survey, we asked participants to self-designate as land and environment defenders (or as we defined it, anyone who considers themselves to be “someone who actively protects their home, the environment and/or the climate”).

The survey was live between 5 November 2024-18 March 2025. View the survey’s full results

Response rates to our survey varied by region. We have only reported regional findings from regions which had more than 15 responses, which in practice means that we have not reported findings from North America and Oceania. 204 defenders responded to our survey in total.

We were also able to speak to a small group of defenders directly to hear about their experiences in more detail. These interviews are included in the report as direct quotes and testimonies. Due to the nature of these accounts and the complexity of the harms, we are not always able to independently verify every claim.

We have stated all percentages from the survey to the nearest percent.

We translated the survey into French, Spanish, Portuguese, Filipino and Bahasa Indonesian.

Resource Library

Full report: Toxic platforms, broken planet

Download Resource