A whopping 90% of election disinformation ads tested were approved by TikTok

An investigation by Global Witness and the Cybersecurity for Democracy (C4D) team at NYU Tandon looked at Facebook, TikTok and YouTube's ability to detect and remove election disinformation in the run up to the US midterm elections.

The investigation revealed starkly contrasting results for the social media giants in their ability to detect and act against election misinformation.

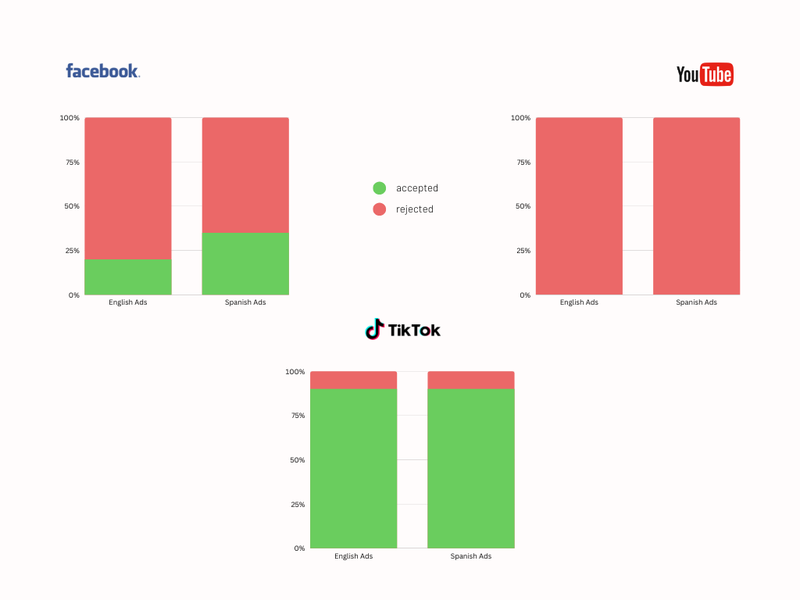

TikTok fared the worst. The platform, which does not allow political ads, approved a full 90% of the ads containing outright false and misleading election misinformation.

Facebook was only partially effective in detecting and removing the problematic election ads. Only YouTube succeeded both in detecting the ads and suspending the channel carrying them, though this is in glaring contrast to the platform's record in Brazil, where similar ads were approved.

TikTok and Facebook fail to detect election disinformation in the US

Download ResourceTesting social media platforms

Our investigation tested whether three of the most widely-used social media platforms in the US – Google’s YouTube, Meta’s Facebook, and TikTok – were able to detect election-related disinformation in ads in the run-up to the midterm elections on Tuesday 8 November.

Election disinformation dominated the 2020 US elections, particularly content that aimed to delegitimize the electoral process and result, and there are widespread fears that such content could overshadow the vote in the US again this year.

All ad content tested by Global Witness and C4D contained outright false election information (such as the wrong election date) or information designed to discredit the electoral process, therefore undermining election integrity.

The experiments were conducted using English and Spanish language content. We did not declare the ads as political and didn’t go through an identity verification process. All of the ads we submitted violate Meta, TikTok and Google’s election ad policies.

After the platforms had informed us whether the ads had been accepted, we deleted them so they weren't published. Our experimental protocols were reviewed and deemed to not be human subjects research by New York University’s Institutional Review Board, which reviews the ethics of experiments involving human research subjects.

In a similar experiment Global Witness carried out in Brazil in August, 100% of the election disinformation ads submitted were approved by Facebook, and when we re-tested ads after making Facebook aware of the problem, we found that between 20% and 50% of ads were still making it through the ads review process.

YouTube performed similarly badly, approving 100% of the disinformation ads tested in Brazil for publication in our experiment running concurrently to this one in the US.

Our findings are a stark reminder that “where there’s a will, there’s a way” – YouTube not only prevented all election disinformation ads from appearing in the US, it also banned our channel outright.

This shows the stark difference in its enforcement efforts during high-profile national elections. In the US they rejected all our disinformation ads whereas in Brazil they approved them all, despite the fact that the election disinformation was very similar and the investigations took place at the same time.

And despite problematic ads still slipping through, Meta’s Facebook showed the stark difference between its moderation efforts in the US as opposed to the rest of the world, with previous Global Witness investigations finding 100% of election disinformation ads tested in Brazil and 100% of hate speech ads tested in Myanmar, Ethiopia and Kenya making it through Facebook’s systems.

With election day in the US just weeks away, and with voting already underway in some states, TikTok and Facebook simply must get their political ad policy enforcement right – and right now.

Our investigation

We tested YouTube, TikTok, and Facebook’s ability to detect election-related disinformation ahead of the midterm elections, using examples we sourced from themes of disinformation identified by the FEC (Federal Elections Commission), CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency) and civil society.

In total we submitted 10 English language and 10 Spanish language ads to each platform – five containing false election information and five aiming to delegitimize the electoral process. We chose to target the disinformation on five “battleground” states that will have close electoral races: Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, North Carolina and Pennsylvania.

We submitted the election disinformation in the form of ads as this enables us to schedule them in the future and to remove them before they go live, while still being reviewed by the platforms and undergoing their content moderation processes.

The content clearly contained incorrect information that could stop people from voting – such as false information about when and where to vote, methods of voting (e.g. voting twice) and, importantly, delegitimized methods of voting such as voting by mail.

We used identical ads on all three platforms.

We used a dummy account to place the ads without going through the "ad authorizations" process. As well as violating their policies on election disinformation, this also violated Meta’s policies on who is allowed to place political ads.

This is a safeguard that Meta has in place to prevent foreign election interference that we were easily able to bypass. Even with verification, foreign-based accounts are not supposed to be able to post political ads in the US.

In our first test in early October, with ads posted from the UK, 30% of ads containing election disinformation in English were approved and 20% of ads containing election disinformation in Spanish were approved.

We tested the ads again two days later, this time posting ads using a different account from the US. Alarmingly, 20% of ads in English were approved and 50% of Spanish disinformation ads were approved.

There is a lack of consistency about which ads were approved and which were rejected.

Ads suggesting a change in election date were approved in both tests in English but rejected in Spanish. Two ads in Spanish – one telling people that they needed to vote twice to be sure their vote would count and another stating that only vaccinated people were allowed to vote in person – were approved in both tests.

As of publication of this report, only one dummy account has been suspended, and after the ads were deleted from the account. The other two dummy accounts we used to place the ads have not been closed by Facebook.

A Meta spokesperson said in response to our experiments that they “were based on a very small sample of ads, and are not representative given the number of political ads we review daily across the world” and went on to say that their ad review process has several layers of analysis and detections, and that they invest many resources in their election integrity efforts. Their full response is included in the end note.

YouTube

As with Facebook, we used a dummy account set up in the UK to place the ads that had not gone through YouTube's Election Ads verification or advertiser verification process.

Within a day, half of the ads that we had attempted to post on YouTube had been rejected by YouTube. A few days later, YouTube had rejected all of our ads – and critically, had also banned the dummy YouTube channel that we had set up to host the ads. However, our Google Ads account remains active.

It appears from our experiment that YouTube’s policy enforcement regarding election disinformation in ads in the US is working as intended when tested with blatant disinformation as in this experiment, and with ads posted from outside of the US.

While this is good news for the US, YouTube’s inability to detect similar election-related disinformation in Brazil – approving 100% of the ads tested there – shows that there are still major gaps in international enforcement of its policies.

Google did not respond to our request for a comment.

TikTok

We again used a dummy account to place the ads on TikTok, with the account set up and ads posted from within the US. TikTok does not allow any political ads.

TikTok performed the worst out of all of the platforms tested in this experiment, with only one ad in English and one ad in Spanish – both relating to covid vaccinations being required for voting – being rejected.

Ads containing the wrong election day, encouraging people to vote twice, dissuading people from voting, and undermining the electoral process were all approved. The account we used to post the election disinformation ads was still live until we informed TikTok.

A TikTok spokesperson said in response to our experiments that “TikTok is a place for authentic and entertaining content which is why we prohibit and remove election misinformation and paid political advertising from our platform. We value feedback from NGOs, academics, and other experts which helps us continually strengthen our processes and policies.”

Online election disinformation in the US

Disinformation in high-stakes elections, particularly on social media, has been highlighted with examples stemming from the UK’s 2016 Brexit referendum right through to the first round of the Brazilian election earlier this month.

Since the 2020 US elections, disinformation specifically aiming to delegitimize voting by mail and calling into question the integrity of election officials such as ballot counters has become considerably more prevalent in the US.

In August 2022, the House of Representatives published a report named “Exhausting and Dangerous: The Dire Problem of Election Misinformation and Disinformation" that examined the challenges facing elections in the US stemming from the 2020 elections.

It specifically highlighted attacks on the mail-in ballot system and election officials. Additionally, the Federal Elections Commission and Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency published documents highlighting common types of disinformation and the reality behind the tropes.

YouTube (247 million users), Facebook (226 million users) and TikTok (estimated 85 million users) are some of the most widely used social media platforms in the US.

What needs to change

First, we call for mandated universal ad transparency for digital platforms. Universal ad transparency is a crucial element to provide ways for researchers and the public to hold social media platforms accountable to policies on political ads, discrimination and other standards.

We were encouraged to find that YouTube’s election integrity measures are working as intended in the US. However, the platform must ensure the same measures are rolled out in future elections around the world, to protect their users globally.

For Facebook, two things are clear: Firstly, that its election integrity measures are still ineffective. Meta must recognize that protecting democracy is not optional: it’s part of the cost of doing business.

Secondly, it’s evident that Facebook is able to protect elections from disinformation when it chooses to.

While between 20% and 50% of the ads we tested got through in our experiments, this was still a considerably stronger result than in other countries where we have tested its content moderation efforts.

Our findings in Myanmar, Ethiopia and Kenya show that Facebook’s content moderation efforts are seriously lacking – reinforced in Brazil, where the bar for advertising with explicit political content is ostensibly even higher as ad accounts must be authorized.

C4D and KU Leuven researchers have found that Facebook’s record on identifying political ads is severely lacking, especially outside the US.

Our findings also again suggest that Facebook’s account authorizations process – a compulsory measure for anybody wanting to post political or social issue ads – is opt-in, and easily circumvented.

This means that Facebook’s own ad library, its “most comprehensive ads transparency surface”, does not give full transparency into who is running ads, who was targeted, how much was spent and how many impressions the ads received.

This information is vital so researchers, journalists and policymakers can investigate what’s going on and suggest interventions to help protect democratic systems.

For TikTok: while the policy exists to ban political ad content, it’s only as strong as its enforcement. In approving 90% of the ads that we tested containing election disinformation for publication, it’s showing a major failure in its enforcement capabilities.

Like Facebook, TikTok must recognize that protecting democracy is not optional: it’s part of the cost of doing business.

Our findings reinforce the need for TikTok to invest in a comprehensive and robust repository of all ads running on the platform to enable community oversight of TikTok’s policy enforcement and support independent research into the online political advertising ecosystem.

YouTube has shown us that preventing election disinformation is possible – when it chooses to do so. We call on the platform to ensure that its efforts to prevent election disinformation are rolled out globally. And as with TikTok and Facebook, we encourage YouTube to increase transparency and place all ads, globally, into its ad library.

While the EU is taking a lead globally to regulate Big Tech companies and force meaningful oversight, platforms should also be acting of their volition to protect their users fully and equally.

We call on Meta and TikTok to:

- Urgently increase the content moderation capabilities and integrity systems deployed to mitigate risk before, during and after the upcoming US midterm elections

- Immediately strengthen its ad account verification process to better identify accounts posting content that undermines election integrity

- Properly resource content moderation in all the countries in which they operate around the world, including providing paying content moderators a fair wage, allowing them to unionize and providing psychological support

- Routinely assess, mitigate and publish the risks that their services impact on people’s human rights and other societal level harms in all countries in which they operate.

- Publish information on what steps they’ve taken in each country and for each language to ensure election integrity

- Include full details of all ads (including intended target audience, actual audience, ad spend and ad buyer) in its ad library

- Allow verified independent third party auditing so that they can be held accountable for what they say they are doing

- Publish their pre-election risk assessment for the US

We call on YouTube to:

- Increase the content moderation capabilities and integrity systems deployed to mitigate risk before, during and after other elections globally, not just in the US

- Publish information on what steps they’ve taken in each country and for each language to ensure election integrity

- Include full details of all ads (including intended target audience, actual audience, ad spend and ad buyer) in its ad library

- Allow verified independent third party auditing so that they can be held accountable for what they say they are doing

- Publish their pre-election risk assessment for the US

TikTok and Facebook fail to detect election disinformation in the US

Download ResourceNotes

Cybersecurity for Democracy is a research-based, nonpartisan and independent effort to expose online threats to our social fabric – and recommend how to counter them. We are part of the Center for Cybersecurity at the NYU Tandon School of Engineering.

The ads were in the form of a video (text on a plain background) and were not labelled as being political in nature.

Researchers interested in knowing the exact wording of the political ad examples we used are welcome to request this from us by writing to [email protected]

Facebook's full response to our opportunity to comment letter:

"These reports were based on a very small sample of ads, and are not representative given the number of political ads we review daily across the world. Our ads review process has several layers of analysis and detection, both before and after an ad goes live. We invest significant resources to protect elections, from our industry-leading transparency efforts to our enforcement of strict protocols on ads about social issues, elections, or politics – and we will continue to do so."

Read this page in