Introduction

Imagine that you’ve spent years studying glacial retreat in the Arctic. You believe you have a duty to share your findings that reveal how our world is changing with a wider public. But you remember having trouble sleeping after getting hateful messages on Twitter the last time you published your work there, and the death threat your colleague received after talking about her work online. Do you hold off from posting?

For decades, scientists have been documenting changes in the earth’s climate and warning of the effects. Their findings underpin government declarations of climate emergency and policy responses. But our new investigation reveals that online harassment and abuse against climate scientists imperils their work and ways of communicating.

In a survey of 468 scientists around the world working on climate topics, we found online abuse is common, and for many takes a mental and physical toll that inhibits climate discourse. Yet there are ways to stem it. Most abuse took place on Twitter and Facebook, platforms that can instead make reforms to protect scientists and enable informed publics and responsive climate action.

Note on sampling: In late 2022 we contacted climate scientists and experts via publicly available lists and asked them to complete an online survey hosted by YouGov. The responses are based on natural fallout, meaning anyone invited could complete the survey. Of the 468 that completed the survey, 183 said that they have experienced online harassment or abuse, with effects on health, work, and communication.

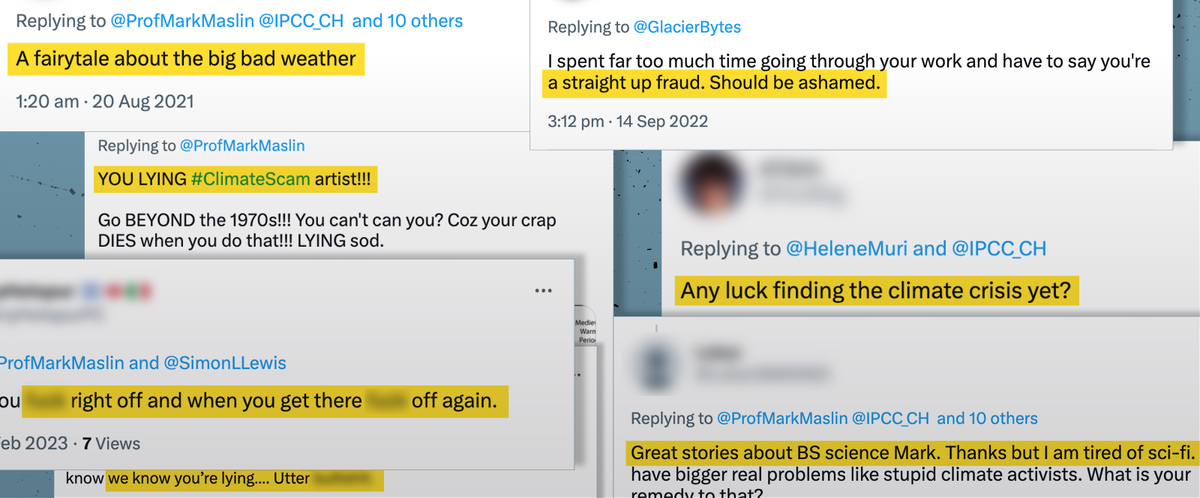

A tweet directed at academic Mark Maslin

What we found

Half of climate scientists surveyed with more than 10 publications have faced online abuse

The survey found that level of exposure to harassment was linked to amount of academic publications and frequency of media appearances. Overall, 39% of all scientists polled (183 out of 468) have experienced online harassment or abuse as a result of their climate work. This rate is lower for those who have published fewer than six articles (24%) and increases to 49% of scientists who have published more than 10 journal articles.

The results suggest abuse increases with both academic output and media exposure. Of those scientists who are in the media at least once a month (13% of respondents), 73% have experienced abuse, and 29% reported having experienced ‘a great deal’ or ‘a fair amount’ of abuse. Even for those scientists who have never made any media appearances (19% of respondents), 12% reported they have experienced online abuse.

Women more targeted on appearance and threatened with violence

Most recipients of abuse have had their credibility (81%) or work (91%) attacked, but for those scientists who identified as female, personal characteristics were also common targets. Their sex or gender was targeted a great deal or a fair amount for 34% of affected women and only 3% of affected men. Similarly, women were three times as likely as men to receive a great deal or a fair amount of harassment on the basis of their age (17% to 5%), and received more threats of sexual violence (13% of affected women) and physical attacks than men. Almost a fifth (19%) of women and 16% of men who had faced harassment had received threats of physical violence.

> 1 in 8 female scientists who reported experiencing online harassment had been threatened with sexual violence.

I think there is also a cost to having to explain yourself like you are responsible for the issues of the world - there is a lot of pressure to not only do the work, but to do it under pressure and to explain it to all audiences and it isn't a part of your identity you can leave behind on social media.

The effects of the abuse are wide-ranging, but particularly worrying is the fear for damage to professional reputation (affecting over half of harassed scientists who responded to the survey) and for personal safety (21%). 51% report anxiety caused by the abuse, and 21% of women report physical illness resulting from the stress. Over a fifth end up dreading work, and nearly half (48%) report a loss of productivity.

Of those scientists who experienced abuse as a result of their work on climate:

> Nearly a third (32%) of women reported experiencing sleep problems.

> More than a fifth (21%) of scientists reported having experienced depression.

> 8% have received death threats.

Harms to scientists hurt us all

These trends present concerns for the global ability to act on climate change. If scientists are unable to do their work because of stress and fear caused by harassment, the critical evidence that undergirds climate action and solutions is put at risk.

Similarly troubling is the possible chilling effect online abuse has on scientists’ participation in public discourse. 41% of affected scientists polled said their experience had made them less likely to post on social media about climate issues. However, 23% of affected scientists reported that their experience had made them more likely to do so, which suggests many scientists are determined to communicate climate topics on social media in spite of the risk they may receive harmful content.

It shouldn’t be like this: all climate scientists should feel able to share their work online, not just those prepared to deal with ensuing abuse.

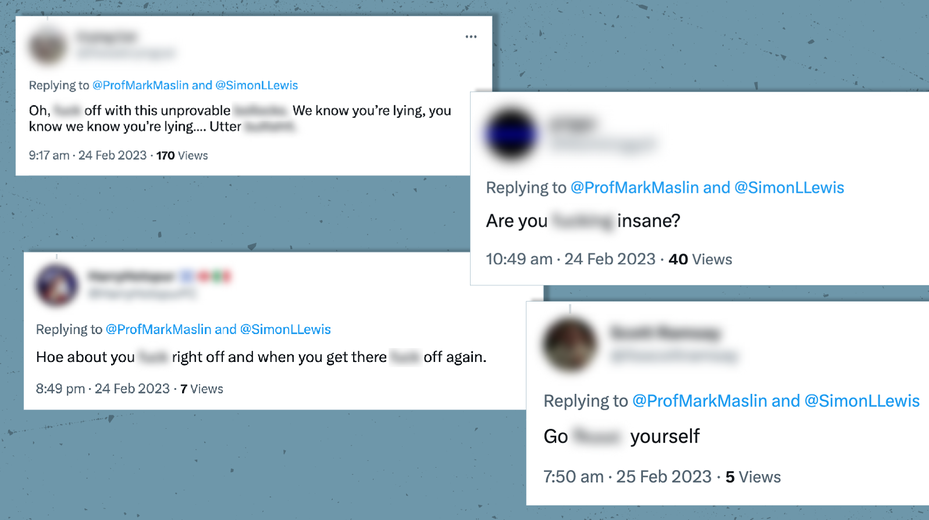

Tweets directed at academic Mark Maslin

Case study: Dr. Mark Maslin

Professor of Earth System Sciences at University College London

Most of the harassment I get is on Twitter, where there’s a set of climate change deniers who go after climate scientists with three different approaches. The first one is: ‘you’re wrong, show us the evidence’ – just trying to suck you in and waste huge amounts of time. There are others that say, ‘oh, well of course you’re paid to say that, that’s your job, et cetera.’ And then there’s the straight up insults. Interestingly enough, I would say that those had been in decline. I think it was also helped that Twitter was taking an active role in policing critical issues.

Recently, I’ve noticed an uptick in the stupid comments approach. I find it depressing that I put something out that’s very logical, which is ‘if we all eat a lot less meat, we’ll live a lot longer and be healthier – it would also mean using less land and water in food production and emitting a lot less carbon emissions, so would help save the planet.’ And you get all this abuse, like ‘you’re trying to break my liberties,’ with no understanding of the political way the world works, and this is really worrying and sometimes undermines my faith. And I think it’s also because social media skews the numbers of people appearing to behave like this. I might get 1,000 likes for a tweet and maybe 10 nasty comments – but it is those comments we remember.

Tweets directed at academic Mark Maslin

The problem I have also encountered is of course that the more we’ve become strident, particularly about climate change, the less we have talked about the other issues. It’s not just climate – it’s pollution, plastics, deforestation, biodiversity, it’s all human impacts that are important.

How do we add all the other issues in so people can see that? I keep including the human – one tweet I send out a lot points out that the richest 10% of the world’s population emits 50% of the carbon pollution. This is not about emissions, it’s about inequality. It’s not because we have too many people, it’s because we have too many rich people consuming too much. Of course, once you start pointing these things out – you get accused of being political and being a socialist or a communist – it is as if 8 billionaires owning the same wealth as the poorest 4 billion people is a natural state of humanity.

Case study: Dr. Shouro Dasgupta

Environmental Economist at Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change | European Institute on Economics and the Environment

I’ve seen my fair share of online harassment. I’m not in the top echelon of climate experts, but I have published a fair amount in the last five years or so, and I do quite a bit of media as well. Any time I do media, there is some harassment on Twitter and on Facebook. And it often comes from, of course, the usual suspects – the climate deniers, the army of bots, unpleasant people in general.

People being racist, calling all sorts of colourful names, and bullying – these are not uncommon. Most of the harassment I receive is racist in nature partly because they can’t question my expertise, so they question and attack what is unnatural to them, which is race. Mostly this happens in private messages, which is why many researchers keep their direct messages closed.

As climate scientists and researchers, we need to communicate better to the general public. Unlike the climate sceptics, we actually have a duty to stick to the truth. I’ve tried to improve my Twitter game by being more strategic, using less jargon, and trying to ensure that my tweets, even about technical papers, are understandable to the public. I’m an economist, so it’s a dismal science to begin with, but researching the impacts of climate change is what I do and it’s often doom and gloom. So one thing we must do better is give out positive messages that we can make a change.

Case study: Dr. William Colgan

Senior Researcher at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland

The experience I had that was the most hate-filled was probably about four months ago, when Greta Thunberg retweeted me. And it was just a random tweet saying, ‘Hey, here we are at climate strike’ on a random Friday, a little video of kids walking through the streets in Copenhagen. Not a very controversial post, but she retweeted that and she has a big reach and this massively galvanized following. And for months after that, this one tweet was still getting retweeted and propagated, it echoed for much longer than a regular tweet, and so did the hate comments. And the hate comments were disproportionately high on that one tweet. I think it was obviously because Greta had endorsed it or retweeted it, and it really made me realize just how it multiplies - the higher your public persona the hate multiplies disproportionately.

Twitter was pretty good, in that you could find all the viewpoints on Twitter. It was kind of a public space for ideas. But now the climate scientists that I follow - including myself, now I have a Mastodon account - it’s like we’re withdrawing from that space to our own safer space, which is probably not the best thing. We don’t have a climate science crisis right now, we have a climate science communication crisis - we need to be doubling down on explaining climate science at this particular moment, and instead it feels like we’re withdrawing from the main public space. And I don’t feel good about that, but everybody’s got a day job – what do you want to do after you’ve done your day job, which is doing the actual science, how much time and energy do you want to invest fighting battle after battle on Twitter?

A tweet directed at William Colgan

It makes me more shy and careful about putting myself into the mix, so to say. But that’s the problem I think, is that scientists often feel, ‘well, I will just talk about my work, I’ll talk about the science, and people can’t really get too mad at me then.’ But I feel what the world needs is scientists to actually make political statements, or at least talk about the political implications of the work. Not just say ‘the ice sheet is losing this much ice,’ but say ‘the ice sheet is losing this much ice, therefore we must embrace the Paris agreement in full to try to counteract this.’ I think that extra step is often where you get the hate. And the hate makes you less willing to take that extra step, when that extra step is what we need right now.

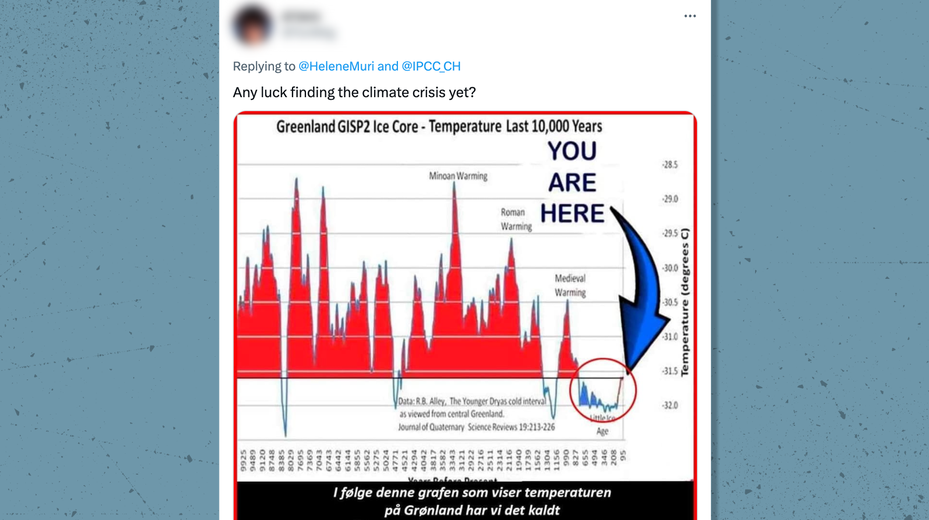

Case study: Dr. Helene Muri

Senior Researcher at Norwegian University of Science and Technology

It’s been a number of incidents either on social media or on message boards or comments on articles or via emails, but also phone calls directed to myself and my family or to my employer as well. It happens on a regular basis. I’m often interviewed by the media on a number of different topics, ranging from extreme weather events, to climate change, to assessment of mitigation options. The more extreme cases are comments in the direction that I should kill myself in such and such a way. Or the worst one is when they say that they are going to hunt me down and do various things to me. And what I appreciate even less than that is when they are calling my father up and saying various things to him. Other times it’s just gender comments as well, ‘I should let the men take care of this kind of research.’

A tweet directed at Helene Muri

I keep communicating, but every time I engage, I also try to gauge what the repercussions could be and what are the benefits, and the benefit-risk analysis aspects of it. And so some things I’ve declined, and also because I’ve done quite a lot of press I don’t feel I need to accept and do everything. But I still try to engage as much as I can because climate change is a much bigger issue than the consequences that I am experiencing from actively engaging in communication.

It’s my impression that the women get a worse deal than a lot of the men. But I also know that some of the more vocal climate scientists, no matter the gender, have had some rather unpleasant experiences as well.

Reforms and recommendations

We’ve been here before – but tech companies have the power to change the record

Harassment of climate scientists and experts is not new. It has included email intimidation campaigns and abuse of Freedom of Information requests to impede the work of noted climatologists. A 2018 article suggested sexist attacks against climate scientists were on the rise. Recent studies into the experiences of Covid scientists found similar results connecting media exposure to harassment or abuse including death threats.

Although the responses to our survey showed attacks also took place in channels such as emails, blogs and comment sections, the most commonly reported venues were social media platforms. For the scientists surveyed who said they had experienced abuse, Twitter (44%) was the most cited platform on which abuse had taken place, followed by Facebook (31%). And the Pew Research Centre found in 2021 that, “while these kinds of negative encounters may occur anywhere online, social media is by far the most common venue cited for harassment.” These companies also have the power to tackle the spread of harassment on their apps.

Reforming a business model that drives abuse

Incitement and harmful speech predates – and may outlast – today’s big social media companies, but the companies have much to account for in its dissemination, and have the means to limit its reach.

Crucially, there’s the business model. For Facebook and Twitter, this consists of profiling users by collecting lots of data about them, then targeting them with content and advertising they are most likely to engage with. Studies show that on social media anger has more traction than other emotions and that misinformation travels faster than truth. By boosting such content, social media platforms help give rise to dangerous falsehoods, societal division and even violence. This also makes it harder to distinguish fact from fiction and advance collective action on the climate and other pressing challenges.

The algorithmic systems that determine what content is shown to users are kept opaque by the companies, despite their influence on how hundreds of millions of people interact with each other online and the way they see the world. Companies need to allow independent evaluations of their algorithms and commit to respecting user safety and rights.

The death (and rape) threats were extended to my children

Taking content moderation seriously

More immediately, social media companies can improve the resourcing and transparency of their content moderation systems.

In numerous investigations into Meta’s ability to detect hate speech and other prohibited content, we have found the company frequently fails to enforce its content moderation policies. Much of the abuse we uncovered in our survey – such as threats of physical or sexual violence and death – are prohibited by all the big social media platforms.

Instead of enabling a harmful environment, they should be quicker to act on content that clearly violates their policies and conduct human rights impact assessments of their processes.

Properly resourcing their content moderation systems would help reduce the amplification and spread of disinformation around climate or climate science, and incendiary or hateful content. Platforms should provide sufficient support to moderators across the globe and the different languages used on the platform. They should regularly review the effectiveness of their processes, inviting external input and disclosing their actions and findings with users.

The way forward for technology and climate

These companies must cease the surveillance of people’s activity and amplification of harmful content. The climate and digital rights movements share common cause in this goal, and need to work together to achieve it. At stake are the democratic processes, from electoral integrity to civic discourse, that are essential to enabling climate action and the protection of human rights worldwide.

A note on methodology

Global Witness sent a survey invitation by email to approximately 24,000 scientists and experts around the world working on climate topics using public academic contact lists. The recipients were identified from having published scientific papers on climate change or global warming, or being listed in groups of climate experts including the Global South Climate Database. The survey was hosted by YouGov and carried out online. The total sample size of respondents who completed the survey was 468 climate scientists and experts and of this, 183 said they had experienced a ‘great deal’, ‘fair amount’ or ‘not very much’ online harassment or abuse. The survey was live between 18th November - 20th December 2022. Full results are available at this link.

Climate scientists who completed the survey could be those who have published research or commentary on climate topics to complete the survey, whether or not they had experienced online hate or harassment. Nevertheless, as with other surveys of this type, the 468 people who responded did so voluntarily and may not represent the experiences of all climate scientists as the responses were based on natural fallout, and no controls or sampling quotas were in place.