New evidence suggests links between a politically-connected PR firm and an online smear campaign targeting Global Witness and partners.

In July 2020, Undermining Sanctions, a joint investigation by Global Witness and the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa (PPLAAF), uncovered evidence indicating controversial mining magnate Dan Gertler may have used an international money laundering network to attempt to evade United States sanctions and continue doing business in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

The report caused an outcry and prompted vehement denials, with lawyers for Afriland First Bank – a Congolese bank implicated in the investigation – filing a criminal complaint in France the day before publication.

In the months that followed, the bank also filed complaints in DRC against two former Afriland employees, Gradi Koko Lobanga and Navy Malela Mawani, who after blowing the whistle internally to no avail had decided to share banking information with PPLAAF and then Global Witness. They subsequently left the country, fearing for their safety.

As a result of these complaints, the two whistleblowers were convicted and sentenced to death in absentia by a Congolese tribunal. This shocking judgement is based on a grossly unfair, irregular and secretive judicial process.

Several other complaints have been filed in France by individuals mentioned in the report and an Israeli lawsuit has been brought against one of Global Witness’s media partners, Haaretz.

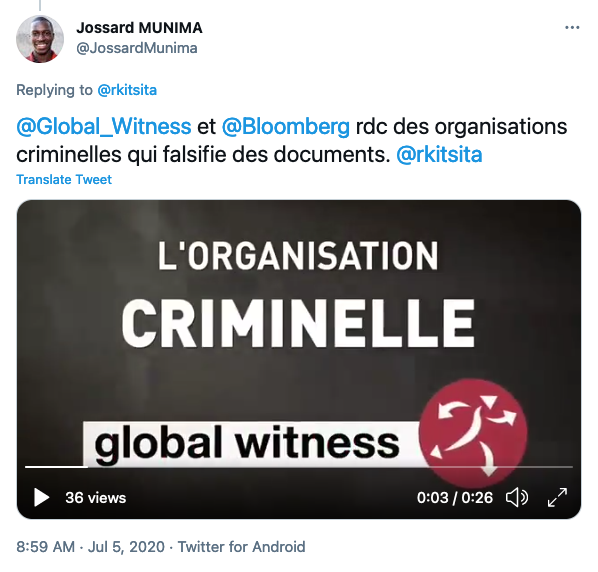

In parallel with this flurry of legal activity, last summer a network of social media accounts sprang into life, sharing slickly-produced videos charging Global Witness, PPLAAF and their media partners with bizarre allegations of corruption, extortion and bribery in an apparently coordinated smear campaign.

Another, similar campaign appears to have been launched recently, around the time of the publication of new revelations by PPLAAF, with two anonymous pieces of ‘promotional content’ on an Israeli news website and a promoted YouTube video making similarly baseless allegations.

While the individuals or companies behind the latest campaign are not yet known, research by Global Witness’s Data Investigations Team now links the original campaign to a communications agency with a history of work for former DRC president Joseph Kabila, presidential candidate Emmanuel Shadary and the state mining company, Gécamines.

The connections appear to suggest an attempt by figures at the heart of Kinshasa’s political and business elite to stifle legitimate journalism and mislead the public in DRC and internationally, using social media as their weapon of choice.

“Uniting Africa through digital"

At first glance, Jossard Munima appeared to be a concerned Congolese citizen: his Twitter profile described him as an “entrepreneur, patriot thinker” and the picture showed a smiling young man in a red shirt.

His tweets, however, looked odd, mixing short messages using American slang with posts in French advertising the local bank Rawbank and apparently promoting the Registre des Appareils Mobiles (RAM), a controversial government initiative to create an official register of mobile phones in DRC.

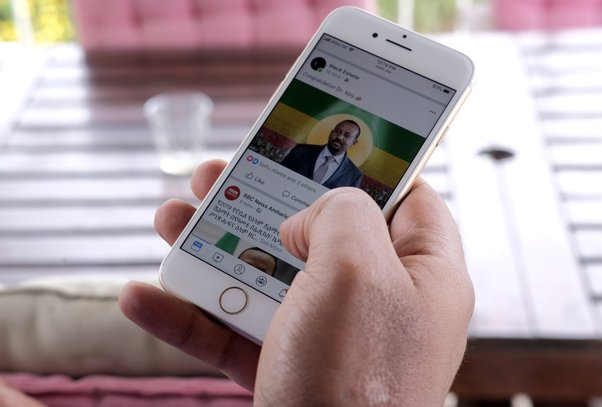

Among these seemingly promotional tweets were messages attacking Global Witness and partners over Undermining Sanctions. Acting in concert with other Twitter users, Munima posted and recirculated videos and other posts attempting to cast doubt on the report and undermine its findings.

On closer inspection, ‘Munima’ appears to be part of an astroturfing operation – an online identity used to fake grassroots opposition. The profile picture was a stock photo: zooming in showed a watermark from an Australian company called Envato, and the same model appeared in advertising material for RAM, wearing exactly the same red shirt.

Data from Twitter’s application programming interface (API), a tool for software developers, shows that the Munima account was created on 5 June 2020, well after allegations had been put to the subjects of Undermining Sanctions and within 20 minutes of two other accounts – both purporting to be young Congolese men – which would go on to post similar content.

Who was behind these accounts? The recovery email address shown for each one – a redacted version of the address used to register it – followed the same format. In the case of Munima, the address given was jo***********@d****************.***, likely corresponding to the account’s username, ‘jossardmunima’, and a domain name of 17 characters, beginning with the letter ‘d’.

Through programmatic testing of addresses using Twitter’s ‘find your account’ form, a list of hundreds of thousands of matching domain names was narrowed down to one: digitalopencircle.com, registered on 14 March 2020. Email addresses associated with the same domain name were used to register at least ten accounts in the weeks surrounding the publication of Undermining Sanctions.

What is Digital Open Circle?

As of September 2020, the digitalopencircle.com website consisted of an empty template featuring the branding of Black Box FM , a radio station apparently owned by the chief executive of a Congolese communications agency called CMCT TCG. According to what appears to be an official Facebook page created on 11 March 2020, Digital Open Circle – which uses the slogan “Uniting Africa through digital” – is an initiative of Congolia, a startup incubator based in Kinshasa and seemingly also owned by CMCT or its chief executive.

There are further links to CMCT. As well as following each other in an apparent effort to create the illusion of an organic social network, all ten of the suspicious Twitter accounts registered using the Digital Open Circle domain name followed an account under the name Tony Badika. Unlike these accounts Badika is an actual person – according to his LinkedIn page, he started working for CMCT as a web marketing specialist in May 2020.

Responding to questions posed by Global Witness, Badika confirmed his employment at CMCT but rejected the suggestion that being followed on Twitter by the accounts in question implicated him in their activities. He also stated that he did not know anything about Global Witness’s description of a social media smear campaign conducted against Undermining Sanctions.

Digital Open Circle, then, appears to be closely connected with CMCT, a communications agency. But who is CMCT's chief executive, and who are the company’s clients?

The “kingmaker”

Jean-Claude Eale Balangy was born in the late 1950s, during the political upheaval that would lead to Congo’s independence from Belgium. More than half a century on, as chief executive of CMCT, he presents himself as a powerful figure in Congolese politics and society.

Eale has been described as a “kingmaker”, albeit by a magazine he himself edited. While the extent of CMCT’s work isn’t clear, the company – founded in 1994 according to its LinkedIn page – has consulted on election campaigns across central and southern Africa: for Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe in 2008 and 2013, Denis Sassou Nguesso in Congo-Brazzaville in 2016, and for Joseph Kabila and his heir apparent, Emmanuel Shadary, in the DRC elections of 2006, 2011 and 2018.

CMCT’s association with the structures of power in its home country is particularly strong. As well as working for politicians and political candidates in DRC, publicity material and video footage posted online suggests that CMCT has advised the country’s state-owned mining company, Gécamines, and its chairman Albert Yuma, who Global Witness previously accused of failing to safeguard more than $750 million in revenues from DRC’s massive mineral deposits. In response, Gécamines said the report was inaccurate and disputed the figure.

Alongside campaign material for Kabila, a CMCT showreel posted on YouTube includes footage from a 2018 Gécamines press conference held to counter allegations put forward by NGOs including Global Witness. Eale’s YouTube account hosts several PR films for Gécamines and Yuma, while promotional videos for a deal between Gécamines and the China Nonferrous Metal Mining Group (CNMC) – which Global Witness has also previously reported on – bear the CMCT logo. Neither Gécamines nor CNMC responded to questions about the mining deal put to them by Global Witness last year.

The connections to public and quasi-public bodies in DRC don’t stop with Gécamines. In addition to its apparent work for the state mining company, CMCT has produced print material for the powerful Fédération des entreprises du Congo (FEC), until recently chaired by Yuma, and managed advertising space on vehicles run by Transco, Kinshasa’s bus company. The award of the Transco contract to CMCT in 2015 was controversial, with two rival companies claiming that it had been taken from them after a legitimate procurement process the previous year. Assessing the case, DRC’s public procurement agency dismissed the claims, concluding that the original award had not followed the appropriate procedures.

Meanwhile, a 2020 report by DRC NGO Observatoire de la Dépense Publique (ODEP), an independent public spending watchdog, accused Transco and CMCT of irregularities in the way that revenue from the advertising contract had been handled, claiming that the bus company’s chief financial officer would collect its share of the revenue by withdrawing $20,000 in cash from CMCT each month. Transco denied the NGO’s allegations, saying that the amount of revenue varied from month to month and that it was always sent by bank transfer.

Congolia, CMCT’s startup studio, worked with the DRC government to release a COVID-19 tracking app in March last year. The incubator appears to host more sensitive digital communications work, too. Among the projects listed on its website is QG2CRISE, a boutique crisis communications agency whose “knowledge of Congolese economic, political, cultural and media networks enables us to effectively support Congolese and foreign companies, organizations and institutions with communication, image and reputation issues in the DRC”.

As an example of a situation in which its work might have been of use, QG2CRISE’s website describes a 2020 scandal involving Rawbank, which regularly features in posts from the suspicious Twitter accounts discussed above, though it is unclear if QG2CRISE ever actually advised the bank. In 2017 Global Witness accused Rawbank of handling almost $88 million in anomalous payments from Gécamines. Responding to allegations posed at the time, Rawbank said that it could not comment on transactions due to banking and client secrecy rules, but that it aimed to contribute to improved economic governance and transparency.

Eale’s links to Congo’s elite extend beyond CMCT and its associated companies – according to his LinkedIn page, he has also been vice-president of DRC’s sports federation, a member of the Congolese Olympic committee and head of a commission at the FEC, the country’s employer’s association, during Yuma’s chairmanship.

In August 2020, in response to the murder of two twins in Kongo Central province, Eale started a social media campaign – ‘450 Egal 1’ – to try to counter ethnic conflict in DRC. Among dozens of ambassadors for the campaign listed on his Facebook and Twitter pages is Alain Mukonda, a Kinshasa businessman who, according to evidence presented in Undermining Sanctions, appears to have moved more than €11 million in cash into companies linked to Dan Gertler.

Responding to the allegations, Mukonda denied being a partner of the Israeli businessman or having ever acted for him. There is no evidence to suggest that Mr Mukonda had any connection with the smear campaign.

Neither Eale nor CMCT responded to requests for comment on the social media smear campaign apparently conducted against Global Witness and partners, though staff at CMCT did suggest that Eale may not have been contactable at the time of Global Witness’s approach for personal reasons. There is no evidence to suggest knowledge on Eale’s part of the activities of any CMCT employee or direct involvement in the campaign.

What’s at stake

The links between the Twitter accounts used to circulate material critical of Undermining Sanctions and CMCT seem clear. The accounts, all created at around the time of the report’s publication, could only have been registered by somebody with access to email addresses associated with the digitalopencircle.com domain name. While ownership details for the domain name have been anonymised, it was registered three days after the creation of the Digital Open Circle Facebook page, labelled explicitly as an initiative “from Congolia ”.

Whether the social media campaign was commissioned by a client of CMCT – and if so, which client – is harder to assess. There is no evidence that attacks on Global Witness, PPLAAF and media partners by inauthentic social media accounts were ordered or otherwise caused by Gécamines, Yuma, Mukonda, Gertler or anyone else mentioned in this article. Nevertheless, the tone and content of the posts, combined with the subject matter of the report and CMCT’s previous work for high-profile clients in DRC, raise questions about the motives behind them.

While the ultimate source of the attacks may be unclear, our findings lead us to believe there was an orchestrated attempt to silence Global Witness and to divert the conversation from the publication of Undermining Sanctions, which aimed to expose suspicious activity in DRC’s mining sector. Social media accounts with false and damaging content have contributed to the polarisation of Congolese civil society, led to vociferous attacks by local NGOs and fed into misleading reporting in the press.

The magnitude of the smear campaign faced by Global Witness and others sends a worrying message to Congolese civil society and activists, who continue to take tremendous risks to fight corruption. And as the appalling court judgement against the whistleblowers has shown, it is the Congolese people who will pay the highest price.

Download PDF version: Corporate connections and Twitter tricks

Download Resource