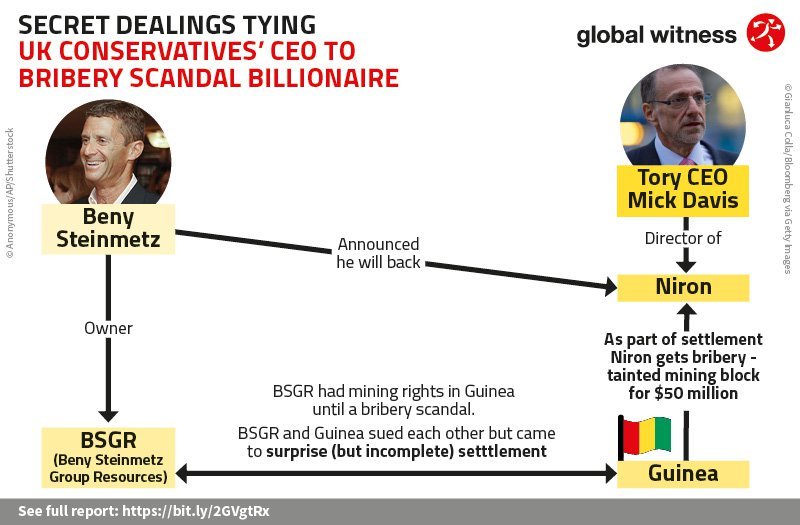

A company fronted by the Chief Executive of the British Conservative Party is set to pay $50 million to seal a deal between the government of Guinea and a mining firm that has engaged in high-level bribery there. The controversial deal, seen by Global Witness, aims to extricate billionaire Beny Steinmetz from criminal investigations that have been launched in Switzerland, Israel and elsewhere

Global Witness has previously exposed how the company BSGR, led by Steinmetz, bribed the wife of the Guinean president to obtain one of the world’s largest iron ore concessions in 2008.

Those corrupt practices led Guinea to eventually cancel BSGR’s mining rights in 2014, sparking a long-running legal dispute between Guinea and BSGR.

The latest deal involving Mick Davis – who is both Chief Executive and Treasurer of the Conservatives – purports to resolve that dispute.

The payment and other key details have until now been kept secret.

Under the deal, struck by BSGR and Guinea in February, Niron – the company headed by Davis – will get rights to mine a concession called Zogota.

This was one of the blocks withdrawn from BSGR over corruption. Steinmetz is now to be a co-investor alongside Niron.

At the same time, Guinea is to withdraw from criminal proceedings targeting Steinmetz in Switzerland and has promised not to make any “disparaging remarks” against Steinmetz or BSGR for 10 years.

Niron belongs to a secretly-owned firm in the Bahamas, according to documents in the UK’s corporate registry.

Taken together, these revelations mean there are serious questions to answer for one of the governing Conservative Party’s most important back-room operators.

Why is he playing a key role in such a controversial deal? Why has he decided to team up in Guinea with a billionaire whose company has an established record of bribery there? And who are Niron’s secret financial backers?

The opaque settlement process also involves the world’s fifth biggest accountancy company, BDO, which signed off the new arrangements in its position as administrator of Steinmetz’s stricken company.

Bribing the president’s wife

Between 2012 and 2014, Global Witness exposed how BSGR bribed the wife of Guinea’s then-president with millions of dollars to obtain a gigantic iron ore concession in the Simandou mountains, a lush forested area home to endangered West African chimpanzees and white-lipped frogs.

Once BSGR got the rights in 2008 it promptly sold half of them to the world’s number one iron miner, Vale, for $2.5 billion – twice Guinea’s entire national budget at the time.

In 2012, a new Guinean president launched a corruption inquiry into the granting of BSGR’s licences, resulting in the cancellation of the Simandou blocks as well as rights to nearby Zogota.

BSGR then took Guinea to arbitration at the International Court for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in Paris in 2014, whereupon Guinea counter-sued.

All the indications were that BSGR was heading for a major defeat.

But in February this year, Guinea and BSGR stunned observers after suddenly agreeing to end the dispute, in a deal brokered by former French president Nicolas Sarkozy.

BSGR crowed that it had been cleared. Beny Steinmetz told Bloomberg: “We were enemies. Now we are friends and partners with the Guinean government. We have both put aside the past and BSGR and its employees and advisers have been vindicated.”

But earlier this month BSGR lost a second arbitration case relating to the deal, this time against Vale in London. It was ordered to pay out a whopping $1.25 billion.

The case, heard and concluded entirely in secret, was over the same issues as the Guinea dispute – notably whether BSGR had bribed the former president’s wife, Mamadie Toure.

The three arbitration judges ruled on 4th April that BSGR had indeed bribed Toure, by offering her shares to secure her “assistance in influencing [former] President [Lansana] Conte.”

“BSGR made a false representation in declaring that there had not been any bribery of Mme Toure,” reads the ruling.

In unusually outspoken remarks, the judges said it would be wrong for them “to accept bribery as a fact of life in some countries and keep eyes shut when faced with allegations of corruption.”

BSGR’s claim in February that it had been vindicated is now hard to take seriously.

BSGR has said corruption allegations are “entirely baseless” and that it always acted “to the highest standards of corporate governance.”

"Settlement" deal is only provisional

Announcing the agreement with Guinea in February, BSGR said that it relinquished its claims on the concessions under dispute in Simandou.

A “new group of investors (presented by and including Beny Steinmetz)" would instead exploit the remaining disputed mining block, Zogota.

This “new group” would include Niron – of which Davis is a director.

But the new documents seen by Global Witness show that the “Settlement Term Sheet” agreed between Guinea and BSGR in February is only provisional.

The arbitration process between BSGR and Guinea has, in fact, only been suspended, and – contrary to an announcement by the two parties – no final settlement has been reached.

The agreement is dependent on financial arrangements with Niron being formalised.

BDO would also have to carry out “due diligence” checks – which, if thoroughly conducted, should involve establishing who Niron’s financial backers and beneficiaries are.

“The discontinuance of the ICSID arbitration… should only follow once binding, definitive documentation for the Transaction has been agreed and executed by all relevant parties,” the administrators said in correspondence seen by Global Witness.

“Any Party may request that the ICSID proceeds to issue a final award if it wishes to no longer pursue the Transaction.”

BSGR and Guinea had previously released a statement saying they “jointly announce the settlement of their dispute.”

Asked about this, BSGR’s administrators said: “We are aware that statements have been made, purportedly on behalf of BSGR, to the effect that the dispute has been settled … Any third party statements were not authorised by the administrators.”

The administrators said that, in fact, “no binding settlement agreement had been reached.”

The Guinean government did not reply to questions from Global Witness.

In February Bloomberg quoted mining minister Abdoulaye Magassouba as saying the agreement is “for the good of the people. It’s with this aim that the government will try hard to work in a win-win partnership with the investors."

Tory Chief Exec’s cagey backers

“Niron Plc will pay to the Republic of Guinea the sum of 50,000,000 USD, according to a schedule to be defined between the parties,” says the Settlement Term Sheet, signed by the BDO administrators and the Guinean government.

But Niron was not even a signatory to the agreement.

However, Niron has been discussing Zogota with BSGR.

The BDO administrators refer in their correspondence to a 14 February letter from Niron to BSGR, saying that it contains further information on proposed transactions.

Contacted by Global Witness, Niron declined to say what was in the 14 February letter.

The Settlement Term Sheet ties Beny Steinmetz (officially BSGR’s “advisor”) to Niron, as it says that he introduced Niron to Guinea.

The document says: “The Republic of Guinea requested the BSGR advisor [Steinmetz], to present a new investor, Niron Plc, a well-known actor of the mining sector, with a view to mining the Zogota deposits. After examination of its technical and financial capacities, the Republic of Guinea decided to enter into a partnership with Niron Plc with a view to mining said deposits.”

“Well known” is hardly a fitting epithet for Niron. It was only registered as a company in June 2018, and it was another six months before its name first appeared in the mainstream financial press – barely a month before the agreement.

A February 2019 Niron promotional document entitled “Confidential presentation”, seen by Global Witness, says that it has more than $3 billion of capital and three nickel assets, of which two are labelled “world-class".

This document was drawn up before the provisional settlement deal, at a time when the financial press was describing Niron as a speculative venture on the hunt for mining assets.

Press reports have said that Niron was set up by Mick Davis. When first approached by Global Witness, Niron also said that Mick Davis was the majority shareholder.

But from the assets listed in the “Confidential presentation” Niron seems virtually indistinguishable from its parent company, a mysterious Bahamas-registered entity called Global Special Opportunities Ltd (GSOL).

The mining assets listed in the document are, in fact, controlled not by Niron, but by GSOL, according to comments GSOL sent Global Witness.

Questioned further by Global Witness, Niron and GSOL conceded that “at incorporation GSOL was the sole shareholder”, saying Davis would become the majority owner in due course.

GSOL was created several years ago, but its Bahamas registration allows it to keep its ultimate ownership secret. GSOL declined to disclose its owners when asked by Global Witness, saying simply that it “has many institutional and private investors” and that it is not tied to Beny Steinmetz or companies associated with him.

Niron said: “GSOL brings to Niron experience in mining, logistics and infrastructure development, as well as significant financial resources.”

It added: “Beny Steinmetz does not have a participation in Niron through GSOL but may have a minority participation directly in Niron in the future depending on the development and success of the project and subject to the agreement of all relevant parties.”

BDO, as administrators for BSGR, said: “At this stage, we are not in a position to comment on the ownership structure or ultimate beneficial owners of Niron or GSOL.”

GSOL said it operates to the “highest professional, ethical and environmental standards”. Niron says on its website that it “is committed to achieving the highest environmental, social and ethical standards in all its activities.”

Bloomberg has reported that BSGR is due to get a portion of revenues from Zogota under the new deal. And BSGR’s two administrators from BDO said in a 5 March letter seen by Global Witness that they would need “to reach an agreement with Niron regarding the revenue sharing arrangement,” which would be integral to the final BSGR-Guinea deal.

Niron said: “There are currently no revenue sharing agreements in place with BSGR but we are in discussion with the administrators of the company.”

The documents also indicate that while BSGR is technically in administration, BDO allowed Steinmetz and BSGR director Dag Cramer to negotiate with Guinea with few restrictions, expecting BDO to agree to their faits accomplis.

The administrators are due to receive over £900,000 in fees for the first year of the administration – all financed by Nysco, a Beny Steinmetz company.

The administrators appear to have been largely been left out of the loop of the settlement discussions. They were only sent a copy of the Settlement Term Sheet once it had been agreed between BSGR’s leaders and Guinea. The administrators then had it translated into English and countersigned it.

In response to questions from Global Witness, BDO wrote: “The suggestion that the potential settlement of the arbitration between BSGR and Guinea was presented as a fait accompli, which the administrators went along with, is false and misguided.”

It said that the administrators have complied with legal obligations and are acting in the best interests of creditors.

BDO said it has “made clear throughout to the company’s former management and intermediaries that they have no legal authority to, and should not purport to, commit BSGR to any arrangement without the administrators’ unambiguous express authority.”

BSGR on verge of collapse

BSGR has banked on the administration process being a form of protection, possibly against eventual adverse court rulings.

When BDO was appointed in March 2018, BSGR director Dag Cramer told Reuters his company had “voluntarily put ourselves into administration” as a means of protection against “any adverse or malicious development out of our control.”

By the time it went into administration, BSGR had already decided to cease attending the arbitration hearings with Vale, arguing that it would not be “treated fairly”.

On 27 February 2018, BSGR director Peter Harold Driver filed a confidential affidavit with the Royal Court of Guernsey, which ultimately presides over the administration process for BSGR.

He said it was “highly likely that the judgment may be handed down in favour of Vale.”

Estimating that the Vale claim would come to at least $500 million (less than half of the eventual amount), he said an adverse court decision “would leave BSGR with a deficiency of assets of at least $368 million and it is thus clearly insolvent on a balance sheet basis.”

Driver said that in such circumstances, appointing administrators was “the optimal step to protect the assets” for the benefit of BSGR’s creditors.

Yet at the same time, Driver was inexplicably upbeat about its chances in the Guinea arbitration case, saying BSGR had been advised that its “claims against Guinea are strong.”

This was despite the fact that both cases revolved around the same bribery allegations.

By the time it filed for administration, BSGR was not faring well in the Guinea arbitration. An expert appointed by the arbitrating tribunal had shot down BSGR’s claims that contracts detailing the bribes were forgeries. Guinea and BSGR then announced their unexpected reconciliation just as a final ruling was expected.

Driver also talked up BSGR’s chances of winning a $10 billion claim in New York against billionaire George Soros, where BSGR accused him of doing “anything and everything he could … to attack plaintiffs [BSGR] and falsely accuse them of corruption” in securing Simandou.

BSGR has also accused Global Witness of being part of a conspiracy, pointing to our funding from the Open Society Foundations, which was founded by Soros.

(See our response to such allegations here.)

The case against Soros has been suspended since late 2017, awaiting the resolution of the Guinea-BSGR arbitration in Paris.

Tsumani of dire developments

The key to understanding some of BSGR’s statements is their usefulness as PR, to counter a tsunami of dire developments – not just court cases but also criminal investigations in the US, Switzerland and Israel.

One of Steinmetz’s agents was convicted in New York for obstruction of justice in 2014, after the FBI secretly recorded him trying to bribe Mamadie Toure to destroy incriminating documents and telling her to lie to investigators. Steinmetz himself was arrested by Israeli police in 2016 over the Guinea affair.

Amid these events, Steinmetz and three fellow company officials also failed in a legal bid to force Global Witness to hand over its source material, where they unsuccessfully argued that our reporting on the scandal had infringed their privacy.

The Settlement Term Sheet also casts a light on the company’s determined PR effort. Guinea and BSGR undertook not to “make disparaging remarks” about each other for 10 years.

This allowed BSGR to paint the agreement in the most favourable – but misleading – light, with little fear of contradiction from the Guinean side.

But with its loss in court to Vale, BSGR must fear for its future as a going concern.

And this may not be the end of it.

On the day the agreement was revealed, the Office of the Attorney General of Geneva stated: “The corruption of foreign public officers is pursued automatically: the Genevan penal process is proceeding and the case has been almost prepared for trial.”

BSGR’s administrators said they have “received no indication that BSGR will be charged with any offence in Switzerland or elsewhere.”

Switzerland’s Tribune de Génève newspaper has, however, reported that Switzerland’s investigation into BSGR’s dealings in Guinea has focused on top figures at the company, including Beny Steinmetz.

The Settlement Term Sheet itself refers to “criminal proceedings pending in Switzerland concerning the activities of BSGR.”

BSGR denies any corruption over obtaining mining blocks in Guinea.

But Switzerland’s determination to pursue the bribery case, Vale’s victory and the possibility the Guinea arbitration case could be reopened, mean reports of BSGR’s comeback were deeply premature. This is a scandal that could run and run.