Who are the real wolves?

Leonardo DiCaprio in The Wolf of Wall Street, which was financed with money taken from 1MDB.Paramount Pictures / courtesy Everett Collection / Mary Evans

In Leonardo DiCaprio’s acceptance speech after winning a Golden Globe in 2014 for his role in The Wolf of Wall Street, he thanked the production team for the film including his collaborators “Riz and Jho”.[1]

Six months later, the US Department of Justice (DoJ) announced that these two individuals – Riza Aziz and Jho Low – were at the centre of a multi-billion-dollar corruption scandal.

It claimed that Aziz had financed The Wolf of Wall Street with money embezzled from a Malaysian government-owned company called 1MDB.

Leonardo DiCaprio and Jho Low at the French premiere of The Wolf of Wall Street. Bertrand Rindoff Petroff / Getty Images

The story of how these two Malaysian businessmen and their associates apparently embezzled billions to fund lavish lifestyles and Hollywood films is a plot worthy of a film of its own.

It’s a story of mega-yachts, luxury properties and multi-million-dollar gambling trips.

It briefly promoted Low into the world of global celebrities, earning him a reputation as a party animal.[2] Paris Hilton was photographed going clubbing with Low and posing topless on his yacht in Saint-Tropez.[3] Low also reportedly dated the model Miranda Kerr and used money from 1MDB to buy her over $7 million worth of jewellery.[4]

But it’s not just a story of glitz and glamour. It’s also a story of major banks and New York lawyers failing to prevent the flow of billions of dollars of dirty cash. And while all of this was happening 1MDB’s finances were given a clean bill of health by some of the world’s most prestigious auditors.

Jho Low and Paris Hilton in Paris in 2010.Goff Images

At Global Witness, we have been campaigning to tackle the role of professionals who enable corruption for nearly ten years, and this is one of the largest and boldest cases we have seen.

Yet while this case’s sheer size is exceptional, there is nothing unique about the ways in which those involved were able to launder the proceeds through the international financial system.

This analysis reveals for the first time the unique insights this case gives into how financial professionals enable high-level corruption.

In many ways this analysis, by following one complex case in forensic detail, sheds far more light on this system than the vast range of less detailed revelations from the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers.

This analysis does not try to cover the full story of the scandal, or of every bank or lawyer involved, but focuses on some of the most significant players in the 1MDB scandal to reveal insights about the state of the international financial system.

A global anti-money laundering system exists to prevent the laundering of the proceeds of crime through the international financial system. This costs banks and other financial professionals around $8 billion per year.5

Yet as expensive as this system is, it is not nearly as effective as it needs to be. The UN estimates that law enforcement seize and freeze less than 1% of criminal funds laundered through the international financial system.6

These rules are there for a reason. Behind every flow of laundered funds lies a crime, and those crimes have victims.

It now appears likely that 1MDB will fail to repay its debts, given the scale of embezzlement alleged to have taken place.

If that happens, the Malaysian government will face a bill greater than the country’s annual healthcare budget.7 In the end, the people of Malaysia will pay the price.

So how did these Malaysian businessmen manage to launder billions of dollars from a government-owned company through the international financial system, as the DoJ alleges?

Are the banks, lawyers and auditors involved the real wolves of Wall Street – willing to put morality and the law aside for their pursuit of profit – or are the rules just not fit for purpose?

Leondardo DiCaprio in The Wolf of Wall Street, which was financed with money taken from 1MDB. Mary Cybulski / Paramount Pictures / courtesy Everett Collection / Mary Evans

This analysis will show that for the banks involved, this was not a problem of inadequate regulations – it was a clear failure of those banks to follow the rules.

The existing regulations should have prevented the embezzlement of these billions of dollars, yet the banks ignored the rules, turned a blind eye, kept profitable clients and continued handling billions of dollars of dirty money despite clear warning signs.

This does not mean that the rules are perfect.

The lawyers involved handled hundreds of millions of dollars from the scheme, yet were never required by law to do any checks on that money.

The auditors that gave 1MDB a clean bill of health were never required to blow the whistle despite the increasingly suspect excuses given for the whereabouts of 1MDB’s billions.

Ultimately, this is a story where almost no one involved comes out looking good. It is a story of the failure of the system designed to prevent corruption on such an enormous scale.

However, that story also shows where and how action is needed to make sure such scandals never happen again.

A story of corruption and scandal

Unfortunately and tragically, a number of corrupt officials treated this public trust as a personal bank account

The alleged leading conspirators

1MDB, or 1Malaysia Development Berhad, is a government-owned company intended to promote economic development in Malaysia. Instead, it was subject to a complex scheme to embezzle billions for the benefit of a handful of well-connected conspirators.

The case concerns an elaborate fraud, implicating senior 1MDB officials, the Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak and willing partners from a Saudi oil company and the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund.

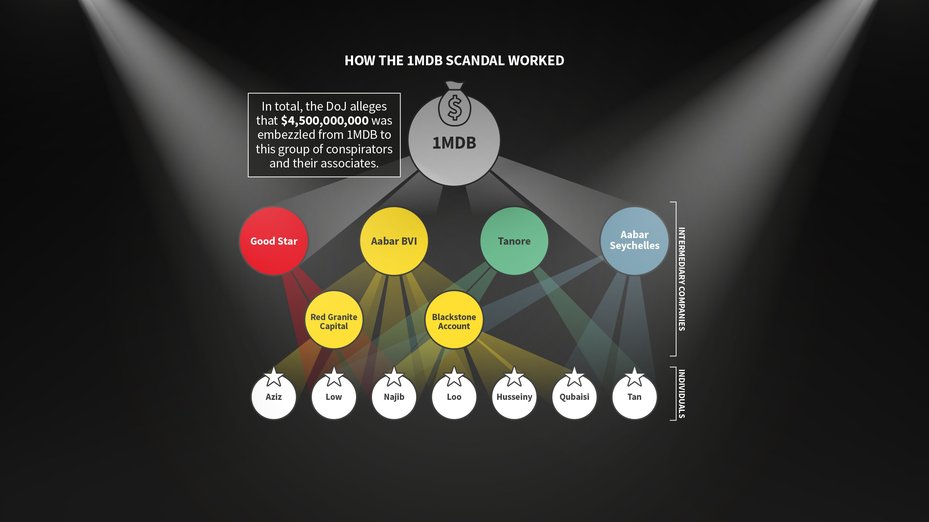

Together this group of conspirators are alleged to have embezzled billions of dollars from 1MDB and laundered it through the financial system.

The first sign of the scandal emerged in July 2015, when the Sarawak Report investigative news website published allegations that hundreds of millions of dollars from 1MDB had been transferred into Najib’s personal bank account.[8]

The full scale of the scandal, and the role of banks, lawyers and accountants in the case, was revealed in 2016 when the DoJ launched a claim to seize over a billion dollars’ worth of assets.

This case, updated in the summer of 2017, alleges that more than $4.5 billion of 1MDB funds were embezzled. It is the largest action ever brought by the DoJ’s specialist anti-corruption unit.[9]

The DoJ has now put the asset seizure case on hold while it pursues a criminal investigation into the case.[10]

The DoJ’s allegations have yet to be proven in court; however, their case documents how funds were moved out of 1MDB and into the alleged conspirators’ bank accounts, drawing on bank transfer records, internal emails and recorded calls between those involved.

For the first time, this analysis of the case gives a unique insight into the inner workings of how the international financial system enabled the embezzlement of billions of dollars out of a state-owned company.

Najib Razak, the Prime Minister of Malaysia who had overall authority over 1MDB. Mohd Rasfan / AFP/Getty Images

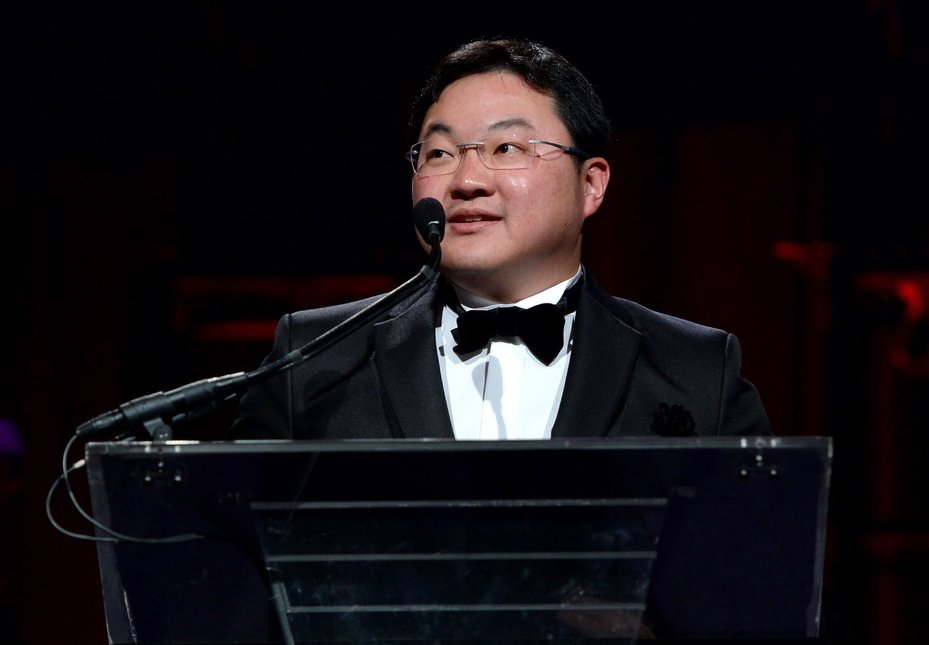

Jho Low, a Malaysian businessman and part of Najib’s inner circle. Low never held a formal role at 1MDB, though he exercised significant control over it.. Dimitrios Kambouris / Getty Images for Gabrielle's Angel Foundation

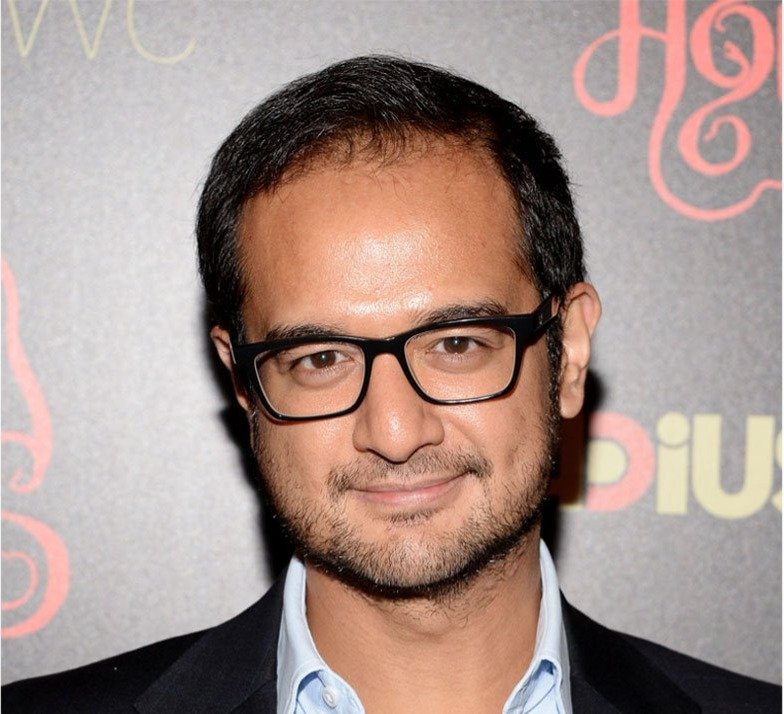

Riza Aziz, Prime Minister Najib’s stepson and friend of Jho Low. Co-founder of Hollywood film company Red Granite Pictures.. Ben Gabbe / FilmMagic / Getty

Jasmine Loo, 1MDB’s General Counsel and Executive Director of Group Strategy

Khadem al-Qubaisi, Chairman of Aabar, a subsidiary of the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund. Duncan Chard / Bloomberg via Getty Images

Mohamed al-Husseiny, CEO of Aabar, a subsidiary of the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund. David Cannon / Getty Images for Laureus

Eric Tan, A Malaysian and associate of Jho Low, who served as a proxy for Low in numerous financial transactions

How the scheme worked

In total, $4.5 billion was allegedly embezzled from the Malaysian government-owned 1MDB. ZUMA Press, Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

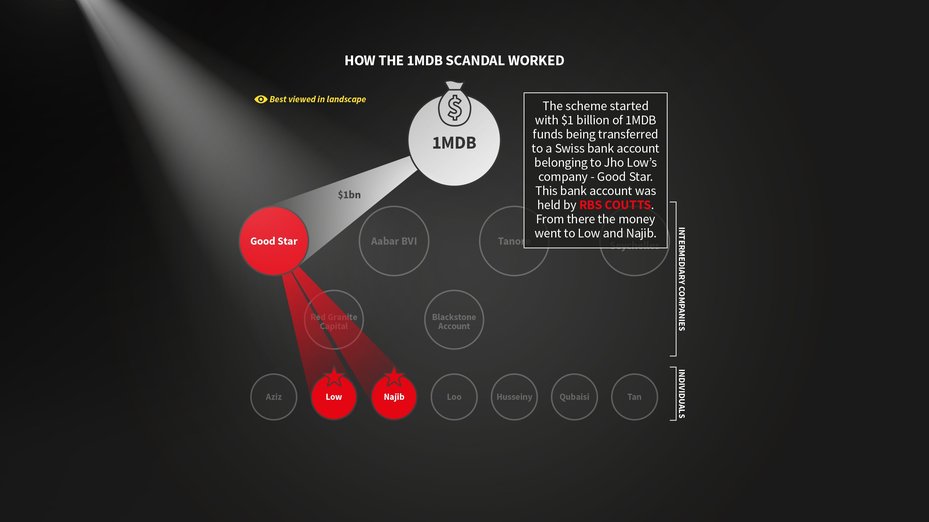

The scheme relied on close collaboration between those within and with influence over 1MDB, and those outside. The embezzlement revolved around those outside 1MDB creating companies that appeared to be investment opportunities for 1MDB.

1MDB then borrowed billions of dollars from investors, largely backed by the Malaysian government, to invest in these companies. Yet rather than 1MDB’s money being invested, it was instead passed through other companies the conspirators controlled to be used for their personal benefit.

The first phase of the scheme involved a joint venture between 1MDB and a Saudi oil company called Petrosaudi.[11] Low played a significant role in setting up the deal, organising a meeting between Petrosaudi’s co-founders and Najib on a yacht off the coast on Monaco in the summer of 2009.[12]

In September, Low emailed his family saying “Just closed the deal with petrosaudi. Looks like we may have hit a goldmin[e].”[13]

The deal was a goldmine for Low. Under the guise of this joint venture, more than $1 billion of 1MDB funds were instead transferred to a Swiss bank account belonging to a company he owned called Good Star.[14] 1MDB had borrowed much of this billion dollars from investors and these loans were guaranteed by the Malaysian government.14

As with the subsequent phases, this money was embezzled for the personal benefit of Low and other conspirators and never invested for the benefit of 1MDB or the Malaysian people, the DoJ says.

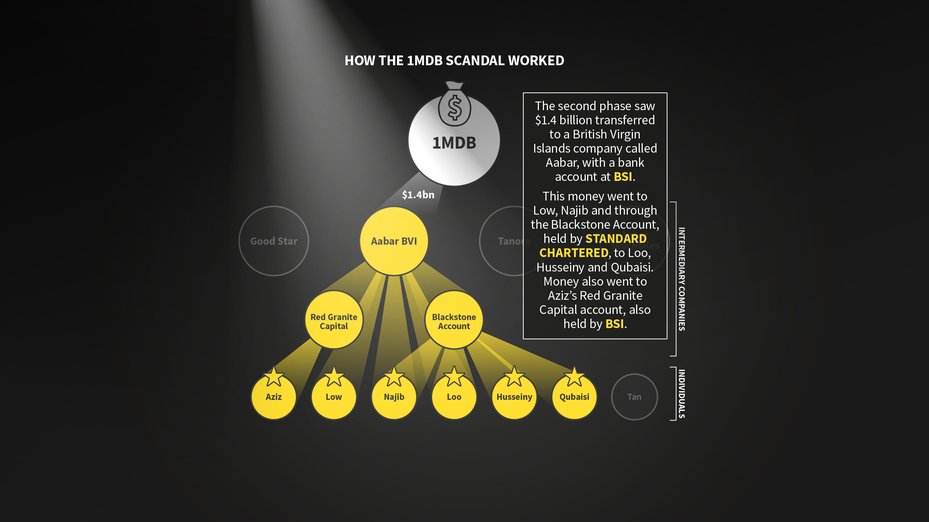

The second and third stages of the scheme involved another set of joint ventures, this time with Aabar, a subsidiary of the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund.[16]

To fund these joint ventures 1MDB borrowed $6.5 billion from investors, the majority of which was ultimately backed by the Malaysian government.[17] Of this, $2.6 billion was shifted out of 1MDB to the conspirators’ bank accounts.[18]

In the second phase, more than a billion dollars went into a Swiss bank account of a company called Aabar.

However, this was not the real Aabar, it was a company registered in the British Virgin Islands with the same name, which the DoJ refers to as "Aabar-BVI".[19] Qubaisi and Husseiny, officials at Aabar, set up this company with the intention of making it appear as if it was related to the real Aabar – yet nothing could be further from the truth.[20]

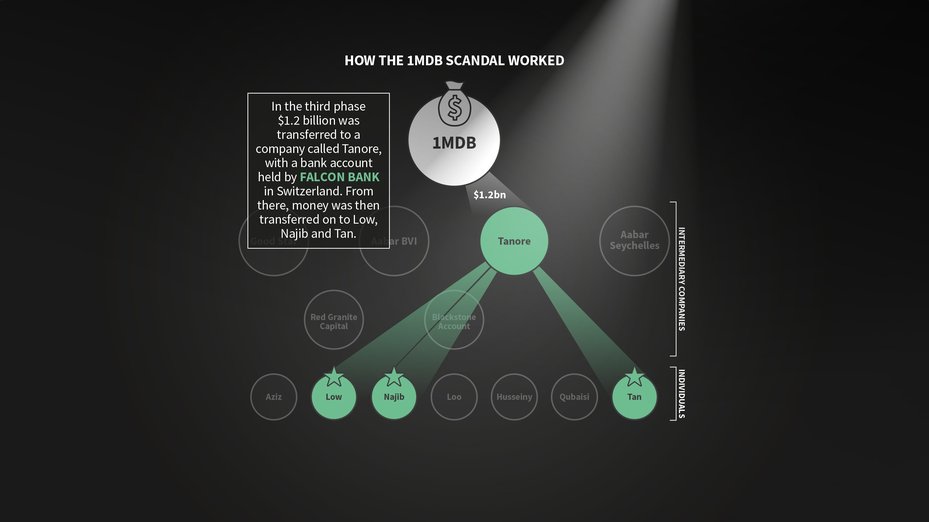

In the third phase, more than a billion dollars more was diverted to a Singapore company bank account owned by an associate of Low called Eric Tan.[21]

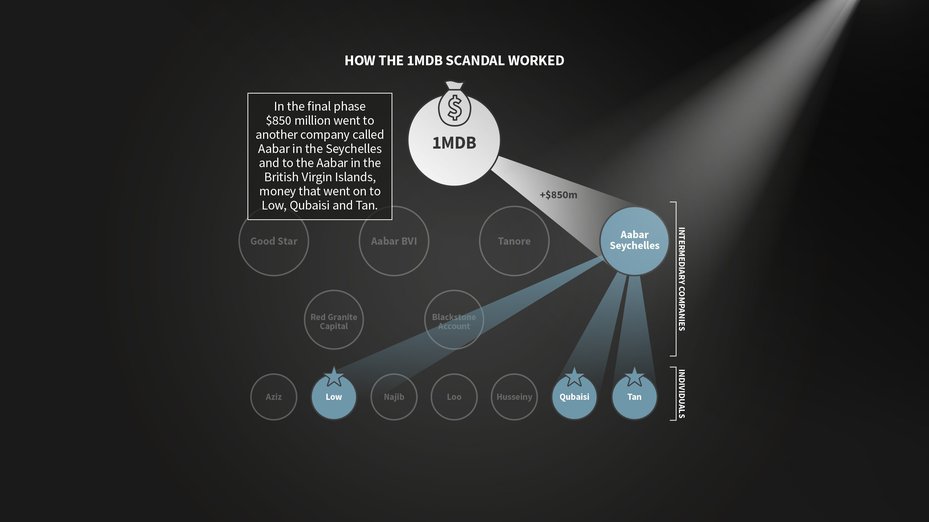

The DoJ's case is that the fourth phase of scheme intended, at least in part, to cover up the huge losses 1MDB had made as its money embezzled in the earlier stages of the scheme had been used to fund lavish lifestyles rather than business investments.[22]

To do this 1MDB borrowed more than a billion dollars, which it cycled repeatedly through its accounts and a series of opaque offshore companies and investment funds.[23]

Through these transfers it created the appearance of money flowing into 1MDB from its investments. Yet beneath this appearance, $850 million of this was diverted to Aabar-BVI and another Aabar copy registered in the Seychelles, "Aabar-Seychelles".[24][22]

Payouts and purchases

Having taken billions from 1MDB, hundreds of millions of dollars went on to become apparently corrupt payments to those involved.

According to the DoJ, $730 million went to Najib in four separate payments between 2011 and 2014, of which $620 million was later returned to an account held by one of the other associates involved.[25] Millions more went to senior officials at 1MDB and the Chairman and CEO of Aabar, Qubaisi and Husseiny.[26]

Part of the money returned from Najib’s account was transferred through other accounts to purchase a $27 million necklace for Najib’s wife. The necklace, a 22-carat pink diamond pendant, was specially commissioned after Low and Najib’s wife met with a high-end jeweller in Monaco aboard a chartered luxury yacht.[27]

Jho Low’s yacht, The Equanimity, bought with $250 million of 1MDB funds. Simon Dawson / Bloomberg via Getty Images

The assets the DoJ is attempting to seize demonstrates the scale of the spending of money from 1MDB by those involved. This includes business shares or assets worth over $450 million, 12 properties collectively worth over $350 million, a $35 million private jet and nearly $10 million of jewellery.[28]

Arguably the most prestigious of Low’s purchases with these laundered funds was his $250 million, 300ft yacht, the Equanimity.

The DoJ described it as a luxury mega-yacht capable of carrying up to twenty-six guests and up to thirty-three crew members and includes a helicopter landing pad, an on-board gymnasium, a cinema, a massage room, a sauna, a steam room, an experiential shower, and a plunge pool.[29]

Low partnered with the estate of Michael Jackson and Sony Music to buy EMI, the world’s third largest music publishing company. Kevork Djansezian-Pool / Global Witness

Low didn’t just use the funds for an extravagant lifestyle. He used funds from 1MDB to purchase a $100 million stake, alongside Sony Music and the estate of Michael Jackson, in EMI, the world’s third largest music publishing company. Its catalogue includes artists such as The Beatles, Pink Floyd and The Beach Boys.[30]

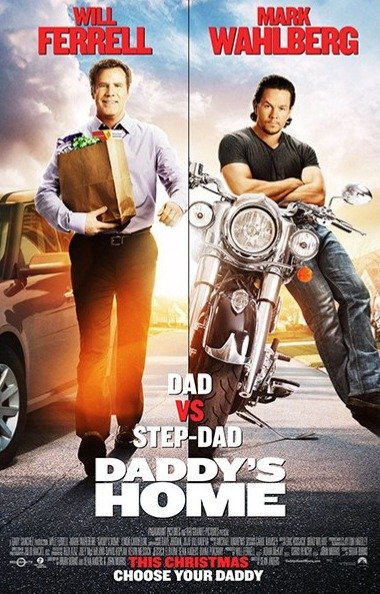

The DoJ also claims that the films The Wolf of Wall Street, Dumb and Dumber To and Daddy’s Home were financed with tens of millions of dollars of 1MDB funds funnelled through Aziz’s film production company.[31]

Funds from 1MDB were also used to purchase around $137 million worth of art, including Dustheads by Jean-Michel Basquiat for $48 million, La Maison de Vincent a Arles by Van Gogh for $5.5 million and Yellow and Blue by Mark Rothko, worth around $46 million.[32]

Leondardo DiCaprio in The Wolf of Wall Street, which was financed with money taken from 1MDB.Paramount Pictures / courtesy Everett Collection / Mary Evans

Paying the price

The full impacts of the alleged corruption at 1MDB on the Malaysian people are yet to be fully felt, as 1MDB is still in the process of trying to resolve the financial fall-out. Yet the risks to Malaysia are huge.

If 1MBD fails to repay its debts, which is likely given the scale of the alleged embezzlement, it is estimated that the Malaysian government would have to repay nearly $5 billion.32 Including interest, this would be more than the annual government budget for healthcare.33

The impacts of this case aren’t purely financial; it has also undermined Malaysia’s democracy.

The investigative site Sarawak Report has disclosed documents showing that Najib gave around $140 million to local branches of his ruling party in the run up to the 2013 election, believed to be an attempt to buy personal loyalty from within his own party. These payments came from the same personal bank accounts that had received money embezzled from 1MDB.34

The fall-out from the scandal has also led to government crackdowns on the media and opposition politicians. The Malaysian government suspended two of the country’s leading financial newspapers over their reporting of the 1MDB case.

Two opposition lawmakers also said that they had been issued travel bans by the government in connection with investigations into corruption at 1MDB.35

Protesters holds up clown-faced caricatures of Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak and his wife during a protest over the 1MDB scandal in Kuala Lumpur in August 2016. Rohd Rasfan / AFP/Getty Images

The FBI has also cited potentially retaliatory or threatening acts linked to its 1MDB investigation. These included a senior Malaysian politician being arrested and charged with attempting to overthrow the government after arranging to talk to the FBI and the arrests of three Malaysian law enforcement officials investigating 1MDB.36

While resisting outside scrutiny, there has been a whitewash by Malaysian authorities. The Anti-Corruption Commission cleared Prime Minister Najib of wrongdoing and the Attorney General repeatedly dismissed calls for criminal proceedings to be launched, though re-opened the investigation into 1MDB in late 2017.37

Prime Minister Najib and 1MDB have consistently denied all of the allegations against them.

Low and his family are contesting the DoJ asset freezing order, with Low issuing a statement saying the US government was continuing “inappropriate efforts to seize assets despite not having proven that any improprieties have occurred.”38

According to papers filed by his lawyer, Aziz “is neither alleged to have participated in any transactions involving 1MDB nor even to have knowledge of any transactions involving 1MDB – let alone knowledge of any supposed misappropriation."

The filing stated that “Mr Aziz plainly did not engage in a money laundering transaction or any other offense."39

In March 2018, Aziz’s film production company agreed to pay the US government $60 million to settle the case. The settlement states that the payment should not be understood as “an admission of wrongdoing or liability on the part of Red Granite [Aziz’s company].”40

PetroSaudi has denied any wrongdoing and rejected any claims of involvement in misappropriation of funds from 1MDB.41

DiCaprio and Kerr are both co-operating with the investigation and have returned the gifts they received.42

Banks: Stashing the cash

What banks are supposed to do

Banks are not supposed to handle criminal cash, and an international anti-money laundering system has been developed to achieve this.

Internationally, standards are set by a little-known intergovernmental body called the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), with governments then expected to place requirements on banks and other professionals to prevent them from handling dirty money.

This is how it should work; banks are supposed to know who their customers are when they open an account and know who the owners and controllers of the businesses they provide accounts for are.

Banks should monitor transactions to ensure that these are consistent with the information they were given when the account was opened. If they spot a suspicious transaction, they should report it to national regulators and either not perform the transaction or close the account.[44]

This whole process is known as customer due diligence.

Banks are also expected to take greater steps to address the corruption risks posed by senior public officials, such as government ministers or senior civil servants.

These officials are known as politically exposed persons (PEPs) as they present a greater risk of either being bribed or embezzling public funds because of their high-ranking positions.

Banks are required to identify if their customers is a PEP and then conduct enhanced monitoring of the account to look for suspicious transactions.

These measures should also be applied to their family members and close associates.[45]

This is how the system is supposed to work. Yet in this case, a group of individuals were able to shift billions of dollars out of a government-owned entity into their own bank accounts.

RBS Coutts

Jho Low bought a $35 million Bombardier private jet with money from the Good Star account.. Antony Nettle / Alamy Stock Photo

The first billion dollars

The first bank to handle money embezzled out of 1MDB was RBS Coutts, which at that time was ultimately majority-owned by the UK government.

According to the DoJ, it handled more than a billion dollars in suspect cash linked to the first phase of the scheme, the joint venture with Petrosaudi.[46]

At the outset, 1MDB was supposed to invest $1 billion in the joint venture.[47] Instead, 1MDB instructed their bank, Deutsche Bank, to make two transfers for $300 million and $700 million.

These instructions only included the account numbers, and did not include the names of the accounts or their beneficiaries.[48]

The bank account receiving the $300 million did belong to the joint venture.[49] However, the bank account set to receive the $700 million, held by RBS Coutts in Switzerland, actually belonged to a Seychelles company called Good Star, which Low owned.[50]

RBS Coutts knew that Low was the beneficial owner of the Good Star account as he had declared this when he opened it.[51] Clearly RBS Coutts had questions about the proposed payment from a government-owned company into this account.

RBS Coutts officials met with him to ask for more details on the proposed payment and Low provided them with a copy of an agreement, signed by 1MDB officials, fraudulently claiming that the transfer was an investment by 1MDB.[52]

RBS Coutts compliance staff also emailed Deutsche Bank requesting the name of the beneficiary of the funds, stating that they could not credit the Good Star account without it.[53]

In response to RBS Coutts’ request, 1MDB officials told Deutsche Bank that the beneficiary was not Petrosaudi, as they had previously said, but was Good Star; fraudulently claiming it was owned by Petrosaudi.[54]

Deutsche Bank then included the account name – Good Star – in the transfer details and the payment was released to the account at RBS Coutts.[55]

Even after this payment had been processed “employees at [RBS Coutts] continued to have concerns about the size of, and justification for, the $700 million wire from a state-owned entity”, according to the DoJ, and requested further confirmation from Low and 1MDB.

The Executive Director of 1MDB confirmed to RBS Coutts the false information that Low had already given the bank.[56]

It is clear that the payments and justifications given were not instantly convincing to RBS Coutts.

In an internal email, a member of the compliance team said: “It would be the first time in my career that I would see a case where [in] an agreement over the amount of $600 million or so the role of the parties has been confused.”

RBS Coutts’ legal unit even spoke of the risk of a “total fabrication.”[57]

Just a few months later, Low changed the explanation for the transfer, producing new fraudulent documents claiming the transfer was in fact a loan, rather than an investment.[58]

The corruption risks for these huge transfers from a state owned entity were clear, yet RBS Coutts went on to credit a further $330 million in transfers from 1MDB into the Good Star account.[59]

A lucrative relationship

The Singapore banking regulator fined RBS Coutts $1.7 million (2.4 million Singapore dollars) for breaches of anti-money laundering rules over 1MDB for failures in its handling of relationships with PEPs, though it placed the blame on “the result of actions or omissions of certain officers” rather than any wider systemic failings.[60]

The Swiss banking regulator fined RBS Coutts $6.6 million (6.5 million Swiss francs), finding that “those responsible failed to follow up on these clear causes for concern” and instead chose to “continue with the lucrative business relationships”.[61]

Swiss regulators referred RBS Coutts’ involvement to the UK banking regulator, as RBS owned it at that time, though UK regulators or law enforcement have not yet made any public statements on the case.[62]

RBS Coutts clearly saw reasons for suspicion, with huge sums of money being transferred from a state-owned company into Low’s account, with changing explanations for its origins.

Yet as the Swiss regulator found, they were all too willing to turn a blind eye to these suspicions and ended up breaking the rules in order to keep a highly profitable client.

RBS, which at that time owned RBS Coutts, responded to the regulators’ decisions stating that: “we regret any failings in our AML processes and the length of time it has taken to detect and resolve this issue.

"We will donate all profits from these accounts to an industry-wide AML program run by an independent educational body to help combat financial crime to ensure Singapore remains a financial center which adheres to the highest standards."

RBS added that RBS Coutts & Co had strengthened the policies and controls to prevent clients using its services to aid financial crime.[63]

BSI

Attack of the clones

BSI, a hundred-year-old Swiss Bank, would go even further than RBS Coutts to keep its clients happy, helping to plan parts of the fraud and even cover it up, violating anti-money laundering rules in multiple jurisdictions in providing accounts to many of the key actors in the scheme.

BSI’s first involvement came in the second phase of the scheme to embezzle money out of 1MDB through the joint venture with Aabar, the subsidiary of an Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund.

In 2012 the managing director of the sovereign wealth fund and chairman of Aabar, Khadem al-Qubaisi, and the CEO of Aabar, Mohamed al-Husseiny registered a company with exactly the same name – Aabar – in the British Virgin Islands.

When setting up this new company, which the DoJ refers to as "Aabar-BVI", Qubaisi and Husseiny claimed that the real Aabar was its sole shareholder.63

Aabar-BVI, however, was not owned by Aabar or the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund. Instead, Qubaisi and Husseiny took advantage of the fact that at that time the British Virgin Islands did not require evidence of a company’s shareholdings or beneficial ownership.65

This is a classic tool for money launderers, allowing them to disguise their ownership of the company, and therefore their role in the money flowing through that company.

The stars and producers of Dumb and Dumber 2 – allegedly financed with money from 1MDB. Amanda Edwards / WireImage

In this case, it meant that Qubaisi and Husseiny could set up a company that looked like the real Aabar, and hide the fact that they were the true owners and beneficiaries of that company.

The DoJ's filing shows Qubaisi and Husseiny opened an account at BSI in Switzerland, producing what they claimed was a "collaboration agreement", signed by 1MDB officials, and falsely claiming – against Swiss criminal forgery laws – that Aabar was the beneficial owner of the Aabar-BVI account.[66]

Having set up an account to mimic the real Aabar, $1.3 billion was transferred from 1MDB into the account.[67] Money from this account was transferred through various others to then go on to Qubaisi, Husseiny, Najib and 1MDB’s General Counsel, Jasmine Loo.[68]

The pattern of suspicious transactions continued. Two years later, the account was used to process the proceeds of a loan from Deutsche Bank to 1MDB, with $175 million transferred into the account.[69]

At this time, the account balance was less than $125,000 and had only been used to process one transaction in the previous two years.[70]

The poster for Daddy’s Home, also allegedly financed with funds from 1MDB.Paramount / courtesy Everett Collection / Mary Evans

According to the DoJ, the Aabar-BVI account showed “no activity consistent with the operation of a legitimate subsidiary of [Aabar]” and was almost solely to collect and distribute funds from 1MDB.[71]

The DoJ also states that setting up a clone company like this is “a technique commonly employed to lend the appearance of legitimacy to transactions that might otherwise be subject to additional scrutiny.”[72]

Given all of these risks, it is staggering that BSI continued processing these transactions, particularly given that Qubaisi and Husseiny were both PEPs due to their roles at the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund.

One of the reasons the alleged conspirators may have needed to make the fraud more complex, using a company to mimic the real Aabar, rather than just transferring the funds into Low’s Good Star account, was a change in international systems for bank transfers.

In November 2009, the organisation that facilitates inter-bank transfers, SWIFT, started requiring information on the beneficiary and sender in bank transfer instructions.[73]

By creating a company with the same name as a legitimate entity, the conspirators could provide a recipient name required for the wire transfers that would not raise suspicion.

These changes were introduced to improve anti-money laundering systems, yet this case shows how relying on the name of the account holder, rather than the accounts’ ultimate beneficial owner, is a major weakness in this system.

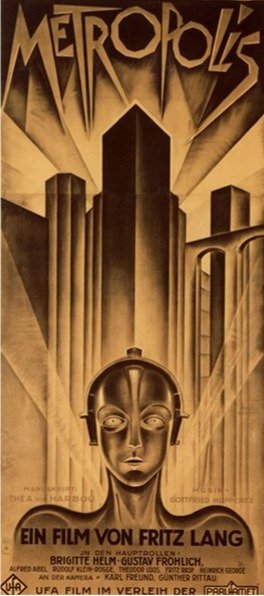

A rare original poster for the 1927 silent film Metropolis, bought by Aziz with $1.2 million from 1MDB. Moviestore collection Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Hollywood bound

As with the initial Good Star phase, the DoJ's evidence shows money was soon moved on from the Aabar-BVI account to go to the accomplices to the fraud.

$238 million was transferred into the account of Red Granite Capital, a British Virgin Islands company owned by Aziz, held by BSI.[74] To justify the transfer, BSI was told that Aabar-BVI had loaned the money to fund films including The Wolf of Wall Street.[75]

However, of the money that Red Granite Capital received, only $64 million was actually transferred to Aziz’s film production company.[76]

The vast majority of the money was instead used for Aziz’s personal benefit, the evidence suggests.

This included $94 million on luxury properties in New York, Beverly Hills and London and $5.5 million on film posters and memorabilia from just one company, including a rare original poster for the 1927 film Metropolis for $1.2 million.[77]

Aziz also used the funds he received to fund multi-million dollar gambling trips, including transferring $13 million to accounts at the Venetian Casino in Las Vegas that were used for gambling by the unlikely cast of Low, Aziz, Tan and DiCaprio.[78]

Despite the justification for the huge transfers into Aziz’s Red Granite Capital account being to finance films, there is no indication in the DoJ’s evidence that BSI took action to stop the flow of money when the majority was clearly being used for Aziz’s personal benefit.

This is of particular concern given that his account should have been subject to enhanced monitoring, as Aziz is Najib’s stepson, and therefore should be treated as the family member of a PEP.

Family tradition

Jho Low in New York in October 2014. Dimitrios Kambouris / Getty Images for Gabrielle's Angel Foundation

BSI also held one of Low’s personal accounts that had received large amounts of money from the Good Star account.[79]

After allegations about Good Star and 1MDB first surfaced in 2015, BSI officials contacted Low to ask about the flow of funds from Good Star to his account at BSI.[80]

Low falsely claimed to BSI that Good Star was owned by Petrosaudi, backed by a fraudulent letter from Petrosaudi’s CEO. This was despite the fact that he had previously told BSI multiple times that he owned the Good Star account.[81]

Compliance officers were also concerned that Low was moving large sums of money from his account through his father’s account to another account owned by Low to obscure the origin of the money in a flow of funds that BSI compliance officials deemed “not acceptable”.[82]

Low attempted to explain these flows as “family tradition” stating, “when good wealth creation is generated, as a matter of cultural respect and good fortune that arises from respect, we always give our parents the proceeds. This is part of our custom and culture.

"It is of course then up to the parents/elder to determine what to do with the funds and in this case, my father receives it as a token of gesture, respect and appreciation and decides to give it back for me.”[83]

To any expert in the field these explanations should seem almost comically implausible, yet despite this and his changing explanations for the ownership of the Good Star account, BSI continued to process Low’s transactions.[84]

A helping hand

These kind of money laundering failures are common for the big banks involved in corruption cases that Global Witness has looked at. Yet BSI officials went even further and actively helped Low and others carry out the fraud, according to the DoJ.

At one stage, BSI officials specifically marketed a series of investment funds to Low and 1MDB officials as vehicles to funnel money from 1MDB into the Tanore account held by Tan, one of Low’s associates.[85]

Later on, a banker at BSI Singapore also took on securing a fraudulent valuation of 1MDB’s investments to hide the scale of the embezzlement that had taken place (for more on this, see the section on auditors below).[86]

“The worst control lapses we have seen”

Swiss regulators effectively shut down BSI in 2016 because of “serious breaches” of regulations, ordering it be dissolved following a takeover by another bank.[87]

Swiss authorities also fined the bank $95 million (95 million Swiss francs) and launched criminal proceedings against it.[88]

The bank also had its licence revoked by Singapore’s banking regulator and fined $9.6 million (13 million Singapore dollars) for breaches including failure to conduct due diligence on high-risk accounts and monitor suspicious customer transactions.[89]

BSI Bank is the worst case of control lapses and gross misconduct that we have seen in the Singapore financial sector

Standard Chartered

The Venetian Casino in Las Vegas, which Low, Aziz, Tan and DiCaprio visited on a gambling trip. Chon Kit Leong / Alamy Stock Photo

Everyone gets paid

The vast majority of the money from the Aabar-BVI account, $1.1 billion, was transferred either directly or routed through overseas investment funds into an account held by Standard Chartered in Singapore for “Blackstone Asia Real Estate Partners”.[90]

This account was controlled by Tan, an associate of Low, who was on the trip to the Venetian Casino with him, DiCaprio and others.[91]

As with the Aabar-BVI account, “Blackstone Asia Real Estate Partners” sought to mimic the name of a legitimate business, in this case an affiliate of the New York listed investment firm Blackstone Group.

Malaysia's Prime Minister Najib Razak speaking to journalists in Kuala Lumpur in 2016 the day after the US DoJ asset seizure case was announced

As the DoJ points out this is commonly done “to lend the appearance of legitimacy to transactions that might otherwise be subject to additional scrutiny.”[92]

This Blackstone account was used to distribute embezzled 1MDB funds to key players in the deal, including payments to by Qubaisi, Husseiny, Najib and Loo.[93]

Again, this raises serious questions about what monitoring Standard Chartered undertook on the account, particularly given that the funds coming into the account would have appeared to have come from a subsidiary of Aabar, a subsidiary of the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund.

Yellow and Blue by Mark Rothko, bought with funds from the Tanore account. Mary Turner / Getty Images for Sotheby's

Numerous breaches

The Singapore banking regulator fined Standard Chartered, which held the Blackstone Account, $3.7 million (5.2 million Singapore dollars) for its anti-money laundering failures.

The regulator found “significant lapses in the bank’s customer due diligence measures and controls for ongoing monitoring” that it said were a result of inadequate policies, insufficient staff oversight, and a lack of staff awareness of money laundering risks.[94]

In its response to the fine, a Standard Chartered Bank spokesperson said that the bank "regrets" the breaches in transactions that occurred from 2010 to early 2013: "We reported the suspicious transactions, both before and at the time we exited the accounts in early 2013, and have been fully cooperating with the authorities investigating this matter.

"Standard Chartered has taken, and continues to take, remedial and disciplinary action where warranted and will continue to strengthen our controls, processes, and surveillance systems."[95]

The bank’s statement that it “exited the account” in early 2013, stands in contrast to the DoJ’s case that alleges that by February 2013 the account had already been emptied following the transfers to Qubaisi, Husseiny, Najib and Loo.[96]

Van Gogh’s Vincent A Arles, bought using $5.5 million of funds from 1MDB. The Print Collector / Getty Images

Falcon

More millions for Najib

The case of Falcon Bank shows what can happen when someone on the inside of a major fraud is also in charge of one the banks handling that money.

In the third phase of the scheme, more than $1.2 billion was transferred to an account at Falcon Bank, also owned by Tan.[97]

Loo, who should have been treated as a PEP due to her high profile role at 1MDB, also controlled the account, which was held in the name of a company called Tanore.[98]

The account’s first deposits were a series of transfers of hundreds of millions of dollars from 1MDB, routed through three investment funds.[99] Within days of this money entering the account, hundreds of millions were transferred to an account belonging to Najib.[100]

The account was also used to purchase over a hundred million dollars’ worth of art, including pieces by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Alexander Calder and Mark Rothko.[101]

As well as holding the Tanore account, Falcon also held the accounts for two of the 1MDB subsidiaries from which funds were transferred into the Aabar-BVI account.[102]

This is gonna get everybody in trouble

At that time, the real Aabar, the subsidiary of the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund, owned Falcon Bank.[103]

In his role as CEO of Aabar, Husseiny was also the Chairman of Falcon Bank and worked to convince compliance officials at the bank that the Tanore transactions were legitimate.[104]

In a conference call between Eduardo Leemann, Falcon’s CEO, its Singapore branch manager and Husseiny, Leemann said:

“Mohammed [Husseiny], the rest of the documentation, which our friend in Malaysia has delivered is absolutely ridiculous, between you and me … This is … gonna get everybody in trouble.

"This is done not professionally, unprepared, amateurish at best. The documentation they’re sending me is a joke, between you and me, Mohammed, it’s a joke!

"This is something, how can you send hundreds of millions of dollars with documentation, you know, nine million here, twenty million there, no signatures on the bill, it’s kind of cut and paste… I mean it’s ridiculous! …

"You’re now talking to Jho [Low], and tell him, look, you either, within the next, you know, six hours produce documentation, which my compliance people can live with, or we have a huge problem.”[105]

Low bought Monet’s Saint-Georges Majeur for $35 million using money from 1MDB.. Ben Pruchnie / Getty Images

Leemann also called Low, stating:

“if anybody just looks at it remotely, this is going to be all over the place. Receiving banks, wiring, and, and, what I try to do here is protect Eric and anybody in the room because if, if any other bank just make “peep!” and this gets reported, … we are gonna have a huge problem.”[106]

According to the DoJ, Falcon continued processing the transactions out of the account, in part because Husseiny as the Chairman vouched for the legitimacy of the transactions despite the concerns of the CEO and compliance staff.[107]

Everybody's in trouble

As Falcon’s CEO predicted, there was trouble – the bank lost its Singapore banking licence in October 2016 and was fined $3.1 million (4.3 million Singapore dollars) for breaching anti-money laundering rules.[108]

An inspection by Singapore regulators in 2015 found a large number of serious anti-money laundering failures and improper conduct by management in Switzerland and its Singapore branch.

These included failing to guard against conflicts of interest over a customer linked to Husseiny, stating that he misled and influenced the Singapore branch into processing the “unusually large transactions” despite “multiple red flags”.[109]

Singapore regulators found that managers in the Singapore branch had interfered in the work of the compliance department and that the bank demonstrated a persistent and severe lack of understanding of anti-money laundering requirements.[110]

Swiss regulators fined Falcon $2.5 million (2.5 million Swiss francs) in illegally generated profits, banned it from entering into relationships with foreign PEPs for three years, and threatened it with having its banking licenced revoked in the event of any future breaches.

It accused Falcon of repeatedly failing to properly investigate high-risk transactions and business relationships, specifically those with PEPs.[111]

Low bought Monet’s Nympheas for $57.5 million using money from 1MDB. Ben Pruchnie / Getty Images

In relation to the $1.2 billion that flowed through one of Falcon’s accounts, which matches the description of Tan’s Tanore account, the regulator found that the bank did not verify how he was able to access or acquire these funds, despite it being “clearly” different from the information he gave the bank when he opened the account.[112]

In relation to the hundreds of millions flowing to and from Najib’s accounts, the regulator found that Falcon failed to adequately investigate the background to these transactions “despite conflicting evidence”.[113]

Swiss federal prosecutors also launched criminal proceedings against the bank in October 2016 for failing to prevent money laundering.[114]

While the bank is now starting to pay the price for these dramatic failings, the case of Falcon Bank shows just how much damage can be done when someone alleged to be involved in a multi-billion-dollar embezzlement scheme is also in charge of a bank.

A failure to obey the rules

What this case shows is that this was not a problem of inadequate regulations but a failure of banks to follow those rules. RBS Coutts, BSI, Standard Chartered and Falcon were all fined for violating money launderings rules in multiple jurisdictions.

The banks were simply not putting in place the money laundering controls that they were required to do. Either their systems failed to spot the clear money laundering risks, or the banks were willing to ignore the risks they saw.

Nigerian dictator Sani Abacha, who shifted over $1.3 billion of money looted from the Nigerian government through major UK banks.. Fethi Belaid / AFP/Getty Images

This is not the first time that major banks have handled corrupt cash, as Global Witness has reported many times before. Some of the highest profile cases, highlighted in our 2015 report Banks and Dirty Money, include:

- 23 UK banks were found to have handled over $1.3 billion looted from Nigeria by the then dictator Sani Abacha.

- Riggs Bank in the US collapsed in 2005 when it was found to have “turned a blind eye” to evidence of corruption by holding up to $700 million for President Obiang of Equatorial Guinea, his family and officials.

- Barclays, RBS, HSBC, NatWest and UBS accepted millions of pounds from corrupt Nigerian state governors.

- HSBC and two other Swiss private banks handled money from associates of the corrupt former Tunisian leader Ben Ali.[115]

In my view, that's one of the failings of our current regime globally –that people continued to do wrong things because they are not being held personally liable and responsible

President Obiang of Equatorial Guinea and his family and officials held up to $700 million in Riggs Bank in the US.Flickr: Embassy of Equatorial Guinea

Improving the system

While there were rules in place to prevent this from happening, there is still more that could be done to improve the current anti-money laundering system.

One major problem is that many banks’ transaction monitoring systems are often backwards looking, meaning that they are only able to identify suspicious transactions long after the money has changed hands.

Looking at historical data can doubtlessly help spot patterns that may emerge over time, but this should be no substitute for having live systems designed to spot and stop suspicious transactions before the money is ever transferred.

Another major problem is that banks frequently report transactions as suspicious to national regulators and process the transaction anyway.

This is because in many jurisdictions, reporting a suspicious transaction gives the institution a defence against money laundering offences.

This system allows banks a legal defence to continue handling suspect cash, while failing to provide regulators with information that would be useful enough to be able to investigate.

Much more needs to be done to stop banks processing transactions when they do have suspicions, and to improve the quality of the reports they are required to make.

The wrong incentives

Yak Yew Chee, a former BSI banker in Singapore and one of the few financial professionals involved in the case to face criminal charges. Roslan Rahman / AFP/Getty Images

In the end, this is a problem of incentives. There are regulations to require banks not to handle dirty cash, yet they do, time and again. Banks could put in place systems that would be far more effective, yet they do not.

One reason why they don’t could be because it is not currently worth their while. In this case, regulators fined the banks involved $122 million for handling $4.5 billion of suspicious funds.[116]

The risks of getting caught and the fines they expect to face simply do not outweigh the costs of turning away potentially lucrative business.

Larger banking fines could help prevent them just being treated as the cost of doing business, yet this alone is unlikely to truly re-shape banks’ behaviour. This is because fines don’t affect the bank’s management who failed to prevent the bank handling dirty money.

To change banks’ practices, the incentives for those at the top need to change by holding senior managers accountable for their bank’s actions. Most of the time, this does not happen.[117]

In this respect, the actions of Singapore regulators and law enforcement in this case are a rare example of good practice, with bank staff involved facing personal criminal prosecutions for their actions.

Three BSI bankers were found guilty of criminal offences in Singapore, including forging documents, failing to disclose suspicious transactions, deception and money laundering offences.

Two received small fines and brief jail sentences, with the third sentenced to four and a half years in prison and a lifetime ban by the Malaysian financial regulator for his role in the case.[118]

Falcon’s Singapore branch manager pleaded guilty to a range of charges including failing to report suspicious transactions and was sentenced to 28 weeks in jail and fined $89,000 (89,000 Singapore dollars).[119]

Prosecuting those responsible is a vital step, yet these prosecutions are only for those who were involved in the most flagrant breaches of anti-money laundering rules and only for middle managers, not the bank’s executives.

A bank’s senior executives are responsible for the whole bank’s actions and have the responsibility to make sure it has systems in place to prevent it from handling dirty money.

Rules need to be changed to make it easier to hold senior banking executives personally liable for their banks failure to prevent them handling criminal funds.

Billions for me, millions for you

Did Goldman Sachs know?

Tim Leissner was Goldman Sachs South East Asia Chairman and managed the bank’s relationship with 1MDB.. Araya Diaz / Getty Images for The Weinstein Company

Banks weren’t just involved in the 1MDB case by providing accounts. They also raised billions of dollars in loans to 1MDB that were fraudulently taken by Low and his associates.

Goldman Sachs did the biggest part of this business. Over the course of 12 months in 2012 and 2013, Goldman Sachs raised $6.5 billion in three sets of bond offerings for 1MDB.[120] An astonishing $2.6 billion of this was allegedly embezzled into the Aabar-BVI and Tanore accounts, 40% of the total raised.[121]

According to the DoJ, the documents provided to prospective investors by Goldman Sachs “contained misleading statements and omitted material facts necessary to make its representations not misleading."[122] This included not disclosing that funds would be transferred to Aabar-BVI, and on to individuals including Husseiny, Qubaisi, 1MDB officials and Najib.[123]

All of the bond offerings produced by Goldman Sachs were vague about how the funds would be used. The first stated that funds could be used for “other corporate purposes”, and the third that the joint venture to be funded “does not have any specific investment, merger, stock exchange, asset acquisition, reorganization, or other business combination under consideration or contemplation.”[124]

While the lack of a clear plan for what to do with the money raised should have been a concern to investors, the cost of Goldman Sachs’ services should have been a concern to 1MDB. Goldman Sachs earned nearly $600 million in fees and commissions for issuing the bonds, 9% of the total raised.[125] The usual fee for such a deal would typically be around $1 million for each round, 0.5% of the fee Goldman earned.[126]

In order to meet 1MDB’s objectives of raising the funds as quickly as possible, Goldman agreed to buy the bonds from 1MDB for later sale to investors. This meant 1MDB could raise the money almost instantly, but Goldman took on greater risk while it held the bonds. Goldman later said this higher risk justified the high fees they charged.[127]

The combination of Goldman’s unusually high fees and the speed with which the money was shifted out of 1MDB raises questions about whether Goldman was aware, or should have been aware, of the plans to siphon off the money. For example in the case of the third bond, even before the bonds were issued, 1MDB officials and Low had already arranged to move funds through the overseas investment funds to the Tanore account.[128]

This is not the first time Goldman Sachs has used bonds to raise funds in questionable circumstances in Malaysia. The year before, Global Witness lambasted the investment bank for appearing to ignore corruption risks and conflicts of interest in order to underwrite $1.6 billion in bonds for the Government of Sarawak, a Malaysian state on the island of Borneo.[129]

The Wall Street Journal has reported that the DoJ, Federal Reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission, New York State’s Department of Financial Services and Singapore regulators are all examining aspects of Goldman’s role in the 1MDB case, including whether it had any reason to suspect funds would be misused.[130]

In response to the allegations, Goldman stated that it had no way of knowing the funds would be embezzled and that they have “found no evidence showing any involvement by Jho Low in the 1MDB bond transactions”.[131] This statement appears to contradict emails discussing the bond offerings quoted in the DoJ case in which a senior Goldman director refers to Low as the “the 1MDB Operator or intermediary in Malaysia.”[132]

Lawyers: No checks required

Banks are not the only institutions that provide accounts to hold and move money around, lawyers do too.

Lawyers in the US are not required to do customer due diligence on their clients in the same way that banks do and don’t have to investigate client conduct unless they believe their client is engaging in illegal activity.[133]

When lawyers hold accounts for their clients, the banks that hold these accounts in turn only have to do checks on the law firm, not its clients. So, neither the bank nor the law firm are required to do checks on the clients using these accounts.

The result is “a way of getting money into the US system without going through the anti-money-laundering safeguards,” said Elise Bean, former chief counsel to a Senate subcommittee that investigated money laundering and corruption, describing it as “a pretty darn big loophole.”[134]

$12 million was transferred from the Shearman and Sterling client account to Caesars Palace casino in Las Vegas. Harald Schmidt / Alamy Stock Photo

Through the loophole

Low used this loophole to shift approximately $368 million from his Good Star account in Switzerland into the US, through the law firm Shearman and Sterling’s client account, the DoJ allege.[135]

Low held funds in the client account for over a year, and used it to purchase luxury properties including L’Ermitage, the Park Laurel Condominium and the Time Warner Penthouse, as well as his private jet.[136]

Low’s use of the client account was not restricted to high value purchases; he also used it for gambling expenses and renting private yachts and jets, including transferring $25 million to accounts at Caesars Palace and the Venetian Casino in Las Vegas and spending over $4 million on private jet rental.[137]

Aziz also used a Shearman & Sterling client account to buy three properties in New York, Beverly Hills and London worth $94 million using funds from 1MDB.[138] Low used another firm’s client account, DLA Piper, to buy a $200 million stake in the Park Lane Hotel in New York.[139]

One New York attorney described the size of the deposits as unusually “ridiculous”, while other attorneys were reported saying the huge deposits should have raised suspicions.[0]

This isn’t the first time that US lawyer client accounts have been used to shift corrupt funds into the US. Teodorin Obiang, son of the President of Equatorial Guinea, shifted millions of dollars of his country’s money into the US through lawyers’ client accounts and used these to pay his personal bills and expenses.[140]

Unusually ridiculous

The Park Lane Hotel in New York, bought by Low for $200 million using funds from DLA Piper’s client account.Park Lane Hotel New York/ Website

There is no law requiring US lawyers to conduct due diligence and therefore, unlike the banks involved, there is no suggestion either Shearman and Sterling or DLA Piper broke anti-money laundering rules.

However, the American Bar Association’s voluntary code of practice recommends that “any time lawyers ‘touch the money’ they should satisfy themselves as to the bona fides of the sources and ownership of the funds in some manner."[141]

Given the highly questionable nature of the funds moving through these accounts, this raises questions about whether these firms did follow the association’s voluntary code of practice and what if any checks they did on the funds moving through their accounts.

In response to the allegations in the DoJ’s case, Shearman & Sterling issued a statement saying that it “did not know and had no reason to believe that any funds transferred to Shearman & Sterling were the proceeds of unlawful activity. It is common practice for law firms to receive substantial funds from clients for disbursement in connection with real estate closings, as was the case here.”[142]

DLA Piper stated, “As a large, global law firm, we are routinely involved in cross-border transactions and are occasionally called upon to hold client funds needed for the transaction. When we do, we have policies and procedures in place to ensure that we are fully compliant with all legal and ethical obligations and standards.”[143]

Closing this “serious gap”

The problems of US lawyers not having to do anti-money laundering checks are not restricted to client accounts. An undercover investigation by Global Witness in 2016 exposed the role lawyers can play in advising how to move suspect funds into the US.

Wearing a hidden camera, an investigator posing as an adviser to a foreign government minister met with 13 New York law firms.

He asked the lawyers how to anonymously move large sums of money that should have raised suspicions of corruption. In all but one case, the lawyers provided suggestions on how the minister might get the money into the US without detection.[144]

FATF, the international anti-money laundering standard setting body, highlighted these risks in its 2016 assessment of the US. It found that lawyers were not applying basic or enhanced due diligence processes, describing this as a “serious gap”.[145]

It went on to note that it is also was not clear whether lawyers were complying with the ABA’s voluntary guidelines, as they are not enforceable, and recommended that anti-money laundering rules be imposed on lawyers “as a matter of priority”.[146]

In response to the issues raised by Global Witness’ investigation and the FATF recommendation, the American Bar Association has reportedly prepared a new ‘Model Rule of Professional Conduct’ that would impose basic customer due diligence requirements on lawyers.[147]

If adopted, this would mean that lawyers who did not conduct anti-money laundering checks on their client accounts could be subject to disciplinary action – unlike the current voluntary code of conduct.

While such efforts to improve standards within the industry could be an important step forwards, this would leave responsibility for compliance and enforcement in the hands of state bar associations.[148]

The question of whether they would actually do this is an issue that is “unresolved” according to one member of the ABA Task Force that developed the new proposed Model Rule.[149]

In addition, the Model Rule is only a model, with no requirement that state bar associations adopt its recommendations into their rules.

The only way to ensure that this "darn big loophole" is closed is through federal regulation, with the US passing legislation requiring lawyers to conduct these anti-money laundering checks on their clients that is then enforced by US regulators.

Where were the Auditors?

The Petrosaudi Saturn, one of the two oil drilling ships that were the only remaining assets from the original Petrosaudi joint venture. John Sirre / MarineTraffic.com

During the time that billions of dollars were being drained out of 1MDB, three of the ‘Big Four’ accountancy firms audited its financial statements, signing off their accounts without any apparent concerns from 2011 to 2014.

Having a public seal of approval from these global firms provided 1MDB with an air of respectability and could have lessened any outside concerns about its financial mismanagement during this time.

EY

The first warning signs

EY, formerly Ernst & Young, was the first of 1MDB’s ‘Big Four’ auditors, having been appointed to its predecessor in March 2009. However its contract with 1MDB was terminated in September 2010 before 1MDB submitted its 2010 accounts.[150]

The problems began when EY attempted to assess the value of the original joint venture with Petrosaudi, requesting information about the due diligence 1MDB had undertaken and the joint venture’s assets and ownership.

This would have been a significant problem for those involved in the fraud, as $1 billion that should have gone to the joint venture had instead gone to Low’s Good Star account.

Through this audit process EY did not find any documents that showed the actual ownership of the joint venture, or information about the assets it held.[151] EY raised its concerns about the lack of information about the joint venture to 1MDB’s management. As a result of raising their concerns, 1MDB’s board terminated their contract.[152]

KPMG verified 1MDB’s 2011 and 2012 accounts as “clean” and without any cause for concern. B Christopher / Alamy Stock Photo

KPMG

Covering their tracks

KPMG was appointed to immediately replace EY in September 2010, and allegedly rushed the audit of 1MDB’s 2010 accounts, signing them off just one month after they were appointed.[153] KPMG went on to verify 1MDB’s 2011 and 2012 accounts as “clean” and without any cause for concern.[154]

At the time that KPMG was appointed, the DoJ allege that Low and 1MDB officials were trying to inflate the reported value of 1MDB’s investment in the joint venture with Petrosaudi, with the aim of hiding the fact that $1 billion of its investment had gone to Good Star and not to the joint venture.

To achieve this they restructured the investment multiple times, eventually converting into an opaque asset which could not easily be valued or verified by auditors.[155]

To achieve this, 1MDB set up a subsidiary called Brazen Sky to hold units in an investment firm called Bridge Global Fund, based in the Cayman Islands, with its bank account held by BSI in Singapore.[156]

While the Bridge Global Fund may have sounded impressive, the main assets it held were shares in a loss-making company operating two oil drilling ships in Venezuelan waters, the only remaining assets from the original Petrosaudi joint venture.[157]

Deloitte were appointed to replace KPMG and signed off 1MDB’s 2013 and 2014 accounts as “clean” and without any cause for concern.Credit Line Torontonian / Alamy Stock Photo

Time to Change the System

Leonardo DiCaprio in The Wolf of Wall Street.aramount Pictures / courtesy Everett Collection / Mary Evans

Despite it being more than eight years since the first money was allegedly embezzled out of 1MDB, many investigations into the role of banks in the case still remain unresolved.

The criminal charges brought by Swiss authorities against BSI and Falcon have not yet been brought to court and there has been no apparent conclusion to the reported investigations by almost every conceivable US authority into Goldman Sachs role in the case.

There is still no news as to whether the UK authorities are investigating the role of RBS and Standard Chartered head offices for the money laundering offences of their foreign branches.

All of these investigations need to be pursued effectively so that those responsible can be held to account.

Above all else, this case is a lesson in why more reform is urgently needed. The system did not work. A well-connected group managed to launder billions of dollars out of a government owned company. The people of Malaysia are now set to pay the price, both to cover 1MDB’s enormous debts and with the country’s democracy deeply damaged.

It was all too easy for those involved to use banks and lawyers to launder their funds. This is not new to Global Witness – it is a systemic problem that enables corruption on a vast scale all around the world. This corruption keeps dictators in power while keeping tens of millions of people in poverty.

This case demonstrates all too clearly why the rules need to change, making it harder to launder the proceeds of corruption, and making it harder to be corrupt in the first place. The two most urgent areas where action is needed are to address the risks posed by banks and lawyers.

For lawyers in the US the rules simply do not exist, leaving a vast hole in the anti-money laundering regime for one of the most attractive destinations in the world for corrupt cash.

For banks, the rules do already exist, yet they are routinely violated. The penalties for violating them are clearly not sufficient to change their behaviour, and those at the top of banks that handle dirty money need to be held to account.

Without this change, senior executives will continue to see fines for money laundering failures as just the cost of doing business, and a price worth paying for taking dirty cash.

All jurisdictions, but particularly those home to the headquarters of the world’s largest banks like the US and UK, should change the rules to ensure senior executives face serious fines, or jail, if the banks they lead flout the rules.

Unless the lessons of this case are learnt, it is only a matter of time until another group of enterprising and well-connected conspirators are able to defraud billions of dollars of government money for their own private gain.

Resource Library

The Real Wolves of Wall Street

Download ResourceEnd notes

-

Coutts: Singapore $1.7 million, Switzerland $6.6 million. BSI: Singapore $9.6 million, Switzerland $95 million. Standard Chartered: Singapore $3.7 million. Falcon: Singapore $3.1 million, Switzerland $2.5 million. http://www.mas.gov.sg/News-and-Publications/Media-Releases/2016/MAS-Imposes-Penalties-on-Standard-Chartered-Bank-and-Coutts-for-1MDB-Related-AML-Breaches.aspx; https://www.finma.ch/en/news/2017/02/20170202-mm-coutts/ ; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-05-24/singapore-orders-bsi-bank-to-shut-down-amid-1mdb-probe; http://www.mas.gov.sg/News-and-Publications/Media-Releases/2016/MAS-Imposes-Penalties-on-Standard-Chartered-Bank-and-Coutts-for-1MDB-Related-AML-Breaches.aspx; http://www.mas.gov.sg/News-and-Publications/Media-Releases/2016/MAS-Directs-Falcon-Bank-to-Cease-Operations-in-Singapore.aspx; https://www.finma.ch/en/news/2016/10/20161011-mm-falcon/