-

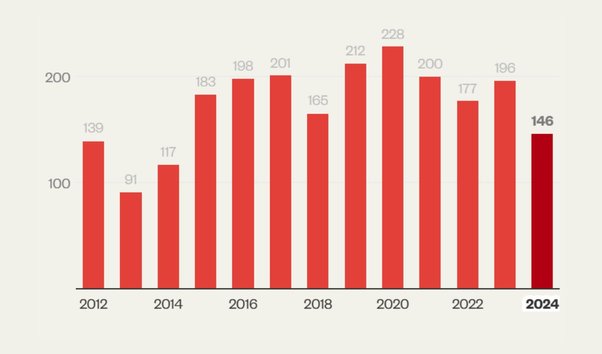

146

Defenders killed or disappeared

in 2024

-

2,253

Defenders killed or disappeared

since 2012

-

13

Years of documenting the violence

since 2012

Data snapshot: Counting every name

-

In numbers: Attacks against defenders since 2012

Explore our full dataset to find out where killings of defenders are occurring, which industries are responsible, and how this violence has changed over time

-

Documenting killings and disappearances of land and environmental defenders

How we work with partners to gather evidence, verify and document every time a land and environmental defender is killed or disappeared

-

Reporting on killings of Land and Environmental Defenders around the world

Since 2012, we have been raising awareness of killings and disappearances of land and environmental defenders through what is now an annual report

Criminalisation wave

-

The criminalisation of land and environmental defenders in Asia

In Asia, detentions and criminalisation of defenders are becoming increasingly common. Patterns in the types of laws being used are starting to emerge. Here we analyse these and look at how governments weaponise laws to detain defenders in the region

-

What is red-tagging, and how does it harm climate action?

Red-tagging – which falsely brands legitimate activists as terrorists – is used to silence land and environmental defenders online and IRL

-

Labour must end criminalisation of climate protesters

Five Just Stop Oil activists have been sentenced under the UK's draconian new protest laws criminalising civil disobedience. Will Labour reverse these laws?

Toxic platforms, broken planet

Land and environmental defenders are suffering from online abuse, with harassment reportedly leading to real-life violence and silencing those fighting to protect our planet

The time for change is now

The climate crisis is no longer an event on the horizon. It’s here, it’s now. Find out how you can support our work to tackle its root causes.

About us

Global Witness is an investigative, campaigning organisation that challenges the power of climate-wrecking companies, and stands with the people fighting back