The Deceivers

Update: On 30 July 2019, following a trial at criminal court C in Monrovia, Liberia, Judge Peter Gbeneweleh, acting as judge and jury, acquitted those on the indictment of all charges, it was reported. The defendants faced counts of economic sabotage, bribery, criminal facilitation, conspiracy and solicitation and had denied the charges.

As a spin bowler for the England cricket team Phil Edmonds won a reputation for deception and guile. He and his business partner Andrew Groves put those skills to use on the stock market, fleecing millions from investors as they carved out an African business empire with bribery and dirty tricks.

Philippe-Henri Edmonds was one of England’s most brilliant and controversial cricketers. Andrew Groves was the hard-talking son of a Zimbabwean policeman. Together they developed a near-infallible system for gaming the stock market.

A Global Witness investigation reveals how, with the help of secrecy laws in tax havens like the British Virgin Islands and the services of a top London lawyer, Edmonds and Groves crafted intricate insider deals to skim off millions of dollars of investors’ funds.

They floated a string of companies on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) – the barely regulated little brother of the London Stock Exchange – and set out to fill them with African assets, bribing officials as their agents intimidated rivals.

Hailed in the industry press as “resource rock stars with the Midas touch”, Edmonds and Groves had investors clamouring for a cut. US hedge fund Harbinger Capital Partners pumped $100 million into their ventures, apparently ignoring suspicious deals.

But others saw a darker side of the Edmonds-Groves business model. Their security men spied and hacked – leaving some in fear of their lives.

Former cricketer Phil Edmonds. The Times

Global Witness drew on leaked emails and internal company files to map out Edmonds and Groves’ dealings, authenticating material with other sources and analysing meta-data on the messages.

The document cache includes a spreadsheet listing bribes to top Liberian officials, messages orchestrating stock market scams through offshore companies, and a forensic report detailing their security agent’s hacking operations.

“Mr Edmonds and Mr Groves deny any allegations of wrongdoing,” they said in a joint response to questions, telling Global Witness that they are “committed to ensuring that all their business is conducted in a responsible and ethical manner.”

They “are very proud of what they have achieved in business in Africa” and “feel very privileged to have been involved in so many ventures which were designed to develop business and industry across the continent,” according to the letter.

No one at Harbinger was aware of any improper payments or transactions, a spokesman for the fund said.

Edmonds and Groves are no strangers to controversy. In 2005, they set off a stock market bubble after their company White Nile negotiated an oil deal with rebels in war-torn Sudan.

“White Nile fever” raged on London’s AIM exchange, ending with a crash when it turned out the block they claimed already belonged to oil major Total.

Three years later, their AIM-listed mining firm Camec lent $100 million to Robert Mugabe’s regime on the eve of his victory in a crooked and violent election.

But markets have short memories and by 2009 Edmonds and Groves were back, selling Camec for just short of a billion dollars.

African Potash, one of the businesses they floated on AIM and where Groves still holds shares, boasts two former UK government ministers, Peter Hain and Mark Simmonds, among its directors.

Groves is currently an executive at three of the companies he and Edmonds have listed together on AIM: Sable Mining Africa, Atlas Development and Support, and Agriterra. Edmonds has gradually cut his ties with the duo’s stock market ventures.

He resigned from Agriterra on 22 April – the same day he wrote to Global Witness in response to allegations raised in this report. There was no connection, he said.

AIM’s 1,000-plus companies have a combined value of £71 billion, much of which comes from ordinary UK investors and pension funds.

The exchange’s reputation for lax oversight has seen it labelled as a “casino” by a senior US regulator and the exchange has been dogged by a series of scandals. Anonymously owned offshore companies are at the heart of the problem.

Global Witness’s findings show just how easily corporate secrecy can be exploited to undermine the system.

Hiding behind anonymous firms registered in tax havens, Edmonds and Groves carried off a multi-million-dollar heist on their own shareholders, funnelling profits into offshore trusts supposedly for the benefit of family members – a ruse they say kept the deals legal.

When the law got in their way in Liberia, they paid bribes to change it. In neighbouring Guinea, AIM-listed Sable Mining’s flagship project has put a World Heritage Site under threat.

Unbridled aggression

Phil Edmonds was “the most difficult player I have had to captain,” according to Mike Brearley, who led the England cricket team for much of the spin bowler’s career – but he was also one of the most brilliant.

A combination of brains, talent and unbridled aggression made him feared by batsmen the world over in the late 70s and 80s, and many saw him as Brearley’s natural successor.

It was a role Edmonds, a natural leader, craved. Were it not for his inability to get on with Brearley—and almost everyone else—he might have achieved it.

“Get off my fucking back, Brearley, or I’ll fucking fix you,” he told his captain in a spat about tactics, wrote Simon Barnes, whose 1986 authorised biography A Singular Man is a study of Edmonds’ curious blend of naivety and cynicism.

Naivety, Barnes says, in not foreseeing the consequences of the outburst, which irreparably damaged his career.

The cynicism was from Edmonds’ upbringing in Northern Rhodesia, modern-day Zambia, where his father actively supported leading black politicians in the years leading to independence.

“It is because of my father’s idealism that I became a cynic,” he told Barnes.

“The family became known as ‘the kaffirboeties’ – the black-lovers,” said Edmonds, now 65. “When we went to school, inevitably, there were plenty of fights.”

The white authorities forced his father’s soft-drinks business into liquidation.

When Kenneth Kaunda, an old family friend, became president on independence in 1964, Douglas Edmonds hoped his fortunes would turn. Instead he found the country’s first black leader giving all the best contracts to former enemies.

“My old man went to Kaunda once and asked him what was going on,” Edmonds recalled. “And the response was: ‘Well, we take you for granted. You’re one of us. But these others—we need to keep them happy.’”

"Expediency rules"

Edmonds took the lesson with him: first to Cambridge University, then to cricket and, soon after, to the City.

“Expediency is what rules,” he told Barnes. “Not nice liberal ideas.” It was a philosophy that would match him perfectly with Andrew Groves.

Much less is known of Groves than of his more famous business partner. But in a year-long investigation in which Global Witness spoke to people who have dealt with him all over Africa, two things stood out: he can be very charismatic and equally frightening.

Born in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1968, where his father served with the police either side of independence, Groves later settled in a seaside mansion in southern England, developing a taste for expensive cars and, as his partnership with Edmonds flourished, private jets.

One photo shows him grinning, arms folded, reclining on a new aircraft’s white leather seats.

Andrew Groves, Phil Edmonds "very charismatic and equally frightening" business partner. Global Witness

“Andrew’s very charming,” says Vivek Solanki, a doctor who became entangled with Groves through a deal to build African hospitals. “The guy can sell ice to Eskimos.” But the charm could rapidly evaporate.

Several people who spoke about him requested anonymity because they feared violence. Enemies received visits from the police and an old school friend, Wayne Stoltz, whose “security” work for Groves encompassed hacking and intimidation.

One former business partner was contacted by an ex-convict claiming he had been hired by Stoltz to “destroy” him.

“If you play straight with Andrew Groves then he plays straight with you,” Stoltz told Global Witness. “When people steal from him he gets upset.”

Groves’ hard-nosed tactics and Edmonds’ polished sales pitch were a lucrative combination. Global Witness’s report reveals the dirty tricks behind one of the stock market’s most feted double acts.

The Spin

Phil Edmonds playing cricket in 1985. Adrian Murrell / Getty

Starting in 2002, Edmonds and Groves listed nine companies on the Alternative Investment Market, London’s barely regulated junior stock exchange. They soon developed a dazzling array of tactics to bleed investors’ funds.

Phil Edmonds has had two careers: first as a sportsman, then as a mining baron—both built on spin.

“Edmonds is constantly trying to persuade a batsman to expect one kind of delivery and then confound him with another,” wrote Simon Barnes of the cricketer’s slow left-arm bowling in a 1986 authorised biography.

“It is a game like paper-scissors-stone, a matter of bluff and counter-bluff.”

Sporting guile was never quite enough for Edmonds and even in his playing days he could be overheard negotiating property deals on the Lord’s dressing room payphone.

Business deals gave him the same buzz as cricket, he told a BBC radio interviewer the same year.

Asked what one thing he would take to a desert island, he opted for a humidor packed with “the most magnificent handmade cigars in the world.”

To pay for his cigars – and much besides – Edmonds deployed his spinner’s arts in business. Quickly he learned that to make money in mining, you didn’t need profitable mining operations – just investors.

In partnership with Andrew Groves he listed nine companies on AIM, a junior market set up by the London Stock Exchange in 1995 to allow smaller companies to raise funds (see box below). Almost always, Edmonds-Groves companies made huge losses.

That scarcely mattered: with investors focused on short-term movements in the stock, they talked up share prices and siphoned off the cash.

"Management fees"

When it came to convincing big investors to buy in, Edmonds was key.

London’s Square Mile was full of cricket fans eager for a chat with the former England star and with his move to the City, the spin bowler drifted effortlessly from one bastion of the British establishment to another.

“Through cricket I have had so many opportunities to travel and make powerful contacts,” he told his biographer, explaining that he would usually wear a cricket blazer to meetings in the City. “It helps to break the ice.”

As Edmonds and Groves learned to navigate the City, they developed a repertoire of techniques for bleeding their stock market ventures.

Clever lawyers, offshore secrecy havens and the AIM market’s almost total lack of regulation helped them get away with it.

Some of the tactics were perfectly legal. They paid themselves substantial salaries – more than $10 million in wages from 2002 to 2015.

In 2014 they took home over $1.3 million between them, while the four of their companies trading on AIM at the time lost more than $60 million combined.

Next came the service charges. Between 2010 and 2015, Edmonds and Groves’ AIM-listed companies paid more than $5 million dollars in “management fees” to Ocelot Investment Group – a company “controlled by Andrew Groves”, according to stock exchange filings.

Like the salaries, the fees were legal. That didn’t make them a good deal for investors.

“You think this will fly with the shareholders?!” Vivek Solanki, their partner in African Medical Investments, wrote to the duo in April 2010 when he found out that management charges had all but wiped out the year’s profit. “This is going to look ridiculous.”

Then there was the rent. Edmonds and Groves have said they earn nothing from their headquarters building at 18 Park Street in London’s exclusive Mayfair district.

They get a rental income from the property – £345,000 in 2008 – but say they pass the full amount on to the building’s ultimate owner, Mirabella Properties Ltd, registered in the British Virgin Islands.

The limited documentation on Mirabella suggests its ultimate owners are Edmonds and Groves themselves: 18 Park Street was used as security on a loan from Butterfield Bank – the same bank used by at least one of Edmonds and Groves’ AIM-listed companies.

The managing agent for the property, Cyril Leonard, also looked after Edmonds’ family home in Notting Hill.

There was also Ely Place Nominees. Between 2002 and 2010, the tiny company owned by the duo’s lawyer quietly sold off shares in their listed companies worth more than £200 million.

It’s not clear where the money went – but there is evidence to link Ely Place with Edmonds and Groves.

Ely Place has had many clients and “on rare occasions the beneficiaries of sales may have been Mr Edmonds and/or Mr Groves," their lawyer Philip Enoch wrote to Global Witness.

Cash shells

As the pair launched company after company, a pattern emerged. Their businesses almost always began as "cash shells" – empty corporate vehicles floated on the AIM exchange that can later be filled with assets.

Cash shells can be a legitimate way for companies with meagre resources to raise money for acquisitions. Shareholders who fund them aren’t investing in a specific project so much as betting on the owners’ reputation and ability to generate a return.

For Edmonds and Groves, it was an opportunity to drain funds from investors.

Edmonds would wear a cricket blazer to business meetings. “It helps break the ice.”. Adrian Murrell / Staff

The duo listed seven shells on AIM between 2002 and 2013. Each time, they said the newly listed company was on the look-out for profitable businesses to buy.

That wasn’t the whole truth. Telling the markets they were looking for investments that made sense in purely economic terms, they were also lining up sweetheart deals with friends and cronies.

Central African Gold agreed it first acquisition less than two months after its 2004 listing, signing a deal to buy Golden Tau Mining, a small firm eyeing gold mines in Botswana.

“We listed on AIM in April and raised funds specifically for the purpose of securing acquisitions in this area,” Central African Gold director Roy Pitchford said in a stock exchange filing – omitting to tell the market that one of Golden Tau’s founding directors was Pitchford himself.

Deals for friends

African Medical did its first—and only—major deal with Vivek Solanki, Edmonds and Groves’ personal physician. And African Oilfield Logistics’ first investment, six weeks after listing, was in a firm run by Michael Pelham, a director of Edmonds and Groves’ South Sudan oil company, White Nile, and its successor, Agriterra.

BioEnergy Africa—later renamed Sable Mining—also struck its first deal close to home. It bought a Mozambican sugar cane company, ProCana, two weeks before listing in 2008. The sellers included Edmonds and Groves’ AIM-listed Camec and African Medical director Corne Holtzhausen was already a shareholder.

It isn’t illegal to do deals with friends. But at African Medical, it was just this type of cosy arrangement that was used to rip off shareholders: more than the rent, the management fees and the cronyism, it was secret insider deals that were bleeding away investors’ funds.

Lucrative swindle

Again and again, Edmonds and Groves used shareholders’ money to buy assets – a building in Mozambique, a hospital business in Zimbabwe or a jet aircraft – by acquiring shadowy shell companies in offshore havens like Mauritius and the British Virgin Islands.

Hiding behind corporate secrecy, they sold assets they already controlled to their own AIM-listed companies at inflated prices. They never declared their secret ownership – and ordinary investors had no way of knowing that the duo were on both sides of the deal.

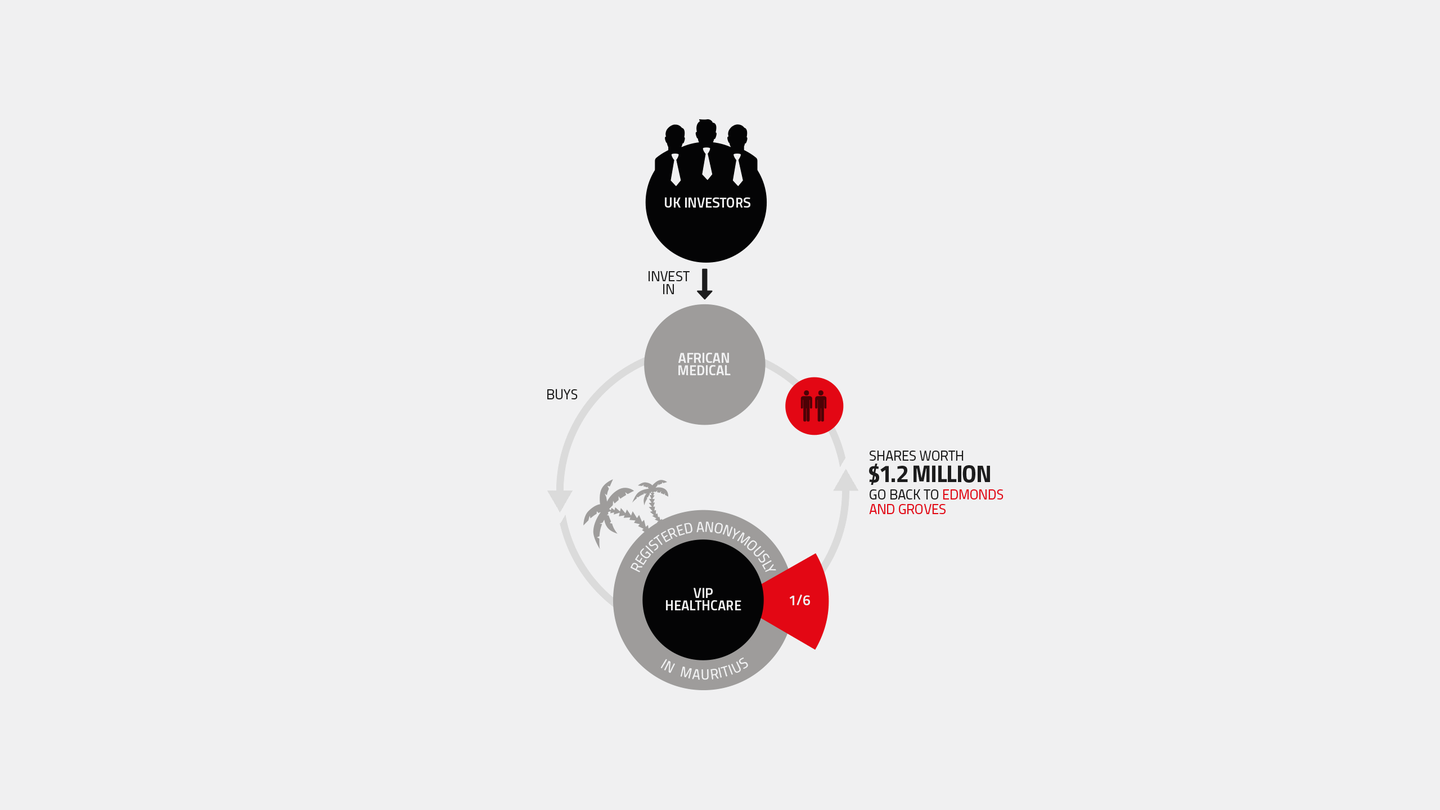

Global Witness

It was a lucrative swindle. The Mozambique property deal alone netted Edmonds and Groves’ family trusts more than a million dollars each in cash and shares. The hospitals transaction was designed to cream off shares worth $1.2 million – and it looks like Groves got at least $1.2 million more from the jet.

And those are just the ones we know about. Global Witness has found five other transactions that have the signs of insider transactions (see Chapter Five: The Heist). Secrecy havens and the market’s relaxed regulations made it easy for Edmonds and Groves to conceal their interests and fleece their listed companies with impunity.

At AIM-listed African Medical, Edmonds and Groves’ fees and schemes were crippling what should have been a profitable enterprise. The biggest investor, Harbinger Capital, had a seat on the company’s board during one of the scams. It put $38 million into African Medical. Why didn’t it raise the alarm?

Part of the explanation could be that Harbinger – a hedge fund run by billionaire Philip Falcone, who in 2013 paid $18 million to settle fraud charges in the US – was also pumping $58 million into another Edmonds-Groves company, Sable Mining.

With so much at stake, Harbinger may not have wanted to rock the boat. But why didn’t the authorities notice?

Edmonds and Groves’ Mayfair headquarters is owned by an company registered in the British Virgin Islands. Global Witness

"A front and an affront"

Maybe because no one was looking. AIM is so lightly policed that it’s sometimes known as the “unregulated stock market”. The UK Listing Authority, which monitors the main exchange, has no jurisdiction there.

AIM Regulation, the exchange’s oversight body, isn’t independent either: it's controlled by AIM’s owners, the privately run London Stock Exchange Group.

And in a glaring conflict of interest, the lawyers, stockbrokers and banks that earn fees from companies they bring to market – known as nominated advisers, or Nomads – are entrusted with the role of watchdogs.

The result has been scandal after scandal. AIM Regulation “is just a sham designed to lure investors into a false belief that the LSE’s junior market is policed,” wrote Nigel Somerville, a commentator at the finance website Share Prophets, in August 2015.

“It is a front, and an affront.”

Of course, not all of Edmonds and Groves’ corrupt deals were sophisticated market scams. In Liberia, they advanced their business with old-fashioned bribery.

AIM’s problems with anonymous companies

London’s Alternative Investment Market has seen so many disasters over its 20-year history that when a senior stock market official in the US called it a “casino”, the jibe stuck.

Secrecy over company ownership is often at the heart of AIM’s scandals. Yet regulators and law enforcement have taken little action.

Liberia: The bribes

When Sable Mining arrived in Liberia in early 2010, almost all of the country’s most valuable iron ore fields had already been parcelled out. Global Witness

Edmonds and Groves came to West Africa in 2010, hungry for iron ore. When the country’s public procurement law interfered with their plans, they set out to change it.

Leaked documents show how their London-listed Sable Mining spent hundreds of thousands of dollars bribing top officials. Behind the scheme was the chairman of Liberia’s ruling party, who doubled as Sable’s lawyer.

When Sable Mining arrived in Liberia in early 2010, almost all of the country’s most valuable iron ore fields had already been parcelled out. Just one prize asset remained. Andrew Groves was prepared to do anything to get it.

“Groves became obsessed with Wologizi Mountain,” an unmined range thought to contain a billion tonnes of ore, said one former colleague.

In his quest for mineral riches, Groves turned to Varney Sherman, Liberia’s best-connected lawyer.

Sherman works out of a two-storey pink villa in downtown Monrovia between the Royal Grand Hotel favoured by international corporations, and Vicky’s Fingers café, where locals eat chargrilled fish and plantain on the street. During 2010, Sable executives shared his offices as they drew up their battle plan for Wologizi.

One obstacle stood in their way. Wologizi had been earmarked for public tender – and in an open auction a smaller company like Sable might easily find itself outbid. But Sherman had a plan: if he could engineer a change in the law, they could circumvent the process.

It would mean bribing a lot of people. He drew up a list, according to a source with knowledge of the company, and Sable’s London attorneys started transferring the cash.

At Sherman & Sherman’s Monrovia office, Sable hatched a plan to win mines with bribes. Global Witness

By August 2010 Sable had paid out more than $200,000 earmarked for some of the most powerful people in Liberia: the speakers of both houses of parliament, senators, ministerial aides and at least one minister.

The payments are listed in a cache of documents leaked to Global Witness, including a spreadsheet from Sherman’s law firm listing many of the biggest sums.

Alongside the bribes, thousands more went on entertaining the president’s son, the documents show.

“If your allegations are correct, none of these actions were carried out with the knowledge of the board,” Edmonds and Groves told Global Witness in a letter—though the documents show that the bribe spreadsheet was emailed directly to board member and chief executive Andrew Groves.

Sable said it conducts its business “in a responsible and ethical manner”. It said it had conducted a review into the payments in 2011. No evidence implicating the board was found, it said, and financial controls were tightened as a result. The payments were made by Delta Mining, in which Sable had only a minority interest, the company said.

But by the time the bribe payments started Sable had already signed agreements to take control of the company, and the payments came from Sable’s account not Delta’s, the spreadsheet shows.

Sherman said by telephone that he had made payments on behalf of Sable but couldn’t comment because they were confidential.

For the Liberian lawyer, it was more than just a job for a client: he had ambitions of his own. Sable paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to fund the convention that saw him elected chairman of the ruling party. Another donation helped him push out a party rival.

In the end, Groves’ bribe-fuelled obsession would come to nothing. But Sherman would be sitting pretty.

"A national cancer"

“Corruption is a national cancer that creates hostility, distrust, and anger,” President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf said when she became Liberian president in 2005, pledging a war on graft to resurrect a nation destroyed by 14 years of civil war.

No one seems to have told Edmonds and Groves. Their London-listed company Sable got into Liberia in early 2010 with its deal to buy into South Africa’s Delta Mining . The purchase was backed by more than £60 million in cash from US hedge funds and investment banks, over half of it from Philip Falcone’s Harbinger Capital.

Delta had a controversial history in Liberia. In 2008, it had missed out on one of Liberia’s biggest iron ore concessions, the Western Cluster, after its winning bid was disqualified amid bribery allegations.

But in a closed-door meeting at the presidential mansion, Delta had struck a deal with the government. Officially cleared of corruption, Delta and its new shareholder Sable were now convinced that they could get Wologizi instead.

Big miners like Australia’s BHP Billiton had already done early work at Wologizi, widely considered the country’s richest unattributed iron ore concession, though they had never got beyond the exploration stage.

Now, with commodity prices at record levels, it was bound to be snapped up. Sable shouldn’t risk bidding in an open tender, Sherman told them.

Fortunately for Edmonds and Groves, a new Public Procurement and Concessions Act was on its way through parliament. By bribing the right people Sable could get a loophole inserted allowing it to win the mountain without a tender, said Sherman, according to a person familiar with the scheme.

The spreadsheet, listing outflows from Sable’s client account with his law firm Sherman & Sherman, give details of the pay-offs.

"Payment (facilitation) revised PPCC Act£ is the label for one transfer of $75,000, a transaction marked in other leaked documents as "Consulting fees – A Tyler".

Alex Tyler, speaker of Liberia’s House of Representatives at the time, helped to get the Sable-friendly legislation through parliament.

Other outlays on Sherman’s bribe sheet included:

- $50,000 to Morris Saytumah, a presidential aide and cabinet minister who was “President Sirleaf’s representative on concession negotiations”, according to a leaked US diplomatic cable

- $50,000 to Richard Tolbert, a former Wall Street banker who headed the National Investment Commission—key to granting licences and setting terms for foreign investors

- $10,000 to Willie Belleh, chairman of the Public Procurement and Concessions Commission—responsible for all investment agreements with the Liberian Government.

Vicky’s Fingers café, where locals eat chargrilled fish and plantain on the street. Global Witness

The bribe payments, corroborated by internal financial records also seen by Global Witness, were transferred to Sherman by Sable’s London law firm Salans. Sable’s internal records list the outlays as “consultancy fees”, as with the $75,000 payment to Tyler.

Another $20,000 went to the Invincible Eleven, a football club where Tolbert was president. And a separate document shows half a million dollars in payments to "Bigboy 01" and "Bigboy 02" – whose identity Global Witness was unable to establish.

Contacted by Global Witness, Tolbert and Belleh denied taking bribes from Sable. Tolbert acknowledged accepting payments to the football team. Saytumah and Tyler did not respond to letters hand-delivered to their offices.

Sable’s lawyer, Philip Enoch, said Salans was acting on the company’s instructions when it transferred the funds to Sherman's law firm and had no reason to question the payments.

Sable’s lawyer, Enoch, said Salans was acting on the company’s instructions when it transferred the funds to Sherman's law firm and had no reason to question the payments.

By August 2010, when Sherman emailed the spreadsheet to Groves, Sable’s Wologizi gambit was at a critical juncture: the Public Procurement Act was close to being made law and it looked as if months of painstakingly targeted bribery were about to pay off.

“We finally got the Revised PPCC Act completed,” Belleh wrote to Sherman on 6 August 2010. “The Minister of Justice and I met with the President last night and reviewed areas of concern to her. She approved. The document has been forwarded to the National Legislature. It is expected to be fast-tracked.”

“This is good news,” wrote Sherman, forwarding Belleh’s email to Sable.

"You will be milked like a cow"

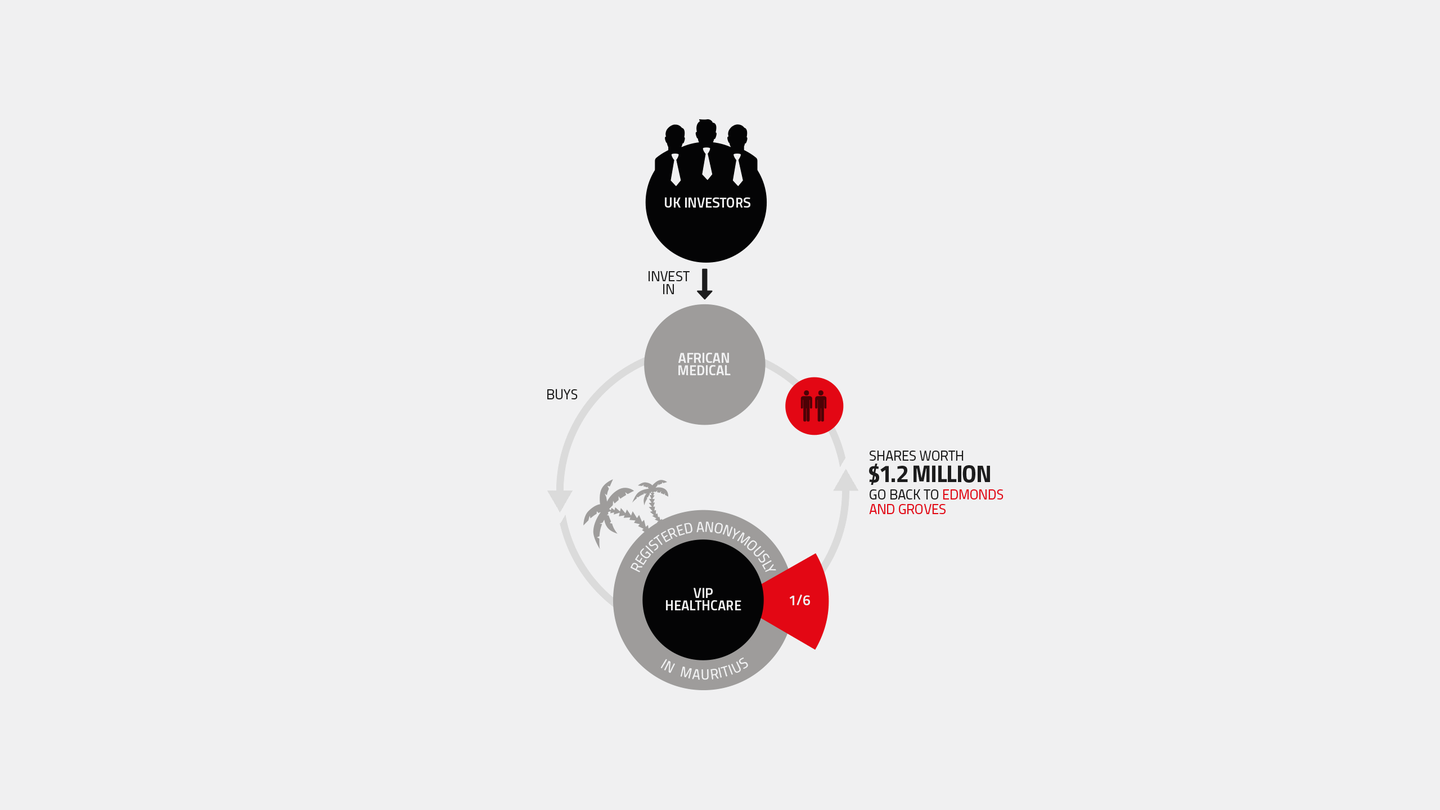

There were hiccups, though. On 7 August, the head of Sable’s Liberian operation, Heine van Niekerk, emailed Sherman with news of a worrying phone call. It seemed Tyler was unhappy with his $75,000 payment: the Speaker had rung to say that getting the Act through the senate would cost “about US$250,000,” van Niekerk told the lawyer.

Sherman was alarmed that Sable might over-bribe.

“Heine, don’t do that please!” he replied that evening. “You will be milked like a cow.”

Liberia’s new Procurement Act passed on 16 September 2010, complete with the new provisions Sable wanted. Article 75 allowed the mining minister to declare a mining concession as a “non-bidding area” – that is, one that could be handed out without a tender.

Meanwhile, Sable’s money was doing more than just changing the law. Also on Sherman’s spreadsheet are payments with little obvious connection to Sable and Delta – and much more to do with the bagman’s personal aspirations within the ruling Unity Party.

A $200,000 payout from Sable’s funds labelled "political contribution – UP convention" is dated 22 April 2010 – less than three weeks before a Unity Party conference where Sherman was elected chairman unopposed after his opponents “were persuaded to back off,” according to a local newspaper.

Party games

Sable’s cash was also there to fix things when they went wrong. At the same convention, Unity Party members elected Henry Fahnbulleh as Secretary General – not the result Sherman wanted. He publicly demanded Fahnbulleh’s resignation.

“I have no intention of stepping down,” Fahnbulleh told the press. “The principle is wrong and I am willing to die.”

On 24 June 2010, a payment of $25,000 left Sable’s account with Sherman & Sherman. It was labelled "Political contribution – UP Secretary General resignation". Fahnbulleh quit the next day.

In an August 2015 interview in Monrovia, Fahnbulleh told Global Witness how he suddenly came under huge pressure from traditional elders to step down. “Don’t fight your big brother,” they told him.

Elsewhere, Sable was pursuing more friends in high places. In 2011, it spent thousands of dollars entertaining Fombah Sirleaf, the president’s stepson and Liberia’s chief of intelligence.

Sable executive Heine van Niekerk took him on an all-expenses-paid hunting trip to South Africa and kitted him out with gear. They shot four animals, including a gnu, and Sable paid to have them stuffed, tax invoices show.

Sable later bought Sirleaf a phone and on 12 May 2011 spent $1,070.87 on him at Twin Bore Agencies, a Johannesburg gun shop. There is no evidence that Sirleaf provided Sable with any favours, though he was clearly a useful person to know.

Van Niekerk declined to comment for this report.

False promises

Liberia’s procurement act was changed as planned. But did Edmonds and Groves get what they wanted? The biggest prize, Wologizi, remained tantalizingly out of reach.

“It seems certain people high up in Liberia had promised it to various parties from different countries and had not cross-checked,” says one person familiar with the scramble for Liberian iron ore concessions at the time.

Responding to Global Witness, the Liberian government said it will “spare no efforts in getting to the bottom of the issue and bring to justice anyone found culpable.”

Instead of Wologizi, Sable had to make do with three smaller licences—Timbo, Bopolu and Kpo—and on the London market where Sable’s shares were traded, Groves did his best to talk up the assets. But all three turned out to be practically worthless.

That didn’t mean Sable’s efforts were wasted. By 2012 the firm was touting a new iron asset on London’s Alternative Investment Market—Mount Nimba, just across the Liberian border in Guinea.

Nimba helped bring fresh investment, including from Credit Suisse and JP Morgan Chase & Co in the US.

But Sable and its backers knew that the project was unviable without permission to export ore through Liberia – something that some of Sable’s larger competitors had tried, and failed, to procure.

In January 2015, the Liberian government signed the export permit. In London, Sable shares went through the roof.

Sable Mining: bribes and questionable payments in Liberia

Guinea: The prize

After Liberia, Edmonds and Groves set their sights on a new prize: Mount Nimba in Guinea. Global Witness

After Liberia, Edmonds and Groves set their sights on a new prize: Mount Nimba in Guinea.

To win it, their company Sable Mining – still listed on AIM – got close to the future president, backing the campaign that brought him to power, courting his son and paying millions to one of his close friends to advance their business with bribery.

August 2010. Guinea is in the grip of election fever as the impoverished West African nation prepares to end five decades of dictatorship with its first free vote.

Presidential candidate Alpha Condé is flying in with Sable Mining chief Andrew Groves – and Sable’s man in Conakry is worried the price of bribes is about to skyrocket.

“Once we get there on a plane with presi, the future head of the country, and two ‘big-shots’ from a big western company, trust me, prices will inflate like crazy,” Sable’s Guinean agent, Aboubacar Sampil, wrote in a 28 August email to a Sable executive.

“Folks in the admin will try to get a lot, lot more for each step, leading to a minimum of about $500,000 not including the minister’s share.”

The email is among a cache of documents leaked to Global Witness by sources who requested anonymity.

Sable, listed by Edmonds and Groves on AIM in 2008, had spent the previous months lining up its first iron ore rights in Liberia. Now it was backing Condé’s campaign in neighbouring Guinea.

To get close to Condé, Sable was courting his son, Alpha Mohamed Condé – with the implication that when his father became president, Sable’s interests in Guinea would be taken care of.

“We look forward to bringing this political collaboration to life,” Alpha Mohamed wrote to Sable on 4 August 2010. “It will make my dad all the more comfortable to support our business partnerships and trust us as a team to be solution providers for many of the challenges he will face.”

Mount Nimba, a World Heritage Site where mining threatens rare chimpanzees and toads. Global Witness

As Sable took care of campaign logistics – booking flights for the Condés, arranging meetings with a Liberian minister and the heads of South African intelligence, and offering the loan of a helicopter – its agent Sampil, an old confidante of Condé and a member of his entourage, was on the ground in Guinea scouting for permits.

To get them, he wanted money for bribes. Four times that August Sampil asked Sable for money via Alpha Mohamed’s Paris bank account, leaked emails seen by Global Witness show.

“Now it is very important to make money transfer to the Alpha bank account. That can help to finalise faster with the technicians of the ministry,” Sampil wrote on one occasion.

“They started giving me some information that I have to pay for. You know how things work.”

Prime territory

Alpha Mohamed had sent Sable his bank details earlier in the month – but wiring cash to the son of a high-profile politician was proving tricky.

“We are having a few issues with our risk/compliance people in terms of getting this payment made,” wrote Sable’s London lawyer on 17 August.

Groves suggested routing the payment through a Sable account in South Africa.

“Alpha Condé paid,” Groves wrote a few hours later to say he had sent the son his money.

But 10 days later Sampil, who had asked for 15,000 euros, was still complaining that the transfer hadn't come through.

Alpha Mohamed told Global Witness that he had never “attempted to use improper influence to assist Sable” – though the emails show that he was aware of plans to send bribe money through his account.

“Any payments to Alpha Mohamed Condé from Sable Mining would have been for consultancy work or reimbursement for travel,” a spokesman for the Guinean government said.

Alpha Mohamed “would be able to show that his bank never had more than 10,000 euros in his account”.

Sampil declined to comment for this report.

Edmonds and Groves told Global Witness that if any bribery occurred in Guinea, it was without their knowledge.

Jim Cochrane, Sable chairman since 2014, said the company obeys the law wherever it operates and that questions from Global Witness had “prompted a further internal review of all these matters, many of which were subject to review a number of years ago”.

Global Witness’s investigation did not reveal any evidence of wrongdoing by Alpha Condé Sr.

Condé won the election. And whatever Sampil was doing for Sable, by January 2012 his efforts were paying off.

One of the key permits Sampil had applied for during the election campaign – when he was soliciting bribe money from Sable – came through: iron ore exploration rights in Mount Nimba on the Liberian border, prime mining territory close to concessions held by multinationals BHP Billiton and Arcelor-Mittal.

Sampil was handsomely rewarded. Sable appointed him a non-executive director with an annual salary of $120,000 and in 2014 paid him $6 million in “consultancy fees”. His importance to Sable “cannot be underestimated”, the company’s lawyer said in a 2012 court filing.

Sampil “does not hold any position with the government of the Republic of Guinea and does not represent the administration in any capacity”, the company told the Times.

Payments to him were “fully justifiable and have been disclosed fully,” Cochrane wrote to Global Witness.

There was just one problem with the Nimba permit: it was illegal.

Special treatment

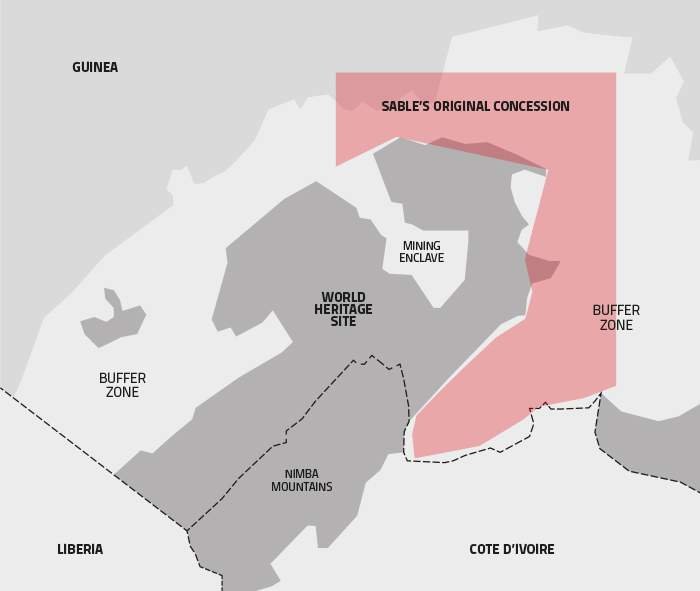

Maps of the exploration area granted to Sable show that it overlapped with the Mount Nimba Strict Nature Reserve, a World Heritage Site on Unesco’s danger list, home to the rare Western chimpanzee, already extinct in nearby Gambia, and the critically endangered Western Nimba viviparous toad, one of the only toad species that spawns live young.

While Sable’s permit was later adjusted to skirt the reserve just outside the boundary, in some places it remained less than 90 metres from the park. It also covered swathes of the buffer zone surrounding the reserve, which is also internationally recognised.

Sable’s original site overlapped the Nimba reserve. Later it was adjusted – but was still illegal, Guinea’s environment minister said. Global Witness

Letting Sable operate there “contravenes commitments made by our government to the international community”, warned environment minister Samady Touré in a letter to the mining minister on 9 August 2012, four days after the permit was revised.

The company’s activities “are incompatible with the current status of the Strict Nature Reserve” under Guinean law, wrote Touré, who requested the cancellation of the permits.

“This contract involves a licence on the buffer zone of the Nimba site and not the protected area. It was believed that this would have lower negative impact,” a spokesman for the Guinean government told Global Witness in an email.

“The basic premise of preferential treatment for Sable from the Condé government is simply incorrect.”

"A quick and dirty job"

Touré’s protests went unheeded and three months later he was dismissed. Unesco officials who visited Nimba in 2013 feared for the future of the reserve.

Sable’s planned mine could squeeze a band of endangered chimpanzees into a narrow corridor between mining concessions, said the Unesco team’s report, and forest landscapes already threatened by hunting, logging and farming would be isolated and fragmented.

But with no power to stop Sable, all Unesco could do was urge the company to carry out environmental impact assessments to the “highest international standards”. The report Sable produced in February 2015 didn’t come close, according to a senior Unesco official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

It was a “quick and dirty job,” the official told Global Witness. Sable’s consultants spent so little time in the field that they even mistook passing migrant birds for native wildlife.

“The bird inventory has as the two most common species two migrant species from Europe because they just did the inventory on the days they came through,” the official said. “It is very clear that they didn’t do proper baseline studies.”

Parts of the report, seen by Global Witness, look suspiciously like a hasty cut-and-paste job. Sable’s concession is a “nesting site for marine turtles,” it says. Nimba is 270 kilometres from the sea.

Secret recordings

On the ground in Nimba, Sable plied local officials with gifts to keep them on-side. In secret recordings of speeches from a village ceremony in July 2013, Guinean officials can be heard thanking Sable for its gifts: Sable renovated the local prefect’s house; local environmental and mining officials received 11 motorcycles and a pick-up truck.

With the officials taken care of, Sable had just one hurdle left to clear: getting its ore out of Guinea.

It was a nut that far bigger mining companies had failed to crack. Guinea’s big iron deposits are in the country’s south and east, from where the easiest export route is a short haul across Liberia to the coast by rail.

But Guinea’s government was desperate for infrastructure, insisting that companies fund a much longer and costlier railway to the Guinean capital that would carry passengers as well as ore.

In August 2013, Sable succeeded where its competitors had failed when a Guinean ministerial decree granted the company the right to export through Liberia. With the Guineans onside, the Liberians followed, signing an export deal with Sable on 23 January 2013.

In London, the news sent Sable stock rocketing more than 300 per cent. But Edmonds and Groves may not have been telling investors the whole story. The Liberian railway was in the hands of international steel giant Arcelor-Mittal and the arrangement to use it was far from a done deal.

“There’s nothing agreed yet on the railway,” a person with close knowledge of talks between Arcelor and Sable told Global Witness, speaking anonymously due to the confidentiality of the discussions.

Far from having secured an export route, Sable was more likely to end up fighting a “lengthy court battle”, the person said.

The railway deal is “not yet consummated”, the Liberian government told Global Witness.

"Just do what I do"

With a rail deal nowhere near as close as he was publicly claiming, Groves offered Arcelor an alternative: buying Sable’s ore “at the mine gate”, leaving the larger company to take care of transportation.

But Arcelor officials suspected Groves of exaggerating the quality of Sable’s deposit, cherry-picking the best samples to make the overall quality seem higher, insiders say.

Even as iron ore prices slumped in 2014, Sable continued to tell the markets that Nimba was a workable prospect. But it’s unsure the company will ever get any iron out of Guinea.

Since Sable arrived in West Africa, Guinea has been hit by a deadly Ebola epidemic that left 2,536 dead and few companies with appetite for the foreign investment needed for recovery.

But Andrew Groves has some advice for those who do feel equal to the challenge, say two people who attended a meeting with him in 2014.

“Just get them all round the table – army, police, government, environmental, doesn’t matter who it is – we get them all round the table and we just give them money to make things happen and it all just goes away,” Groves said, according to one of them (the other gave a similar account).

“You should just do what I do. Because everything goes smoothly when you do it like I do.”

Mozambique: The heist

When African Medical bought the company that owned the site in Maputo, Mozambique, it was really buying from Edmonds and Groves themselves, documents show. Getty

Edmonds and Groves don’t always have to go far to find a deal – they can simply do business with themselves.

Using secretive offshore companies as cover, they siphoned off millions of dollars by selling assets to their own listed companies at bumped-up prices. Top City law firm Salans helped structure the transactions.

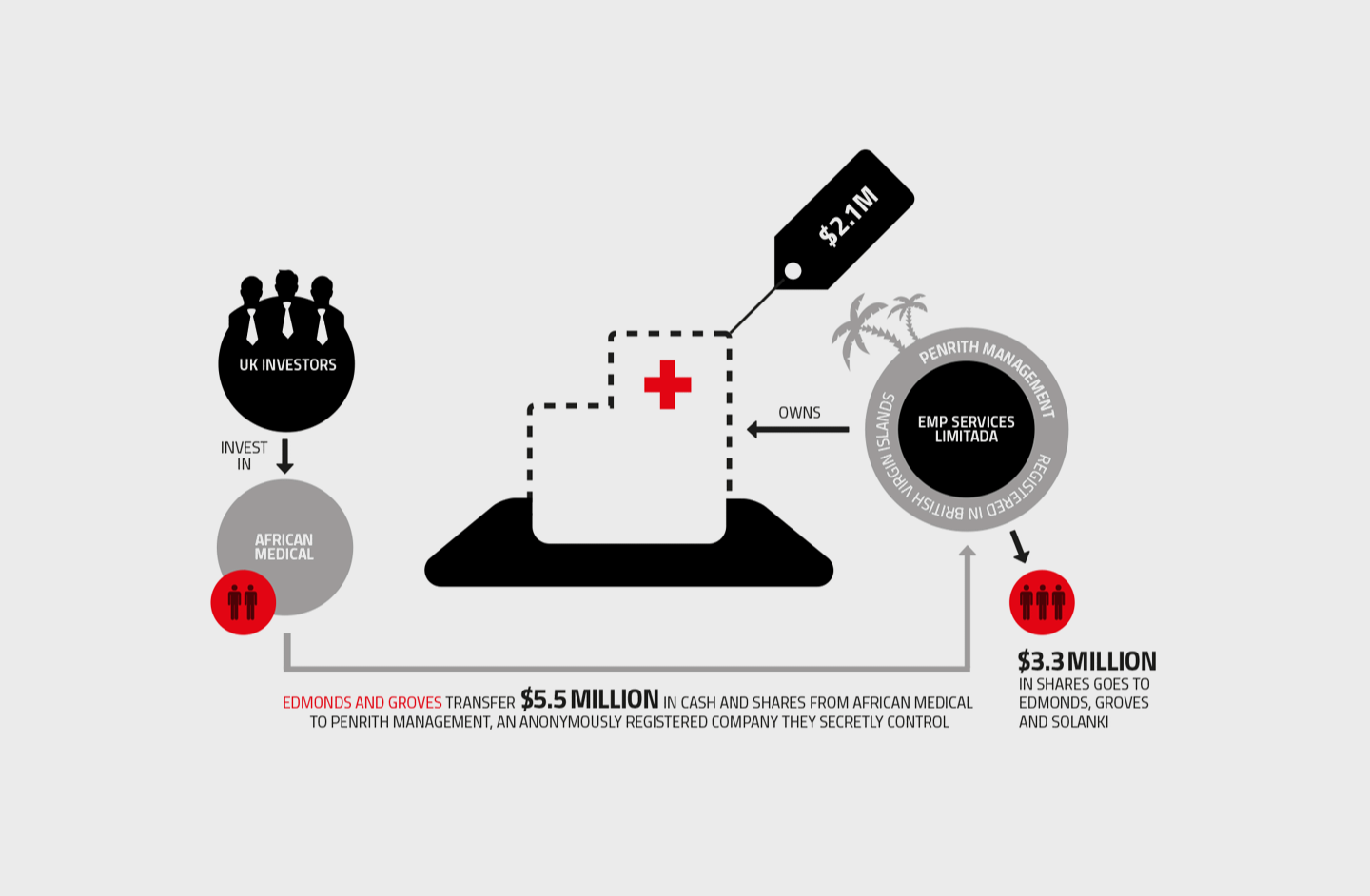

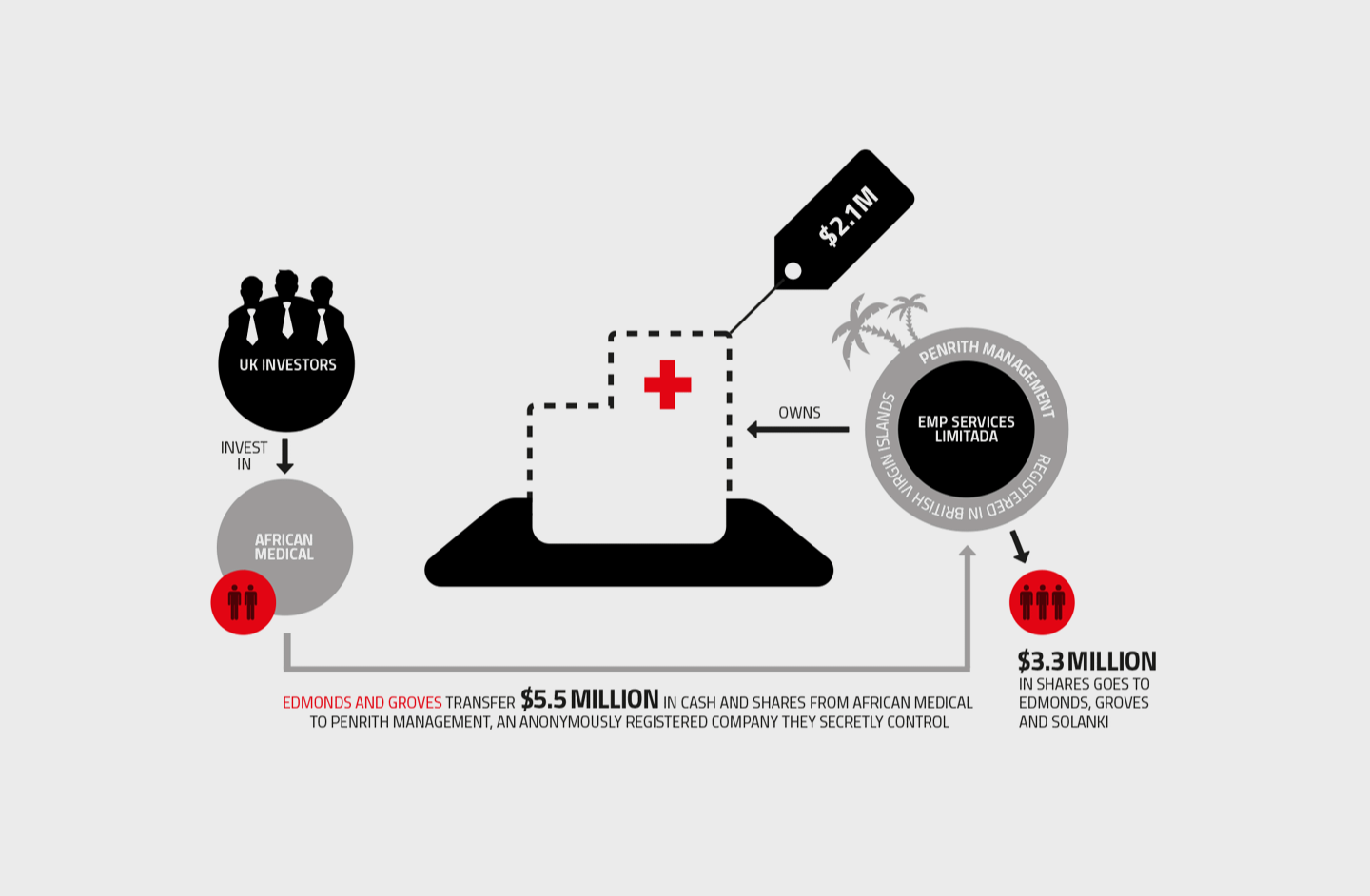

It was mid-2009 when African Medical Investments announced the acquisition of a tiny Mozambican firm “whose sole asset is a substantial sea view property located in the exclusive Polana district of Maputo.” It was the start of a three million dollar scam.

African Medical, the latest in a string of Edmonds-Groves stock market ventures, had already raised £5 million by listing on London’s AIM exchange. People who bought the shares may have thought the company was using their money to develop private clinics in Africa.

Leaked emails suggest that profits were flowing straight into the pockets of Edmonds and Groves.

Edmonds and Groves had known Vivek Solanki, a Zimbabwean trauma surgeon with a talent for building private clinics, for years as patients. They made him a proposition: with his experience and their network, they said, they could build hospitals all over Africa.

By September 2009, African Medical had branches in South Africa, Zimbabwe and Tanzania, and was ready to expand again, this time in Mozambique.

When African Medical bought the company that owned the site in Maputo, it was really buying from Edmonds and Groves themselves, the documents show. Such transactions should, by law, be publicly disclosed.

But that would have meant revealing the heist on shareholders. Instead they found a loophole that let them use offshore trusts to get around the law.

“The transaction was an elaborate and deceitful fraud,” wrote Peter Botha, African Medical’s current chief executive, in a May 2013 sworn statement. Edmonds and Groves told Global Witness that it was legal and “in the best interests of shareholders.”

Groves and Solanki holidayed together in Zanzibar – before their relationship turned sour. Global Witness

The Maputo deal wasn’t a one-off. Evidence uncovered by Global Witness suggests Edmonds and Groves repeated the ploy time and again.

London’s notoriously under-regulated AIM exchange, secrecy havens like the British Virgin Islands and the services of a top international lawyer helped them do it.

This is how it worked.

"Insider job"

African Medical didn’t buy the land for its new Trauma Centre and Well Woman Clinic in Maputo directly. Instead it bought a local company that owned it, EMP Services Limitada. The seller of EMP Services was Penrith Management Trading, registered anonymously in the British Virgin Islands.

Leaked documents show how all three companies in the chain were connected to Edmonds and Groves.

First, their associates set up EMP as a local front company to buy the site. Shortly after, the associates transferred their shares to BVI company Penrith – secretly run by Edmonds, Groves and Solanki. Using the British Virgin Islands’ anonymity rules to mask their identity, Penrith then sold EMP on to African Medical at a massively overblown price.

Land plot

EMP originally bought the property in October 2008 for just $2.2 million, the documents show. By the time Penrith sold EMP to African Medical less than a year later, that price had been marked up to $5.5 million, paid to Penrith in cash and shares.

African Medical’s investors, whose money funded the deal, had no way of knowing that Penrith already belonged to Edmonds, Groves and Solanki – and that they were the victims of a three-million-dollar rip-off.

A leaked November 2008 email from African Medical’s manager in Mozambique reveals who secretly controlled Penrith: when he needed Penrith to make a payment, he addressed his request to Solanki, Edmonds and Groves.

“I’ve had a discussion with Andrew and Phil,” the manager wrote. “We have to make the first payment immediately.”

“Penrith is a company owned by Groves, Edmonds and myself,” Solanki wrote in June 2012 in another email seen by Global Witness. “EMP is also owned by Groves and Edmonds. This was a complete insider job.”

Even EMP’s name was a giveaway, Solanki told Global Witness in an interview: it’s a reversal of the initials of Philip Maurice Enoch –Edmonds and Groves’ longstanding lawyer, who incorporated Penrith.

“I will sort out the BVI company,” Enoch wrote to Solanki on 19 November 2008.

Global Witness

When The Times raised concerns about the Maputo deal in December 2014, a spokesman for Edmonds and Groves “declined to identify the ultimate owners of Penrith”. Any link between EMP Services and African Medical’s managers could “prove discomforting for retail investors,” the UK newspaper said.

Pressed by Global Witness, Edmonds and Groves admitted ties to Penrith. But they and their lawyer said the deal wasn’t against the rules because Penrith was owned by family trusts for the benefit of their relatives.

Under market rules, “related parties” who do deals with each other need to declare them. But the definition of a related party varies.

The International Accounting Standards that Edmonds and Groves’ companies claim to follow define close members of a director’s family as any relative who “may be expected to influence, or be influenced by, that person.”

AIM’s version, meanwhile, is so narrow that it only stretches to a director’s children and spouse. Uncles, aunts, cousins and even siblings don’t count.

It’s a useful ambiguity that Edmonds and Groves say kept their deals legal. They declined to tell Global Witness which relatives benefited from the trusts but said they do not fall within the definition of related parties.

Whatever the exact family relationship, duping shareholders to skim off profits would still constitute “powerful grounds for suspicion that a fraud has been committed”, a top international law firm told Global Witness.

"Family trusts"

Edmonds and Groves offered an explanation for the land deal.

“Non-related family trust entities were already in the process of acquiring a property for themselves” when African Medical was independently seeking a site for its Maputo hospital.

“They agreed to hold the property for African Medical until it was in a position to proceed to occupy and rent the property for hospital purposes.”

According to this explanation, it was just a fortunate coincidence that the Edmonds, Groves and Solanki families combined to buy a property exactly where and when African Medical needed one.

When African Medical bought it just nine months later, the site had more than doubled in value and the company paid a fair price, Edmonds and Groves said.

But Global Witness spoke to three Maputo real estate brokers who all said there was no way prices could have leapt 160% in just nine months. The highest estimate for the change in the period was 20%; one broker said prices barely changed.

And from the leaked e-mails, it’s clear that the family trusts were no more than camouflage: the deal was a three-way split between Solanki, Edmonds and Groves from the outset.

“Could you please confirm the name of the company that sold the Maputo land and share allocation thereof (I have one third of this)?” Solanki wrote to Enoch, Edmonds and Groves’ lawyer, on 19 May 2010.

Solanki told Global Witness that he only got back what he put into the deal in cash, and that he never received the shares that should have been paid out to him.

To the regulators, Penrith’s true ownership didn’t matter. No one was checking – and even if they had, the offshore smokescreen made it almost impossible to find out. The losers were African Medical’s investors, conned into buying an asset for more than twice what it was worth.

Plane secrecy

In 2010 Philip Enoch helped African Medical with another purchase – a jet aircraft for use as an ambulance.

It was the Mozambique property scheme all over again, say Solanki and Botha, the former and current African Medical chief executives. Andrew Groves fleeced African Medical’s shareholders by selling the London-listed company an asset at an inflated price and siphoning off the difference, they say.

“This was an Andrew deal,” Solanki, who was dismissed from African Medical after a dispute with Edmonds and Groves, told Global Witness. “In those days he would confide in me, tell me, because he liked to show off how he managed to get deals.”

African Medical paid $3.1 million for the plane, a Dassault Falcon 20, in 2010 – even though a leaked email from the company’s accountant suggests the real value was far less.

“I have included a spreadsheet on the Falcon 20,” the accountant, John Raath, wrote to Groves and Solanki on 27 April 2009. The calculations are “based on a $1.875 million purchase price.”

Leaked documents suggest Groves secretly sold his own plane to African Medical—at a $1.2 million mark-up. Gary Shephard

As with the Maputo property deal, it looks like the over-valued asset being sold to African Medical already belonged to Andrew Groves.

Research by Global Witness shows how before the sale the aircraft passed through a string of opaque companies all connected with Groves.

In 2006 it was owned successively by two companies, Roston Aviation in Delaware and Gough Aviation in South Africa. The sole director of both was Groves’ pilot, Roston Gough Smith. Gough Aviation belonged to Camec, listed on AIM by Edmonds and Groves.

When they sold Camec in 2009, the jet was hived off to a South African-registered firm, Caramix, itself owned by a secretive British Virgin Islands firm. It was Caramix—where Roston Smith was again a director – that sold the Falcon to African Medical.

"No, no, no"

Solanki, who is still fighting his former employers in court, says the plane belonged to Groves; another African Medical insider, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said the same.

So did Peter Botha, in a signed affidavit handed to the UK’s Serious Fraud Office as part of a dossier of fraud allegations. African Medical left AIM in early 2014 and is now being wound down.

Groves didn’t answer questions from Global Witness about the jet. Enoch said he had assisted in the purchase of the aircraft and had “no reason to believe that this constituted a ‘related party transaction.’”

The deal was later cleared by law firm Baker & McKenzie, he added. An SFO spokeswoman said it was the organisation’s policy neither to confirm nor deny if an investigation was in progress.

Groves scooped at least $1.2 million on the deal – and $200,000 more when he even got a tax rebate, the documents suggest. To people on the inside the scam should have been obvious.

But it seems not everyone cared. US hedge fund Harbinger Capital, the biggest shareholder at the time had a seat on African Medical’s board.

By the time the directors met to vote on the deal, the price had been jacked up from $1.9 million to $3.1 million, “supported by a valuation which Andrew has obtained,” according to a 25 February 2010 email from Enoch to Solanki.

“No, no, no, that’s not agreed,” Solanki recalls saying at the board meeting.

But everyone else backed the deal – including the man from Harbinger.

“Harbinger is not aware of any fraud in connection with the jet purchase,” a spokesman said.

Offshore secrets

It wasn’t just the Mozambique property and the jet. There’s evidence that Edmonds and Groves pulled the same scam over and over.

Global Witness has identified five more deals in which their listed companies bought assets from Caribbean shell companies – all with the same address as Penrith, the front for the Maputo fraud. It’s a remarkable coincidence.

The assets are seemingly unrelated – a tin venture in Namibia, a platinum one in South Africa, farmland in Sierra Leone – and on the face of it, there was nothing to connect them with Edmonds and Groves; yet every one of the sellers was registered at the same address in the British Virgin Islands.

That’s because they were all incorporated by Nerine Trust, a company services provider that has a long relationship with Edmonds and Groves.

Nerine created three companies – Ashendon, Eglinton Management, and Eriswell – that stock market filings show are controlled by trusts for the benefit of Edmonds and Groves’ relatives.

There were some 120 service providers in the BVI – yet wherever the duo did business it was Nerine that incorporated the anonymously owned company on the other side of the deal.

It’s a clue that Edmonds and Groves may have taken the scam well beyond the deals for the Maputo property and the jet, routinely selling firms they secretly controlled to their listed companies in London and skimming off investors’ cash.

And it was Enoch, a partner at the international law firm Salans, who helped arrange the deals. He and a secretive company he owned, Ely Place Nominees, were central to another Edmonds and Groves insider scam—one engineered to earn them a $1.2 million kickback.

More dodgy deals?

In 2010 Edmonds and Groves sold property they secretly owned to one of their listed companies, deceiving shareholders and pocketing millions. To hide their ownership, they used Nerine Trust, a corporate agency in the British Virgin Islands.

Edmonds and Groves’ companies on the stock market have struck at least five other deals with secretly owned firms registered in the British Virgin Islands by Nerine. Were Edmonds and Groves among the secret owners, and have they fleeced investors through the same trick again and again?

The six Nerine deals Global Witness has identified:

- 20 June 2002: Camec pays Namibian Resources Company $2.5 million for 75% of Namibia’s Goantagab Tin and Tantalum Company (Proprietary) Ltd. Namibian Resources Company was registered by Nerine.

- 26 November 2002: Southern African Resources buys 50% of Birkwood’s stake in South African platinum company Biz Afrika 1673 for £80,000 plus 30 million shares. Birkwood was registered in the British Virgin Islands by Nerine.

- 27 March 2007: Camec buys a maize-milling operation from Goodworth Services, registered by Nerine.

- 27 March 2007: Camec buys 44.5% of South African platinum company Pfula Investments for £7.5 million. It buys Pfula from Transafrica Investments, registered by Nerine.

- 30 September 2009: African Medical Investments agrees to pay $5.5 million to Penrith Management Trading for EMP Services. Penrith was registered by Nerine—and secretly owned by Edmonds, Groves and the CEO of African Medical.]

- 1 December 2011: Agriterra buys Shawford Investments, the parent of Red Bunch Ventures (SL), owner of farmland in Sierra Leone. Shawford was registered by Nerine.

London: The enabler

It was on London’s junior stock exchange that Edmonds and Groves turned their assets to cash. Shutterstock

It was on London’s junior stock exchange that Edmonds and Groves turned their assets to cash. A City lawyer, Philip Enoch, helped them do it. His shadowy nominee company was a conduit in a million-dollar kickback scheme – and more than 200 million pounds in mysterious share sales.

Headhunted to take over as chief executive of London-listed African Medical Investments, Peter Botha already knew about its row with his predecessor. Vivek Solanki was in hiding, contesting accusations of fraud. Before putting his name to the contract, Botha wanted assurance that there were no more skeletons in the closet.

In January 2011 he met Phil Edmonds and his lawyer at a restaurant in St James’s, London. The lawyer, Philip Enoch, had for more than two decades been among Edmonds’ closest confidantes, working on the ex-cricketer’s stock market ventures from his offices at Salans, a top London law firm.

“Philip, I'm going to invest two million dollars of my own cash in this company,” he told Enoch, according to Botha’s statement to the UK Serious Fraud Office. “Is there anything I should know about, other than the trouble with Solanki?”

“Enoch's response was short and straight to the point,” Botha testified. “He said: 'Nothing!'”

In truth, Enoch could have told Botha a great deal. Just over a year earlier the lawyer had structured the deal that saw Edmonds, Groves and Solanki rip off African Medical’s investors by three million dollars. He was also the owner of Ely Place Nominees.

Fraud allegations against Edmonds and Groves were handed to the Serious Fraud Office in 2013. SFO

Enoch has claimed that Ely Place, officially a dormant company registered in London, is a “neutral” entity that acts as a custodian for his clients’ shares.

Evidence uncovered by Global Witness suggests Ely Place really served as a front for Edmonds and Groves. It sold off hundreds of millions of shares in their listed companies and was the conduit in a $1.2 million kickback scheme.

As Edmonds and Groves scammed their way across Africa, Enoch was the City enabler who understood the financial system and its weaknesses, and could help them turn their assets into cash.

Deep trust

Edmonds’ ties to Enoch date back to long before his partnership with Groves. They were an odd couple but somehow it worked.

“It was a working relationship of deep trust,” recalls one former employee of Edmonds who knew both men in the 90s, when Edmonds left professional cricket to devote his energy to investing.

“Enoch was a solid sort of man, not flash. Edmonds was lively. He had a huge boardroom table with two phones he would stand in front of it all day, tossing a cricket ball in one hand.”

Edmonds also had a temper: juniors needed sharp reflexes to dodge – or catch – the leather-bound hardwood ball when it came zipping across the office towards their heads, the person said. As the irascible former spin bowler played for high stakes in Africa, level-headed Enoch was the perfect foil.

From early on in Edmonds’ career, Enoch played a crucial role. He has held positions at more than 20 firms set up by Edmonds in the UK over the course of his career, Companies House records show.

The lawyer has also been secretary of all but one of the nine companies Edmonds and Groves have floated on the AIM exchange. Seven of those listed firms have had a relationship with Ely Place.

Ely Place is a tiny firm registered at Enoch’s home address. Enoch owns it jointly with Jeremy Franks, a lawyer who in 2004 was sentenced in the US to 10 months’ house arrest for using offshore companies to help a client hide $9 million.

The company’s current secretary is Christopher O’Connor, Enoch’s former Salans colleague who worked on Edmonds-Groves deals across Africa.

Officially speaking, Ely Place does almost nothing. Registered as dormant, it is forbidden from trading and only has to return rudimentary accounts.

According to stock exchange filings, its role is to hold small numbers of shares in Edmonds and Groves’ listed companies to be handed out to their directors as bonuses.

Dig a little deeper, though, and Ely Place seems to be doing far more than acting as a kind of trustee. It owns the company that holds the lease on Edmonds and Groves’ Mayfair headquarters. It has also been trading shares worth hundreds of millions of pounds.

Colossal sell-off

Global Witness accessed trading records for the four Edmonds and Groves listed companies registered in the UK: Capricorn Resources, Camec, African Platinum and Central African Gold.

(The others, though traded in London, are based in secrecy havens like the British Virgin Islands or the Isle of Man, where the data isn’t published).

The records reveal that Ely Place has been engaged in a colossal sell-off: between 2004 and 2009, Ely Place sold Camec shares with a market price of £152 million.

And from 2003 to 2007, it disposed of African Platinum shares worth £46 million at market price, a Global Witness analysis of data from UK Companies House and Bloomberg shows. More sales from Central African Gold bring the total to £211 million (around $340 million).

Where did the proceeds go? They weren’t channelled through Ely Place, according to the firm’s accounts at Companies House. Two sets of evidence – one from a scam in Africa and the other from a court case in London – suggest the beneficiaries of Enoch’s fire sale could have been Edmonds and Groves themselves.

(Enoch told Global Witness that “on rare occasions” the two businessmen benefited from the sales and that had “no intention of discussing other clients of Ely place”.)

The first set of evidence centres on African Medical Investments, a company that from the outset was never quite what it seemed.

When Edmonds and Groves floated it in June 2008, investors were only getting half the story. Away from public view, Edmonds and Groves were negotiating a secret side deal to pay them a $1.2 million dollar kickback.

The scam was almost identical to their Maputo property fraud the following year: using investors’ cash to buy an anonymous company secretly linked to them.

Secret holding

It worked like this: African Medical had a deal to buy Vivek Solanki’s business, which ran private hospitals in South Africa and Zimbabwe. Instead of purchasing the assets directly from Solanki, they arranged with him to set up a new offshore firm with management rights to the clinics.

Solanki’s lawyers incorporated VIP Healthcare in Mauritius. Then they secretly assigned a one-sixth stake in the company to the duo, the leaked documents show.

In August 2008, an African Medical accountant sent Edmonds, Groves, Enoch and Solanki a diagram illustrating the split. “Andrew and Phil” are allocated a 16% stake in VIP – marked as “BVI Mauritius – it shows.

“Today you have advised me that the shareholding is to be as follows,” wrote Solanki’s lawyer after he forwarded it to her. “Your trust, 81%; Andrew/Phil 16%.”

When African Medical bought VIP in December 2008 with money it had raised on the stock market, investors had no idea that a sixth of the purchase price was heading straight back to Edmonds and Groves. And it was Enoch’s job to channel the pay-off.

A leaked letter shows how he did it. Solanki was paid in African Medical shares, deposited with Ely Place for safekeeping.

In a secret side deal, Solanki’s Mauritius-based adviser then wrote to Ely Place to confirm that one sixth of those shares – worth $1.2 million at the time of VIP’s sale – was to be disposed of “as Philip Maurice Enoch may direct at his sole discretion.”

The share payment was designed to give Edmonds and Groves a bigger holding in African Medical than they publicly disclosed – a breach of market rules. Regulations forbid directors from selling stock in the year following a listing.

But with Enoch as cover, they could trade or hold their secret stake as they chose.

Global Witness

In a written reply to Global Witness, Edmonds and Groves did not answer questions on the VIP Healthcare deal. Enoch said the transaction wasn’t a kickback.

“It is completely untrue that one sixth of VIP Healthcare and/or one sixth of the consideration shares was assigned to Mr Edmonds and Mr Groves,” Enoch wrote to Global Witness, saying that a portion of the shares had been put aside for incentive payments to managers.

“I did not believe then that this transaction was fraudulent in any way and that remains my view to this day.”

It was “a fraud on African Medical and its shareholders”, Solanki was advised by Charles Samek QC, a leading UK lawyer, according to a February 2011 email seen by Global Witness. Samek declined to comment for this report.

"I will hold the shares as instructed"

The African Medical deal may point to a deep connection between Ely Place and Edmonds and Groves – but four years on, Enoch would deny it in court.

In late 2011, South African mining boss Heine van Niekerk, who had worked with Edmonds and Groves in Liberia, was hoping to complete the sale of his firm Southern Cross to the duo’s AIM-listed Sable Mining.

Sable had bought half of Southern Cross the previous year and looked set to buy the rest. To guarantee that he wouldn’t sell the remaining shares to anyone except Sable, van Niekerk agreed to put his half of Southern Cross in trust.

It was then that Philip Enoch stepped in to help.

“Transfer them to my nominee company Ely Place Nominees Limited and obviously I will hold the shares as instructed,” the lawyer, who was acting for Sable on the deal, wrote to van Niekerk on 20 October 2010.

Van Niekerk agreed. After all, Enoch was a respectable solicitor and Salans was a big firm. The shares still belonged to him and if Sable decided not to buy the second half of his company, he would get them back – or so he thought.

By the end of the year, Sable had made no move for the shares and it was clear that the Southern Cross deal was off. But when he asked for all of his shares back, Enoch and Ely place refused.

It didn’t take van Niekerk long to realise he had a fight on his hands. By January 2012 van Niekerk’s relations with Sable had soured to the point that he became the target of Groves’ security agents (see Chapter Six: The Spies).

Over the coming months, his house would be bugged, a Sable employee would try to hack his computer and an ex-convict would claim he had been hired by Sable to kill him, according to testimony and evidence from van Niekerk and others.

As he fought Ely Place for his shares in the High Court in London, van Niekerk would also discover that Enoch and his nominee company had no intention of really acting as neutral trustees of the shares. In his witness statement, the Salans lawyer performed what seemed to van Niekerk an astonishing about-face.

“When I said ‘obviously I will hold the shares as instructed’, I was referring to instructions to be provided to me by my client, Sable,” Enoch told the court.

That was news to van Niekerk. The sale agreement was clear that Sable was purchasing only 51 per cent of the shares of Southern Cross, and in stock exchange announcements Sable had never said it owned more.

Suddenly Enoch was claiming a much bigger stake in the company belonged to Edmonds and Groves’ firm.

Failed gambit

Ely Place was colluding with Sable to take his shares, van Niekerk told the court. But Enoch countered that Ely Place was a neutral player “caught between two competing parties, each of whom claims to be the true beneficial owner of the shares.”

Whenever Edmonds and Groves conned investors in their quest for African assets, Enoch and the big-name law firm Salans were on hand in London. The lawyer’s shadowy firm, Ely Place, facilitated deals that swindled investors –all the while selling off shares in Edmonds and Groves’ listed companies worth £211 million.

It didn’t work. Sable was added to the case and Ely Place remained a defendant. In November 2012 both of them quietly settled out of court, handing van Niekerk his shares back.

It wasn’t just the van Niekerk case that saw Ely Place entangled in a dispute over shares. When Solanki tried to claim his stock in African Medical after resigning as chief executive, Enoch refused to hand it over, stoking a dispute in which Solanki and his family \– like van Niekerk – became targets of intimidation.

Enoch told Global Witness that he held on to the shares to protect African Medical after it accused Solanki of misappropriating funds. A 2010 auditor’s report suggests the chief executive manipulated supply contracts. A South African prosecutor declined to pursue a criminal complaint against him.

Ely Place also fought a US court case with a Rwandan lawyer who claimed Enoch had withheld his shares in Edmonds and Groves’ White Nile. Enoch argued the shares were put in trust as an incentive for services that were never performed – and that he was acting on Edmonds and Groves’ instructions.

(Litigation documents suggest the case was settled out of court. Global Witness was unable to reach the lawyer, George Rubagumya, for comment.)

Whenever Edmonds and Groves conned investors in their quest for African assets, Enoch and the big-name law firm Salans were on hand in London. The lawyer’s shadowy firm, Ely Place, facilitated deals that swindled investors – all the while selling off shares in Edmonds and Groves’ listed companies worth £211 million.

If anyone knows where the money went, Enoch does.

Solanki set up VIP Healthcare in Mauritius. Edmonds and Groves had a secret stake. KAM via Getty

South Africa: The Spies

Sable's contacts with South African intelligence chiefs helped him get close to Alpha Condé as he ran for the presidency in neighbouring Guinea. Global Witness

Phil Edmonds has “a remarkable gift for enmity,” his biographer wrote when he was still a cricketer. So does Andrew Groves. Business partners who fell out with the duo found themselves the victims of spying and intimidation.

As Sailor van Schalkwyk approached the target, he realised normal surveillance tactics would not suffice. The high-walled property in Johannesburg’s affluent Inanda district was closely guarded.

Beating a quick retreat to Rosebank a few minutes across town, he secured the services of a street prostitute. While she kept the guard busy, van Schalkwyk slipped quietly past to complete his reconnaissance.

Albertus “Sailor” Van Schalkwyk, whose version of events comes from a sworn affidavit, is not someone you would like to meet alone on a dark night. Reportedly a veteran of apartheid South Africa’s Koevoet torture squad and once a mercenary in Iraq, he later did jail time for drug-smuggling in New Zealand.

In 2011 he was with notorious Cape Town mobster Cyril Beeka on the morning he was shot. The following year he was working for new bosses: Phil Edmonds and Andrew Groves.

The duo had a problem that needed taking care of: a share dispute with another Sable Mining executive, Heine van Niekerk, had turned sour. There had been talks but he was not responding to their persuasion.

On 23 February 2012, van Niekerk arrived at his Johannesburg office to find a man he had never seen before, Wayne Stoltz, announcing himself as Sable’s new head of security, with orders to escort him from the premises.

Ex-mercenary Sailor van Schalkwyk filed a picture of van Niekerk in a handwritten dossier headed "target". Global Witness

Like other enemies of Edmonds and Groves, van Niekerk would remember his first encounter with Stoltz. It was the start of an increasingly unpleasant relationship.

“Be afraid,” Stoltz told him later in a text message, van Niekerk claimed in a court submission. “Be very afraid.”

Stoltz told Global Witness in a telephone interview that he does not recall sending the message.

For now, there was nothing for van Niekerk to do but go home. On Groves’ orders, Stoltz had removed the computer servers, effectively shutting down the office, and upstairs in the boardroom van Niekerk found a director firing the firm’s employees.

Before leaving the building for the last time, van Niekerk made sure to grab the back-up servers, depositing them with the company’s lawyers for safekeeping.

Four days later, Stoltz emailed a photograph of van Niekerk to an intermediary, who forwarded it to Sailor van Schalkwyk, according to a court filing. The former mercenary filed it in a handwritten dossier headed “Target”.

"A small, rectangular device"

Sable’s ties to van Niekerk went back to Liberia in 2010, when Edmonds and Groves had bought into his companies, Delta Mining and Southern Cross.

Van Niekerk’s network in the country gave them access to top Liberian officials and he quickly became embroiled in Sable’s bribery. His contacts with South African intelligence chiefs helped Sable get close to Alpha Condé as he ran for the presidency in neighbouring Guinea.

Now Sable was on the verge of a deal to increase its holdings in van Niekerk’s firms. In January 2012, Edmonds summoned van Niekerk to a meeting at the Dorchester Hotel in London, where he “attempted to coerce me into accepting a substantially reduced price” for his Delta shares, van Niekerk said in written testimony for a South African lawsuit.

It was a shareholder dispute that should have been settled in court. But for Edmonds and Groves, it was personal.

At 7am on 23 February 2012, a day after evicting van Niekerk, Stoltz was at the Intercontinental Hotel at Johannesburg’s OR Tambo Airport for an early briefing. Andrew Groves had just arrived on the overnight flight from London. It was a chance for Stoltz to introduce the boss to Sable’s newest recruit, Sailor van Schalkwyk.

“Groves told us that he wanted to destroy Heine van Niekerk, as he had destroyed others,” van Schalkwyk testified.

In a disciplinary inquiry brought by Sable against van Niekerk, and later in a telephone interview, Stoltz confirmed that he worked for Edmonds and Groves and that he had recruited van Schalkwyk.

Van Schalkwyk had brought a friend to the meeting, Sakkie Morkel, a former agent at the Vlakplaas, the apartheid government’s paramilitary hit squad, named after the farm where it was based.

“It was agreed that we would work with Stoltz, who will instruct us via Groves,” van Schalkwyk said. “Stoltz instructed us to keep surveillance on Heine van Niekerk at all times and report back to him.”

Talking to Global Witness, Stoltz said he attended the meeting with Groves at the InterContinental but didn’t recall bringing van Schalkwyk.

Sakkie Morkel’s wife told Global Witness that he was in hospital and not available for interview. She confirmed that her husband and van Schalkwyk were old friends and that Morkel had been offered work by Stoltz, though she didn’t know if he accepted.

Days later – with the help of the Rosebank prostitute – van Schalkwyk was staking out van Niekerk’s high-security home. His breakthrough came a couple of weeks later: van Niekerk had put his house up for sale and was holding an open viewing. All van Schalkwyk’s team had to do was pose as prospective buyers.

It was on the afternoon of 26 March that van Niekerk’s wife stumbled across the strange little box.

“Sitting at my desk in the study, I found a small, rectangular black device with wiring and two metal antennas,” Kristin Keely Roberts, a US attorney, said in a sworn statement.

Roberts telephoned van Niekerk, who rushed home and searched the house. A similar box was attached to the underside of the bed in the master bedroom, he testified.

“The first show day was used to do inspection of the property in order to establish the best positions of the devices, which functioned via a cellular transmission signal,” van Schalkwyk said later in his affidavit.