Executive summary

The UK introduced the world’s first fully open register of the real owners of its companies in 2016, leading the world in the fight against corruption.

While the register has the potential to make it much more difficult for criminals and the corrupt to launder dirty cash through UK companies, new Global Witness analysis reveals significant issues with ensuring data quality and compliance.

To tackle this problem, Companies House needs clear responsibility and more resource to police the register, enabling it to fulfill its potential to fight crime.

What we did

Working with a group of volunteer data scientists at DataKind UK, Global Witness analysed the data looking for mistakes and suspicious signs, while also comparing information in the register with other datasets.

This provided us with an unprecedented overview of UK company ownership today and allowed us to identify loopholes, information gaps and suspicious activity.

What we found

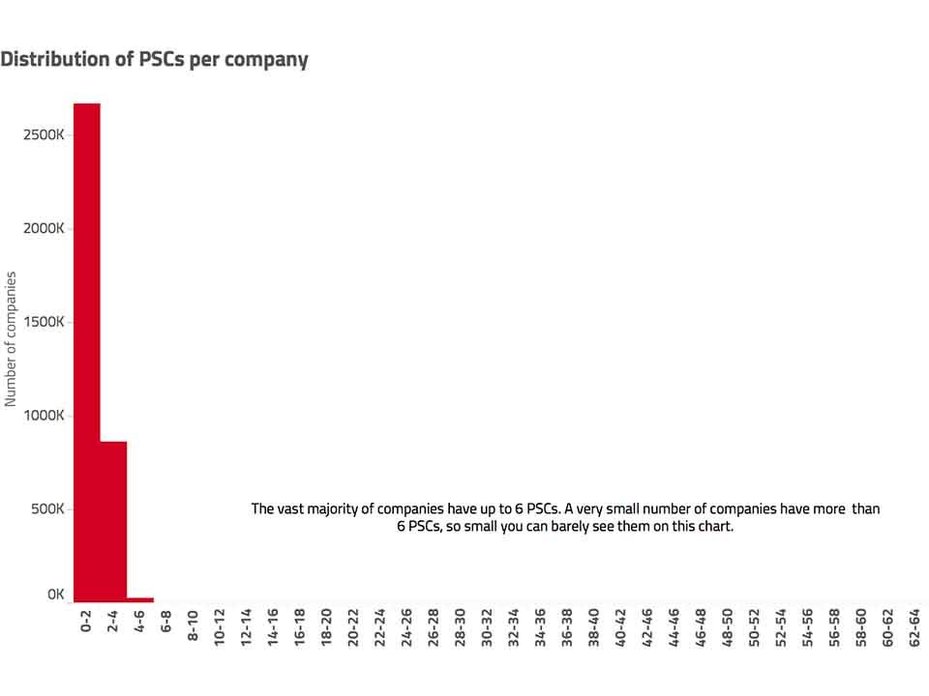

For most companies registering their beneficial owners – known as Persons of Significant Control (PSC) in the UK – is straightforward, with an average of 1.13 beneficial owners for each UK company.

In fact, after two years, 87% – almost 3.6 million companies – of companies are filing at least one beneficial owner.

However, our analysis also reveals that thousands of companies are filing highly suspicious entries or not complying with the rules – problems we never would have found were it not for the open data nature of the register.

Common methods for avoiding disclosure of a company’s real owners include filing a statement that the company has none, disclosing an ineligible foreign company as the beneficial owner, using nominees or creating circular ownership structures.

- More than 335,000 companies[1][2] declare they have no beneficial owner – which is allowed if no individual holds more than 25% of the shares of the company.

- More than 10,000 companies declare a foreign company as their beneficial owner which is unlikely to meet the requirements – of these 72% are linked to a secrecy jurisdiction.[2][1]

- More than 9,000 companies are controlled by beneficial owners who control over 100 companies.

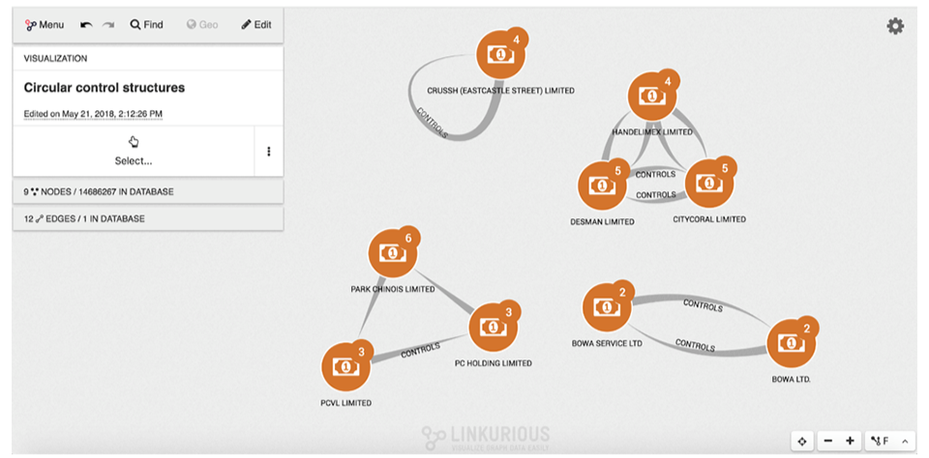

- 328 companies are part of circular ownership structures, where they appear to control themselves.

We also developed an initial red flagging system to help uncover higher risk entries.

While none of these red flags in themselves indicate any wrongdoing, they can inform which companies should be subject to further scrutiny. We found:

- 345 companies have a beneficial owner who is a disqualified director

- 390 companies have company officers or beneficial owners who are politicians elected to national legislatures, either in the UK or in another country[3]

- 7,848 companies share a beneficial owner, officer or registered postcode with a company suspected of having been involved in money laundering

- More than 208,000 companies are registered at a company factory[5]

Recommendations

- The UK Government should clearly mandate and resource Companies House to verify beneficial ownership data submitted to the register and sanction non-compliance.

- Companies House should develop a capability to identify and investigate suspicious activity revealed in the data, in coordination with other relevant Government departments.

- Loopholes for suppressing beneficial ownership information need to be closed, including by making it more difficult to file statements saying there is no beneficial owner and checking up on companies that are listed as the controlling entity.

Global significance

These findings come at a critical time as a growing number of countries commit to similar registers, highlighting the need to create verified open data registers from the outset.

As demonstrated with this analysis, there are huge public dividends for making beneficial ownership information available as open data, not least helping to deter and detect crime and restoring public trust in UK companies.

By acting on the problems revealed in this report, the UK can create a model beneficial ownership register that can guide other countries.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the volunteer team at DataKind UK. Without your dedication, skills and perseverance this analysis would not have been possible.

We would also like to thank Companies House and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) for their constructive collaboration, as well as our colleagues at Transparency International UK (Ben Cowdock, Steve Goodrich) and OpenOwnership (Zosia Sztykowski) for their insights and support in reviewing sections of this briefing. [2]

Acronyms

BEIS: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

BVI: British Virgin Islands

FATF: Financial Action Task Force

GDP: Gross Domestic Product

HMRC: HM Revenues and Customs

LLP: England & Wales Limited Liability Partnership

LP: England & Wales Limited Partnership

NCA: National Crime Agency

PSC: Persons of Significant Control

RLE: Relevant Legal Entity

SLP: Scottish Limited Partnership

TJN: Tax Justice Network

Introduction

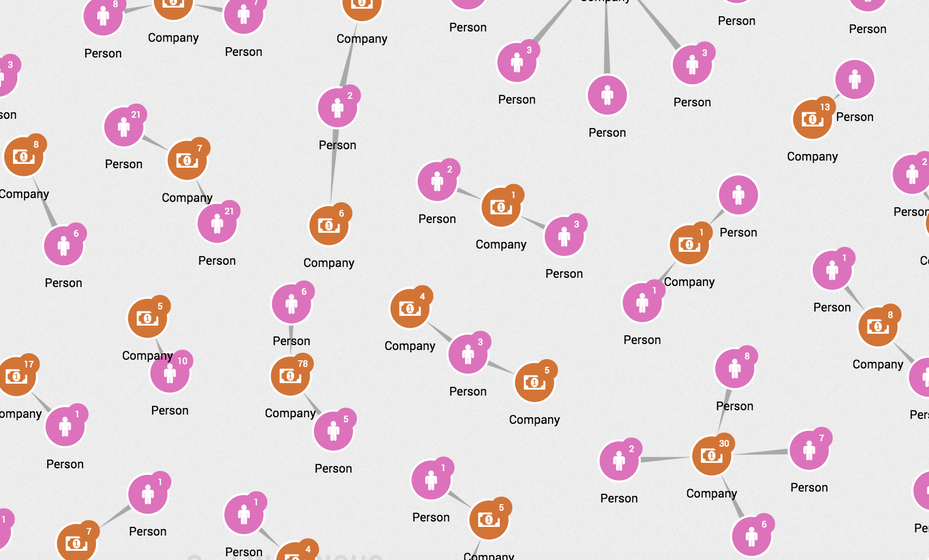

It is quick, easy and relatively cheap to create layer upon layer of anonymous companies spanning multiple jurisdictions. Linkurious

What we set out to do

In 2016, the UK led the world by creating the first fully open register of the people who own and control UK companies – known as Persons of Significant Control (PSC).

By making the register available as open data, the UK Government signalled that it recognised the importance of company transparency for tackling the global challenges of corruption, money laundering and other crimes.

However, this analysis by Global Witness finds that the real people behind thousands of companies are still going unidentified and data is not subject to sufficient scrutiny.

In the largest-ever analysis of the data on PSCs of UK companies, Global Witness and collaborator DataKind UK looked into more than 10 million corporate records from Companies House.

We used cloud computing to analyse and combine the PSC data with other datasets (e.g. on politicians, company officers), and ran analytical scripts to identify mistakes and suspicious filings.

This has given us a wealth of information on UK company ownership and helped answer the following questions:

- What does control of the average UK company look like?

- What is the quality of the data in the PSC register?

- What is the extent of non-compliance with the register?

- What are the remaining loopholes for hiding company ownership?

Given the average UK company only has 1.13 PSCs, registering PSCs should be a straightforward task for most companies.

Yet, while the vast majority of companies are complying, our analysis shows that loopholes in the rules and a lack of checks by Companies House on information submitted undermines the potential of the register to detect and deter crime.

These findings come at a pivotal time for the UK. There is a planned review of the register in 2019 and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is currently assessing the UK's ability to protect its financial system from abuses.

As the first fully open register of its kind, this assessment of the UK’s PSC register also has wider global significance, and can help inform other countries planning to set up similar registers.

All EU Member States will be required to set up public registers of beneficial owners of companies as part of recent revisions to the EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive, which take effect this summer.

In addition, recent developments in the UK will mean that UK Overseas Territories will have to set up similar registers.

In fact, at least 43 jurisdictions are required to or have already implemented a public register of beneficial ownership for companies.[6]

This makes it increasingly important to take stock of progress so far – and, crucially, to highlight areas for improvement in the UK and across the world. That is what this report aims to do.

Persons of Significant Control: The UK Government refers to people who ultimately own and control companies as Persons of Significant Control. Internationally, such people are commonly referred to as beneficial owners. Under UK rules, an individual qualifies as a Person of Significant Control if they:

- Hold more than 25% of the shares in the company; or

- Hold more than 25% of voting rights in the company; or

- Hold the right to appoint or remove the majority of the board of directors of the company; or

- Hold the right or actually exercise significant influence or control over the company through other means or via a trust, meeting any of the above conditions in relation to the company.

Further guidance available here.

Corporate PSC: A PSC is by definition an individual, but UK and foreign companies may be listed as a controlling entity in the Register if they are both "relevant" (i.e. they exercise control over a UK company, satisfying the criteria for a Relevant Legal Entity) and they are also "registrable" (i.e. the first legal entity in the ownership chain). A Relevant Legal Entity must fulfil one of the criteria for exercising significant control as a PSC and either holds its own PSC register or be listed on one of the relevant stock exchanges (i.e. in the European Economic Area, Japan, Israel, Switzerland, USA). However, our analysis finds that many corporate PSCs listed in the register are not valid Relevant Legal Entities. For the purposes of this briefing, we refer to controlling companies as corporate PSCs, as this is how it appears in Companies House data.

Open data: Digital information that can be freely used, modified and shared by anyone for any purpose (subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness). Open data formats are machine readable, meaning a computer can process them. A scanned PDF document is generally not considered machine readable whereas an Excel spreadsheet is.

Why company ownership matters

Money launderers, corrupt politicians, terrorists, arms traffickers, drug smugglers and tax evaders all rely on two things to move their dirty money: company structures that allow them to hide their identity, and banks and other professionals willing to do business with them.

At the moment both are all-too available. A World Bank study of more than 200 cases of large-scale corruption cases between 1980 and 2010 showed the use of anonymous shell companies in nearly 70% of them.

The current financial system makes it simple to hide and move suspect funds around the world.

It is quick, easy and relatively cheap to create layer upon layer of anonymous companies spanning multiple jurisdictions, resulting in an almost impossible task for law enforcement to track down the real human being behind the money.

Additional secrecy can be achieved by using nominees in place of real owners, and by incorporating part of the structure in a secrecy jurisdiction.

In 2014, the head of the UK’s Metropolitan Police proceeds of corruption unit called anonymous companies “the single biggest obstacle to investigating corruption cases”.[7]

Until recently, almost no information was publicly available on the true beneficial owners of companies around the world, perpetuating the opacity that allows corrupt networks to thrive.

There are serious human and financial costs to money laundering. It fosters corruption and crime, distorts economies, fuels instability, undermines democracies and stalls development, including in some of the poorest countries of the world.

Estimates for the global detection rates of illicit funds are as low as 1% for criminal proceeds, while the seizure rate is thought to be even lower, at 0.2%.

Secrecy Jurisdictions: (also known as "tax havens") According to the Tax Justice Network’s (TJN) Financial Secrecy Index, a secrecy jurisdiction “provides facilities that enable people or entities to escape or undermine laws, rules and regulations of other jurisdictions, using secrecy as the prime tool.”

For the purposes of this analysis, Global Witness has limited the scope to those jurisdictions with a secrecy score of over 60 in the Financial Secrecy Index 2018.[8]

Money laundering in the UK

The UK remains a jurisdiction of choice for criminals who want to launder their money.

As a major global financial centre and the world’s largest hub for cross-border banking, the UK’s money laundering challenge is significant.

The National Crime Agency (NCA) believes there is a realistic possibility that money laundering impacting the UK annually may well be in the hundreds of billions of pounds, according to their 2018 report.

The UK's easy, low-cost and no-questions-asked approach to company formation has exacerbated this problem, making UK companies an attractive proposition for people wishing to make dirty money look clean.

The NCA’s 2018 assessment of serious and organised crime found, “The ease with which UK companies can be opened, and the appearance of legitimacy that they provide, means they are used extensively to launder money derived both from criminal activity in the UK and from overseas.”

Company incorporation happens either directly through Companies House or through Trust and Company Service Providers who create companies on behalf of their clients.

While the 2017 UK Money Laundering Regulations require Trust and Company Service Providers to conduct customer due diligence when incorporating a company, bizarrely Companies House is not considered a commercial business provider and is therefore not required to do so, despite being responsible for 40% of incorporations.

Following years of lax policy towards company formation, there has been a proliferation of ‘company factories’ with thousands of companies listed at a single UK address and little to suggest any meaningful business.

UK companies have been at the centre of some of the biggest money laundering and corruption scandals of recent years, including the Panama Papers and the Russian and Azerbaijani Laundromats. Research from Transparency International UK identified 766 UK corporate vehicles allegedly used in 52 large-scale corruption and money laundering cases accounting for nearly £80 billion.

This comes at a great cost: not only does it affect individuals and countries losing out from corruption, it undermines the UK as a global standard setter and as a reputable place to do business.

The only way to restore public trust in UK companies is to ensure that there is transparency in corporate structures, with no place for criminals to hide.

Why open data matters

The G8 Summit in June 2013 saw world leaders sign the Open Data Charter which recognised the central role open data can play in improving government and governance. Jewel Samad / AFP

There is a growing political consensus that transparency of beneficial ownership can make it harder for people to hide the proceeds of crime and corruption.

The form this transparency should take, however, is a source of contention.[9]

Although all 28 EU countries will be required to set up public registers under new EU rules, there is no obligation for these registers to be in open data format and they could even choose to put this data behind a paywall.

Many other countries, including the US, are not even systematically collecting this information in centralised registers.

Global Witness and others have long argued that the most effective way for beneficial ownership registers to realise their potential and improve data quality is to make it public, freely accessible, and in open data format.

Sharp increase in use of company data

Since paywalls were removed in June 2015, access to UK company registry data has grown exponentially to over 2 billion data searches a year, compared with just over 6 million access requests a year for paid information during 2014-2015.

In April 2018 there was an average of 0.5 million searches a day for PSC information specifically.

This indicates that there is a huge demand for this type of information, far exceeding access through closed information exchange systems.

In comparison, the UK Exchange of Notes arrangements with the British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies shared beneficial ownership information with law enforcement just over 70 times since 2016.

The UK took this route when it made this register the world’s first open data register of beneficial ownership in June 2016.

Open data is information without legal restriction on its reuse – beyond the requirement to attribute the source – and that is made available in bulk in a machine readable format.

Open data registers have a number of advantages over closed systems[10]:

- Open data enables wider use of the data in question, ensuring a broader range of people can benefit from the information. The UK beneficial ownership register is a testament to this fact. As there is no paywall or restriction to use, major internet search engines index the register, enabling the public to easily access individual records without knowledge of how to use the Companies House website itself. Statistics show paywalls were an important barrier to the use of UK company data.

- Open data registers enable thorough analysis of data contained within them, including providing a birds-eye view to assess data completeness and quality as a whole, as opposed to systems where it is only possible to search per record. This is a huge advantage of the UK PSC register.

- Open data systems can improve data quality and reduce the incentive for lying, thanks to the number of people who can scrutinise the information. Without the open data format of the UK PSC register, Global Witness would never have been able to identify potential non-compliance and mistakes. In closed systems – including registers that are ‘public’ but behind a paywall or those that do not support access to raw data – it would be much more difficult to identify these issues.

- Open data registers can be linked to other public interest datasets such as information on politically exposed individuals, sanctions lists or procurement. Combining PSC information with other data sources can enable investigative journalists to undertake public interest research.

- Open data systems, when correctly implemented, allow for the development of a multitude of new tools and systems by civil society and the private sector. In this case, Global Witness used the UK PSC register to create tools tailored to the needs of anti-corruption campaigners and investigative journalists (see Chapter III).

Measuring the impact of the register

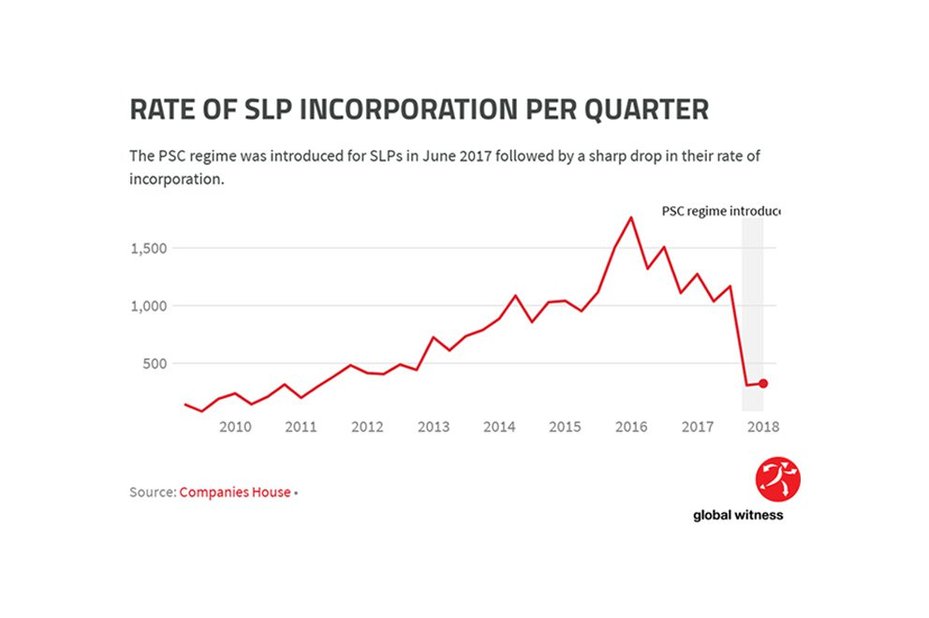

In June 2017, the PSC transparency rules expanded to include Scottish Limited Partnerships (SLPs). SLPs became notorious in recent years for their association with corruption, organised crime and tax evasion.

Until the introduction of the PSC regime, there was no structured data on the beneficial owners of SLPs via Companies House – probably one of the reasons that they were so attractive to criminals.

Since SLPs opened up, rates of incorporation of SLPs have plummeted to their lowest level for seven years, 80% lower in the last quarter of 2017 than its peak at the end of 2015.

This demonstrates the impact that beneficial ownership transparency can have in driving down the abuse of corporate vehicles.

Global Witness

What the data tells us

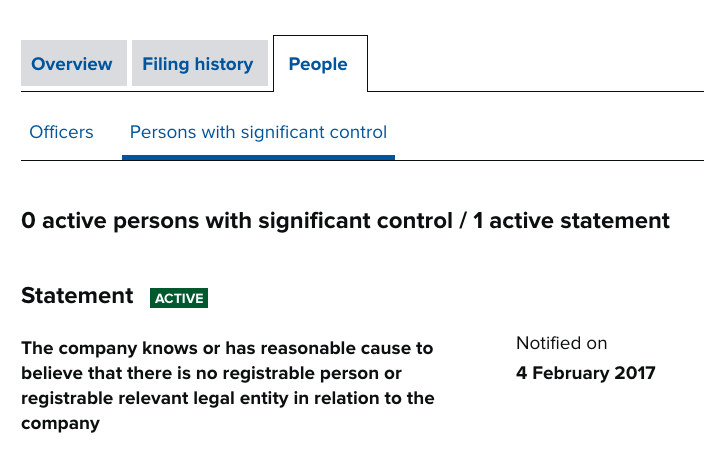

Screenshot of PSC statement. Global Witness

All statistics are based on an analysis of the UK’s Persons of Significant Control register accurate as of 1 March 2018. More information on the methodology and data processing for this project is available here.

Who controls the average UK company?

As of 1st March 2018, the most common nationality for a PSC is British, covering 80% of all individual PSCs.[11]

Almost two years after the launch of the register, 87% of active companies – or 3.6 million companies – to which the PSC regime applies[12] are filing at least one PSC on the register. Of the 13% of companies that have not filed a PSC, not all of these are necessarily non-compliant.

As per the UK’s rules, valid reasons for not disclosing a PSC include companies with more than four shareholders (e.g. where no individual holds at least 25% or more shares in the company).

Only 58 companies claimed a trading exemption, which companies can receive if they have their shares listed on a relevant regulated stock exchange.[13]

However, a number of these seem unlikely – including a small bed and breakfast, which we would not expect to see listed on a stock exchange.

A further 199 individual PSCs have secured the right to keep their details off the public register, on the grounds that they face a serious risk of violence or intimidation. Overall, the vast majority of companies appear to be capable of identifying their PSCs and making them public.

The vast majority of companies have up to six PSCs. Global Witness

Alarmingly though, 35% of SLPs on the register say they have not yet completed the steps to find their PSCs. While the PSC regime has only applied to SLPs for eight months, it is worth asking why SLPs are struggling to comply in such large numbers.[14]

As a point of comparison, six months after the register came into force and before SLPs needed to comply, only 1% of UK companies reported that they had not yet completed the steps to find their PSCs.15

It is unclear why SLPs are not complying, but the well-publicised use of SLPs in recent money laundering scandals makes it a cause for concern.

Taking the PSC register as a whole, as of 1 March 2018, less than 1% of companies reported that they had not yet completed the steps to find their PSCs.

What is the quality of the data in the PSC register?

Almost all government datasets have gaps that reduce data quality and its usability.16 The UK PSC register is no exception. While the PSC data does suffer from some data quality issues, overall the data is good quality and is provided in a way that enables a broad range of people and organisations to make use of it. The issues that we have found include:

- Lack of unique identifiers for individual PSCs, making it less easy to analyse. While the register includes the month and year of birth for an individual PSC, this is not enough in some cases to distinguish between two people, particularly for common names. The use of a correspondence address in combination with month and year of birth to create a unique ID for the PSC may also not be effective, as PSCs often list different correspondence addresses for different companies under their control. This makes it very difficult to accurately assess how many and which companies a given person actually controls. This is a fundamental challenge for investigations using PSC data.

- Lack of standardisation for certain data fields, which would help ensure the data provided is valid and realistic. For example, we found a number of PSCs with impossible or highly unlikely dates of birth, including someone who has not yet been born. Although the number of impossible dates of birth was small, it suggests there may be a wider problem of data validation. We found similar issues with misspellings and inconsistencies in both the nationality and address country fields, making it hard to summarise information using these fields. Companies House has since addressed this issue by introducing data validation from the outset in the new incorporation form, using age prompts and restricted menus rather than free text input fields.

Potential non-compliance and loopholes in the PSC register

Companies House claims that around 1.5% of active companies are not currently complying with the PSC legislation. This figure primarily reflects the number of companies under the PSC regime who have not submitted any information to the PSC register. In many cases, this is because they have an overdue confirmation statement.

However, based on our analysis, there is likely to be a far higher proportion of companies that are not complying with the law. This includes cases where people have misunderstood what it means to be a PSC, which should decrease over time.

While it is impossible to put an exact number on it, we looked at a set of likely indicators for PSC non-compliance. We found at least four ways in which individuals may be suppressing information on who really controls companies, which requires further investigation by Companies House.

1. Filing a statement saying that a company has no PSC – Companies can say they have no PSC without any supporting evidence or checks by Companies House. In total, 335,010 companies have filed statements saying they have no PSC. While many companies legitimately fall into the category of having no qualifying PSC (e.g. because they have five or more shareholders), there is reason to believe that some companies may be using these filings to avoid disclosing their true owners. The fact that Companies House does not currently question these filings means they could be a way of skirting the law.

Companies at some registered addresses appear to be using this technique very frequently.

To explore the extent, we examined addresses where more than 100 companies were registered – often a sign that company service providers run a company. On average 3% of these companies declared that they did not have a PSC, though at some of these addresses, 99% of the companies registered there claimed they had no PSC.

Such addresses are clear outliers and warrant further attention by Companies House.

As we outlined in our report , between 2008 and 2010 four UK companies acquired a collection of leasehold and freehold properties on Baker Street, two properties near Hyde Park and one in Highgate, worth just over £147 million in total.

The properties were held in a corporate chain that included the following UK companies: Farmont Baker Street Limited (“Farmont”); Dynamic Estates Limited (“Dynamic”); Parkview Estates Management Limited (“Parkview”) and Greatex Limited.

All of these companies were controlled by the same British Virgin Islands (BVI) company, which changed its name almost every year from 2008 until the date of the report (July 2015).

2. Naming a foreign corporate PSC that is registered in a country that does not have an eligible stock exchange – The PSC regime allows companies to claim their PSC is a foreign corporation as long as they are listed on ”regulated markets”. Yet we found 10,150 companies that list a corporate PSC not registered in any of the eligible countries.[16]

In fact, nearly three-quarters (72%) of these foreign corporate PSCs are registered or have a correspondence address in a secrecy jurisdiction. By definition, secrecy jurisdictions have low levels of corporate transparency, resulting in little or no public information on company owners.

As a result, thousands of UK companies still have their ownership obscured through companies in secrecy jurisdictions, which is exactly what the PSC register was meant to overcome.

3. Disclosing a person as the PSC who is also a PSC for hundreds of other companies – Our analysis shows that over 9,000 companies are controlled by individuals who control more than 100 companies.

We have found one individual, Michael Gleissner, who controls more than 1,000 companies. While there may be legitimate explanations for why one person controls a very large number of companies, it suggests some individuals could be acting as "nominee" PSCs in place of real owners.

The whole purpose of the PSC regime is to reveal the real owners of companies, making the appearance of possible nominees problematic.

However, while the PSC regime may still have weakness with respect to nominees, it has forced many companies who previously made extensive use of nominee directors to disclose much more detailed data on who really controls them.

There are only 31 PSCs who control more than 100 companies, while there are over 800 directors who direct more than 100 companies.[17]

4. Circular control structures – A circular control structure is a group of UK companies that file another UK company as their PSC, with the final company filing the first company in the group as its PSC.

The simplest example of this is where company A files company B as its PSC and company B then files company A as its PSC.

UK corporate law prohibits circular shareholding. Yet we have identified 328 companies on the PSC register that are part of circular control structures.[18]

A sample of circular control structures from the visual exploration tool Global Witness and DataKind UK developed for this project using Linkurious Enterprise. Global Witness

PivatBank ATM, Ukraine. NurPhoto / Getty Images

PrivatBank

PrivatBank is the largest commercial lender in the Ukraine, founded by the Ukrainian oligarchs Igor Kolomoisky and Gennady Bogolyubov in the early 1990s. It handles more than a third of private deposits in the country and services more than 20 million Ukrainians – around half the country's population.[19]

In December 2016, PrivatBank was declared insolvent and nationalised,[20] costing the government more than the entire amount of aid Ukraine has received from the IMF since the 2014 revolution.[21]

PrivatBank now claims that Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov siphoned off an alleged $1.7 billion from the bank through a series of fraudulent loans to shell companies – essentially profiting from the demise of their own bank.[0]

A UK court case has been launched by PrivatBank against Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov, who, they argue, are the ultimate beneficial owners of the shell companies through which money was stolen.[23]

The biggest share of the alleged stolen funds is said to have been transferred to the accounts of three UK companies: Teamtrend Limited ($494 million), Trade Point Agro Limited ($501 million), and Collyer Limited ($721 million).[24]

In 2017, when the UK’s PSC rules had already come into force, all three of these companies claimed that they had “reasonable cause to believe” the companies did not have a PSC.[25]

However, between 21 February and 12 March 2018, both Teamtrend Limited and Collyer Limited listed Ukrainian national Melnyk Serhii as their PSC. Mr Serhii’s correspondence address is in Dnipro in central Ukraine, the city where PrivatBank has its headquarters.

Checks by Reuters found no sign of the companies at their addresses listed in London.[26]

In December 2017, a High Court judge ordered a worldwide freeze on $2.5bn (£1.9bn) worth of the assets held by the former owners.[20] It is worth noting Teamtrend Limited was the subject of a separate UK court case in 2004 involving Kolomoisky.[28]

If the UK’s PSC register worked more effectively, it should be possible to identify the past and current beneficial owners of these three UK companies.

The fact that companies already suspected of wrongdoing can claim they have no PSC with no further checks by Companies House presents a glaring loophole. Proof of PSC details and proactive follow-up by Companies House would be an important step in dealing with this problem.

There are wider allegations of wrongdoing at PrivatBank. A Kroll investigation commissioned by the National Bank of Ukraine in 2017 found that PrivatBank had lost at least $5.5 billion as a result of “large scale and co-ordinated fraud over at least a 10-year period” before the state took over.[29]

The analysis also found that 95% of loans issued by PrivatBank went to people related to the former owners of the bank and that the bank had been subject to a “large coordinated money laundering scheme”.[30]

In response to the Kroll report, Kolomoisky said: “It is nonsense, which there is no point commenting on...The main question is where was the money withdrawn to and when? All the rest is fiction."[31]

Kolomoisky and Bogolyubov have repeatedly denied the allegations against them, claiming that the takeover of PrivatBank was politically motivated and that the bank was solvent before it was nationalised.[32]

Big chunks of Baker Street were owned by a mysterious figure with close ties to Rakhat Aliyev, a former Kazakh secret police chief, a Global Witness investigation has revealed. iStock.com / mikkoseppinen

The mystery on Baker Street: Still unsolved

In July 2015, Global Witness revealed that big chunks of Baker Street were owned by a mysterious figure with close ties to Rakhat Aliyev – a former Kazakh secret police chief accused of murder and money laundering.

The property empire included 221 Baker Street – where Sherlock Holmes would have lived had he and his fictional apartment 221b really existed.

As we outlined in our report,[33] between 2008 and 2010 four UK companies acquired a collection of leasehold and freehold properties on Baker Street, two properties near Hyde Park and one in Highgate, worth just over £147 million in total.

The properties were held in a corporate chain that included the following UK companies: Farmont Baker Street Limited (“Farmont”); Dynamic Estates Limited (“Dynamic”); Parkview Estates Management Limited (“Parkview”) and Greatex Limited.

All of these companies were controlled by the same British Virgin Islands (BVI) company, which changed its name almost every year from 2008 until the date of the report (July 2015).

In May 2018, Global Witness checked the PSC register to see what it revealed about the ownership of these companies. We discovered that:

- Farmont, Dynamic and Parkview filed confirmation statements and accounts in 2017, stating that the companies had no PSC.

- The current and former directors of Farmont, Dynamic and Parkview, some of whom could be linked to the Kazakh first family in our 2015 report,[34] remain in place, although the entire network of companies was sold in April 2016 to a real estate company incorporated in the United Arab Emirates.[35] There is no suggestion that this new owner has links to the Kazakh first family.

- Greatex Limited also appears to have been sold to a new buyer in April 2016 – this time to a Nigerian oil and gas magnate who has registered himself as the PSC.

In 2015 Global Witness called for an investigation into these companies, the properties they own and the real persons behind them. The fact that the true owners have not come to light – despite the very clear and very public red flags around these companies – demonstrates a weakness in the PSC system.

If the UK’s PSC register was working more effectively, we would be able to identify the real ultimate owner of Farmont, Dynamic and Parkview and trace whether they had any connections to the previous owner, whose links to the Kazakh first family were established in our report.

But these facts remain shrouded in mystery and will remain so until Companies House stops accepting at face value statements from companies who claim they have no PSC, particularly when they have serious red flags linked to their dealings.

Following Global Witness’ report, in May 2016 the UK Government promised to create a public register naming the owners of all overseas companies that own UK properties.[36] Legislation creating that register is expected to be tabled in early 2019, with the register set to go online by 2021.

However, as the Baker Street properties were nominally owned by UK companies, the names of their real owners should already have been made public.

The people who control the most UK companies

Michael Gleissner (1,193 companies) – Michael Gleissner is a filmmaker, entrepreneur and prolific trade mark filer. Since establishing his first e-commerce company in 1989, he has built up a vast portfolio companies, domain names and trade marks worldwide.

In 2017, the UK’s Intellectual Property Office ordered Gleissner to pay Apple £38,085 for filing trade mark revocation proceedings with an ulterior purpose. Apple’s legal representative claimed Gleissner is a "trade mark troll", “i.e. an individual who abuses the trade mark system by filing oppositions and revocation actions without legitimate commercial grounds for doing so, and for the collateral purpose of extracting revenue from trade mark applicants and proprietors.”[37]

Gleissner rejected Apple’s claims against him, and stated he had never sought any payment related to cancelling trade marks. According to Gleissner, his investment company secures brands for start-ups in the form of trade marks and domain names.

Peter Valaitis (997 companies) – Peter Valaitis is the Managing Director of Duport Associates – a UK company formation agent established in 1997 which is authorised by Companies House to submit electronic incorporations.

According to its website, Duport Associates registers around 10,000 new companies each year. For £14 and in as little as 6 hours, it is possible to set up a new limited company through Duport’s software.

As the vast majority of companies under Valaitis’ control are dormant, it is likely that most of these companies are "shelf companies" – whose sole purpose is to be sold on to customers, as advertised on Duport Associates’ website.

Some of the shelf companies available for purchase through Duport are over 10 years old which, similar to a vintage wine, can bring added credibility. Duport’s website describes this as “pick a flower – not a bud.”

Another possibility is that Duport created some of these companies as part of their service to reserve a specific company name.

Waris Khan (639 companies) – Waris Khan is a former director (2012-2014) of the notorious company service provider Formations House, which was previously registered at 29 Harley Street in London.

A 2016 Guardian investigation found Formations House was home to 2,159 companies, some of which used this address for improper purposes, including defrauding people of their investments.

Waris Khan is also linked to the company D Corporation Ltd (05071883), where he was a director between 4 July 2013 and 25 September 2013.

D Corporation Ltd was made insolvent in 2015 on public interest grounds, after an investigation found it was one of four companies involved in a scam selling “miracle” software falsely guaranteeing profits for investors trading on the London Stock Exchange.

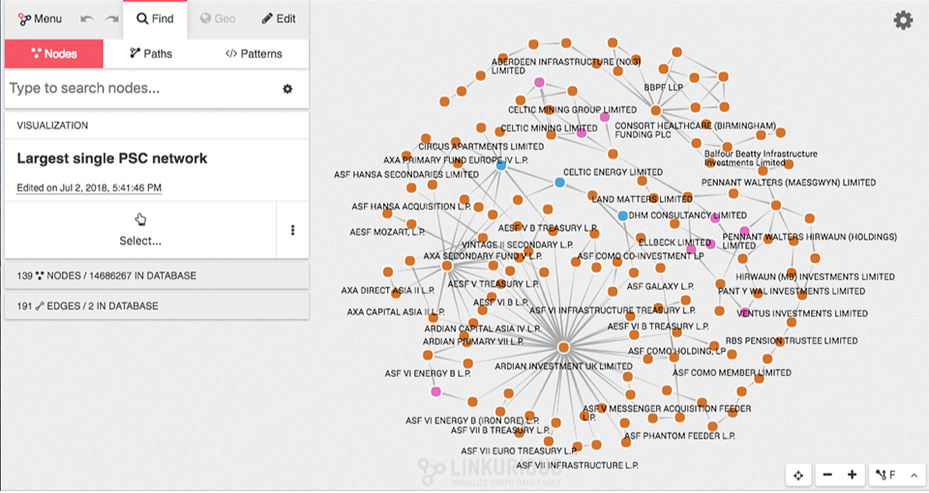

Spinning webs: The networked nature of beneficial ownership

The largest single PSC network of interconnected companies as captured by the visual exploration tool developed by Global Witness and DataKind UK using Linkurious Enterprise. Global Witness

As described above, under certain conditions a company can file another company as a PSC if the controlling entity is a "Relevant Legal Entity".

This means companies in the same corporate group, owned by the same parent company, can avoid making duplicate filings. The data can therefore reveal complicated chains of corporate ownership.

Take for instance the control structure visualised here, which includes a number of private investment firms. The control structure includes more than 100 separate firms, all connected to one another via relationships of control.

If a company at the top of a chain of corporate ownership is either non-compliant with the PSC regime or using one of the methods outlined to suppress information about their true owners, all the companies in that chain will benefit from this secrecy.

The networked nature of beneficial ownership means that, in addition to the 381,052 companies that have filed a "no PSC" statement, another 46,042 companies are part of structures that are ultimately controlled by such companies.

The £10 million smuggling ring and the 700 companies with no PSC

During our analysis of addresses at which a large number of companies are registered, we found that some locations had a particularly high proportion of companies declaring that they had no PSC.

One of these addresses was a business centre in Leeds where 95% of all 1,157 companies registered there said they had no PSC.

761 of the companies declaring they have no PSC were directed by Marc Feldman – a person with two convictions for fraud and tax evasion, partly related to his role in a £10 million smuggling ring.[38] Many of these companies were dormant.[39]

Despite Feldman’s earlier conviction for using companies to defraud others, he was able to maintain a large network of dormant companies making no PSC declarations, raising further questions about the lack of checks on PSC filings.

Companies House and relevant UK authorities should look into this specific case as well as routinely scrutinising companies that have links to individuals with a history of wrongdoing, including via PSCs and officers.

Investigative journalism & the PSC register

During this project, Global Witness built two tools that utilise the readability and bulk availability of the data to support corruption investigations, including by journalists, demonstrating the importance of open beneficial ownership information:

- An automated system for red flagging companies

- A visual tool for exploring the PSC register and other associated public interest datasets

Government and law enforcement could similarly develop investigative tools or techniques that use PSC data to better serve their goals, such as increasing compliance or policing the register.

Towards a system for red flagging suspicious companies

Companies House and other UK authorities face a huge challenge in policing over 4 million PSC filings.

Currently it is difficult to identify suspicious companies among the large number of potentially non-compliant companies (e.g. companies that do not disclose a PSC).

Companies House needs to find a way to sift through these filings and focus its resources on high risk companies, particularly those most likely to be involved in suspicious activity.

With the aim of developing such a system, Global Witness encoded a set of red flags for corruption, financial crime and money laundering based on guidance from international standard setters, the UK Government, and past Global Witness reports.

The red flags do not in themselves indicate any wrongdoing by a company, but should serve as a starting point for further due diligence.

After encoding the red flags as additional fields in the PSC dataset, we ranked companies according to the sum of their scores across the red flags.

We found 2,682 companies had three or more red flags present, suggesting they would merit further investigation.

Global Witness’ pilot demonstrates that automated approaches for red flagging suspicious companies are relatively straightforward to develop.

The system uses only existing open-source technology and publicly available data on UK companies implicated in previous money laundering scandals.

Financial institutions increasingly use similar, more sophisticated systems for due diligence and risk analysis,[40] while Companies House has yet to adopt them.

This could be a way for Companies House to identify companies requiring additional scrutiny and help detect UK companies used for criminal purposes.

Analysing and visualising networks of UK company data

The second tool Global Witness created in partnership with DataKind UK was a visual tool for exploring the PSC register and other associated datasets.

While Companies House offers a web interface for searching the PSC information, this tool allows for ways of using the data that the original website does not cover. Here are some examples:

- Identifying patterns – Some loopholes only manifest themselves as patterns. The clearest example of this is circular ownership structures, as explained above. In addition, the PSC tool introduces the possibility of asking not only which entities directly control a company but also which entities exercise control via other companies. We have seen how some of the issues with the current UK register – such as foreign corporate PSCs which are unlikely to be listed on a relevant stock exchange – are more extensive when relationships of indirect control are considered. If you want to find and quantify the extent of indirect control, it is useful to employ database technologies that naturally focus on the relationships between entities. So-called “graph” or “network” databases lend themselves to this type of enquiry.

- Exploring relationships – Relationships between a large set of individuals, companies and addresses can be complicated. An interactive visual interface can enable the user to identify connections they might not otherwise have found using the simple web search interface or table. We used a tool called Linkurious, which sits on top of Neo4J – a widely used graph database technology – to give Global Witness campaigners and our partners’ access to our database and interrogate it intuitively.

- Cross-referencing with other datasets – The searchable database we built incorporated a range of data sources including the Tax Justice Network Financial Secrecy Index 2018 and information on politicians from EveryPolitician.org. Users can navigate seamlessly between the two datasets and explore the business holdings of politicians. For example, this function can help verify financial disclosures from politicians and identify discrepancies.

Nationalities

One example where our PSC research offers new insights relates to the nationalities of PSCs for different corporate entities.

Recent high-profile money laundering scandals, such as the Azeri and Russian Laundromats, involved large numbers of Scottish Limited Partnerships (SLPs).

The findings further support the claims of aggressive marketing of SLPs to people in former Soviet countries, where there are higher perceived money laundering risks.

Politicians

Another way of developing new insights into PSC data is by linking it to different datasets.

As the video above shows, using open data from the website EveryPolitician, which publishes crowd-sourced data on politicians, we could identify politicians who are PSCs or company officers.

We then imported this information into our visual exploration tool (see an example of this at work in the video above).

This tool could be used by journalists to cross-check the financial interests of politicians against what they declare on the Register of Members’ Financial Interests.[41]

Cabinet minister Jeremy Hunt. Rosie Hallam / Getty Images

A UK cabinet minister and a "no PSC" statement

In April 2018, the Guardian and the Daily Telegraph reported that the Rt Hon Jeremy Hunt MP, the UK’s Secretary of State for Health and Social Care, failed to declare his stake in Mare Pond Properties Ltd when it incorporated in September 2017.[42]

The initial incorporation documents claimed the company had no PSC, despite both Hunt and his wife having stakes of over 25% in the company.

A spokesman for Jeremy Hunt said: “Jeremy’s accountant made an error in the Companies House filing which was a genuine oversight ... Although there was no personal gain involved, Jeremy accepts these mistakes are his responsibility and has apologised to the parliamentary authorities.”[43]

While there is no allegation of any intentional wrongdoing by Jeremy Hunt, this case demonstrates the need for more scrutiny of "no PSC statements" by Companies House, particularly when a company is linked to a senior politician, such as a Cabinet minister.

Challenges and recommendations

As the first register of its kind, the UK PSC register is ground-breaking and already serving as an important model for other countries.

Two years into implementation, the strengths and weaknesses of the register are becoming increasingly apparent.

There are several key areas where the PSC register can be commended:

- The register’s availability as open data. As previously detailed, the open data format of the register provides a huge opportunity for law enforcement, Companies House, civil society organisations, journalists and others to analyse the data for mistakes and suspicious behaviour, as we have now done.

- The ongoing efforts to update and improve the PSC rules to close new loopholes. Such improvements include bringing new legal entities within scope (i.e. SLPs) and moving from annual PSC registration to event-driven reporting, as required by the 4th EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive in June 2017. Companies are now required to file changes to PSC within 28 days, giving a boost to proactive compliance and enabling UK authorities to chase companies that are failing to report or are taking too long to identify their beneficial owners.

- A large-scale education drive by Companies House on the new PSC requirements, which should result in a better ability to distinguish between suspicious filings and honest misunderstandings about how to file PSC information correctly.

However, our analysis of the PSC register has also revealed some major gaps hampering the register from achieving what it was set out to do. These include:

- Data validation: Ensuring data entered represents a valid possible entry and is complete remains an important challenge for the register, making it much more difficult to cross-reference PSC data with other datasets. Many of the data-quality issues could be overcome by changing the way data is entered in the first place (e.g. validated UK addresses). As part of a new incorporation form developed with HM Revenues and Customs (HMRC), Companies House has now created a more intuitive process, integrating age prompts and validated nationality and country fields, due to be rolled out by the end of June 2018.

➔ Companies House should integrate additional data validation systems, such as automated checks, UK postal address validation and multiple-choice drop-down menus wherever possible to improve data quality. - Data verification: One of the biggest weaknesses of the UK PSC register is the lack of systematic verification of data submitted – i.e. it is solely self-reported data from companies. Verification is an important step for increasing the accuracy of beneficial ownership information, making it more difficult and risky to lie. It would also in turn help the Insolvency Service and law enforcement agencies investigating financial crime. However, Companies House is not currently tasked with verification of PSC data and there is limited proactive follow-up, increasing the risk of misleading and inaccurate data. Despite this clear need, as of February 2018, the UK Government had no plans to introduce automated verification of beneficial ownership data.

Fortunately, the 5th EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive (2018) introduces new requirements for EU countries to ensure beneficial ownership data is “adequate, accurate and current, and shall put in place mechanisms to this effect.”[44] The new rules also require entities conducting customer due diligence, such as accountants, real estate agents and banks, to file reports with national authorities if they find discrepancies between the information they have and information in the public register. The EU Directive suggests mentioning discrepancies in the register until they are resolved. The UK Government recently stated it would implement the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive, as the 2019 deadline for transposing the new rules falls within the Brexit "implementation period."

In addition to verification as set out in the EU rules, Companies House should take other steps to verify and improve the accuracy of PSC data, such as:

➔ Requiring the submission of proof of identity, which would show that all named PSCs are existing people. Denmark already requires beneficial owners to submit a scanned copy of their passport or other national ID, limiting the possibilities for false registrations. This is a reasonable request, given that proof of identity is also needed when opening a bank account.

➔ Requiring the submission of documents proving ownership or control of the company. This could include proof of shareholding through a company’s confirmation statement or voting rights set out in its articles of association. While this would not necessarily rule out all false disclosures, it would give Companies House a starting point for compliance work – and raise the stakes for those submitting false filings, forcing them to produce some form of fraudulent document.

➔ Cross-checking data against other government datasets, in particular shareholder data, which would help weed out inconsistencies.

➔ Making shareholder data for UK companies available as open data, which would in turn allow this information to be cross-checked with PSC data.

➔ Improving systems for members of the public to report inaccuracies in the register, and publishing statistics on the frequency and outcome of these reports. The feedback form could also be linked to the function to ‘follow’ a company, enabling the reporter to receive updates on actions that result from their submission. In addition, a drop-down menu that sends the report directly to the appropriate team would ensure more effective follow-up, particularly as there is likely to be a big increase in reporting from banks, lawyers, real estate agents and others as a result of the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive.

➔ Increasing opportunities for collaboration with civil society and other relevant stakeholders to improve verification systems and sharing learnings and best practices publicly, especially with other data publishers. - Identifying suspicious companies: One of the most important gaps we have identified is that Companies House does not currently have any system for proactively identifying suspicious companies through PSC data. Our analysis identifies a number of ways in which UK companies avoid disclosure of their PSCs – some of which are illegal under UK rules and should serve as a prompt for further investigation.

We have also found that certain types of corporate entity are less likely to declare their PSCs, notably SLPs and LLPs. Both SLPs and LLPs have a separate legal personality and as such, can themselves open bank accounts or purchase property. In addition, an SLP does not have to file financial accounts if either of its partners is a limited company. With these risk factors in mind, and based on the fact that LLPs and SLPs are known to have been involved in previous money laundering cases, filings from SLPs and LLPs should automatically be subject to further scrutiny by Companies House.

Companies House should also attune to new risks as they emerge. For example, we identified a small but significant uptake in Northern Irish Limited Partnerships and England & Wales Limited Partnerships since SLPs were required to disclose their PSCs (see chart below). As the PSC regime extends to new company types, money launderers will seek to exploit other less well known, and less regulated corporate entities, to which the UK Government should be vigilant.

➔ Companies House should proactively identify and pursue cases of non-compliance, as well as develop a red flagging system to identify suspicious companies for referral to law enforcement.

➔ Companies House should invest more resource into data science approaches for examining PSC data, including experimenting with network database technologies and automated approaches for red flagging suspicious companies.

➔ The PSC regime should extend to include all relevant types of UK companies and partnerships. - Unique identification: As highlighted in the data analysis (Chapter II), the public version of the PSC register only discloses the name, and month and year of birth of the PSC. This can make it difficult to see when several records refer to the same person. This is challenging, both for comparing entries within the register and for cross-referencing the register with other datasets such as lists of politicians, sanctions lists and company officers.

To address this problem Companies House should:

➔ Allocate unique identifiers to individuals, in the form of a number sequence that is specific to the database – not a piece of personal data such as a personal ID or passport number.[45]

➔ Link PSC records with other company datasets held by Companies House, building on existing technology that already links some records for company officers across companies. This would identify individuals who are both PSCs and directors or secretaries of more than one company, as well as help match records against other datasets. - Corporate PSCs: Under the PSC rules, another company can control a company if it is a ‘Relevant Legal Entity’, meaning it should either itself declare a PSC or receive an exemption if listed on a relevant stock exchange.[46] We refer to these companies as corporate PSCs. However, there is no systematic verification of corporate PSCs, even with simple steps such as checking its company number. Similarly, it is possible to file a foreign company as the corporate PSC without having to provide any proof that they are an existing company or their listing on a relevant stock exchange. As a result, there is a clear risk that companies could obscure who controls them simply by listing a corporate PSC.

At the same time, our analysis found only 58 companies filed a trading exemption – a number far lower than we expected, given the many UK companies listed on the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 alone. Of those 58 companies, we found a significant number are unlikely to qualify for this exemption, including, for example, a small inn in Scotland. This raises questions again about the level of scrutiny applied to filings. As of 26 June 2018, Companies House will be able to chase companies regarding this exemption, having allowed a year for companies to update this information voluntarily in their annual confirmation statement. Some of the likely misunderstanding when filings such exemptions will be partially addressed by a more intuitive incorporation form expected by the end of June 2018.

It is also unclear whether a listing on any of the specified relevant stock exchanges – in European Economic Area countries, Switzerland, the USA, Israel and Japan[47] – offers comparable levels of transparency to the PSC register. The rationale for granting exemptions to companies listed on these exchanges was that they already require disclosure of significant shareholdings.[48] However, since the list was originally developed, the PSC register has raised the bar for corporate transparency standards.

➔ Companies House should verify the status of UK companies listed as corporate PSCs by checking the company numbers supplied. To simplify this process, users could select valid entities from a pre-populated multiple-choice list of company numbers.

➔ Companies House should verify the status of foreign corporate PSCs by asking for and checking their company numbers (e.g. through third-party aggregators such as OpenCorporates) and their ticker symbols (an identification code for a stock) if it is listed on a relevant stock exchange.

➔ The UK Government should assess the shareholding transparency provisions for stock exchanges that hold an exemption on the PSC register, and remove the exemption if they do not provide equivalent transparency to the PSC regime. As part of this, the Government should conduct checks on a random sample of cases to ascertain the level of beneficial ownership information that is publicly available through the stock exchanges, with a view to also linking to this information through the Companies House website. - Sanctions: Credible dissuasive sanctions are the only way to ensure companies provide accurate PSC data. In the UK, disclosing misleading or false PSC information to the register, whether deliberate or “recklessly”, may result in a criminal offence and a fine and/or prison sentence of up to two years.[49] Currently, Companies House and other executive agencies refer cases to the Insolvency Service, where the criminal enforcement team prosecutes breaches of Insolvency and Company Law. In Scotland the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service holds responsibility for prosecuting Scottish corporate entities, including SLPs, for breaches of PSC rules. However, so far, no fines have been issued for PSC filings, including for SLPs, and there is no evidence of cases being referred for investigation.

In March 2018, Companies House issued its first prosecution for a false filing of company information, sanctioning Kevin Brewer who had set up fake companies and registered UK politicians as directors and shareholders without their knowledge. Unfortunately, this is not the victory it may seem. Kevin Brewer had set up these companies as a stunt to expose the lack of checks conducted by Companies House during incorporation. He was fined £12,000 and remains the only person to have been prosecuted.

➔ Companies House, the Insolvency Service and the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service in Scotland should enforce sanctions by issuing fines and, where appropriate, prosecuting companies and individuals who are non-compliant with the PSC rules. This should include the large number of Scottish Limited Partnerships who have failed to identify a PSC and are liable for daily fines of £500. - Trusts: When a trust exercises control over a UK company, the PSC register requires the registration of trustees, as well as anybody else who has significant influence or control over the activities of that trust or company.[51] This runs contrary to EU regulations, whose definition of the beneficial owner of a trust is much wider, and automatically includes the settlor, trustee, protector, beneficiaries or class of beneficiaries, and any other person exercising effective control over that trust.[52] It is also inconsistent with the UK’s current register of trusts with tax consequences, held by HMRC. By failing to include specific categories of owners such as the settlor and beneficiaries, there is a real risk of using trustees to obscure the real owners of a UK company.

Trusts present unique money-laundering risks, proving so elusive to track down and prosecute that law enforcement authorities admit to giving up investigations when they come across a trust. As a result, the extent of their use for criminal purposes is critically underreported. The UK Government’s own money laundering assessment found trusts are “known globally to be misused for money laundering”, with overseas trusts presenting particularly high money laundering risks.

➔ The PSC rules should be amended to require the recording of settlor(s), trustee(s), protector(s), and beneficiaries of a trust as PSCs when a trust is identified as controlling a UK company. - Thresholds: The UK only requires beneficial owners to report themselves as PSCs if they control 25% of the shares or voting rights in a company. This high threshold creates a risk that significant interests in a company may not appear in the register, and money launderers will simply be able to structure company ownership so that no shareholding passes the threshold. The result is that deliberate strategies to avoid PSC disclosure may be lost among hundreds of thousands of companies filing that they have no PSC. Global Witness has previously identified examples where owning as little as 10% of a company raised serious red flags, and even cases related to extractive industries where a 1% company stake is worth reporting – where company ownership can be extremely profitable and corruption risks are very high.

Not only is the threshold too high, but there are also challenges resulting from the banding of ownership stakes in a range from 25% to 50%, 51% to 75%, or 76% to 100%. This will always result in an imprecise figure and can make it difficult to compare data across jurisdictions. As the vast majority of UK companies have only up to six PSCs, there is limited additional burden in requiring companies to file a specific percentage.

➔ Ideally, there should be no ownership threshold and companies should be required to report their PSCs’ holdings of shares or voting rights in exact percentages.

Towards a beneficial ownership data standard

As more countries launch public registers of beneficial ownership, consistency in how data is collected and shared is vital to ensure the true potential of this data is realised.

OpenOwnership is an organisation building an open, global beneficial ownership register that will link data from around the world, allowing users to track relationships across national boundaries.

As part of this, OpenOwnership is developing a Beneficial Ownership Data Standard (the Standard), a framework for collecting and publishing beneficial ownership data so that it can be linked across jurisdictions and with other key datasets.

Data published to the Standard is more easily reused and higher quality.

For example, the Standard recommends the use of ISO 2-Digit country codes for nationality and jurisdiction of incorporation, which could resolve some of the registers' problems with inconsistent naming of countries.

The more countries publish to the same standard, the simpler it will become to tell the difference between a data entry error and a genuine red flag.

Jade mine in Kachin State, Myanmar. Minzayar

The importance of unique identifiers: Jade and the Generals

The use of unique identifiers to connect individuals within corporate research can be enormously powerful.

A 2015 Global Witness report revealed the network of military elites, US-sanctioned drug lords and crony companies controlling Myanmar’s multi-billion-dollar jade industry.

Without unique identifiers to connect individuals, particularly in a context where some names are very common, this pioneering analysis would not have been possible.

More fundamentally, there are underlying gaps in the institutional setup and resourcing of Companies House that undermine the effective functioning of the PSC regime:

- Institutional Setup: Companies House is responsible for registering company information and making it available to the public, as part of its statutory role as the UK registrar of companies. With regard to the PSC register, Companies House is responsible for ensuring companies comply with the PSC rules, such as pursuing companies that fail to file PSC information. Companies House is not formally responsible for verifying PSC data – meaning it can to some extent accept PSC statements at face value – and lacks investigative powers. This limits Companies House ability to proactively refer companies and relies on other UK investigative bodies to find and look into suspicious activity revealed by the register.

As a result of its limited mandate, Companies House’s efforts have so far focused more on addressing superficial inaccuracies than on systematically examining the reliability of information. While Companies House has taken some steps to pursue likely non-compliant companies – including writing to 2,500 companies with corporate PSCs in secrecy jurisdictions[53] – this falls far short of a comprehensive approach.

Problems are also apparent in the way Companies House directly incorporates companies. By law, private sector formation agents should not establish a business relationship without having completed customer due diligence, but a legal loophole means this standard does not apply to Companies House. Consequently, Companies House cannot refuse a request to incorporate a company and companies incorporated by them are not sufficiently subject to checks, increasing the risk that UK companies are used by criminals.

In terms of prosecutions, Companies House only has a limited role and mainly deals with cases related to filing of accounts and confirmation statements. The Insolvency Service is responsible for prosecuting the vast majority of offences under the Companies Act, but as mentioned above, has yet to prosecute a single case related to PSC filings.

This all points to the wider problem of a fragmented institutional setup and a lack of political will to capitalise on the opportunity at hand to use the register to detect and deter crime. There is no verification of PSC data, no systematic sanctioning for non-compliance and no method for using the data in the PSC register to identify suspicious filings and generating investigative leads – all opportunities for policing the register that are currently being missed.

➔ The Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy should direct Companies House, under s.1061 of the UK Companies Act, to take all reasonable steps to monitor and ensure compliance with company law –including the completeness and accuracy of PSC submissions. This should clarify that Companies House has direct responsibility for validating and verifying PSC data, both during incorporation and as part of its role in overseeing the register.

➔ The Government should also consider giving Companies House investigative powers to pursue suspicious companies, or ensure this task is carried out by other parts of Government in close coordination with Companies House.

➔ The Government should set up a cross-agency working group to facilitate cooperation and support an effective PSC regime, including Companies House, HMRC, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the National Crime Agency and the Insolvency Service. - Resources at Companies House: Until recently, Companies House only had six staff responsible for policing the 4 million companies on the PSC register. In January 2018, the Government confirmed there are now 20 staff employed to deal with PSC compliance activities. As a point of comparison, there are currently 3,765 staff working at the DWP investigating benefit fraud and error. It is impossible for Companies House to take on more responsibility for verifying data and policing the PSC register without adequate resources. One possible source for funding could be the future income generated from fines for non-compliance with the PSC rules.

➔ The Government should give Companies House more resources, including staff and funding, to carry out thorough verification, identify suspicious activity, and pursue prosecutions related to PSC information.

Collaboration with DataKind UK

The first DataDive looking at the UK Persons of Significant Control data was organised in November 2016. Briony Campbell

The UK Persons of Significant Control register is easy-to-use and searchable for the average user simply wanting to look up a specific company and see who controls it.

All you need is a web browser and an internet connection.

However, analysing this same data presents different challenges. With over 4 million PSCs listed as of 1st March 2018, the data far exceeds the upper limits of what a standard spreadsheet application such as Microsoft Excel can open.

Given the engineering and analytical challenges associated with data of this size, Global Witness sought the expertise of DataKind UK, a non-profit organisation dedicated to using data science for social good.

The analysis presented in this briefing by Global Witness is based on a collaborative effort with a team of volunteer data scientists recruited and managed through DataKind UK.

The first stage of collaboration with DataKind began with a two-day long event in November 2016, almost six months after the launch of the UK beneficial ownership register.

The event, organised in collaboration with OpenCorporates, Spend Network and OCCRP, was used to develop an exploratory analysis of the register.[54]

The insights and investigative leads generated that day were passed onto Companies House, which has since made changes to the register’s nationality field and age prompts, and looked further into 2,500 companies linked to secrecy jurisdictions.[55]

In 2017, the second stage of collaboration with DataKind began, involving a dedicated team of four volunteer data scientists working alongside Global Witness. This resulted in a comprehensive analysis of the data in the UK PSC register, and the development of new tools for exploring the register through a network graph.

The methodology used, codes and steps taken are all described in detail on Global Witness’ code sharing site.

The insights outlined in this briefing were obtained using free software, a small team of volunteer data scientists and Global Witness staff, demonstrating that Companies House could easily find ways of identifying potential non-compliance and poor quality data without incurring large additional costs.

Resource Library

The companies we keep

Download ResourceEnd notes

-

This is data taken from the everypolitician.org dataset, which includes data on politicians from 233 countries in the world. For UK politicians this includes only current Members of Parliament (57th Parliament - House of Commons). See more here.

-

This includes all other EU Member States (27 countries, excluding the UK), members of the European Economic Area (Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein), Afghanistan, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, Ukraine and relevant UK Overseas Territories (Anguilla, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Gibraltar, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands).

-

These jurisdictions include: These include: Andorra, Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Bolivia, Botswana, British Virgin Islands (BVI), Brunei, Cayman Islands, Chile, China, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Curacao, Cyprus, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Gambia, Ghana, Gibraltar, Grenada, Guatemala, Guernsey, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Isle of Man, Israel, Japan, Jersey, Kenya, Lebanon, Liberia, Liechtenstein, Macao, Macedonia, Malaysia (Labuan), Maldives, Malta, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Monaco, Montenegro, Montserrat, Nauru, Netherlands, Panama, Paraguay, Philippines, Puerto Rico, Romania, Russia, Samoa, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Singapore, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Switzerland, Taiwan, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Turks and Caicos Islands, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates (Dubai), Uruguay, US Virgin Islands, Vanuatu, Venezuela. See: Tax Justice Network, Financial Secrecy Index 2018, available at: https://www.financialsecrecyindex.com/introduction/fsi-2018-results

-

Maya Forstater, for instance, puts forward a privacy based argument against open registers in her working paper Beneficial openness? Weighing the costs and benefits of financial transparency, 2017. Available at: https://www.cmi.no/publications/file/6201-beneficial-openness.pdf

-

As discussed later, the current register lets users input the same nationality in multiple different ways such as “British” and “UK”. The figure given here is only for those individual PSCs who have their nationality as “British” and excludes other versions of the nationality that might be considered equivalent.

-

In our analysis we have excluded the following company and partnership types to which the PSC regime does not apply: Industrial and Provident Society, Registered Society, Assurance Company for England & Wales, Overseas Company, European Economic Interest Grouping (EEIG) for England & Wales, Limited Partnership for England & Wales, Assurance Company for Scotland, Overseas Company registered in Scotland (pre 1/10/09), European Economic Interest Grouping (EEIG) for Scotland, Overseas Company regd in Northern Ireland (pre 1/10/09), Industrial & Provident Company, Scottish Industrial/Provident Company, ICVC (Investment Company with Variable Capital), Scottish ICVC (Investment Company with Variable Capital), Northern Ireland Industrial/Provident Company or Credit Union, Scottish Royal Charter Companies, Northern Ireland Credit Union Industrial/Provident Society, Northern Ireland Royal Charter Companies, Royal Charter Companies (English/Wales), Northern Ireland ICVC (Investment Company with Variable Capital), Limited Partnership for Northern Ireland, European Economic Interest Grouping (EEIG) for Northern Ireland, Assurance Company for Northern Ireland, Charitable incorporated organisation, Protected cell company.

-

Based on an earlier analysis Global Witness conducted in October 2016. See Global Witness, What does the UK beneficial ownership data show us?, Nov 2016. Available at: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/blog/what-does-uk-beneficial-ownership-data-show-us/

-

At the time of publication the most recent Open Data Barometer, a global initiative for measuring the impact and prevalence of open data, has highlighted the prevalence of quality issues among open government datasets: https://opendatabarometer.org/4thedition/report/

-

Companies that are listed on a relevant stock exchange are exempt from filing a PSC according to the UK rules. Specifically, companies can file a trading exemption if their shares are admitted on a regulated market in the UK, the European Economic Area or on specified markets in Switzerland, the USA, Japan and Israel. In a very limited number of cases, a corporate PSC could be registered outside the regulated markets but listed on one of the eligible exchanges.

-

Companies House does not make data on officers available as bulk open data. The calculations for nominee officers were made using data supplied to us on officers from OpenCorporates.

-

Reuters, Ukrainian tycoon's sacred cow seized by state, Dec 2016. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-privatbank-kolomoisky/ukrainian-tycoons-sacred-cow-seized-by-state-idUSL5N1ED0VN

-

Financial Times, UK court freezes $2.5bn of Ukraine oligarchs’ assets, Dec 2017. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/4bc2f436-e5d9-11e7-8b99-0191e45377ec

-

New York Times, Questions Surround Ukraine’s Bailouts as Banking Chief Steps Down, May 2017. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/12/world/europe/ukraine-central-bank-valeria-gontareva.html

-

Reuters, Ukraine money-go-round: how $1.7 billion in bank loans ended up offshore, Jan 2018. Available at: https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-ukraine-privatbank-insight/ukraine-money-go-round-how-1-7-billion-in-bank-loans-ended-up-offshore-idUKKBN1FD0GN

-