Did diamond money help buy votes in Zimbabwe?

Revenues from a diamond company jointly owned by Zimbabwe’s ruling party, ZANU PF, and the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) may have been used to buy cotton seed for distribution in rural areas in the run up to the 2013 elections.

The National Reconstruction Group, a front for ZANU PF, part-owned a diamond company

In a crowded committee room in the summer of 2018, Happyton Bonyongwe, the former head of the CIO, seemed relaxed. Fielding questions from the Parliamentary Committee investigating the loss of billions of dollars of diamond revenue, he confirmed that the CIO secretly part-owned a mining company – Kusena Diamonds.

He was perhaps too relaxed. Despite being professionally responsible for keeping secrets, he inadvertently revealed more than he intended: a video close-up of his briefing documents revealed that ZANU-PF also owned a 40 per cent stake in Kusena Diamonds. According to the CIO documents, the party’s interest was held through an entity called the National Reconstruction Group (NRG).

A close-up of the former head of the CIO's briefing documents at the Zimbabwe Parliamentary Hearing into missing diamond revenues in 2018 revealed that ZANU-PF owned a 40% stake in Kusena Diamonds via the National Reconstruction Group.

Bonyongwe did not disclose this information in his oral testimony at the hearing and the NRG can’t be found in Zimbabwe’s corporate registry. Only one reference to it can be found in public online sources: in a presentation given in 2014 by the finance director of Seed Co, a seed company based in southern Africa.

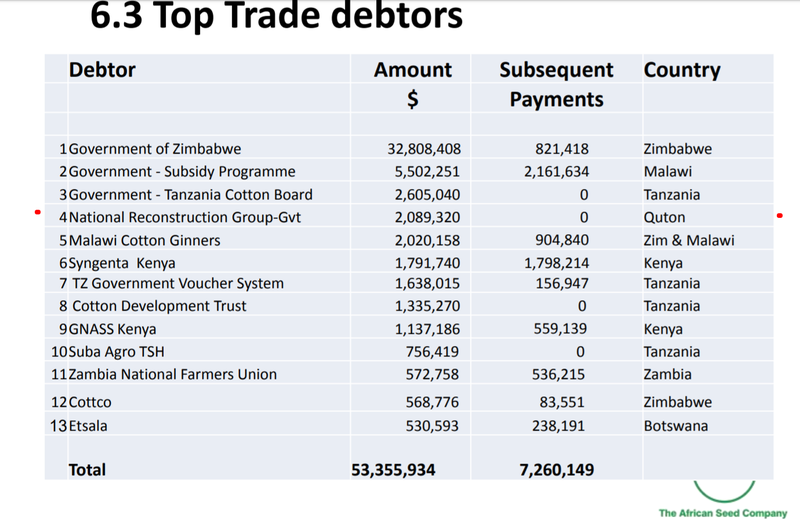

The National Reconstruction Group also appears to have bought cotton seed

A table in the Seed Co presentation from 2014 lists the top trade debtors to the company – including the governments of Zimbabwe, Malawi and Tanzania. Fourth in the table is a “National Reconstruction Group-Gvt”. According to the presentation, in the financial year ending March 2014 the NRG owed $2.1 million to Quton, a subsidiary of Seed Co specialising in cotton seed. When approached by Global Witness Seed Co stated that they had no knowledge of the NRG or its mandate. Quton failed to respond to a request for comment.

Was ZANU PF buying seed to influence rural votes?

Elections in Zimbabwe are rarely free and fair. The 2008 elections were marred by intense violence against opposition supporters: thugs killed over 200 people and thousands more were injured and displaced. There were credible allegations that the 2013 electoral roll was manipulated to suppress the vote in urban opposition strongholds and favour rural areas where ZANU PF has traditionally performed well. In 2018 the end result, a ZANU PF win over a divided opposition, appeared more credible to independent observers.

However, a common thread in all these elections is that ZANU PF exercises control through party apparatchiks and traditional leaders in rural areas – including through preferential distribution of food aid and agricultural inputs. For example, after the 2018 election, the Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission, an official body, upheld complaints about “partisan distribution of farming inputs under the Presidential Inputs Programme, partisan distribution of food aid, threats of violence and intimidation” by ZANU PF elected politicians and local state officials.

Voters in the 2013 Zimbabwe election. ALEXANDER JOE/AFP via Getty Images

From the early 2000s there have been a series of government agricultural subsidy schemes such as ‘Operation Maguta’ (run by the Zimbabwean military), the Presidential Well-Wishers Special Agricultural Inputs Scheme, and the Command Agriculture programme. These schemes are frequently accused of partisanship, with the distribution of seed favouring ZANU PF supporters or even denied to supporters of the opposition.

In recent years, the distribution of seed and other agricultural inputs has been largely managed by various local authorities, ZANU-PF party structures and state organs, including the Office of the President, parastatals and the Zimbabwe Defence Forces.

So if state bodies are already distributing seed in a partisan fashion why would ZANU PF – as a political party – need to purchase seed?

The line between party and state has long been blurred in Zimbabwe. Both insiders and outside observers sometimes find it hard to judge where the interests of the security agencies and government ministries begin, and those of ZANU PF end. Still, this is the first time that a front entity for ZANU PF has been revealed as part-owning a diamond company and having likely purchased cotton seed.

It’s probable that this became necessary during the special circumstances of the Government of National Unity, in power from 2009 to 2013. During this period ZANU PF shared power with the opposition. While ZANU PF still controlled the Ministry of Agriculture and all the security ministries, it lost control of the Ministry of Finance – restricting its ability to fund partisan activities or securocrat priorities. We’ve previously described the motive behind the ownership of diamond companies by the military and CIO as ‘financing a parallel government’.

The then head of Zimbabwe Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) Happyton Bonyongwe (L) with Constantine Chiwenga, then the commander of the Zimbabwean Army, and currently Vice President, are pictured with former President Robert Mugabe in 2008. ALEXANDER JOE/AFP via Getty Images

At the Parliamentary hearing Happyton Bonyongwe alluded to this (at 56 minutes into the video) when describing the reasons for the CIO (also known as the President’s Department) entering the mining sector through Kusena Diamonds:

“The context for investment or participation by a department like the President’s department into mining … is one which really must be understood within the economic context that we were going through as a country at that time ... and there were problems to be funded by Treasury because of the economic difficulties. We, therefore, found it necessary to undertake certain operations that could raise funding to supplement the meagre resources which were coming out of the Ministry of Finance.”

Kusena Diamonds is now defunct but has previously declined to comment.

In this context the purchase of cotton seed by a ZANU PF front entity in the run-up to the 2013 election would make sense. If the seed was subsequently distributed in a partisan way with the purpose of influencing voters, then this could be an offence by under section 136 of the Zimbabwean Electoral Act of 2005. Global Witness believes there are grounds for an investigation by relevant independent authorities of ZANU PF and the National Reconstruction Group into their activities in both the diamond and cotton sectors.

Global Witness does not allege that Kusena executives knew that company revenue might be used to influence elections, nor that seed companies are in any way responsible for the partisan distribution of seed. Repeated requests for a comment from ZANU PF went unanswered.

Public funds appear to have been used to repay ZANU PF’s private debt

To add financial insult to electoral injury, the private debt incurred by ZANU PF when it bought the cotton seed was seemingly repaid from Zimbabwean public funds. One Zimbabwean news outlet reported in November 2013 that:

"President Robert Mugabe’s ZANU-PF party owes Seed Co $13 million, which accrued through quasi-fiscal activities during the four-year tenure of the unity government with Movement for Democratic Change formations. Seed Co said the debt has been inherited by Treasury.

“When we engaged the finance minister after the elections, his assurance was they are in the process of bringing it (the debt) into mainstream government,” said Nzwere [Seed Co’s Chief Executive Officer]."

It isn’t certain whether the ZANU PF party debt was indeed $13m. However, Seed Co’s financial statements support the idea that the NRG debt was inherited by the Zimbabwean taxpayer, rather paid off by ZANU PF or NRG. Instead of paying the trade debt in cash, the Zimbabwean government paid about $24m to Seedco and Quton in Treasury Bills. These are a form of government debt which pays interest to the holder annually and then, after a three- to five-year period, they are repaid in full when payment is made by the Zimbabwean Treasury to the holder, in this case Seedco and Quton.

Former President, Robert Mugabe, hands out maize seed to a Zanu PF supporter at party headquarters in Harare, 2008. Aaron Ufumeli/EPA/Shutterstock

This is made explicit in Seedco’s half year results for 2014. These state that “Accounts receivable [trade debt] reduced by 53% to $34.8m due to debt collections of $24,7m and transfer of $23.9m (including $2.1m worth of treasury bills given to Quton seed company …) due from Zimbabwe.” Global Witness interviews and analysis of Seedco financial reports in subsequentyears confirm that the NRG debt to both Seedco and Quton was eventually paid off by the Zimbabwean taxpayer through Treasury Bills.

Global Witness does not suggest that the repayment of debt through Treasury Bills implies any wrong doing by any seed company.

A threat to Zimbabwean democracy?

Zimbabwe’s diamonds should have benefited all Zimbabwe’s citizens. Zimbabwe’s mineral resources should belong to its people. Instead of bringing in much needed tax revenue to fund schools or hospitals diamond revenues seem to have been appropriated by securocrats and cronies. It now seems diamond revenue may even have been used to help improperly influence elections.

Whether partisan voter influence programmes funded by Zimbabwe diamonds will be a feature of future elections remains to be seen, but history suggests that it is possible.

Regional observers typically focus on intimidation and vote tampering in the period immediately before polling day. In future, they should also keep a close eye on the partisan distribution of state resources. This is particularly true in rural areas, where two-thirds of the electorate live.

The diamond industry also has a role to play. Buyers should ensure robust due diligence is carried out across the supply chain.

Diamonds are one of Zimbabwe’s most precious resources. But great care needs to be taken to ensure they do not end up undermining Zimbabwean democracy.