Pitching for business

Over a crackly mobile phone somewhere in the Central African Republic (CAR), or maybe Cameroon, a dealer is pitching for business. “Yes, it’s scary,” he says, “but in this business, (…) you have to dare.” The business is diamonds and, as he reminds us, “this [CAR] is a diamond country.” (1)

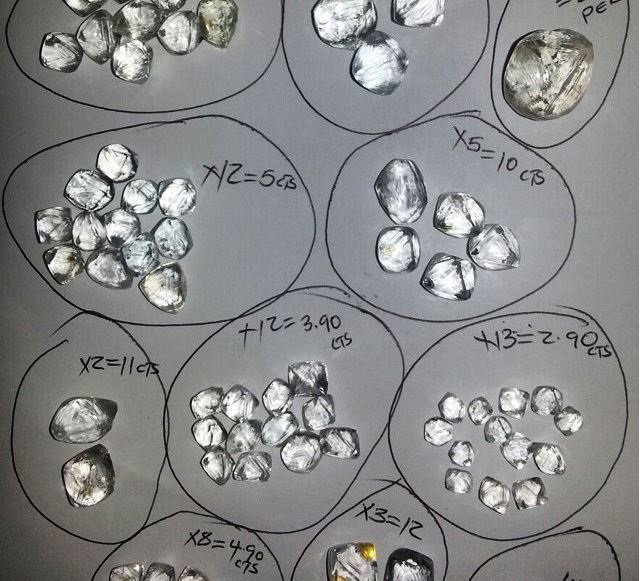

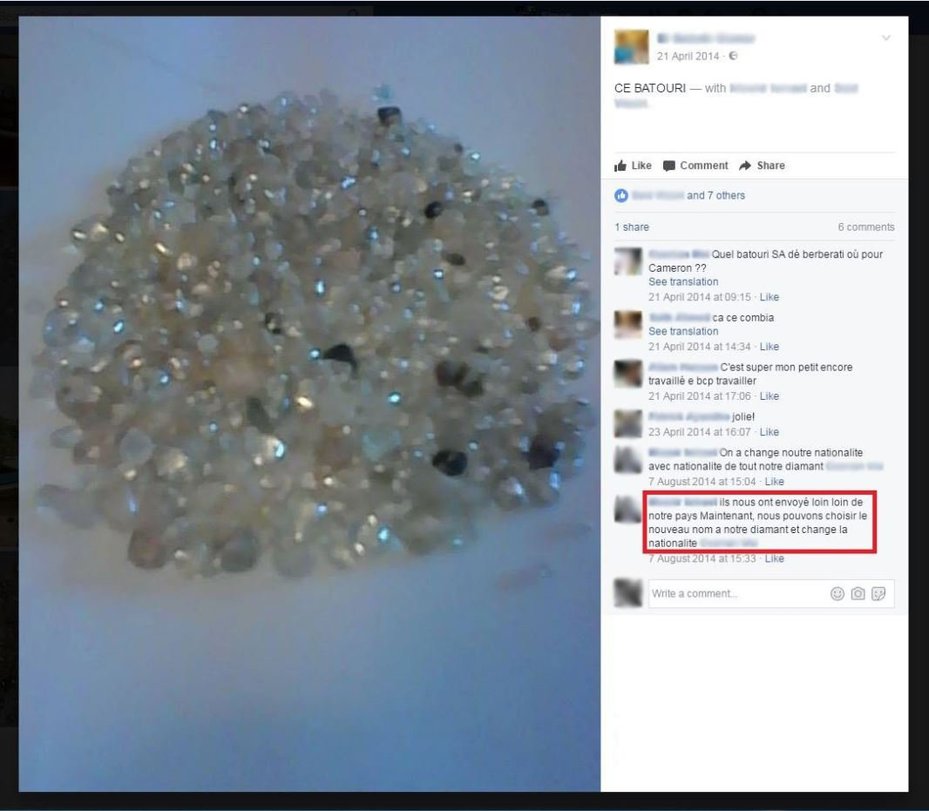

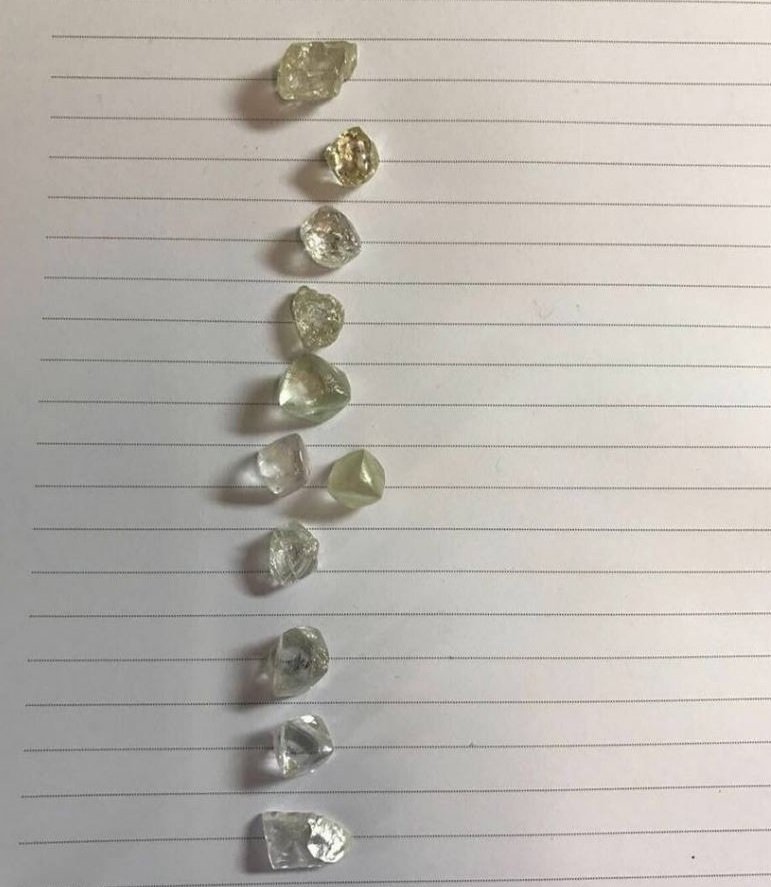

A photo of diamonds sent to us by a trader over Messenger

The dealer knows his audience. He is speaking to an opportunist. Where others see conflict, instability, and chaos, he sees a business opportunity.

“If you come, you are going to see stones. Maybe if you are lucky, a stone will catch your eye” another dealer beckons.(2) All that remains is to find a way to move the valuable stones out of the war-stricken country.

To do so, he needs help. Fortunately there are many ready to offer their services and finding them is easier than ever. Facebook, Messenger, WhatsApp—the tools of the digital economy—are also helping smugglers and middlemen piece together the first steps of the global supply chains that still carry conflict diamonds to international markets.

Posing as one of the many opportunists eyeing a quick profit in some of the world’s poorest and most unstable countries, we spoke to several dealers who promised easy access to CAR’s valuable diamonds.(3) Despite international efforts, CAR’s strongmen and armed groups remain open for business.

“Even where there is war, there are dubious buyers who go to buy [diamonds] and get [them] out in a fraudulent way (…). It is what it is,” one of CAR’s many diamond traders fatefully concedes.(4)

“Traffickers,” he tells us, “go retrieve (…) diamonds towards the rebel side because it’s still much cheaper. We bring them. Often there is a local rebel chief there that hosts them (…). They buy, they buy, they buy (…). Once at the airport [e.g. in CAR or Cameroon], they leave as there are no controls and they pose as simple travelers.”

For those fainter of heart, a different dealer offers an alternative. “If you want to order some diamonds,” he says, we “will send people on motorcycles to, for example, Berberati [in CAR] to pick up the diamonds and deliver them to you [in Cameroon].”(5) As another trader puts it, “we don’t even need to move an inch!”(6)

If diamond smuggling takes a bit of courage, it also takes a head for logistics.

If you come, you are going to see stones. Maybe if you are lucky, a stone will catch your eye.

Young, ambitious, and connected

A game is playing out over the future of CAR’s diamonds. While armed groups and unscrupulous international traders eye a quick profit or the means to buy guns and the loyalty of desperate young men, governments and the diamond industry are looking to enlist CAR’s diamonds in the process of building peace.

We set out to discover how this game of stones is being played, and who is winning.

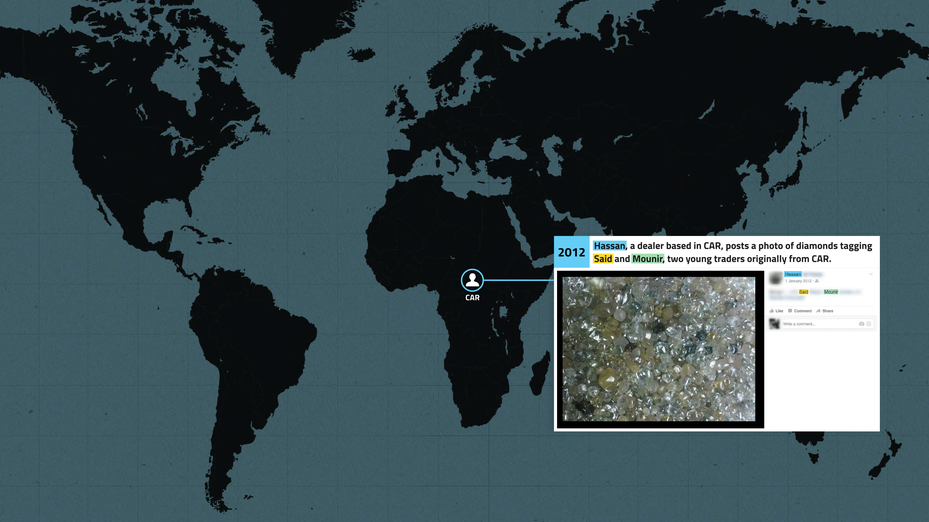

Many of CAR’s diamond traders are young, ambitious, and mobile. Like their peers the world over, they have left their mark on social media. By carefully following the photos and comments through which they chronicle their business and seek new trading partners, we were able to piece together parts of the social media universe they inhabit. Then we joined it.

Posing as an opportunistic international buyer, we used the same social media to join the world of the smugglers, traders, and middlemen that together make up CAR’s diamond markets.

This allowed us to leave theory and frameworks behind and to hear the reality described by those who shape it. Our chats and calls offered an insight into the lives of those closest to the trade, revealing that while international efforts have clearly had some impact, the reality falls well short of the image presented by the international community and diamond industry.

CAR is one of the poorest and most fragile states anywhere in the world. The latest conflict in its troubled history has left over two million people—almost half the population—in urgent need of humanitarian assistance, and displaced nearly one in five.(7) The result has been a humanitarian disaster. CAR ranked second from bottom—187 out of 188—in the 2015 UN Human Development Index.(8) It was last in the 2016 Global Hunger Index.(9)

Yet its rivers and soil are rich in both gold and diamonds. But rather than fueling development, these riches have been plundered by those in power—or those wishing to seize it. Both sides of the conflict have funded their campaigns of violence by drawing on CAR’s diamond wealth.

Efforts to control the flow of CAR’s diamonds and keep them out of the hands of the predatory armed groups currently ransoming the country’s future are falling short. Diamonds from all parts of CAR are finding their way out of the country and on to international markets. Several traders spoke openly of the ease with which diamonds could be smuggled, and some spoke openly of working with international dealers. Many seemed entirely unaware of the restrictions imposed from above. Those who did know of them appeared able to circumvent them with ease.

CAR and its population need a diamond trade. But they need a responsible diamond trade more.

The conflict

It started with a coup.

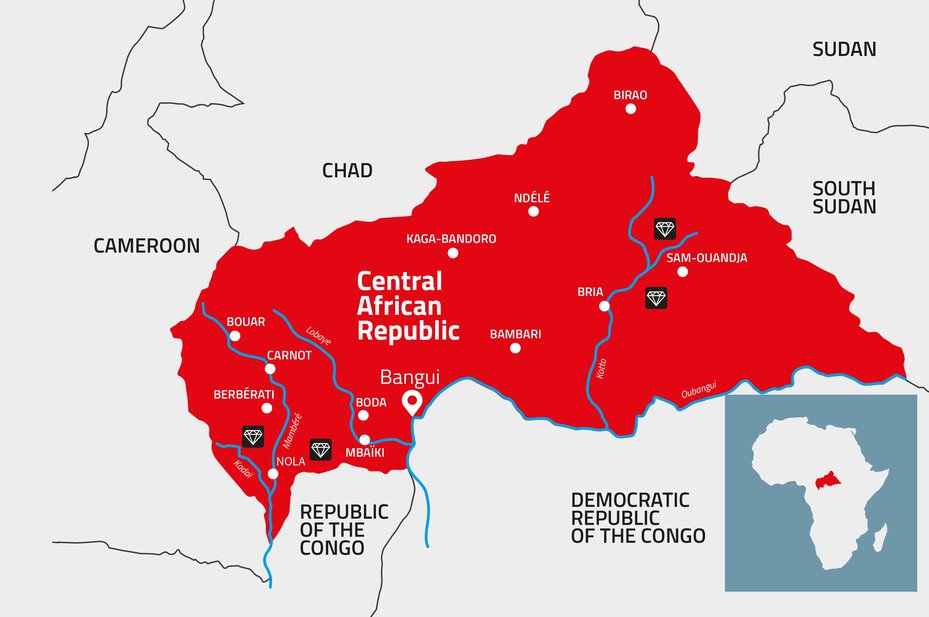

Map of the Central African Republic.Designed for Global Witness

In March 2013 a coalition of rebel groups, bound by a shared sense of political and economic marginalisation and known as the ‘Seleka’, seized CAR’s capital, Bangui. Meaning ‘alliance’ in the national language Sango, the ‘Seleka’ violently ousted then-President François Bozizé and installed their leader, Michel Djotodia, in his place. His brief rule was to be characterised by widespread abuses against the civilian population, including killings, pillage, rape and forced displacement.(10)

CAR was no stranger to coups and instability. Even prior to the fall of Bozizé—himself the victor of a coup— nearly 60 per cent of the country’s territory was beyond effective government control.(11) The descent into all out conflict was swift and intense.

The abuses, perpetrated by the predominantly Muslim Seleka, spurred a vicious backlash from loosely organised Christian and Animist self-defence groups known locally as the “anti-balaka,” or “anti-machete” in Sango. Opposed to Seleka rule, these anti-balaka militias carried out large-scale reprisals against mainly Muslim civilians, giving the conflict a sectarian dimension.(12)

The protracted period of serious violence eventually led to international pressure and the arrival of French troops, forcing Michel Djotodia to relinquish power in January 2014. As soon as he left office, Seleka forces withdrew to the northeast of the country—their traditional power base— and anti-balaka militias took control of many of the areas they left behind.

A UN peacekeeping mission (MINUSCA) was deployed in September 2014 to protect civilians and support CAR’s transition out of conflict. Presidential elections, repeatedly postponed by violence and instability, eventually took place, paving the way for President Faustin-Archange Touadéra to take the reins of a new government in March 2016.

But the conflict has not so much ended as stalled.

The Seleka have fractured following their retreat to the east, but still hold territory while visiting regular violence on the rest of the country. “Incidents have grown more severe and widespread during the months of September and October 2016,” warned the UN Panel of Experts on CAR in December 2016.(13) In May 2017 the Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect warned that "populations in the Central African Republic remain at risk of mass atrocity crimes committed by ex-Séléka rebel factions, "anti-balaka" militias and other armed groups."(14)

In Bangui, parts of a fragile government stands accused of serious corruption as it struggles to govern remaining territories alongside strongmen and remnants of the anti-balaka in the west. (15) Transparency International currently ranks CAR 159 out of 176 countries on its Corruption Perception Index. (16)

This most recent conflict has many causes. But its fortunes cannot be separated from the fate of CAR’s natural resources.

While the international community—including the Kimberley Process—are working with CAR’s government and diamond companies to establish legitimate supply chains; smugglers and traders are thriving in the parallel black market. Through these illicit channels, the violent armed groups that still control large diamond-rich areas in the east, and the strongmen that retain influence in parts of the west, may still be profiting from diamonds that reach international markets with ease.

The profits of this trade not only provide armed groups with the means they need to keep fighting, they offer an economic incentive to perpetuate chaos and instability over peace.

The official stamp of 'General' Nama

The 'General'

Like many of the Seleka’s recruits, ‘General’ Nama knew the diamond business well. A young Seleka commander, born in 1982, he grew up in one of CAR’s diamond areas near Birao in the northeast of CAR—a Seleka stronghold in recent years.

Power in CAR has always been treated as a licence to loot.(17) The Seleka appear to have been intent on continuing this legacy when their time to rule had come.

As Seleka forces seized power in 2013, ‘General’ Nama was put in charge of a prefecture in the south-west, where lucrative mineral deposits are found. But rather than stationing himself in the regional military base, Nama chose instead to take one of the main diamond buying offices in the local capital of Nola as his base. Formerly run by a local Lebanese trader, this was to become his personal bureau d'achat, or buying house.(18)

From here—using methods replicated everywhere under Seleka rule—Nama set about profiting from the resources of the area through a highly lucrative combination of business and violent coercion. Two witnesses described separate incidents in which he paid producers only a small fraction of the value of diamonds worth thousands of dollars. Sellers complained that they were powerless to negotiate in the face of potential violence.(19)

But the young General’s methods also went beyond simple coercion. Like many local Seleka commanders, Nama soon started making money by issuing ‘permits’ to those who wished to mine for diamonds and gold in the areas he controlled near the Yobe and Sangha rivers. These were granted in exchange for payments in the region of 150,000 CFA francs (around US$240) per week, reportedly for “security services.”(20) Such parallel systems of taxation and licencing formed a key part of the Seleka’s systematic exploitation of CAR’s resource wealth.

Systematic Looting

Among CAR’s most valuable natural resources are rich deposits of alluvial diamonds. In 2010, the United States Geological Survey estimated there to be 39 million carats of alluvial diamonds still left to be mined in CAR.(21) These reserves have been known and mined since at least 1929, and are concentrated in two main river systems. One is in the southwest, around the Mambere and Lobaye rivers. The other is in the eastern part of the country, around the Kotto River.

At first, the Seleka appear to have relied on extortion and looting, including during their rapid advance on Bangui in 2013.

They took everything from our hands with the force of their weapons,

recounted an owner of mines in the west of the country upon the arrival of Seleka forces. He also claims Seleka soldiers tortured his sister to extract information on where to find people with diamonds and money.(22)

Over time, however, the Seleka’s methods grew more sophisticated. Once in control of the country’s richest diamond regions, they established a parallel administration system to monitor and exploit the mining sector. Through this structure they issued mining authorisations, collected illegal taxes, and ran protection rackets that targeted miners and those operating around mining sites.

Christian traders were forced to pay up to 65 per cent of their revenue in tax and protection payments, according to one businessman in the western town of Berberati.(23)

A document signed by Nourredine Adam—the powerful head of Seleka’s intelligence operations—asks then-President Djotodia to impose a fixed tax on miners so as to increase their profits from the diamond trade. This added stream of revenue was needed, he urged, to secure more weapons and strengthen their intelligence services.(24)

Some senior Seleka commanders were also directly involved in the diamond trade. Like the young General Nama, Oumar Younous—also referred to as Oumar ‘Sodiam’—had a background in the diamond industry.(25)

With the Seleka in power, his powers and access in the sector appear to have been almost unlimited. One letter, signed by then-President Djotodia, orders that Omar ‘Sodiam’ be given full access to diamond mines in CAR as well as the authority to sell diamonds in Sudan, Dubai, Qatar and China, without any interference from the Bureau d’Évaluation et de Contrôle de Diamant et d’Or (BECDOR), the state institution formally charged with regulating the diamond and gold trades.(26)

Soon enough, the Seleka even sought to profit from CAR’s minerals by selling mining rights and concessions.

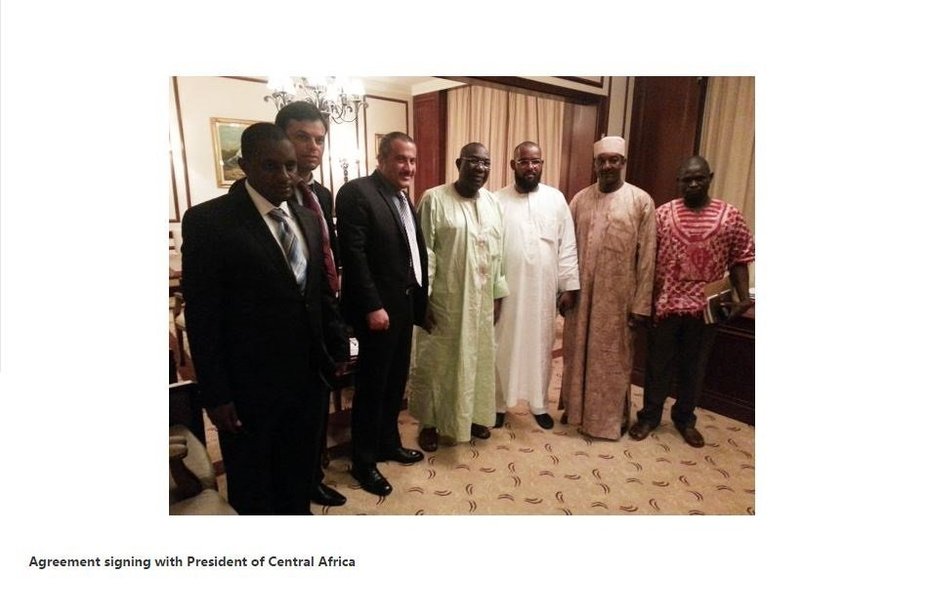

Clima Dubai representatives with CAR's then-President Djotodia (center), pictured on the company's website.

By marketing the rights to exploration and future production, the Seleka regime could push their profits well beyond those available from the relatively unsophisticated mining operations taking place across CAR. Despite the violence with which they seized power, and widespread reports of insecurity and corruption, the Seleka leadership appear to have found willing buyers for these concessions, including among international companies.

United Arab Emirates (UAE) based Clima Dubai had owned a three year, 500km2, gold and diamond mining concession in the region of Salo since the end of 2012.(27) Just weeks after Seleka fighters violently took control in March 2013, company representatives from Clima Dubai started negotiations with the rebel government in an effort to secure its future operations in the country.(28)

Another document details how the Sudanese company, Omdurman (RIDA), was issued a concession that covers an area of 1,850 km2 near Sam Ouandja for a period of three years, in return for a stated payment of 500,000 CFA francs (roughly US$815) per km2/year.(29) Global Witness has not been able to verify whether this payment was made, or whether Omdurman (RIDA) was ever active in CAR.

Neither company responded to Global Witness’ request for comment.

These are not isolated incidents. The International Peace Information Service (IPIS) have reported that as many as 34 such decrees were issued outside of normal procedures during Seleka rule.(30)

Since the Seleka’s withdrawal to the northeast in January 2014, access to this part of the country has been limited. There is nonetheless clear evidence that diamond exploitation has continued in eastern parts of the country.

In March 2015, the head of the MINUSCA office in Bria told(31) a visiting delegation from the Security Council that

diamond mining, the main economic activity in the prefect[ure], is controlled by ex-Séléka and foreign communities.

Satellite images commissioned by the Kimberley Process in late 2014 also show that diamond mining had continued near Sam-Ouandja, a town in the northeast of the country.(32)

As early as 2014 Seleka factions had also put in place illegal taxation systems, including on diamond miners, collectors, and aircraft landing in the region.(33) One document, co-signed by the then-Secretary General and the Coordinator of the Seleka and shown to Global Witness, decrees taxes of around US$800 on diamond and gold collectors operating in the area of Bria, as well as taxes on local buying offices of around US$3,000.(34)

In their December 2016 report, the UN Panel of Experts on CAR warn this trend has persisted. Ex-Seleka members are reported as present near mining zones surrounding the town of Bria in what the Panel describes as “militarized” sites.(35) One group of former-Seleka has reportedly “set up a parallel administration regulating and taxing mine activities” in Aigbando, a town 60km north-east of Bria. Smuggling is also described as rampant.(36) Diamonds from Bria are “likely to pass through Bangui, but another part is alleged to be trafficked by land to the Democratic Republic of Congo [DRC].”(37)

Though less systematic than the Seleka, anti-balaka militias also quickly adopted similar predatory behaviour after taking over areas vacated by the Seleka. In October 2014 the UN Panel of Experts reported that “members of groups associated with the anti-balaka movement are involved in artisanal diamond production (…) in the west.”(38) In 2015, they again reported(39) that

armed groups are present at several diamond mining sites in western Central African Republic, some of which are both inside and outside the proposed [Kimberley Process] green zone.

In 2014 anti-balaka groups reportedly charged traders around Berberati 5,000 CFA francs, or around US$8.(40) In the same year, a Kimberley Process official in Cameroon told Global Witness that anti-balaka members were selling CAR diamonds over the border in Cameroon.(41) This was corroborated by a CAR government agency official.(42)

In addition, some anti-balaka commanders appear to have entered the diamond trade themselves.(43) In 2016 the UN Panel of Experts reported on one individual who had been permitted to renew their artisanal mining license while allegedly remaining in command of anti-balaka forces in the Amada Gaza sub-prefecture.(44)

With one eye on CAR’s diamonds and another on a thriving conflict economy, the international community had to act.

A photo of a parcel of diamonds shared through social media

In May 2013, several months after the Seleka seized power, CAR was suspended from the Kimberley Process, the international system set up to limit the funding available to armed groups from the diamond trade. While suspended, CAR could not export its diamonds.

This export ban was meant to limit the ability of armed groups to finance their activities through diamond sales. But while this suspension has had some impact on the diamond trade in CAR, it was also routinely frustrated. A thriving black market kept diamonds flowing into neighbouring countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon.(45)

At the same time, domestic buying houses kept the domestic diamond market alive by buying stones—including from areas under the control of armed groups—and stockpiling them while they waited for the export ban to be lifted.

In the summer of 2016 their patience was rewarded. Noting the thousands of livelihoods—and government tax-revenues—which rely on CAR’s diamond trade, officials and companies had long been pushing for the suspension to be lifted.(46) Faced with former-Seleka’s continued presence in the east, however, a complete lifting of the suspension was out of the question.

In response, the Kimberley Process sought to carefully thread this needle by proposing a novel solution. A partial lifting of the blanket suspension that now permits exports only from certain parts of the country—‘compliant zones’—while, at least in theory, remaining in force elsewhere in the country.(47)

More flexible and nuanced than a complete ban, this approach aims to restart the official diamond trade in the western parts of the country edging towards stability, while simultaneously preserving the export ban in the centre and east, where diamonds proceeds are likely to fall into the wrong hands. To date, compliant zones have been identified in Berberati, Nola, Carnot, and some of Boda’s sub-prefectures.(48)

Although innovative, this partial ban carries significant risks. If it is not effectively enforced and rigorously monitored, the revived trade in CAR’s diamonds will reduce vigilance to the benefit of licit and illicit traders alike. If CAR’s diamonds offer a means of funding CAR’s peacebuilding, they also offer a lifeline to those intent on frustrating it.

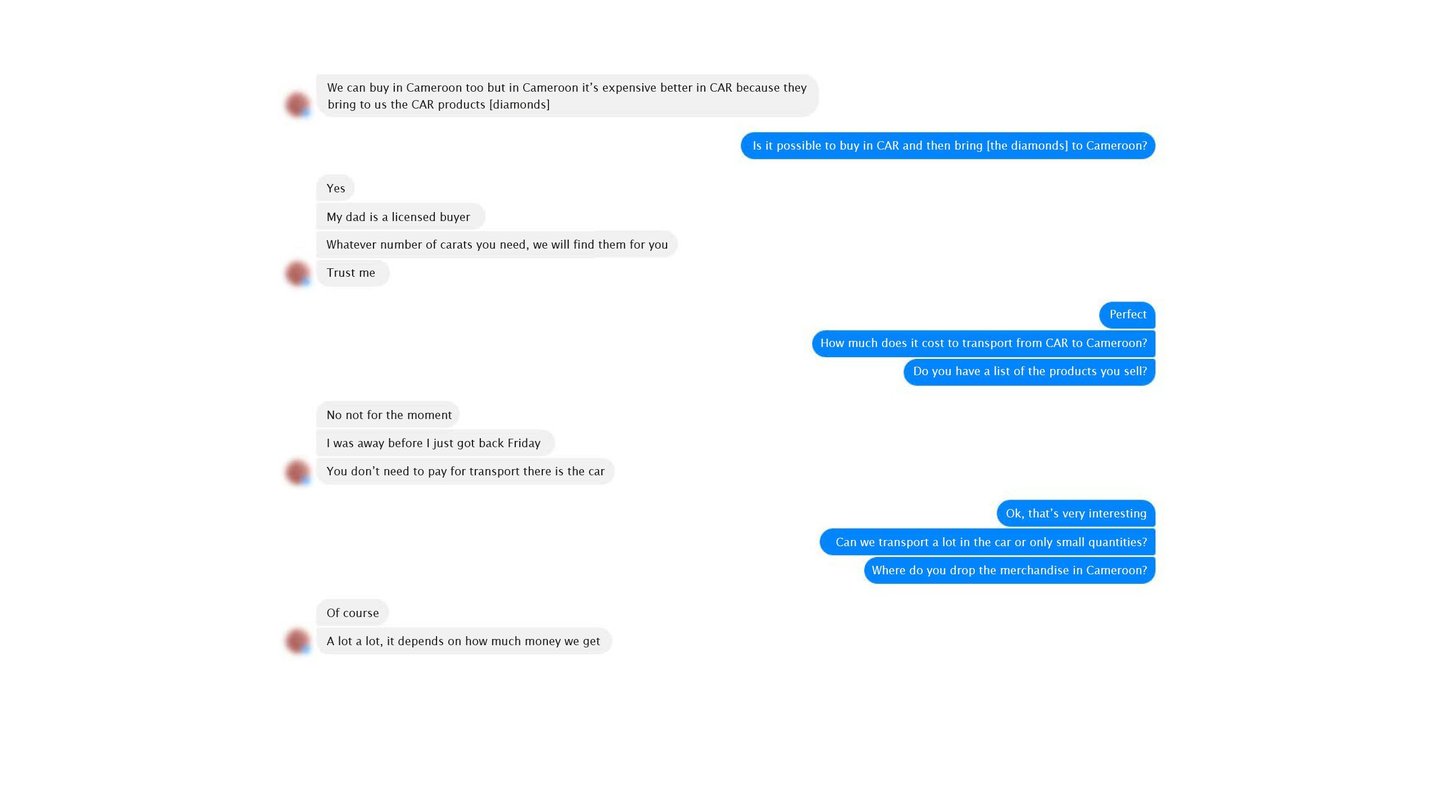

A conversation about smuggling

A conversation

Transcript of a Messenger conversation with a diamond dealer, translated from the original French

Smuggling

The Smugglers

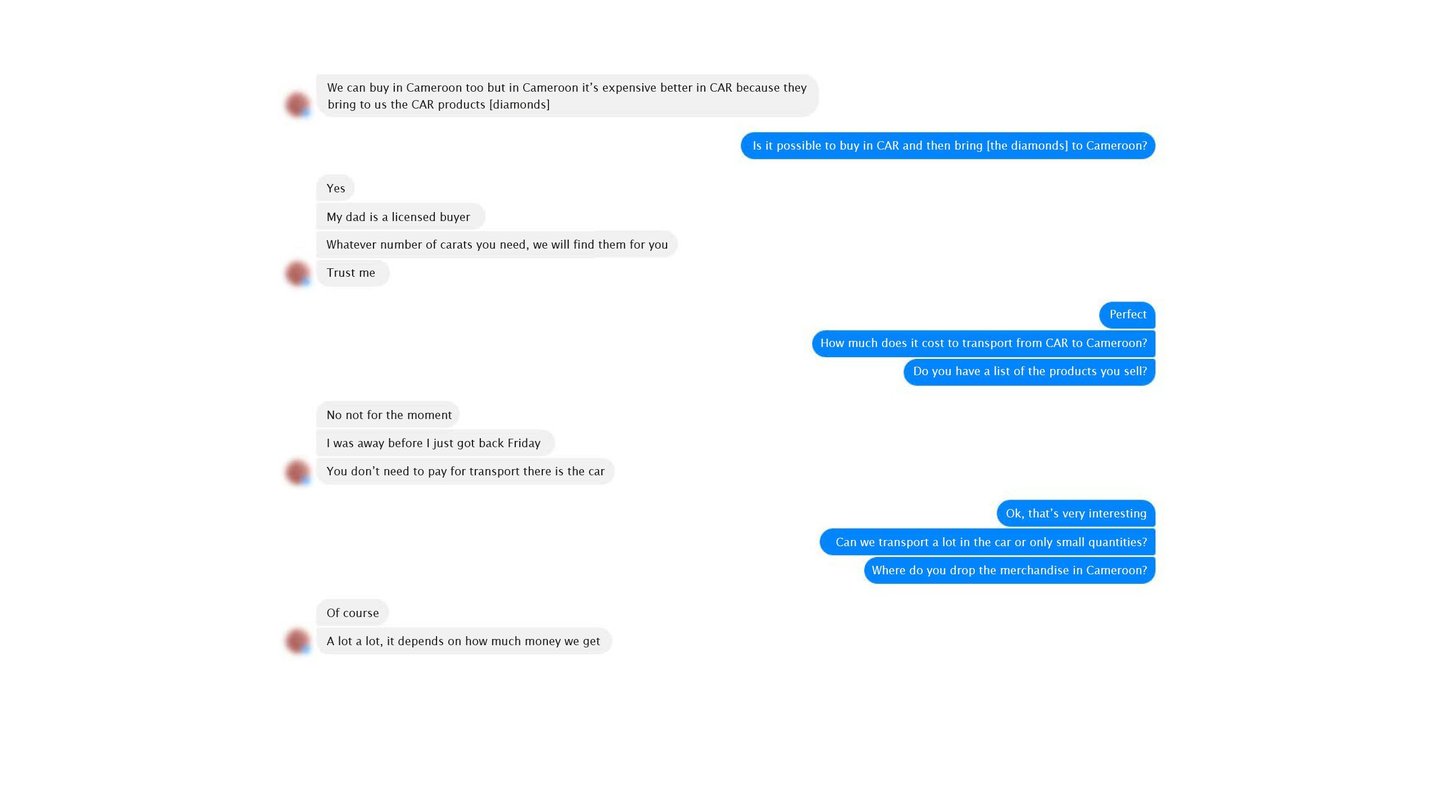

Next to a Facebook photo of a pile of rough diamonds, posted during CAR’s suspension from the Kimberley Process, a young trader, originally from CAR, but now in Brazil, leaves a telling comment.(49)

They sent us far from our home-country. Now, we can choose a new name for our diamond and change its nationality.

In the diamond world, appearances can be deceptive.

Diamonds are famously easy to smuggle. The high value of small stones means resources worth thousands of dollars can be carried and concealed with ease. Traders described the use of everything from private planes to cars and motorcycles as they discussed their experience of trafficking diamonds across CAR’s porous borders. But getting the stones out of CAR is only the first step. Before they can be sold onto international markets, the orphaned stones need a new home.

Several traders referred to this as the process of ‘naturalising’ their diamonds. Once out of CAR, buyers claim that the stones have been mined elsewhere. They mix them with other stones, get the right papers, and send them on their way—the troubled past of the CAR stowaways long forgotten.

Among the traders we speak to it is an open secret. It is hardly a secret at all. In Cameroon, we are told, we “naturalise the merchandise. They give [CAR diamonds] Cameroonian nationality.”(50) “The majority of the diamonds in Cameroon arrive thanks to us—CAR diamonds dealers. We finance the extraction in CAR and then we cross the border with them into Cameroon or export to Congo.”

The process is described in simple terms. “To ensure that diamonds are not suspicious, they do their official paperwork and they pay their little export tax in Cameroon.”(51) It all comes down to having the right connections. “I have a friend. He can do all the documents,” promises another trader.(52) Once this process is completed, CAR diamonds can be traded onward as though they were found or bought in Cameroon.

Facebook comments posted by a dealer based in Cameroon

Conversation with a CAR diamond dealer claiming to be based in Cameroon, translated from the original French with voice actors.

When you set up everything, nothing bad happens.

The Middlemen

Sader (not his real name) is a diamond dealer based in Lebanon. Over a WhatsApp call he describes an international smuggling network that he claims moves diamonds from CAR to trading centres across the world. “It is (…) business”, he tells us.(53) “With or without Kimberley, we carry the products to wherever we want.”(54)

Sader has contacts many places diamonds are mined or traded. These make up the supply chain he uses to move diamonds from CAR and into international markets. He tells us he owns a buying house in Sierra Leone along with an Italian partner.(55) He claims to have ties with diamond companies in Antwerp.(56) “You know (...), we build a sort of family of work, a collective. Some people are in mines, others are in Europe, some in offices. All of them belong to a chain we are working with.”

He uses at least two trusted couriers to carry the stones. “They are serious,” he assures us.(57) “We already have done a lot of transactions.”

When you set up everything, nothing bad happens.

This model is not unique. In April 2015 the Indian trader Chetan Balar was arrested, along with his partner, by Cameroonian authorities. They were carrying 160 carats of diamonds believed to be from across the border in CAR.(58) Chetan Balar’s Facebook profile also includes photos taken in Bangui in 2014.(59) He told us he continued to work with companies in CAR that have the documents enabling them to export, and discussed plans to return to CAR in March of this year.(60)

We spoke to a total of seven diamonds dealers, including five CAR nationals.

Five openly discussed smuggling across international borders. These smuggled diamonds were allegedly destined for buyers from Belgium, Brazil, France, China, Israel, Lebanon, South Africa, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. The largest parcel described was over 900 carats. Only two diamond dealers, both CAR nationals, stated that they did not engage in smuggling and respected the Kimberley Process in its entirety.

In May 2014 Belgian federal authorities seized three parcels of rough diamonds, totalling 6,634 carats.(61) The three parcels had been shipped through the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with Kimberley Process certificates. Even though the country of origin of the merchandise was listed as DRC, the UN Panel of Experts “believes that diamonds illegally traded from Bria and Sam-Ouandja, areas under former Séléka control, by or on behalf of Badica, have ended up in the shipments seized in Antwerp.”(62) Few other large seizures have been reported, suggesting most of diamonds smuggled out of the country are finding a relatively easy route into international markets.

In addition to Cameroon and DRC, individuals close to, or part of, the former Seleka, also confirmed smuggling links with Sudan, Chad, Qatar and Dubai.(63) One claimed that during Seleka rule he often saw planes landing directly in Sam Ouandja and Bria, coming from Sudan and other locations in CAR, to pick up diamonds.(64) Another claimed that Nourredine Adam and Oumar Younous would travel frequently to the Middle East via Sudan to sell diamonds to their contacts in Qatar and Dubai.(65)

Conversation with Sader, a Lebanese middleman. Translated from the original French with the voice of an actor.

The social network

The Social Network

Many of CAR’s diamond traders are young, ambitious, and mobile. Like their peers the world over, they have left their mark on social media. By carefully following the photos and comments through which they chronicle their business and seek new trading partners, we were able to piece together parts of the social media universe they inhabit.

Stockpiles

CAR’s international borders are porous; its internal borders even more so.

Where there is war, everything is possible

In theory, diamonds from outside CAR’s four compliant zones should not find their way into the newly created and legal supply chains that service them. Buying houses must have a local presence in a compliant zone and provide a paper trail that follows the diamonds from mine to export. A monitoring team checks parcels proposed for export using forensic techniques that should allow them to tell diamonds mined in the west from diamonds mined in the east.

But, as one trader puts it, CAR “is a country where there is a war, and where there is war”, we are reminded, “everything is possible.”(66)

The UN Panel of Experts have warned that diamonds from CAR’s compliant zones may be linked armed groups, as well as human right abuses. These include serious constraints on the freedom of movement of returning Muslim traders in western CAR.(67)

While only a few parcels have been exported to date through the resumed Kimberley Process channels, some local and international traders clearly see it as an opportunity. Some professed indifference to the boundaries of the compliant zones. One of them told us that “you can buy [diamonds] in Bria [in eastern CAR], that you bring to Bangui and then you export.”(68) Others appeared to believe the ban had been lifted for the entire country. “Now the embargo is lifted. The country is pacified,” one dealer tried to explain.(69)

Just as CAR’s diamonds continue to flow into neighbouring countries, there is a risk of new internal smuggling channels undermining the Kimberley Process’ efforts as stones are carried into the compliant zones from elsewhere in the country. Diamonds from non-compliant parts of the west appear particularly at risk of slipping into compliant zones through indifferent or opportunistic traders. These are unlikely to be detected by any of the secondary forensic tests currently in place to exclude eastern stones that may have slipped through the net.

In addition to freshly mined stones from outside the compliant zones, another threat to the integrity of the new system stems from the legacy of CAR’s conflict and suspension.

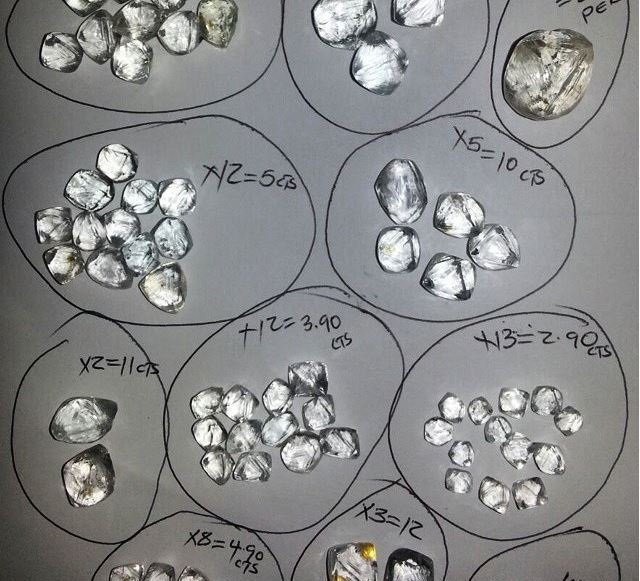

Diamonds pictured on a dealer's Facebook page

Somewhere in Bangui tens of thousands of carats of diamonds are waiting.

A photo shared by a diamond trader on his social media account

CAR’s suspension from the Kimberley Process banned the export of diamonds, not their purchase. Several of CAR’s large buying houses kept buying diamonds during the period of CAR’s suspension, amassing considerable stockpiles. Diamonds were purchased from across the country, including in areas controlled by armed groups, undermining the effectiveness of the ban. At worst, what was intended to stem the flow of conflict diamonds became a mere cash-flow challenge for well-resourced buying houses.

Badica (Bureau d’Achat de Diamants en Centrafique) was one of the buying houses that kept buying. By July 2014, the UN Panel of Experts reported that Badica had purchased 2,896 carats of diamonds. Most from Bria and Sam-Ouandja, where Seleka forces were consistently present.(70) The Panel concluded that “Badica’s legal and illegal purchases from those areas provided sustainable financial support for the former Séléka, in violation of the United Nations sanctions regime.”(71)

Another member of this group is Badica’s sister company in Antwerp, Kardiam.(72) On 20 August 2015, both Badica and Kardiam were placed on the UN sanctions list following the seizure of suspected CAR diamonds destined for Kardiam in Antwerp.(73)

Badica have denied all these allegations, both to Global Witness and to the Panel of Experts. Kardiam declined to meet researchers from Global Witness, and have not responded to a request for comment.

Sodiam (Société Centraficaine du Diamant) is one of the largest buying houses in CAR. Sodiam also kept buying diamonds during the period of CAR’s suspension. The company confirmed to Global Witness that it is purchasing around 30,000 carats per year, principally from the west of CAR.(74) Information in a third party audit, available from the company’s website, is consistent with this estimate.

In June 2015 solicitors representing Sodiam told Global Witness that Sodiam’s purchases were “concentrated in the west of the CAR,” adding that “the east has been designed a ‘red zone’ and therefore off limits by the Government of the CAR due to the fact that it is controlled by Seleka forces.”(75)

In December 2015 the Panel reported that Sodiam’s stocks had reached 70,845 carats as of 5 September 2015.(76) According to Sodiam’s own internal audit, these stocks included roughly 6,400 carats of diamonds purchased in the east of the country, between May 2013 and July 2015.(77) A source confirmed to Global Witness that Sodiam bought diamonds from Berberati, Yaloke and Bria during the period of Seleka rule.(78)

In 2014 the UN Panel of Experts spoke to several diamond collectors in the west of CAR. These collectors told the UN Panel that they could not assure their customers that their diamonds had not financed armed groups, given the significant presence of anti-balaka groups in and around diamond mines. Several of these dealers stated that they had sold diamonds to Sodiam. The Panel therefore concluded that it “believes that Sodiam’s purchases have incidentally financed anti-balaka members.”(79)

The Panel did, however, make it clear that it believes Sodiam have taken positive steps to mitigate against this risk, and that Sodiam does aim to exclude purchases from military personnel and members of armed groups.

Sodiam has denied these allegations in communication with Global Witness. Representatives of the company have also contested the findings reported by the UN Panel of Experts, and have stated that Sodiam has never “purchased anything that could reasonably be described as a conflict diamond.”(80)

Sodiam also insists that it conducted “due diligence” on all its diamond purchases in CAR. Representatives of Sodiam referred Global Witness to a document titled “Sodiam Procedures Manual,” placed on its website, which contains the companies due diligence procedures.(81)

Both the website and the 800 word document in question appear to have been created in June 2015, shortly after Global Witness contacted Sodiam with a request for information about its due diligence practices.

Sodiam was one of the loudest voices calling for CAR’s Kimberley Process suspension to be lifted. In a letter dated 28 May 2015 the transitional government’s Minister of Mines and Geology thanks Sodiam for its assistance during the Kimberley Process review mission of May 2015. The letter then expresses the wish that the company’s “patience” will be “rewarded” once the suspension is lifted.(82)

If buying houses are permitted to export all, or most, of their stockpiled diamonds, their patience will certainly have been rewarded.

The Kimberley Process has recently proposed a forensic audit in an effort to differentiate stocks amassed in the east from those purchased in the west.(83) This suggests officials may be considering allowing portions of the stockpiles to be exported as part of the restored Kimberley Process. This would most likely apply to stones thought to have been mined in what are now the western compliant zones.

This would be nothing but a sleight of hand of benefit only to CAR’s buying houses.

Whether purchased in the east or in the west, the stockpiled diamonds are at serious risk of having financed armed groups. Regardless of what may now be the case in the relevant compliant zones, these stones were purchased during a period when an anti-balaka presence in and around western mines was as well-established, as was a Seleka presence in the east.

Absent detailed proof of robust due diligence conducted at the time of their purchase, no stones purchased during the period of CAR’s suspension from the Kimberley Process can appropriately be described as “conflict free.” No company should be rewarded for irresponsible sourcing during a violent conflict. This is the risk the Kimberley Process is running if it chooses to look the other way and ignore the troubled past of CAR’s stockpiles.

The game of stones

Diamonds marked #RCA [CAR] #diamond sorted by carat weight and posted on social media

For decades the international community has witnessed the fortunes of fragile states destabilised and pushed toward conflict by their own resource wealth. There are important lessons to be learnt from experiences in countries like Liberia, Sierra Leone, Angola, and Côte d’Ivoire. There are also important lessons to be learnt from CAR’s own history, which has been plagued by cycles of predatory rule and violent coups. One such lesson is the potential long-term costs of a hasty resumption of the trade in natural resources, particularly in the absence of effective control and governance of the sector.

The course on which CAR sets off now will define the next phase of its economic and political development. If its resources are again seen as fair game, even in the absence of good transparent governance, this risks further entrenching the corruption and looting that has plagued the sector in the past. CAR deserves the full support of the international community, including its companies. This is an occasion for a new start—not a business opportunity.

Recommendations

To the authorities of the Central African Republic

Prioritise extending effective government control to all of CAR’s territory, with special attention paid to mineral rich regions, key transportation routes, and border crossings. This should be complemented by a commitment to re-establishing local governance legitimacy which is earned by tackling corruption and promoting transparency.

Work with Kimberley Process officials to develop strong traceability systems to ensure the integrity of any resumed export trade, and publish all data provided to the Kimberley Process Monitoring Team, as well as details of all production, exports, and revenue collected by the government.

Confiscate all diamond stocks amassed by buying houses during CAR’s suspension from the Kimberley Process, unless the companies can offer evidence—such as robust due diligence procedures and reporting—that the diamonds have not directly or indirectly funded armed groups in any part of the country at the time they were purchased. Proceeds from the sale of seized stocks should be announced publicly and managed transparently, with the full proceeds going to the public interest, including the victims of CAR’s ongoing conflict. Any company that purchases diamonds from seized stocks should report publicly and fully on this process, including any risks identified and mitigated, in line with the Organisations for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains.

The Special Criminal Court should investigate key actors, including companies, suspected of having committed the war crime of pillage. Article 6 of CAR’s 2009 Mining Code makes it clear that CAR’s natural resources are the property of the state. Throughout the conflict, evidence suggests that armed groups and individuals have appropriated and profited from these resources, and have done so in the context of an armed conflict and without the consent of a legitimate government.

Support efforts to promote the responsible sourcing of diamonds, gold, and other minerals from CAR by facilitating the implementation of international due diligence frameworks, as recommended in other mineral-rich conflict affected areas, and as encouraged by key international multi-stakeholder initiatives, including the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the OECD's Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains.

To the United Nations, UN-mandated bodies, the International Contact Group on the Central African Republic, Donor governments and institutions

Support local civil society organisations in order to promote effective long-term oversight and monitoring of CAR’s extraction and trade of natural resources, and broad participation in the reform process—including processes linked to resuming diamond exports.

Existing sanctions regimes should be fully implemented and expanded to cover other individuals and companies shown to be driving the conflict economy. This may include other key political figures and, where sufficient evidence is available, the UN Sanctions Committee should also consider further companies and economic entities, whether based in CAR or internationally, as appropriate targets for sanctions.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) should support the investigations and prosecutions of CAR’s newly established Special Criminal Court, including investigations into the crime of pillage. Where necessary, the ICC should seek accountability for crimes committed in CAR that fall within its jurisdiction, including the war crime of pillage.

To the Kimberley Process, the Follow Up Committee, and the tripartite Kimberley Process Monitoring Team

Compliant zones must be carefully defined, and regularly monitored. A compliant zone is described as one with “sufficient CAR government control” and no “systematic rebel-based or armed-group” activity. These terms must be drawn narrowly and regularly monitored to ensure their credibility. No area should be designated as a “Compliant Zone” under the proposed Kimberley Process Operational Framework until this is the case. It is critical that such validation be done at the mine site level, rather than at the level of prefectures or equivalent sub-national administrative units. Attention should also be paid to the full range of means by which armed groups can profit from the trade, both directly and indirectly. Statistical monitoring of the trade will not alone provide sufficient assurances that conflict diamonds are being kept out of any legitimate supply chains.

Local civil society representatives should be included at every stage of the process, as provided for in the Operational Framework, and given a strong voice.

Diamonds stockpiled by companies, without proof of robust due diligence, should not be permitted to enter at any point along the restored supply chain. This is of special concern as the Operational Framework does not discourage companies from purchasing and stockpiling diamonds from outside the compliant zones. The framework only requires companies to “segregate” these purchases from those made in compliant zones, and to submit their stocks to inspection. Any seized stocks that are sold should be accompanied by a clear and transparent statement of their history.

Neighbouring countries, and trading centres, must increase their vigilance, and bolster border security, in an effort to limit the smuggling of diamonds from the CAR, particularly in the Kimberley Process member states, the DRC, Cameroon, UAE, and Antwerp, as well as in Chad and Sudan.

Any company that participates in the resumed trade must also, as a prerequisite, commit to conducting and reporting on their risk-based supply chain due diligence in line with the OECD’s standard.

Any resumption of the diamond trade must make sure it does not inadvertently reward violence or entrench segregation and displacement. The conflict in CAR has had a serious impact on the demography of CAR, displacing one in five—including up to 80 per cent of the Muslim population. There is a serious risk that the creation of a diamond supply chain in these parts of the country will amount to a tacit endorsement of this forced displacement, and further entrench this segregation in a way that impedes the return of the displaced population. It may also inadvertently reward those who stand to profit from the resumed trade for any role they might have played in the violence that led to the displacement. Any resumption of the diamond trade should do its utmost to avoid such consequences. As a starting point, any proposal should be accompanied by a careful study of the impact the conflict has had on the relevant sector of the diamond trade, with a particular focus on “compliant zones.”

To the diamond industry

Companies sourcing minerals directly or indirectly from CAR, including gold and diamonds, should undertake and publicly report on their risk-based supply chain due diligence. The Kimberley Process is not sufficient to curb the illicit flow of CAR diamonds. Its limitations indicate the need for a complementary process that engages companies in the diamond supply chain and encourages them to address the human rights risks and impacts associated with their operations. Companies sourcing mineral resources from CAR should be undertaking due diligence on their supply chains to OECD standards and publicly reporting on their efforts to do so. Any company participating in resumed trade from compliant zones should, as a precondition, be required to conduct due diligence to the OECD standard.

References

1

Global Witness voice call, July 2016

2

Global Witness voice call, July 2016

3

Global Witness created a social media profile for a fictitious diamond buyer that claimed to be based in Antwerp, but operate internationally.

4

Global Witness voice call, July 2016

5

Global Witness interview, Cameroon, 2014

6

Global Witness voice call, January 2017

7

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Central African Republic, http://www.unocha.org/car (last accessed June 2017)

8

UNDP, The Human Development Index 2015, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/ranking.pdf (data is for the year 2014)

9

International Food Policy Research Institute, Global Hunger Index 2016, http://ghi.ifpri.org/

10

See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Central African Republic: Materials published by Human Rights Watch since the March 2013 Seleka Coup, March 2014, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/car0314compendium_web.pdf

11

Didier Niewiadowski, "La République centrafricaine: le naufrage d’un Etat, l’agonie d’une Nation", Revue d’étude et de recherche sur le droit et l’administration dans les pays d’Afrique, May 2014, p. 10, http://afrilex.u-bordeaux4.fr/sites/afrilex/IMG/pdf/La_Republique_centrafricaine.pdf

12

See, for example, Human Rights Watch, Central African Republic: Materials published by Human Rights Watch since the March 2013 Seleka Coup, March 2014, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/related_material/car0314compendium_web.pdf

13

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 5 December 2016, p. 2 http://undocs.org/en/S/2016/1032

14

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, Central African Republic, http://www.globalr2p.org/regions/central_african_republic (last accessed June 2017)

15

See, for example, Christopher Day & Enough Project team, The Bangui Carousel: How the recycling of political elites reinforces instability and violence in the Central African Republic, August 2016, https://enoughproject.org/reports/bangui-carousel-how-recycling-political-elites-reinforces-instability-and-violence-central-a

16

Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2016, http://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016#table

17

See, for example, the Final Report of the UN International Commission of Inquiry on the Central African Republic, 22 December 2014, p. 14 (para.25), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/928

18

Global Witness interviews, Central African Republic, 2014

19

Global Witness interviews, Central African Republic, 2014

20

Document on file with Global Witness

21

US Geological Survey, Alluvial Diamond Resource Potential and Production Capacity Assessment of the Central African Republic, Scientific Investigations Report 5043, 2010, p. 1, http://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2010/5043/pdf/sir2010-5043.pdf

22

Global Witness interview, Central African Republic, 2014

23

Global Witness interview, Central African Republic, 2014

24

Document on file with Global Witness

25

The Central African Republic Sanctions Committee, Oumar Younous, 20 August 2015, https://www.un.org/sc/suborg/en/sanctions/2127/materials/summaries/individual/oumar-younous See also: Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 1 July 2014, p.18 (para. 67), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/452

26

Document on file with Global Witness

27

Document on file with Global Witness

28

Clima Dubai’s website includes a photograph of the company’s representatives meeting with then-President Michel Djotodia, dated 19 April 2013. A screenshot of this webpage is on record with Global Witness.

29

Document on file with Global Witness

30

IPIS, Mapping Conflict Motives: the Central African Republic, November 2014, p.36, http://ipisresearch.be/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/IPIS-CAR-Conflict-Mapping-November-2014.pdf

31

What’s in Blue, “Dispatches from the Field: Council Delegation Visits the Central African Republic”, 11 March 2015, http://www.whatsinblue.org/2015/03/dispatches-from-the-field-council-delegation-in-the-central-african-republic.php#

32

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, Annex 27, p.103, http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762

33

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, p. 32 (para. 123), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762 See also: Interim Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African, 1 July 2014, p. 14 (para. 41), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/452

34

Document on file with Global Witness

35

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 5 December 2016, p. 40 (para 171), http://undocs.org/en/S/2016/1032

36

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 5 December 2016, pp. 40-41 (para 169 and 172), http://undocs.org/en/S/2016/1032

37

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 5 December 2016, p. 42 (para. 173), http://undocs.org/en/S/2016/1032

38

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, p.3, http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762

39

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 21 December 2015, p.44, http://undocs.org/en/S/2015/936

40

RJDH Berberati, "Les multiples barrières empêchent la libre circulation dans la ville,” 9 September 2014, https://centrafricmatin.wordpress.com/2014/09/04/depeche-rjdh-radios-communautaires-206/

41

Global Witness interviews, Cameroon, 2014

42

Global Witness interview, Central African Republic, 2014

43

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, pp.33-34 (paras.129-130), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762 See also Le Monde, “La contrebande de diamants centrafricains explose”, 8 August 2014, http://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2014/08/08/la-contrebande-de-diamants-centrafricains-explose_4469128_3212.html

44

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 5 December 2016, p. 52 (para. 228), http://undocs.org/en/S/2016/1032

45

PAC, From Conflict to Illicit: Mapping the Diamond Trade from Central African Republic to Cameroon, December 2016, p. 3, http://www.pacweb.org/images/PUBLICATIONS/from-conflict-to-ilicit-eng-web%202.pdf

46

Letter dated 28 May 2015 from the transitional government’s Minister of Mines to Sodiam. Document on file with Global Witness. See also: Le Monde, “La contrebande de diamants centrafricains explose”, 8 August 2014, http://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2014/08/08/la-contrebande-de-diamants-centrafricains-explose_4469128_3212.html And see also, VOA “La RCA demande l’allègement de l’embargo sur l’exportation de son diamant,” 23 September 2014, http://www.voaafrique.com/a/la-rca-demande-l-allegement-de-l-embargo-sur-l-exportation-de-son-diamant/2459209.html

47

Kimberley Process, Annex: Operational Framework for Resumption of Exports of Rough Diamonds from the Central African Republic, https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/246604.pdf

48

Kimberley Process and UAE Ministry of Economy, Kimberley Process Declares Three More Zones In Central African Republic (CAR) as ‘Compliant Zones’, 27 September 2016, http://bit.ly/2sm8ren

49

Facebook post, copy on file with Global Witness

50

Global Witness voice call, July 2016

51

Global Witness voice call, July 2016

52

Global Witness voice call, January 2017

53

Global Witness voice call, February 2017

54

Global Witness voice call, February 2017

55

Global Witness voice call, February 2017

56

Global Witness voice call, February 2017

57

Global Witness voice call, February 2017

58

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 21 December 2015, p. 48 (para 237). http://undocs.org/S/2015/936 See also Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 5 December 2016, p. 52 (para. 225), http://undocs.org/en/S/2016/1032

59

Facebook post, copy on file with Global Witness

60

Global Witness conversation via Facebook Messenger, January 2017

61

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, p.3, http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762

62

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, p.32 (para. 127), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762

63

Global Witness interviews, Central African Republic, 2014. See also letter signed by President Djotodia granting Omar ‘Sodiam’ access to diamond mines in CAR and authority to sell diamonds in Sudan, Dubai, Qatar and China without interference from BEDCOR, on file with Global Witness.

64

Global Witness interview, Central African Republic, 2014

65

Global Witness interview, Central African Republic, 2014

66

Global Witness voice call, July 2016

67

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, December 2016, p.3, http://undocs.org/en/S/2016/1032

68

Global Witness voice call, January 2017

69

Global Witness voice call, July 2016

70

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, pp.31-32 (para. 122) and Annex 25, pp. 100-101, http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762

71

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, pp.32-33 (para. 127), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762

72

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, p.30 (para. 116), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762

73

UN Press release, Security Council Committee Concerning Central African Republic Lists One Entity, Three Individuals Subject to Measures Imposed by Resolution 2196 (2015), 20 August 2015, http://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sc12018.doc.htm

74

In correspondence with Global Witness, through the company’s lawyers.

75

Document on file with Global Witness

76

Figures calculated by adding figures reported in the Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 21 December 2015, pp.28-29 and Annex 5.17 (p.295) and figures reported in the Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, p.33. In Annex 5.17 of its December 2015 report the Panel also reports a lower figure of 70,036 for Sodiam’s total stocks, but this number is inconsistent with the disaggregated figures listed in the two reports. Discrepancies may arise when records in the capital Bangui differ from those of field offices.

77

Audit dated 2 September 2015. The audit was previously available from Sodiam’s website: http://sodiam.cf, but has since been removed. Copy on file with Global Witness.

78

Global Witness interview, Central African Republic, 2014

79

Final Report of the UN Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic, 29 October 2014, p.34 (para. 131), http://undocs.org/en/S/2014/762

80

In correspondence with Global Witness, through the company’s lawyers.

81

Document available from Sodiam’s website: http://sodiam.cf/sodiam-c-a-r-company-principles-and-procedures/ (last accessed June 2017)

82

Document on file with Global Witness

83

Letter from the Kimberley Process CAR Monitoring Team to IDEX Online, 18 December 2016, document on file with Global Witness

Resource Library

Download the full report: Game of stones

Download Resource