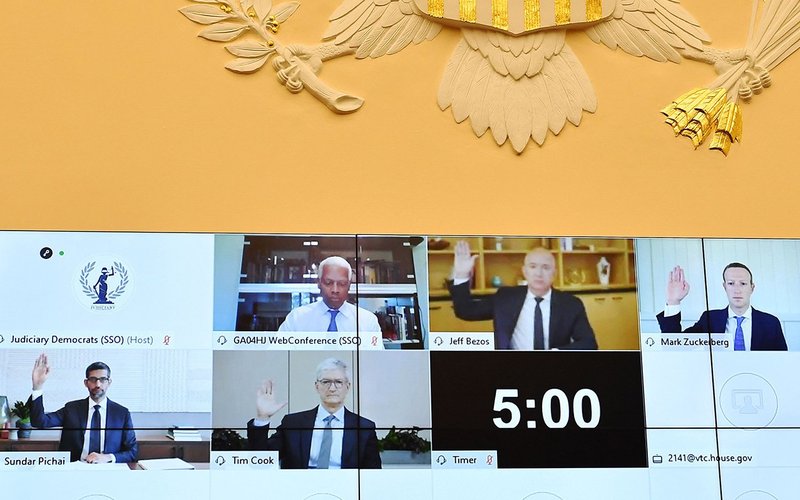

Yesterday’s US House Judiciary hearing into the dominance of the four most powerful tech companies in the world - Facebook, Google, Apple and Amazon - came at a pivotal moment. Never before have we seen such huge power of ‘Big Tech’, in terms of their reach, wealth and market dominance.

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, Google CEO Sundar Pichai, and Apple CEO Tim Cook are sworn-in before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law. Shutterstock

All four companies were represented by their CEOs at the hearing. On an individual level, living through a global pandemic, we are all increasingly reliant on their services for so many aspects of our lives, whether news, education, work, food and health information.

And yet while the power of Big Tech has grown to staggering new levels, their regulation and oversight has not. Just look at the negligible tax paid by these companies globally - the amount they have avoided is potentially as high as $100bn over the last 10 years - while public coffers go into freefall, and the level of disinformation facilitated.

The World Health Organisation recently described the false information shared on Facebook about vaccinations as “a major threat to global health that could reverse decades of progress made in tackling preventable diseases.” This is a reality regulators are starting to wake up to, both in the US and Europe.

Of course at its best, technology that allows us to connect with friends and families, to share experiences and to speak out against injustice to a mass global audience is important and powerful. When social media first attracted huge numbers of users it was seen as a “great leveller”, a tool for democratising political debate and circumnavigating repressive governments and censorship laws.

The speed at which information can spread has allowed protest networks and other resistant movements to have spectacular spillover effects. It has played an obvious role in the WikiLeaks exposés, the Arab Spring uprisings, the Occupy movement, and anti-austerity movements in Europe. Over the past decade, hashtags like #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo have blossomed into full-blown campaigns for change, as activists have shared their stories and disturbing footage of violence, discrimination and hate.

But the growth of a monopoly of Big Tech firms who control the data and information of billions of people comes at a serious cost. Such a concentration of power in the hands of such a small number of companies poses a danger to democracy - particularly when it comes to platforms like Facebook and Google, which have become new and hotly contested battlegrounds for political campaigns.

These platforms give politicians access to hugely valuable data about the voters they’re trying to reach. One of the best-known examples of this is how Cambridge Analytica claimed it was able to harvest the data of 50 million US citizens through their Facebook profiles as part of their work for the Donald Trump campaign. Although the rules around this have now been tightened up, the ability to sell information about its users is key to Facebook’s profitability.

While it’s not new that communication is fundamental to political campaigning, the tactics being used on digital platforms are still in their infancy. Campaigns now pay a lot of money for experts who can develop strategies for microtargeted ads, which design messages specifically aimed at a group of voters (segmented via the data that is bought from the platforms themselves or off-the shelf audiences from data brokers).

Trump’s digital leads credit their social media strategy with securing his Presidency in 2016. They claim, from 2014 onwards, they would be running between 40,000 to 50,000 variants of their adverts on Facebook each day, testing how they performed in different formats and with slightly different messages aimed at different voter groups. On the day of the third presidential debate in October 2016 - as the traditional media raged about the Access Hollywood tapes - Trump’s campaign was running 175,000 variations of a ‘Crooked Hillary’ message on Facebook.

So, as much as new technology offers many new positive ways for reaching voters, it also increases the risk of the process being distorted. For example, by targeting specific segments of the population to suppress their vote, spreading misleading and inflammatory statements or doctoring material via ‘deepfakes’ to undermine political opponents. And now, as the COVID pandemic changes so many aspects of our lives, some States in the US are pushing for online voting for November’s Presidential election, which raises new risks of interference. The UK’s long-awaited report into Russian interference found that despite the central role played by social media companies in elections, they “are failing to play their part” in addressing threats to democracy.

A big part of the problem is that for too long many digital companies have operated as black boxes, without meaningful scrutiny or accountability. A number of these businesses derive the majority of their profit from commodifying our data - also known as surveillance capitalism - and selling it to the highest bidder. Google and Facebook and their subsidiaries make about 83 percent and 99 percent of their respective revenue from selling ads.At yesterday’s Congressional hearing Representative Jaypal laid out data showing Google controls up to 90% of this advertising market. The complex algorithms they use are so secretive we don’t even know on what basis we are shown information and how we have been profiled.

The impact of these political digital strategies may be unclear and, while we’re not suggesting that everyone is naively persuaded by a well designed Facebook ad, the fact campaigns are willing to spend many millions of dollars investing in these platforms suggests they could have a real impact. It is time to lift the lid on online political campaigns and make it harder for political players to target us with information that could either be damaging or false - or simply conceal who is paying for the information or why it’s being seen by some groups of voters and not others. At the moment, information on political advertising - for example via Facebook’s ad libraries - is all too often incomplete, unverified and patchy, with many countries not even fully covered by the limited transparency measures that do exist leaving citizens in the dark.

Yesterday’s historing hearing closed with a robust statement by Representative Cicilline, “These companies, as they exist today, have monopoly power,” he said on his conclusions from the antitrust investigations. “This must end. Some need to be broken up, all need to be properly regulated and held accountable.”

It wasn't always this way, nor do we have to accept the current situation as one that we simply cannot change. Regulators now have a golden opportunity to recalibrate the system and ensure it protects people’s rights and our democracies. The next six months will be quite a ride - the US elections in November will likely see these tensions play out in a dramatic way, follow up from yesterday’s hearing and the EU’s proposal for a Digital Services Act expected later this year is already attracting a huge lobbying battle. Watch this space!

Read this page in