WIRED magazine today published an account of our investigations in the Malaysian state of Sarawak. Our first trip there was undercover. Equipped with pinhole cameras and hidden mics we smiled politely as the state’s ruling family explained with a disturbing sense of entitlement how they were selling off state and indigenous-owned forests to line their own pockets. It is no coincidence that Sarawak’s rainforests are some of the most endangered on earth.

Unsurprisingly, Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud and family later denied the allegations of corruption we pinned to them. What is surprising is that Taib has since emphatically denied that Sarawak’s forests are being managed unsustainably. Surprising because Sarawak – which is around the size of the UK – has one of the highest rates of tropical deforestation in the world, exporting more tropical timber than all of Africa.

To prove Chief Taib wrong we’ve substituted our spy cameras for satellites, and are gathering new evidence of the scars of Sarawak logging, the companies behind it and the markets driving it.

Before and after Samling

These ‘before’ and ‘after’ shots show the speed and scope of destruction.

Sarawak’s three-decade long timber rush under Chief Taib’s rule has given rise to some of the world’s heavyweight timber companies, the biggest of which are Samling and Shin Yang. Chameleons of their trade, both companies are refashioning themselves as palm oil companies so that they can continue to cultivate oil palms on deforested land left behind by logging.

The images above are of land awarded to Samling (timber license T/0413). This forest is home to the indigenous Penan people of Ba Jawi, who have lived from it for generations. It is also located in the Heart of Borneo, a cross-border conservation initiative that is internationally recognised for its ecological importance.

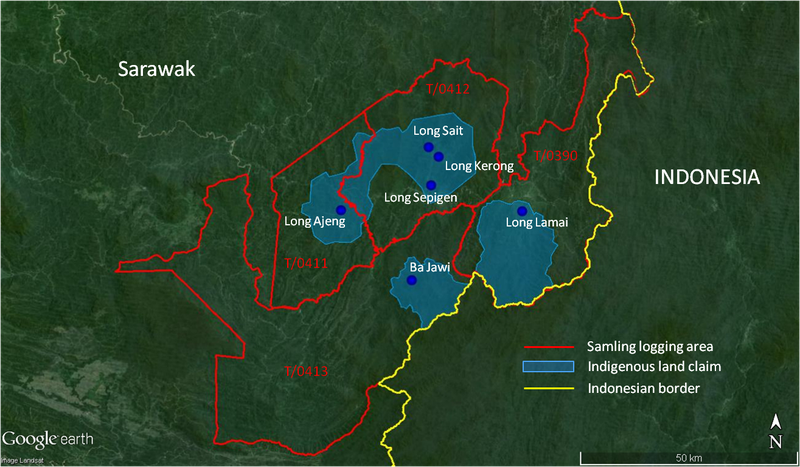

Samling is bulldozing through significant chunks of indigenous homeland, as the illustration above shows. (The red here shows the boundaries of Samling logging areas, the blue indigenous-claimed land). Indigenous rights to land should be guaranteed under Malaysian law, but the Penan communities we interviewed in Sarawak claimed their protests were being met with government intimidation or indifference.

The Heart of Borneo’s Cardiac Arrest

At a glance this looks like a craggy mountain range. In fact it’s Shin Yang territory (timber license T/3228) – also in the Heart of Borneo – captured by satellite in February 2013. Shin Yang has constructed a sprawling network of roads to access and transport its timber, cut into steep hillsides. This picture below from another Shin Yang logging area (timber license T/3342) shows the erosion and landslides that ensue.

It is not only Sarawak’s governors and loggers who are to blame for this. They can only enrich themselves from the natural kingdom they preside over for as long as global demand for timber and palm oil fuels their trade.

Japan is key here – Sarawak’s biggest timber importer for over twenty years. Unlike the US, EU and Australia, however, Japan lacks legislation that obliges importing companies to prove that forest products are produced legally. As our new briefing on Japan’s timber imports states,the assumption of innocence is inappropriate when dealing with Sarawak – the risks are too high that its timber has troubling roots. But containers full of Samling and Shin Yang timber products continue to stream into Japanese ports with few questions asked.

These satellite images offer a stark counterpoint to the path of sustainability that Sarawak claims to be on. They bring into focus rainforests on the brink of extinction and rural communities being robbed of their livelihoods and lifeline. We have caught Sarawak on camera, but we need buyers and consumers on board if we’re to preserve those last flecks of green on its map. It’s time to stop buying the produce of unchecked industrial exploitation.