In a new investigation into social media’s ability to detect election disinformation and foreign interference, TikTok and YouTube rejected a set of prohibited ads.

The results are encouraging as we approach the UK general election – but differ from the platforms’ previous failures in other parts of the world, raising questions about inequitable standards.

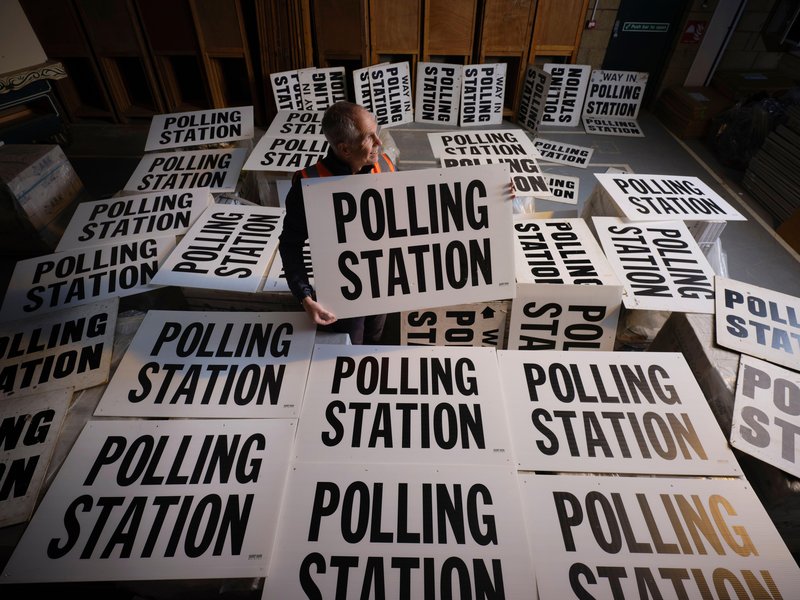

Social media has a chequered record when it comes to moderating election content. With numerous national elections still to take place in 2024, Global Witness and Democracy for Sale launched a new test of social media platforms’ preparedness for operations seeking to undermine democratic processes, this time focusing on the UK.

We chose to test YouTube and TikTok – two prominent platforms for accessing entertainment and information in Britain. In the past few weeks, Labour and the Conservatives have launched official accounts on the platform, posting content that swiftly racked up millions of views.

Social media platforms are required under the UK’s Online Safety Act to effectively mitigate and manage the risk that their services are used for foreign interference. YouTube’s ad policies prohibit the publication of election misinformation, while TikTok’s prohibit any references to an election whatsoever.

We tested both aspects by submitting a set of four ads to each platform containing election misinformation from three foreign countries – Brazil, Denmark, and Kenya – as well as from within the UK.

The ads included videos calling on viewers not to vote for parties supporting an “ongoing genocide against Russian-speaking Ukrainians” underneath photographs of Rishi Sunak, Keir Starmer and Volodymyr Zelenskyy. There is no evidence for this statement.

Another purported to be from the “UK Election Authority” (a made-up body) and threatened criminal damages against anyone attempting to vote without a driving license containing a “Vote Safe” logo. Such a feature does not exist and the claim is entirely false.

TikTok and YouTube state that they review ad content before it can go live, giving us an opportunity to assess whether their review process is effective without us actually publishing harmful ad content.

On this occasion, TikTok and YouTube rejected all the ads or suspended our accounts for violating their policies. This marks a welcome result – had they approved the content for publication, this would have demonstrated failures in their moderation process, potentially falling foul of UK law.

However, the platforms have not performed as well in similar tests elsewhere in the world.

Disinformation ads still threaten elections around the world

Ahead of India’s elections earlier this year, YouTube approved 100% of the ads Global Witness and Access Now submitted containing blatant election disinformation.

The platform performed better in a subsequent investigation in Ireland ahead of the EU elections, detecting 14 of 16 ads, but TikTok failed to detect any of the election disinformation content submitted in that test.

YouTube also approved a full set of election disinformation ads in our study ahead of the 2022 election in Brazil, despite detecting and halting the content in a parallel test around the 2022 US mid-terms.

TikTok has a mixed record as well – it performed badly in the same US test of the ads we submitted containing election disinformation. But in a second investigation, involving ads that contained death threats against election workers in the US, the platform suspended the test accounts for violating its policies.

These results demonstrate that the platforms have the ability to detect and moderate harmful content that can undermine election integrity when they want to. The inconsistent application suggests there are differences in where they choose to do so.

Overall we’ve found more policy enforcement in tests in Europe and the US than in tests in Africa, Asia and South America, which reflects poorly on these massive companies whose behaviour can influence the course of elections everywhere.

Election integrity is a global priority, not just a Western preserve, and the platforms must demonstrate they are resourcing and enforcing content moderation equally, regardless of where their users are or what languages they speak.

The change in results over time show that pressure from Global Witness and other civil society organisations, in the form of repeated tests and ongoing campaigning, can make a difference in getting platforms to improve their practices.

Aiuri Rebello, Odanga Madung, and Uri Ludger provided investigative support for this piece.