Sardinia, Italy has become a battleground for two visions of the future – a climate crisis-fuelled gas energy system, or a new system based on clean energy. This is a battle that is increasingly being played out all over Europe. By Sara Farolfi

For Rosolino Sini, a 35-year-long dream is finally coming true.

Benetutti, a small village in Sardinia’s remote Sassari province, will soon boast the first “smart grid” in Italy, entirely powered by renewable energy. “It’s a revolution,” says Sini, the person in charge of Benetutti’s electricity grid and the project’s visionary mastermind. “Not only it means that we will soon be totally self-sufficient, but we will also be able to sell the energy we produce.”

The origins of Benetutti’s revolution date back to the early 20th century: needing to light the road leading to his mill, a local miller began producing electric energy using the water passing through the mill. Astounded by the discovery, council officials decided to buy the patent. Sini is delighted when he thinks how far the village has come since then.

Today, Benetutti ranks first among all Italian towns for installed solar capacity per capita, thanks to a network of 104 solar power plants. The grid is controlled by a council-run company, which produces enough energy for its 1,100 customers and may soon be able to sell surpluses to external clients.

Benetutti ranks first among all Italian towns for installed solar capacity per capita, thanks to a network of 104 solar power plants

“Thanks to the smart grid, citizens in Benetutti will see savings of up to 30% in their electricity bills,” says the town’s mayor Vincenzo Cosseddu. Rosolini Sini, who was first employed 35 years ago by the local power supplier as a clerk, likens Benetutti to an ‘energy democracy.’ “It means freeing ourselves from resources, like gas or oil, that are not natural for us, and producing energy from what we have in abundance, such as the sun and the wind.”

Rather than just a small-scale example of good governance, Benetutti represents the symbol of an energy revolution with a much wider significance.

The climate crisis has been forcing dramatic changes upon everyone. European Union leaders have agreed to make the bloc carbon neutral by 2050. Sardinia will have to shut down all five of its coal-fired power plants by 2025.

Sardinia has become a battleground for two diametrically opposed energy models. On one hand, many scientists, academics and green activists believe the region can pioneer a new system based on renewable energy and widespread electrification (from electric cars, to heat pumps etc). On the other, gas has been presented by fossil fuel companies as a climate solution, claiming that it is a ‘low-carbon’ fuel. Today, Sardinia is the only Italian region without a gas distribution network after a series of failed attempts to implement one.

In May 2019 a new project for a gas pipeline in Sardinia was presented by Enura, a joint venture between Snam - Italy’s leader in gas transport - and Società Gasdotti Italia.

Strongly supported by the Sardinian Regional Council, the plan involves the construction of a nearly 600 kilometer-long pipeline stretching across the length of the island. A complex network of regasification plants, coastal depots and city grids would create the capacity to transport up to 1.8 billion cubic meters of gas across the region. Construction work kicked off in November 2019, when Snam awarded a first contract worth 5.5 million euros to Technip, a French energy engineering company.

However, many knots still need to be untied. The project’s cost is the most pressing, and controversial, issue. Enura comes with an estimated price tag of 590 million euros, which will be paid by taxpayers through levies in their future energy bills. Arera, the state regulator for the energy sector, has pointed out that the costs can be spread across the whole national territory only if a special government bill is introduced. Otherwise, Sardinian citizens alone will have to shoulder the burden of Snam’s project.

Arera is also weighing up the costs and benefits of the Enura project against a rival plan which would create an electric network between Sardinia, Sicily and the mainland through high-voltage cables. Accordingto a study commissioned by the regulator in order to compare the two projects, electrification along with the development of green hydrogen are better suited to fit the long-term decarbonization policies.

A study carried out by the Polytechnic University of Milan, and commissioned by WWF, imagines an energy model for Sardinia entirely reliant on renewable energy sources, alongside a bolstering of hydroelectric power stocks and the development of green hydrogen.

“The lack of a gas network has always been regarded as a chronic delay, but it should now be treated as a huge advantage,” says Alfonso Damiano, professor of electrical engineering at the University of Cagliari. “The data show us that production from sources of renewable energy meets around half of total energy demand in Sardinia.”

Even when it comes to heating, gas and diesel represent a small part of the energy mix, since biomass and heat pumps are most widely used, Professor Damiano says. “The reason is that electrification is financially more convenient and most people here know that,” he adds.

According to Sardegna Ricerche, Sardinia’s regional research agency, the Benetutti model could be replicated in at least a hundred Sardinian towns with similar geological features. A more widespread rollout of renewable energy use is often hindered by inconsistent power sources, which require appropriate storage facilities.

Biogas obtained from biomass is being trialled in order to stabilize the energy grid in Benetutti. However, Alfonso Damiano argues “a certain amount of natural gas needs to be used in the transition phase”. The question is how much gas exactly? 500 million cubic meters, according to an estimate by the University of Cagliari. As supply from renewable energy becomes more stable, reliance on natural gas will progressively fade until it will no longer be needed.

Natural gas is a misleading name: it may be perceived as clean, but gas is a fossil fuel, which produces greenhouse gas emissions. In 2017, natural gas was responsible for nearly 45% of all carbon dioxide produced in Italy, according to Ispra, the national institute for environmental protection. Oil and coal represented respectively 44% and 11% of all emissions. [11] Natural gas is also responsible for so-called 'fugitive emissions’ that leak along the supply chain of exploration, production and distribution of gas. A relatively small leakage rate of 3% across the whole of the supply chain can make natural gas as damaging as coal in terms of climate, according to E3G. Finally, natural gas has a tendency to lock in users: once costly and complex infrastructures have been built, it is difficult to get rid of them.

“Even though gas demand is declining, new plants keep being built”, says Mariagrazia Midulla from WWF Italy, “the consequence is that investments in renewable energy remain scarce”.

Fossil fuel consumption has been steadily declining in Italy due to the combined effect of rising temperatures, increasing energy efficiency and the gradual development of sources of renewable energy. In 2019 gas demand in Italy decreased by 2%compared to the previous year. The Covid-19 pandemic caused natural gas consumption to plummet further in early 2020.

Meanwhile, plans to build or repurpose gas power stations are booming in Italy, mainly for two reasons: the phasing out of coal-fired plants, like those in Sardinia, to be completed by 2025, and the ‘capacity market’, which allows gas power plants to receive funding even when they are not producing energy. “It is a volatile situation,” says Massimiliano Varriale, “we are facing a proliferation of power stations that can hardly be justified by energy demand”.

The push for more natural gas is not happening only in Italy. Gas companies issue forecasts showing a rise in gas demand to lobby for the construction of new infrastructure[16]. The strategy seems to be working: despite the policy objectives to fight climate change, new natural gas plants and distribution networks are being built across Europe. The reason is simple: governments are advised on energy infrastructure plans by the gas giants responsible for the construction of terminals and pipelines.

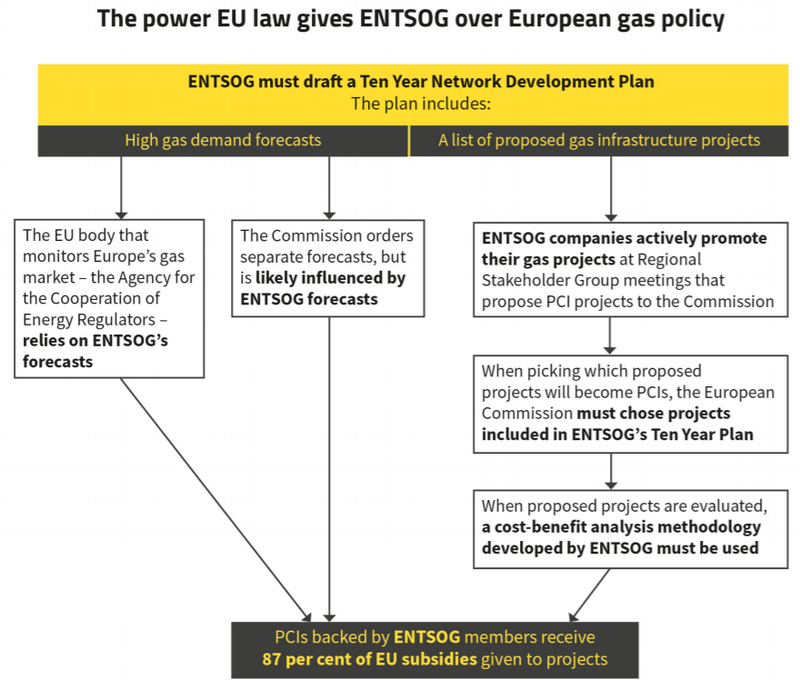

The European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas, or ENTSOG, is an obscure group of gas companies at the heart of energy policy decisions in Europe. Created in 2009, it helps the EU predict how much gas the bloc needs. ENTSOG has 44 member companies from 24 European countries and, since its creation, it has routinely overestimated gas demand, according to researchers from the Corporate Europe Observatory. The reason is simple: “75% of gas infrastructure built in Europe are projects backed by ENTSOG companies.”

Global Witness has calculated that projects backed by ENTSOG members have received almost 90 percent of the EU’s gas infrastructure subsidies – over €4 billion in total. These are the same natural gas companies that routinely overestimate how much gas Europe actually needs.

Italy’s gas giant SNAM is part of the ENTSOG network: between 2015 and 2019 it pocketed 813 million euros in EU funds for so-called Projects of Common Interest, according to the Global Witness study. An extra 714 million euros funded joint ventures in which SNAM took part.

In Italy, SNAM sits at the government tables where energy policy decisions are made. The company proposes new gas infrastructure projects based on data it provides and scenarios it draws up itself. In 2017 SNAM took part in the drafting of the National Energy Strategy, the white paper underpinning the recent National Plan for Infrastructure, Energy and Climate, largely reliant on SNAM data.

Finally, gas companies dedicate vast resources to lobbying activities. According to Italian NGO Re:Common, in 2018 SNAM and the other three main European gas producers spent 900,000 euros employing 14 lobbyists. “In 2019, these companies secured nearly 50 meetings with top political officials in the European Commission to discuss their latest pipeline projects or takeover offers,” researchers from Re:Common said. Snam alone spent between 200 and 300 thousand euros in 2019, according to data from the EU transparency register.

The new climate and energy framework set by the European Union and accepted by the Italian government in its policy documents, requires fundamental decisions about what type of future we want. Sardinia makes for a good example of the important crossroads we are at. Wasting millions on fossil fuel infrastructure that will not not meet the climate emergency goals or investing resources in long-term more sustainable models based on renewable sources.

An Italian version of this article was published by IRPIMedia (https://irpimedia.irpi.eu/a-tutto-gas-la-sardegna-e-leuropa-a-un-bivio/).