After Cambodian and Zimbabweans went to vote in the final days of July 2013 the election results in each country mirrored what many had predicted in the other.

In Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe, leader of the ruling party ZANU-PF, emerged with a handsome majority. This confounded expectations that, despite widespread allegations of vote rigging, the president might finally be beaten at the ballot box by Morgan Tsvangirai of the Movement for Democratic Change party.

In Cambodia, notwithstanding manipulation of the electoral roll and near total control of Khmer language media, Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) narrowly avoided defeat by the Cambodian National Rescue Party. Many concluded that it was only the most blatant forms of cheating that got the prime minister over the line.

Fast forward five years and, by a quirk of the electoral cycle (are authoritarian regimes just better timekeepers in this regard?) citizens of Cambodia and Zimbabwe this month go to the polls within 24 hours of each other: voting takes place on 29 and 30 July respectively.

Last time around, despite the two countries’ many differences, Zimbabwean and Cambodian voters faced a few challenges in common:

- An authoritarian leader, in post since the 1980s, with a Marxist pedigree and a liberator backstory (arguably more authentic in Robert Mugabe’s case), and a fondness for incendiary rhetoric, including threats to start a civil war if challenged, and regular denunciations of meddling westerners.

- An entrenching kleptocracy, belying the leader’s supposedly modest personal habits, with family members and/or associates helping themselves to the country’s natural resource wealth. Global Witness has investigated this in both Zimbabwe and Cambodia and last Friday published a new series of animations depicting the state looting going on in Cambodia.

- Well-oiled systems of control, which – in rural areas – were based on party structures dedicated to keeping voters in a state of fear and isolation.

- Containment of mostly urban political opposition and journalists via intimidation and legal actions rather than conspicuous acts of violence, but with sufficient exceptions to that rule to keep everyone on their toes.

- Armed forces that publicly expressed unswerving loyalty to the ruling party

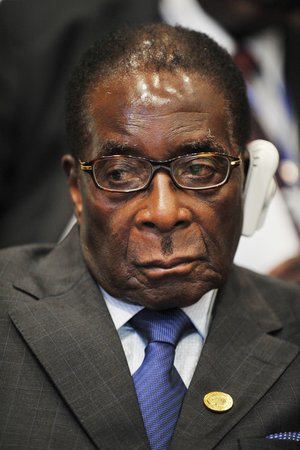

Former President of Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe’s efforts to secure the future fortunes of his wife sowed the seeds of his downfall. Credit: Jesse B. Awalt / Wikimedia Commons

What has changed?

In Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe is gone. While threatening to rule until death, he embarked on a series of hasty moves to secure the future fortunes of his second wife, ‘Gucci Grace’. The result was Mugabe being bitten by ‘The Crocodile’ – his long time security supremo Emmerson Mnangagwa – who assumed power following a coup in November last year.

President Mnangagwa, despite being implicated, through command responsibility, in everything from the Matabeleland massacres of the 1980s to the army’s covert acquisition of a stake in Zimbabwe’s Marange diamond fields in the 2000s, is presenting himself as Zimbabwe’s fresh start. Overt political repression has dialled down and the new president has launched, in the face of some scepticism, an anti-corruption campaign. Zimbabwe, he says, is now “open for business”. For their part, Zimbabwe’s Defence Forces have pledged to respect the election result whatever the outcome.

At the same time, ZANU-PF and the security forces still hold all the aces, including the country’s natural wealth. A recent parliamentary hearing confirmed that the army and Central Intelligence Organisation – that Mnangagwa himself previously oversaw – controlled major stakes in diamond mining companies. The hearing also inadvertently indicated, as our recent blog explains, that ZANU-PF may have awarded itself a share into the bargain.

What would Mnangagwa need to do to convince Zimbabweans and write a new page in Zimbabwe’s history? Given the likely connection between the security forces’ secret siphoning of diamond revenues and their support of ZANU-PF, one very tangible step would be to make the diamond and other natural resource industries transparent and accountable to the public. It shouldn’t require investigations by groups such as Global Witness or parliamentary probes to uncover just who is benefiting from natural resource wealth when 63% of Zimbabweans are surviving beneath the poverty line.

At least Zimbabwe’s voters have a reason to turn out and put the electoral system to the test once more. In Cambodia, Hun Sen’s government has finally outed itself as the dictatorship many long perceived it to be, by abolishing the main opposition party and residual independent media outlets – notably FM radio stations – and ruthlessly policing social media.

Following a similar script to the 1998 elections – which took place in the aftermath of a violent coup by Hun Sen – 19 small parties are now shuffling onto the stage to form an electoral chorus line behind the CPP. As one close observer puts it, these parties are, with one or two exceptions, “tools, compromised or irrelevant”. Pantomime it may be, but as Hun Sen understands very well, the rest of the world cares even less about elections in Cambodia than it did two decades ago.

To suggest that Cambodia’s voters can mount effective demands for change in the government’s behaviour through this non-election might seem like a cruel joke – even the most vocal activists are keeping a low profile amidst a government crackdown on any flicker of dissent. But the same can’t be said of the country’s international patrons and creditors. For reasons of self-interest if nothing else, it is time the Chinese authorities learned the lessons of their political and economic headaches in Myanmar, Sri Lanka and, most recently, Malaysia, and stopped bankrolling a government that systematically robs and oppresses its people.

For their part, western governments and Japan can no longer use China’s influence as an excuse for their failure to stand up for Cambodians. They can and should act, not least by subjecting Hun Sen’s family, friends and henchmen to targeted sanctions including asset freezes and visa bans, in the style of the U.S. Global Magnitsky Act.

As well as rigging the forthcoming election in Cambodia, Prime Minister Hun Sen has recently accelerated his attempts to forge a dynasty. Credit: Phnom Penh Post

And what of the future for Hun Sen himself? Is he, like Mugabe, destined to be the architect of his own downfall? Despite being 28 years younger, Hun Sen also appears to be a man in a hurry, recently promoting sons (including heir apparent Hun Manet) and a son-in-law to senior posts in the security forces. Senior military brass are being shuffled sideways and downwards into parliamentary seats to free up some space at the top. It is not clear if all these career changes are voluntary.

Factionalism in the Cambodian People’s Party generally takes a less spectacular form than in ZANU-PF, where the conflagrations are seen by some to be quite literal (much speculation surrounds the house fire that killed ex-army chief and presidential power broker, Solomon Mujuru), but that’s not to say it’s entirely absent either. The question is whether Hun Sen has it all worked out or whether he is pushing his own party too far in his drive to forge a dynasty.

Given what happened in 2013, many may think twice about predicting the outcome of Zimbabwe’s forthcoming vote. In Cambodia, by contrast, there is little chance of a bogus election turning up any surprises, although what happens beyond polling day is far more open to question. Could a future chapter in Hun Sen’s political saga even emulate the final act in Mugabe’s?