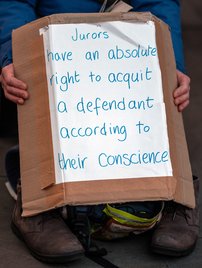

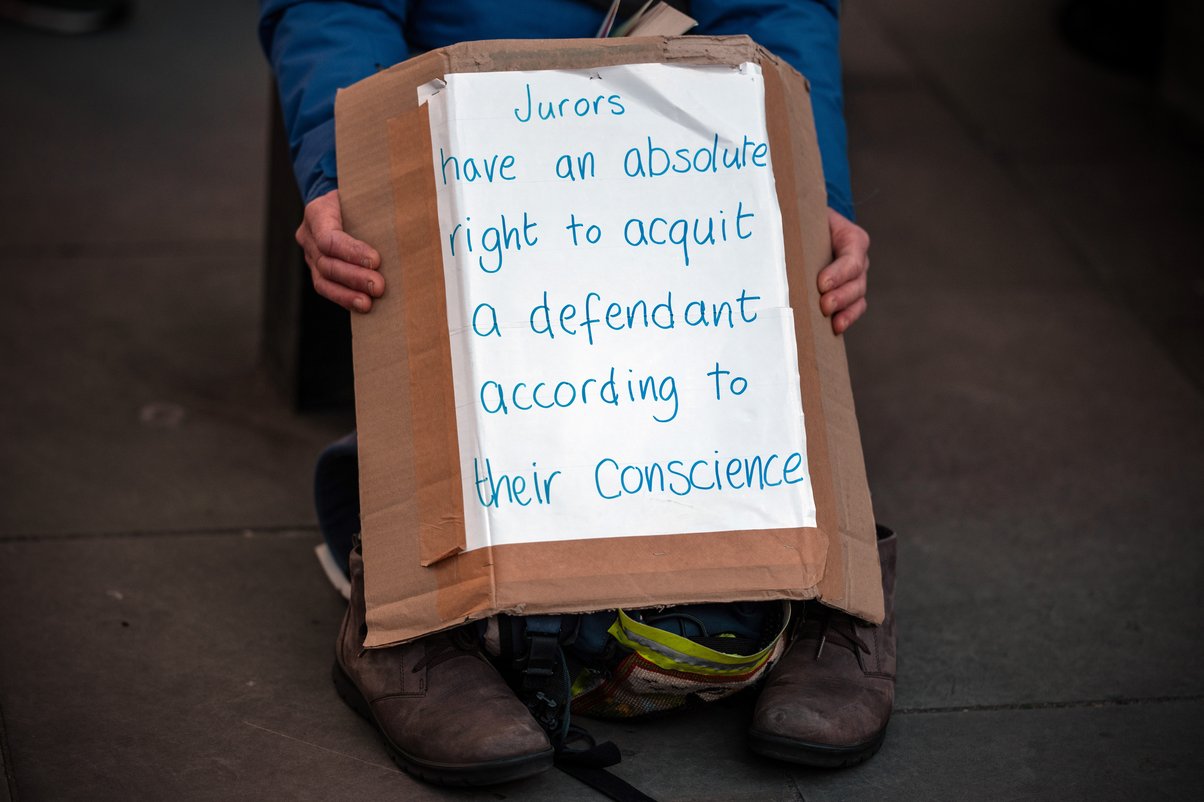

UK Court ruling on climate protestors sets dangerous precedent

Six climate protesters saw their sentences moderately reduced, while ten others had their jail time upheld, following a crucial Appeal Court test of the UK’s right to protest

Trending this week

-

Slash and sell

A Canadian asset manager part run by green finance champion Mark Carney cleared thousands of football fields worth of tropical forest in Brazil, our investigation can reveal

-

Narco-a-lago: Money Laundering at the Trump Ocean Club Panama

We investigate how profits from Colombian cartels’ narcotics trafficking were laundered through a development that bore Donald Trump’s name

-

A rush for lithium in Africa risks fuelling corruption and failing citizens

Three emerging lithium mines in Zimbabwe, Namibia and Democratic Republic of Congo risk fuelling corruption and causing a range of other environmental, social and governance problems

Defending our planet's frontline

Climate emergency in focus

-

Transition minerals: A climate solution that could cost the earth

Without better consultation and regulation, plans to expand mining for minerals central to the energy transition could be disastrous

-

What is climate disinformation?

Climate disinformation is hindering our ability to combat the gravest threat of our time

-

The problem with hydrogen

Hydrogen could be an important part of the renewable energy transition, but not if the fossil fuel industry has its way

Seeing and speaking truth: How we are grounding our new identity

Our brand refresh strengthens our mission to build the power of people fighting to dismantle the influence of climate-wrecking industries

Latest articles

UK Court ruling on climate protestors sets dangerous precedent

Six climate protesters saw their sentences moderately reduced, while ten others had their jail time upheld, following a crucial Appeal Court test of the UK’s right to protest

BP CEO bags obscene £5.4 million at UK households’ expense

BP CEO Murray Auchincloss earned 143 times more than the average British worker last year, laying bare the financial inequality at the heart of the energy crisis

The time for change is now

The climate crisis is no longer an event on the horizon. It’s here, it’s now. Learn how you can support fearless investigative campaigning to expose the industries fuelling climate breakdown.

About us

Global Witness is an investigative, campaigning organisation that challenges the power of climate-wrecking companies, and stands with the people fighting back