The European Union’s new corporate accountability law is a major win. But how will it help protect land and environmental defenders?

Powerful companies often seem to be above the law – with little accountability for the harms they cause to people and the planet through their operations.

But change is on the horizon with a new law in the EU - the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) - which aims to make it easier for communities to hold companies around the globe accountable.

What does this change mean for human rights, environmental and land defenders – the people challenging the unchecked extraction of natural resources? We explain below.

How will the law help defenders?

Under this law, large companies with significant operations in the EU will have to conduct “due diligence” – meaning they must identify and address any potential and actual negative impacts their operations could have on land rights, the environment and human rights.

This includes identifying harmful behaviour of business partners as well as taking steps to reduce risks and preventing harm across their own business activities. The goal is to make sure that companies are held responsible for their actions and work towards sustainable practices that ensure a shift towards a just transition and a fairer economy.

Companies are obliged to engage with rightsholders such as workers, affected communities and human rights or environmental defenders in their due diligence process.

As well as ensuring that companies prevent, end and mitigate adverse impacts, the law also provides access to remedy. If rightsholders believe that there are potential or actual risks to their human rights, their livelihoods or the environment, they can submit a complaint to the company and seek remediation.

Importantly, the law also allows affected communities to take companies to court in the EU if they are found to be directly responsible for the harms caused.

Which companies are covered?

The CSDDD will require large EU companies with more than 1000 employees and €450m in turnover globally to conduct due diligence to protect human rights and the environment, as well as address their potential and actual adverse impacts that arise from this assessment.

Non-EU companies with a net turnover of at least €450m in the EU will also be covered.

Is the law in place?

Not yet. While the law has been finalised, it is also only a template that the 27 EU Member States will need to convert into their own legal systems over the next two years – and it will still take time for it to come into force.

Its application will be staggered, applying to the largest EU companies with 5000 employees and €1.5 billion in turnover in 2027, followed by companies with 3000 employees and €900 million in turnover in 2028.

By 2029, companies with at least 1000 employees and €450 million in turnover will have to fulfil the obligations set out in this law. Smaller companies may also be affected in their capacity as contractors or business partners.

What is stakeholder engagement and how will it help defenders?

The recognition and involvement of affected stakeholders when assessing impacts of a company’s operations is one of the main ways the CSDDD will help defenders.

Stakeholders are defined as individuals, groups or communities whose rights or interests are or could be affected by the products, services, and operations of a company, as well as its subsidiaries and business partners.

This definition includes not only employees, trade unions, and consumers but also civil society organisations and the legitimate representatives of these stakeholders.

Companies will be required to effectively engage with these affected stakeholders. Engagement will be carried out at various stages of the due diligence process, from gathering information on adverse impacts to developing plans to prevent or correct any issues.

Furthermore, companies must provide relevant and comprehensive information to stakeholders, who can also ask for additional information. Companies will also be encouraged to consult with experts who can provide credible insights when necessary.

Will it be safe to engage with companies?

To allow affected stakeholders to fully participate, the CSDDD mandates companies to seek to remove any obstacles to engagement and shield participants from any potential backlash. This includes upholding confidentiality for those who prefer to remain anonymous while raising concerns about a potential or ongoing project.

It is crucial for companies to prioritise and protect the rights, safety, and overall well-being of all stakeholders involved in the process. Failure to do so could expose companies to legal liabilities and challenges.

What if you need to issue a complaint?

Complaints can be submitted directly to companies through a so-called “complaints mechanism.” The law obliges companies to set up such a procedure in which they can be contacted directly and made aware of risks and impacts to communities and the environment.

These complaints can relate not only to the company itself, but also to its subsidiaries and business partners. The complaint may then contribute to a plan to prevent further adverse impacts or remedy adverse impacts.

There is also a further option to submit concerns regarding a company in the EU Member State in which the company is based. So-called “substantiated concerns” can be submitted to the competent authorities in the respective EU country to draw attention to potential or actual harm caused by a company.

This authority has the power to impose financial sanctions on the company if they find that it is not living up to its due diligence obligations.

What about out-of-court remediation?

EU countries will have the power to order a company to provide appropriate remediation to affected rightsholders and communities if the company fails to do so itself.

This remediation could include compensation paid by a company to affected rightsholders, and ordering a company to cease an action.

This is in addition to potential financial penalties a company could face and the option for affected individuals to seek justice before a national EU court.

Importantly, this means that even if a company pays compensation or grants other forms of remediation out of court, affected rightsholders or communities will still be able to take the company to court in the EU.

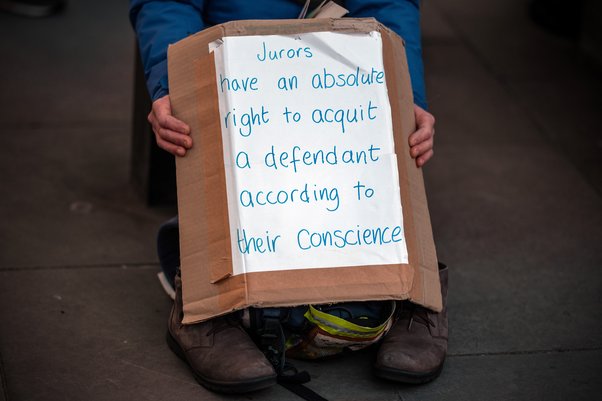

Taking a company to court in the EU

The law gives affected individuals and communities the right to sue a company for damages it is directly responsible for.

If a company intentionally or carelessly ignores a known risk or fails to stop it, it can be held accountable for any harm caused to a person or community. Defenders are therefore empowered to decide whether to take legal action against the company in their own country or in the EU.

If an affected individual or community wants to sue a French company, for example, this will be heard by a French court.

This option is intended to help affected communities or defenders who feel that their national legal system would put them at a disadvantage.

What other options are there to make access to justice easier?

The CSDDD allows civil society organisations and trade unions to bring lawsuits to EU court on behalf of victims if they give their permission. This could be helpful if the rightsholders and communities concerned do not have the resources to do this themselves.

Furthermore, the law sets out a time limit of at least five years for bringing a lawsuit, and it doesn't start until the harm stops and the person bringing the lawsuit becomes aware of it. This gives people more time to get ready to bring a case to court.

Finally, the law also makes it easier to get important information from companies. Courts can make companies share internal documents that could be used as evidence for the victims' claims.

The CSDDD should empower defenders to push back against corporate abuse linked to Europe’s biggest companies, by providing them with a platform to voice their concerns, demand transparency, seek remediation and enforce justice in front of courts.

While it has some limitations, the new law will help us move towards a fairer and more sustainable future in which the balance of power shifts in favour of defenders and affected communities.