Today we’re publishing another secret document revealing the financial networks behind Sudan’s most powerful militia – the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). An apparently genuine RSF spreadsheet shows how they bought over 1,000 vehicles, including hundreds of Toyota pickup trucks which the militia frequently convert into armed ‘technicals’.

We obtained the spreadsheet via satirical Sudanese online channel Al Bashoum, which had published a screenshot of one of the pages, but had not put out the full document. Al Bashoum was also the source of some of the seemingly authentic bank documents we analysed in our last report: Exposing the RSF’s Secret Financial Network. We’re publishing the spreadsheet in both its original and in an English translation.

When corroborating the documents, we used a variety of open source intelligence (OSINT) techniques to investigate the names of companies and individuals mentioned. We also checked to see if any of the vehicles appear in contemporaneous photos or videos. We’d like to share what we did, and also lay out some of the questions which we were unable to answer in the time available. We hope that others can help reveal more about the network apparently behind the RSF.

Why do we think the RSF spreadsheet is genuine?

It is possible that this document is too good to be true. After all, leaked financial information for militaries or paramilitary groups is exceedingly rare. (One of the few examples known to Global Witness is this analysis, drawing on captured documents, of the finances of Al Qaida in Iraq in 2005/6, the violent jihadi group led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.) Could the document be part of an elaborate misinformation campaign?

In addition to investigating the provenance of the document, contacting individuals and companies named therein, and talking to sources familiar with the RSF leadership, the spreadsheet itself contains information which can be corroborated.

There isn’t one single section of the document that indicates its authenticity. Rather, it is the accumulation of interlocking references to companies, individuals and types of vehicles which, when triangulated using other sources, led us to the conclusion that the document is almost certainly authentic.

When we investigated the companies named using corporate records and analysis of registered website domains, we found familial connections to the leadership of the RSF. When we followed up references to named individuals we found many of them easily on social media, many of them linked to family members of the RSF leadership, and some of them connected to one of the companies named in the spreadsheet. And when we examined the vehicles named in the spreadsheet we found pictures of the same make and model of vehicles, from a variety of independent sources, at almost every stage of the supply chain from Dubai to Sudan. Taken as a whole, it is our opinion that the document is highly likely to be genuine.

Where we could identify the companies or individuals, we wrote to them for comment on why they appeared in the spreadsheet. After repeated attempts to contact 42 companies, only nine companies gave full or partial responses. These responses are integrated in the blog where appropriate, and we annotated the spreadsheet with the responses we received. The majority of the responses stated that they had no knowledge, or means of knowing, that they dealt directly or indirectly with RSF or their procurement agents. Given the use of middlemen this is almost certain to be the case and we do not suggest any wrongdoing on the part of any individuals or companies mentioned in this blog or spreadsheet, unless otherwise discussed.

In two responses companies listed as suppliers in the spreadsheet told Global Witness that the goods were bought by Tradive General Trading. This is further confirmation of the authenticity of the spreadsheet. As discussed further below, our last publication revealed that Tradive is controlled by Algoney Hamdan Daglo, the younger brother of Hemedti, the leader of the RSF.

The vehicles

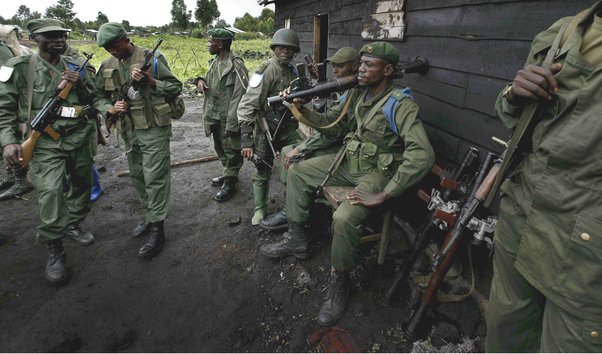

Rapid Support Forces (RSF) “technicals”, June 22, 2019. YASUYOSHI CHIBA/AFP via Getty Images

The RSF spreadsheet describes the purchase and importation of more than 1,000 vehicles during the first half of 2019. The majority of these vehicles were Toyota Hilux and Land Cruiser pick-up trucks, often converted by the RSF into ‘technicals’, 4x4 military vehicles with mounted machine guns on the back.

We reviewed over one hundred RSF videos posted on the militia’s official Facebook page, and others posted by Sudanese citizens on social media. We were looking for any corroboration of the authenticity of the document through identifying particular models listed in the spreadsheet.

We found photos and documents which provide snapshots of each stage of the journey from Dubai to Sudan of the same make and model the vehicles named in the spreadsheet.

Toyota responded to our request for comment, stating that: “Toyota has a strict policy not to sell vehicles to potential purchasers who may use or modify them for paramilitary or terrorist activities, and have procedures in place to prevent their products from being diverted for unauthorised military use.” They further told Global Witness that Toyota “complies with export control and sanctions laws, and requires dealers and distributors to do the same”. Toyota emphasised that it has clear guidelines not to sell vehicles to military or police organisations in Sudan.

Stage 1: The vehicle showrooms of Dubai

It is possible to find online the same model of vehicles advertised by the same companies named in the spreadsheet. For example, one line lists “Purchase 50 Toyota Land Cruiser Pickup car, standard, Beige colour, 2019 model with 2018 paintings”, and the supplier column states that “Al Karama Motors Showroom (50 cars×103000 dirham)”. Sure enough, Al Karama – a vehicle retailer based in Dubai – currently lists identical models of the type bought by the RSF. This is useful circumstantial evidence, which helps support the plausibility of the contents of the RSF spreadsheet.

Source: Photos taken from Al Karama motors website in October and November 2019

Al Karama Motors denied knowing that it dealt with the RSF. There is no suggestion that Al Karama Motors has knowingly supplied vehicles to the RSF or are guilty of any wrongdoing.

We wrote to all identifiable vehicle suppliers named in the spreadsheet and, like Al Karama, those who replied denied knowledge that they were supplying to the RSF. One supplier wrote back to confirm the purchases, and supplied details such as the number of vehicles purchased on certain dates. These matched the information in the leaked spreadsheet.

Source: still from video posted on Facebook, 2019

Stage 2: Getting ready to transport the vehicles from Dubai

A video posted on 20 March 2019 on Sudanese social media shows dozens of beige Toyota Land Cruisers and Hilux pickup trucks (white with a distinctive red stripe painted on the side) parked up ready to be shipped to Sudan. We geo-located the video to an industrial area of Dubai. The person narrating the video says that there were 600 vehicles in total (some of which had already been shipped to Sudan) and that they were told by the shipping company that the vehicles were for use by Hemedti’s militia.

Many of the vehicles in the video display a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Standardization Organization (GSO) energy efficiency sticker. This sticker was only introduced in the UAE from 2017 onwards. This indicates that RSF vehicles seen with this sticker are likely 2018 and 2019 models and were imported from GCC member states.

We have found a very similar energy sticker in videos of convoys of police and RSF militia posted online after the 3 June massacre.

By examining a wide range of RSF related social media accounts Global Witness has identified several Toyota vehicles used by the RSF and police with this same energy efficiency sticker more clearly displayed.

Source: Pictures posted on the Facebook pages of RSF militiamen showing their technical still with the GSO energy efficiency sticker, from left to right - posted October 2019, July 2019, June 2019

Can you help? Remaining questions: If there is a clear photo of one of these stickers available from open sources, it may be possible to use the GSO QR scanner to identify the date of manufacture of the vehicle.

Stage 3: Shipping the vehicles to Sudan

Source: original photographer, photo taken on 25 March 2019

There is a red sticker on the RSF vehicles in two of the photos above. This is from the Red Sea Service Centre – an import/export and customs clearance company with a main branch in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. According to their social media postings this company uses a ship called the “Egyptian Al Karama”. (Despite the name, there is no connection with Al Karama motors.) In the leaked RSF spreadsheet the Al Karama is listed as having shipped 75 vehicles on 23 March 2019. Using historical shipping data from Marine Traffic, a shipping database, we can confirm that the Al Karama travelled from Jeddah in Saudi Arabia to Sawakin, Sudan (also known as Osman Digna Port), arriving on the 23 March 2019. (There is a land route from the UAE to Jeddah, so it is likely that the vehicles were transported overland first). In our opinion this means that the information in the RSF spreadsheet is plausible. When Global Witness contacted the Red Sea Service Centre, they referred us to the company making the shipment, and denied any knowledge that the vehicles might be put to military use.

We found one picture online of about 100 Toyota cars, vans and pickup trucks lined up at Sawakin port. According to the photographer, the picture was taken from on board the Namma Express ship on 25 March 2019, i.e. just after the arrival of vehicles on the Al Karama. However, we cannot definitively say whether this photo shows those particular vehicles, or any of the other shipments, at Sawakin port. Global Witness does not allege any wrong doing by any shipping company.

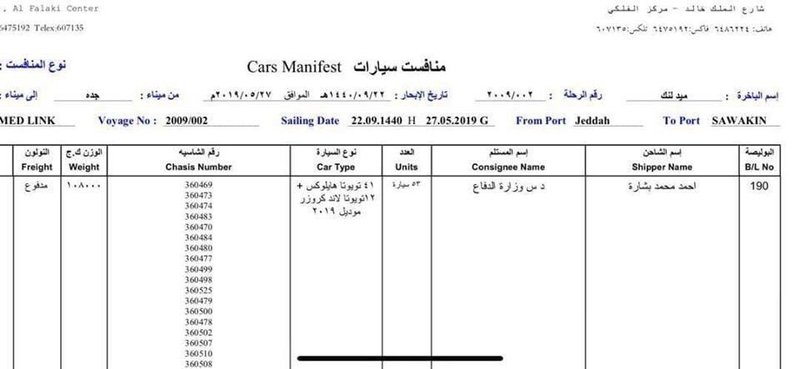

Another ship featured in the social media posts of the Red Sea Service Centre is the ‘Med Link’. This vessel is named in a shipping document entitled a ‘cars manifest’, which was widely circulated on Sudanese social media. This specifies that 53 Toyotas (41 Hilux and 12 Land Cruisers) were shipped from Jeddah to Sawakin on 27 May 2019. The consignee name in the manifest is “RSF – Ministry of Defence”. This timeframe tallies approximately with the RSF spreadsheet which has an entry for “53 Toyota vehicles shipping” against a date of 6 June 2019. In our opinion, it is likely that the 53 vehicles mentioned in this shipping manifest refer to the same shipment.

Vessels named in a shipping document entitled a ‘cars manifest’, which was widely circulated on Sudanese social media

To provide further reassurance that the shipping document is itself genuine we uncovered another identically formatted manifest from a different online source. This one lists the same vessel, the Med Link, travelling from Jeddah to Suez in Egypt on 31 May 2019. This other manifest lists the voyage number as 2009/003 – the next number in sequence after the Jeddah-Sawakin journey we are interested in: 2009/002. We again used historical shipping data from the Marine Traffic database to confirm that the Med Link had travelled on those dates from Jeddah to Sawakin and subsequently back to Jeddah and then on to Suez.

Can you help? Remaining questions: Are there other photos in the public domain of the vehicles being shipped to Sudan? Are there any more shipping documents available?

Stage 4: Transport from Sawakin to Khartoum

There are photos from early 2019 circulating on Sudanese social media of a vehicle transporter, loaded with beige Toyota Land Cruiser pickup trucks. A close-up shows that one of the transporters has a red and green RSF number plate.

In RSF propaganda videos we frequently see the distinctive red and green number plates used by the RSF (in Arabic: د س ق = قوة الدعم السريع = RSF). One example is shown below.

Source: RSF video showing RSF convoy with distinctive red and green registration number plates. Posted 18 September

We found photos online of the transporters carrying the Toyota Land Cruisers and then OSINT expert Logan Mitchell geolocated them to Air Street, Khartoum.

Source: Inset: Image of vehicle transporter circulating on Sudanese social media. Main picture: Google Earth satellite imagery, with coloured boxes geolocating the paving, lamp posts, and traffic lights shown in the photo

Source: Inset: Image of vehicle transporter circulating on Sudanese social media. Main picture: Google Earth satellite imagery, with coloured boxes geolocating the minaret, lamp posts, and pylons shown in the photo

We can also say that these pictures were taken at some point after 10 January 2019. By comparing satellite imagery from 10 January 2019 to an image taken on 22 January 2019, we can see from the shadows that the leaning / broken lamp post in the middle was damaged sometime between those two dates.

Source: screenshot of satellite images of Air Street, Khartoum from 10 January (left) and 22 January (right) 2019. In the left picture the shadows cast by the lamp posts are parallel, indicating that they are all upright. In the right picture, while faint, the image shows that the shadow middle lamp post is no longer parallel with the others, indicating that it is now leaning

By itself, this isn’t proof that these were vehicle transporter(s) carrying the exact same beige Toyota vehicles as described in the manifest or in the RSF spreadsheet, but it is useful contextual information – ruling out the possibility that the photos were taken in previous years or in different countries.

Can you help? Remaining questions: Are there other photos in the public domain of the RSF vehicle transporters?

Stage 5: similar vehicles in use in Sudan

In general, the RSF spreadsheet provides too few details to link the exact same vehicles in the spreadsheet with the specific vehicles seen in videos and photos posted on social media, or those used on the evening of the June 3 massacre. However, we have managed to identify a few specific vehicle models which are likely to be those listed in the spreadsheet.

For example, the most expensive vehicles bought by the RSF were the five luxury Toyota Land Cruisers (model VXR 5.7L) which according to the spreadsheet, were purchased, on 22 April 2019 from Car City, Dubai for 278,000 Dirham (USD$76,000) each.

Source: screenshot of Car City LLC website home page showing a luxury Land Cruiser

Car City failed to respond to a request for comment.

The same model was found on the website homepage of one of the Dubai vehicle vendors listed in the spreadsheet - Car City LLC. This helps to confirm that this particular vendor – Car City – sells this type of vehicle. There is no suggestion that Car City has knowingly supplied vehicles to the RSF or are guilty of any wrongdoing.

Hemedti can be seen emerging out of the same model of the luxury Toyota Land Cruiser in several videos posted in summer and autumn of 2019.

Source: still from RSF video published on 9 September 2019 showing Hemedti and entourage arriving in vehicles including a luxury Toyota Land Cruiser with an identical front grille to the model VXR 5.7L named in the spreadsheet

This isn’t proof that these are the exact same vehicles, but it is useful contextual information that these types of vehicles are used by the RSF high command to transport Hemedti and his entourage.

Similarly, according to the spreadsheet, the RSF imported 50 HINO trucks in spring 2019 and bought hundreds of ICOM ‘walkie-talkie’ radios.

In response to Global Witness’ request for comment, Hino denied selling trucks to the RSF. Hino told Global Witness that they “did not have any involvement in the alleged transactions in spring 2019, and did not export any vehicles to Sudan in 2019. Further, Hino has never had any transactions and relationships with the RSF and other armed forces in Sudan.

The company also told Global Witness that “Hino maintains a contractual prohibition against its distributors around the world to re-export Hino vehicles to other countries” and that “Respecting and preserving human rights in our global business is a top priority for Hino.”

On the social media accounts of RSF militiamen, we identified several pictures of HINO trucks with RSF number plates, and militiamen using ICOM radios. ICOM denied selling products directly to RSF, but said the RSF may have acquired ICOM products through other channels of distribution.

Again, we cannot be certain that these are the exact same models described in the spreadsheet, but this is useful contextual information that the RSF use this type of equipment.

Source: Left: HINO Truck with RSF numberplate; source Facebook, posted 31 May 2019. Right: RSF militia member with ICOM radio – Facebook, posted 21 August 2019

Can you help? Remaining questions: Do you have video or photos of the vehicles used in the run up to the 3rd June massacre – particularly those nearest to the clearing of the sit-in site?

The companies connected to the RSF: GSK, Al Gunade, Tradive

The spreadsheet also helps to shed light on three companies which are connected to the RSF.

GSK: investigating websites and IP addresses to uncover a link to the RSF

One of the transactions in the spreadsheet states that “A special amount was delivered by Mohamed Hashim Koko - Rwanda - A - to Algoney - 33 thousand dollars” and says that the “transaction [was] done for GSK Advance”.

Source: Algoney Hamdan Daglo, Twitter profile picture

GSK is an information technology and CCTV/access control security company based in Sudan (unrelated to GlaxoSmithKline, the multinational pharmaceutical company). Hemedti’s younger brother Algoney Hamdan Daglo, is listed (as “Algoney hamdan”) as one of the Chief Executives of GSK in an earlier version of the GSK website stored on the Internet Archive.

Algoney holds the rank of Major in the RSF, and is in charge of the RSF’s procurement processes, according to two people in a position to know contacted by Global Witness. We put this to Algoney, who failed to respond.

Using OSINT techniques, we found that GSK is connected to the RSF and two other companies named in the documents: Al Gunade and Tradive General Trading LLC (both examined in more detail below).

According to its own website, GSK has done work for the RSF and various Al Gunade companies, including designing websites for both. GSK also designed and registered the official RSF website. An earlier draft version of the RSF website was found at a sub-domain of the GSK site (archived version here). GSK also registered the domain name tradive.com, almost certainly for Tradive General Trading.

It is quite common for web design firms to register domain names on behalf of their clients, so it’s theoretically possible that GSK is just a web design and hosting company providing a service to clients.

Often, when researching the servers of web hosting companies, one finds over 1000 websites on a shared server. However, analysis of publicly available internet infrastructure data reveals only a small number of website domain names registered using the @gsk-sd.com email domain suffix, with most resolving to the same IP address: 190.2.149.40.

The shared IP address indicates that there is a dedicated server for websites hosted by GSK, which only hosts about a dozen websites. This increases the possibility that RSF and GSK are more closely linked than GSK simply designing the militia’s website.

The combination of the financial transfer made by the RSF on behalf of GSK, the involvement of Hemedti’s younger brother in GSK, and the shared internet infrastructure, support our hypothesis that the organisations have a closer relationship than a typical client and IT provider.

Despite repeated attempts to reach them, neither GSK nor Algoney Hamdan Daglo has commented on allegations put to them by Global Witness.

Source: Table showing selected data about websites registered by emails using the @gsk-sd.com suffix. Data gathered using Domain Tools and RiskIQ software. No suggestion of any wrongdoing is implied by inclusion in this table. Accurate as of October 2019.

Can you help? Remaining questions: What are the activities of the other companies with domain names registered by GSK? Do they also have any relationship with the RSF or Hemedti’s family?

Tradive: using internet infrastructure links and corporate documents to discover a link to Hemedti

As you can see from the table above, the other domain name that we linked to GSK through analysis of internet subdomains and IP addresses, is tradive.com - highly likely to be the domain name registered on behalf of Tradive General Trading LLC.

The bank documents analysed in our last publication appear to show money flowing back and forth between the RSF bank account and an account (held at El Nilein Bank) of a company called Tradive General Trading LLC. Credit notes for Tradive seem to show that it received almost 50 million dirhams (US$11 million) from the RSF in four instalments in April and July 2019. An ‘outward customer transfer report’ from El Nilein Bank July 2019 has the RSF bank account being paid 48 million dirhams (US$11 million) by Tradive; and describes the payment as “transfer to sister company.” (Neither of the banks named in the documents responded to requests for comment).

Global Witness obtained corporate information on Tradive from the Dubai Department of Economic Development (DDED), this confirmed that Mr Algoney Hamdan Daglo Musa – Hemedti’s younger brother and Chief Executive of GSK – is a director and ultimate beneficial owner. Technically, ownership of Tradive is split: Algoney as a Sudanese national owns 49%, while 51% is held by an Emirati national (the Sponsor). The UAE government requires foreigners who set up Limited Liability Companies (LLCs) to have a UAE national as a sponsor, owning 51% of the company. According to information provided to us by a corporate due diligence agency, the sponsor has no involvement in the running of the business.

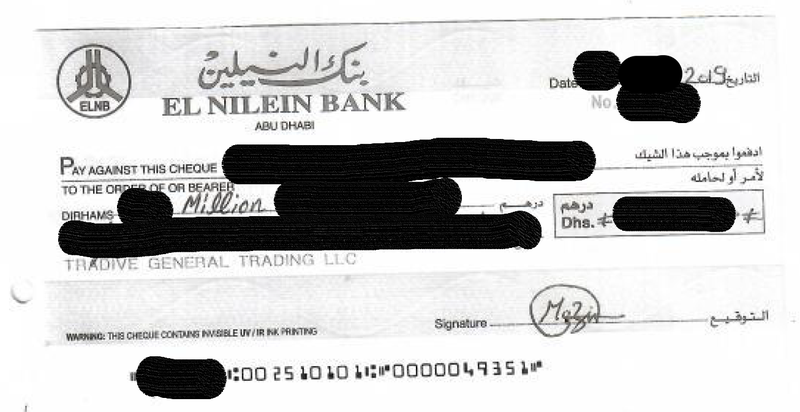

When we wrote to the suppliers listed in the leaked spreadsheet, one wrote back with copies of the cheques used to purchase the vehicles. Payment came from Tradive General Trading LLC’s bank account at El Nilein Bank, which also helps to corroborate the authenticity of the leaked credit notes and outward customer report discussed earlier.

Source: copy of the cheque used to purchase vehicles, provided by one of the suppliers

Tradive General Trading LLC is listed as an official partner of the Thuraya satellite phone company (there is no suggestion that Thuraya are aware of any link to the RSF) and has some employees listed on LinkedIn. This suggests that Tradive is not an empty shell company, but rather conducts real economic activity alongside having a close relationship with the RSF. Despite repeated attempts to contact Tradive, the firm did not respond to our requests for comment.

Can you help? What’s the origin of the money paid by Tradive to the RSF?

Al Gunade: official Sudanese corporate documents help prove the link to Hemedti and the RSF

Hemedti’s rise to power is frequently explained partly by his control of the Jebel Amer gold mines in Darfur, and a gold trading company often referred to as Al Junaid. Letters from the Al Gunade company published on the GSK website indicate that the company group refers to itself in English as Al Gunade — the same pronunciation but different spelling.

Global Witness has obtained an official Sudanese corporate document from the commercial registry department of the Ministry of Justice. Al Gunade is owned by three members of the Daglo family: Hemedti’s brother, Abdul Rahim Hamdan Daglo, and Abdul Rahim’s two young sons. According to the registry document Hemedti himself is on the Board of Directors.

When approached by Global Witness a spokesperson for Al Gunade said that Hemedti had ended his formal role in the company in 2009, and that the corporate document hadn’t been updated.

Source: screenshot of Abdul Rahim Hamdan Daglo, YouTube, 27 April 2019

Abdul Rahim himself is deputy head of the RSF, and is alleged to be partly responsible for the recent killings of over 100 protestors in Khartoum. The BBC reported an interview with an anonymous RSF officer who said that an “Abdul Rahim Dagalo” gave the order to clear the Khartoum sit-in – although the BBC was unable to independently corroborate this claim. (Please see this Human Rights Watch report for a discussion of the massacre and an analysis of official and medical sources on the number of fatalities).

In his role as deputy head of the RSF, Abdul Rahim Hamdan Daglo is also widelyreported to have received money from the former Sudanese dictator, Omar al-Bashir. President al-Bashir’s former office manager testified in al-Bashir’s corruption trial in Sudan that the former President gave him 5 million euros to give to an “Abdul Rahim Hamdan Daglo”, handing over the funds in the presence of the latter’s brother, Hemedti.

In addition to the overlap in the senior personnel, Al Gunade and the RSF also seem to make payments to each other. In the RSF spreadsheet, Al Gunade is named as the recipient of 210,000 Dirham (about US$60,000), and the line item states that “A special amount equivalent to 50 thousand euros is considered debt on Al Gunade”. Another line indicates that the RSF earmarked 686,000 Dirham (US $186,000) to wire to someone in China, for payments to Al-Gunade (Note: this line item is found in line 9 of the ‘Transfers’ tab of the full spreadsheet).

The Al Gunade spokesperson denied that the firm provides any financial support to the RSF but did confirm commercial ties between the company and the RSF. He claimed that certain money movements between Al Gunade and the RSF would have related to commercial transactions. In response to a separate investigation by Reuters, the company’s General Manager denied any link to the RSF, reportedly saying “Algunade is as far as can be from the RSF.”

We were unable to contact the RSF, despite repeated attempts, and letters to Abdul Rahim Hamdan Daglo delivered via Al Gunade have not been answered.

Taken together, the spreadsheet, the corporate registry documents and the reports of court proceedings lead us to the opinion that Al Gunade is owned and controlled by the senior leadership team of the Rapid Support Forces.

The source of the money

The RSF spreadsheet is mainly concerned with setting out how 148m AED (US $40m) was spent. To us it feels like a draft spreadsheet put together for internal use, accounting for a particular tranche of funds received. The spreadsheet also lists ‘cash inflow’ of 150m AED (US$41m) – describing it as ‘Deposit from technical support’ (ايداع من الدعم الفني ). The incoming funds arrived in the first half of 2019 – three dates are mentioned in April and May.

The leaked bank documents showing financial transactions between Tradive and the RSF analysed by Global Witness also showed payments during roughly the same period, albeit of different amounts. It is unclear whether the two sets of payments listed in the spreadsheet and, separately, in the bank documents are related.

Can you help? Remaining questions: One of the remaining challenges is to determine the origin of the money listed in the spreadsheet. Could it have come from a state sponsor — for example as payment for the provision of RSF mercenaries to Yemen’s war? Could it have been related to gold sales, or other commercial activities?

The people behind the RSF financial network

The RSF spreadsheet contains a number of names which can be identified, as well as a few which we have been unable to identify so far.

Mohamed Hashim “Koko”

Source: Mohamed Hashim Koko (left) at Algoney’s wedding, Facebook, October 2017

An individual mentioned in the RSF spreadsheet is Mohamed Hashim ‘Koko’, pictured here with Algoney Hamdan Daglo at Algoney’s wedding. A ‘Mohamed Hashem Hmad’ is also mentioned on an earlier version of the GSK website, alongside Algoney Hamdan Daglo, as joint CEO and founder of GSK Advance.

For example, one line states: “Petty cash for Mohamed Hashim Koko travel to China for the purposes of RSF equivalent to 2000 dollars”. Another linementions he “purchase[d] 10 laptops for RSF members for a training course in Abu Dhabi - by Koko”. He is also listed as delivering US$33,000 to Algoney – with reference in the spreadsheet to ‘Rwanda’ and debt to ‘A’.

Koko used the GSK logo as his profile picture on his Facebook page in December 2017, indicating an affiliation with the company (saved copy available on request).

When we sent out requests for comment to the companies in the spreadsheet one company replied to say that a “Mohamed Hashim” was the individual who placed the order, and that payment was received from Tradive General Trading, the organisation owned by Algoney Hamdan Daglo. We believe that it is likely that this Mohamed Hashim is Koko.

Mohamed Hashim Koko did not reply to repeated attempts to contact him for comment, either directly or via GSK.

Khabab Mirghani

Source: Picture of Khabab Mirghani with Algoney (rear) on trip to India. Facebook, August 2017

The RSF also paid Khabab Mirghani for a variety of tasks including petty cash for trips to China and Germany, an item listed as “transfer for the military card” and purchasing plugs and power switches. (See the full spreadsheet for these transactions.)

Khabab Mirghani failed to respond to a request for comment.

Saddah Hassan a Sudanese man living in Dubai, is listed numerous times in the RSF spreadsheet, making payments to others, buying phones, and in particular buying car parts and organising shipping. On Google Maps Saddah can be found ‘checking in’ to companies named in the spreadsheet.

Sadah Hassan failed to respond to a request for comment.

Mohamed Abdallah Aljack

Another individual named in the spreadsheet – in connection with a transfer to an entity in Russia – is "Wed AlJack" (Wed in a Sudanese accent means son of AlJack). Global Witness believes this is a reference to Mohamed (nicknamed Mody) Abdallah Aljack whose Facebook page shows he works for GSK. An earlier version of the GSK website shows a “Mohamed Algack” in a list of staff.

Mohamed Abdallah Aljack failed to respond to a request for comment.

In conclusion

In this piece, we’ve aimed to ‘show our workings’: how we corroborated the leaked financial documents with shipping records, corporate documents, social media research, internet infrastructure analysis, geolocation techniques, and analysis of dozens of RSF videos to examine the vehicles used by the militia.

Through these methods, we’ve been able to show in our briefing how Hemedti and the RSF have captured a huge swathe of the country’s gold industry, how they use apparent front companies and banks based in Sudan and the UAE, and how their procurement network works. This is important as the RSF are alleged to have been responsible for human rights violations, including the June 3rd massacre.

Now, over to you…

So far, we haven’t been able to identify every payment, every recipient or every vehicle. We’ve published the RSF spreadsheet in Arabic and English in the hope that others might take up the challenge of further investigating the financial networks behind the RSF. Please contact us to let us know how you get on.

You can contact us on twitter at @MohAboelgheit @RichyK37 @nickpdonovan