Minerals underpin our daily lives, from the cars and smartphones that we use to the infrastructure and architecture that surrounds us. They have driven the economic development of many countries and could drive that of many more. Yet, often mined and traded in insecure, poverty-stricken and unregulated areas, they may instead enrich an unscrupulous few.

Getting access to reliable data on mineral extraction and trade is challenging. This can be down to issues of physical access (for example in Myanmar or DRC), an unwillingness on the part of companies and governments to be more transparent or a lack of technical capacity of providers. This lack of information makes investigating business practices and exposing wrongdoing more difficult.

The importance of satellite imagery

This is where satellite imagery comes in. Data generated from satellites, and, in some cases drones, could provide citizens, researchers and journalists unprecedented access to surface markers of mining activity. This data could be used to verify official statistics and flag discrepancies, or as proxies where no other statistics exist, and thus be an important tool for holding the mining sector to account

If used responsibly, companies could also employ satellite imagery to help identify risks in their supply chains (such as discrepancies between the location of mines and export statistics to look out for cross-border smuggling) and governments to monitor otherwise hard to access regions.

Here at Global Witness we’ve manually reviewed high-resolution satellite imagery to get the investigative insights we need, for example when looking at ISIS talc mining in Afghanistan and logging in Papua New Guinea. But this often requires advance knowledge of what you are looking for and, perhaps more importantly, a lot of time – practical when the area is small, but less so over a larger region.

The role of artificial intelligence

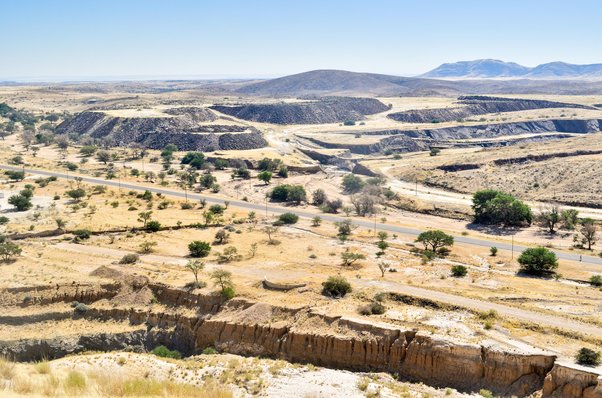

Eastern DRC’s dense forests and tropical cloud cover could have hampered the resolution of the Landsat satellite imagery. Cloudy Landsat 8 satellite image overlaid on a high resolution map. Paradiso Mine (an artisanal gold mining site), Ituri Province.

Developments in artificial intelligence and machine learning may provide a solution to the challenges of using satellite imagery. Computer algorithms can now be trained to look for specific markers in images that are either too subtle for a human to identify or would take too long for them to see.

In other domains, these approaches are already improving our lives. Scientists have developed programmes that are better at detecting disease in retinal scans than doctors, and publicly available satellite imagery is already being used by environmental watchdogs to detect and estimate forest cover loss.

Last year Global Witness joined DataKind and NRGI to explore the feasibility of using satellite imagery and artificial intelligence to automatically detect certain types of mining activity across a large area. To our knowledge this kind of project has never successfully been done before.

We set out to build a computer programme capable of automatically identifying the location of mines using satellite imagery. For this first attempt, we focussed on small-scale mining in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo – for two reasons:

- Small mines are harder to find than larger industrial ones, which have more obvious and extensive markers. If we could do it with small mines, we knew we could also easily use the model/data to identify larger ones.

- We had “training data” readily available for this region and type of mine.

Training the model

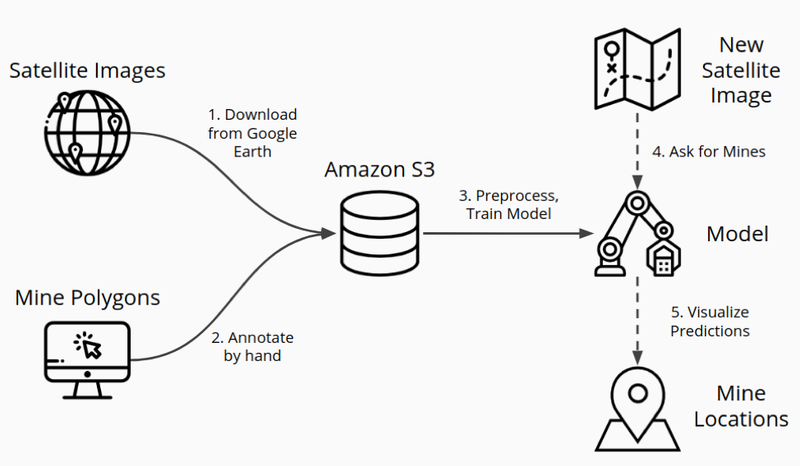

In order to build the model we used a technique called machine learning. Machine learning is a branch of artificial intelligence and has a variety of applications in everyday life, from Google Translate to email spam filtering. In statistical terms, we were seeking to predict the location of mine sites. This meant assigning a probability that a given pixel of a piece of satellite imagery was in fact part of a mine.

The first thing we needed was satellite imagery and lots of it. We needed it to be quickly accessible to the software we were going to build and we needed it to be free. Amazingly, a service called Google Earth Engine now makes historical data from the Landsat satellite available in the cloud for just this purpose. The Landsat passes over the same places on Earth every sixteen days. It’s an extraordinarily powerful tool allowing you to analyse dynamic changes in the landscape and environment that could be indicative of mining.

Second, we needed a “training” dataset with the real location of some known artisanal mines. The algorithm could then “learn” what a mine pixel looks like and more accurately predict where other mines exist. Finding a training dataset of artisanal mines in eastern DRC could have been tough, but we were lucky to have access to data collected by the International Peace Information Service (IPIS).

Our team of volunteer data scientists then built an application to outline each of the mines identified by IPIS, effectively drawing shapes around their boundaries (see below image).

A screenshot of outlines of the manually drawn IPIS mine sites that were used to train the model

These shapes – which represented known mine sites – could then be fed into our machine learning algorithm to train the model. The volunteers found that so-called “random forest” algorithms (nothing to do with actual forests!) were the most effective at predicting mine sites.

The model’s effectiveness was evaluated by seeing how many of the known (but “unseen”) mine sites from the IPIS dataset it was capable of accurately identifying whilst only being trained on a partial portion of the data. The idea being that the better it could identify these mine sites, the better it would be able to identify entirely new or previously unidentified mine sites.

The results were promising. The best model could identify 79.7% of the known mines. The downside – and where more work is required – is that the model had a high false positive rate. This meant that it often identified pixels as mines where no mining activity was present. Of all the pixels that were not part of known mine sites, the model could only identify 48.4% of them correctly.

What's next?

While the model needs some refinement, it has clearly shown that this is a fruitful avenue for further research.

As with all technology, it has its limitations and could be captured for private or commercial advantage, or be misused, and thus help perpetuate certain current, irresponsible trading models.

To mitigate these risks, we believe that open source development – the process of making computer code and its outputs freely available to all – is a critical exercise for accountability organisations like ours. It creates information infrastructures that serve the public interest and produce knowledge that can be used by everyone.

The alternative is that technological innovation takes place within proprietary walled gardens. Proprietary systems can reinforce the information asymmetries where certain powerful actors – whether governments, companies or individuals – supress information, which they themselves use to their advantage.

We are seeking to work with technologists in DRC and elsewhere to refine and investigate applications of the programmes we have produced. If this is you, please get in touch here: [email protected].

DataKind have open sourced all the code produced and we hope that this can kickstart innovation for social good in this area. For developers, civic hackers and academics interested in building on the model we created, the source code is available on Github here.

Shout outs

A special thanks goes to DataKind and the volunteers who worked on this project:

- Krishna Bhogaonker, University of California, Los Angeles

- Daniel Duckworth, Google Brain

- Junchuan Fan, University of Maryland, College Park

- Sina Kashuk, DataKind

- Ryan Vilim, Sidewalk Labs

- Katie Yoshida, Foursquare