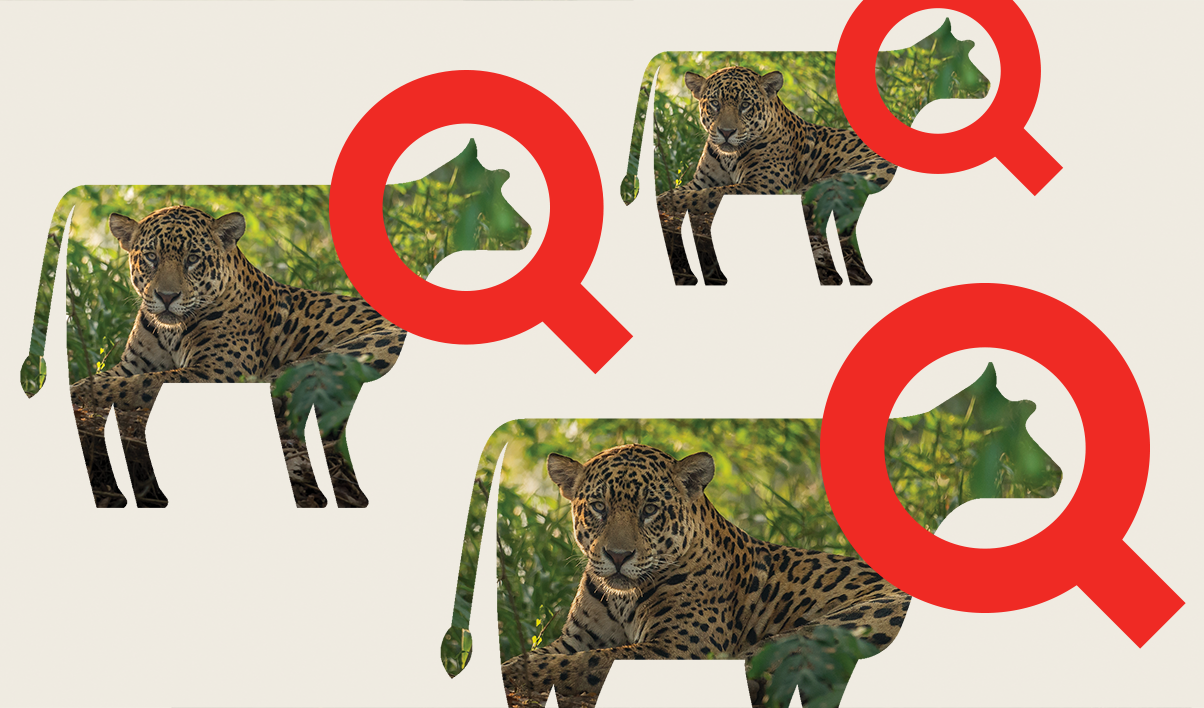

Jaguars vs cows: The biodiversity crisis under JBS’s shadow

The jaguar's future looks increasingly uncertain as Big Agribusiness tears down its home in Brazil's tropical forests to make way for cattle ranching

Trending investigations

-

Sunk costs: A mega-airport in the path of climate disaster

Flights from one of the world’s largest airport projects may be grounded within 30 years due to the risk of sinking land and rising sea levels. 27 January 2025

-

Slash and sell

A Canadian asset manager part run by green finance champion Mark Carney cleared thousands of football fields worth of tropical forest in Brazil, our investigation can reveal. 08 November 2022

-

How the militarisation of mining threatens Indigenous defenders in the Philippines

With skyrocketing global demand for critical minerals – vital to the green energy transition – Indigenous groups and biodiversity are at risk in the Philippines. 03 December 2024

Climate crisis in focus

-

The critical minerals scramble: How the race for resources is fuelling conflict and inequality

While Trump zeroes in on embattled Ukraine's critical mineral reserves, conflict and inequality clash with efforts for a just energy transition across the globe

-

How can we hold companies responsible for the damage they cause?

Irresponsible companies are causing environmental destruction and human rights abuses around the world – but there is action we can take to stop them

-

What is climate disinformation?

Climate disinformation is hindering our ability to combat the gravest threat of our time

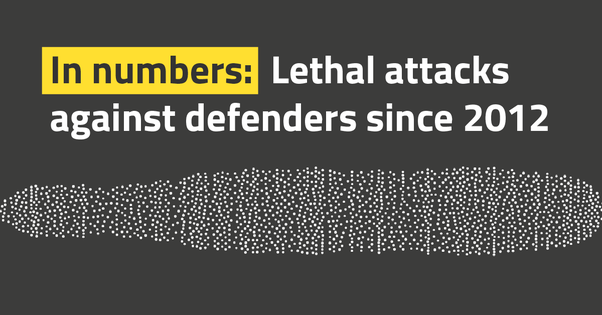

Defending our planet's frontline

Latest articles

Taxing polluters for a fairer, greener society: Joint civil society policy platform

Tax Justice UK, Oxfam GB and Global Witness outline a suite of evidence-based policies the UK government could take to ensure those most responsible for climate breakdown pay their fair share and raise billions of vital revenue

Jaguars vs cows: The biodiversity crisis under JBS’s shadow

The jaguar's future looks increasingly uncertain as Big Agribusiness tears down its home in Brazil's tropical forests to make way for cattle ranching

The time for change is now

The climate crisis is no longer an event on the horizon. It’s here, it’s now. Learn how you can support fearless investigative campaigning to expose the industries fuelling climate breakdown.

About us

Global Witness is an investigative, campaigning organisation that challenges the power of climate-wrecking companies, and stands with the people fighting back