The EU is signing Strategic Partnerships with mineral-rich countries to secure a supply of transition minerals. But are its green ambitions clouding its judgement?

What do you get if you take an authoritarian regime, a government accused of disregarding the rights of Indigenous Peoples, and throw in a few countries with a history of corruption and human rights violations? It's the strategic partners of the EU.

Last week the EU signed a Strategic Partnership on critical minerals with Serbia.

This latest deal is shrouded in controversy. Mining expansion in Serbia – a country rich in lithium deposits – has been met with local opposition. In 2022, the government revoked lithium mining licenses after being accused of ignoring the project’s potential for environmental harm.

Since then, after legal action from mining group Rio Tinto’s Serbian subsidiary, a Serbian court ruling has overturned the decision to revoke the license, causing widespread dismay from environmental activists.

The new partnership with Serbia for a resource that locals have said no to exploiting is the latest in a long line of controversial deals that the EU is signing to secure its share of transition minerals.

What are Strategic Partnerships?

When the EU set out its Critical Raw Materials Act earlier this year, it placed Strategic Partnerships and trade deals right at the heart of it.

The bloc’s ambition to be climate neutral by 2050 is heavily dependent on its drive for the electrification of transport and low emissions technologies.

But critics have questioned its pursuit of a resource-intensive growth strategy that doesn’t address the overconsumption of natural resources by wealthy countries as the root cause of climate change.

The EU has been signing Strategic Partnerships since 2021. These deals with resource-rich countries are intended to secure the EU’s access to a reliable supply of minerals critical to the energy transition.

Serbia joins a list of 13 other countries that have signed Strategic Partnerships and Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with the EU: Argentina, Australia, Canada, Chile, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Greenland, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Namibia, Norway, Rwanda, Ukraine and Zambia.

Questionable bedfellows with chequered pasts

There is an urgent need for the EU to centre social, environmental and governance concerns in its minerals diplomacy.

The line-up of signed partnerships, however, shows a worrying trend of overlooking a country's track record in mining in favour of access to its mineral streams.

Let’s take a brief look at the lowlights of some of the serial offenders:

Rwanda: Historic links to conflict minerals

Rwanda's mining sector, particularly in tantalum, tungsten and tin, has been marred by associations with conflict minerals brought over the border from neighbouring DRC.

According to a report commissioned by the DRC government earlier this year, the extraction of these minerals helps to fund armed groups and perpetuate violence in the region.

By partnering with Rwanda, the EU risks being complicit unless stringent safeguards and transparent supply chains are enforced to prevent the exacerbation of conflict and human suffering.

Australia: Disregarding Indigenous Peoples rights

Australia's mining industry has a troubled history concerning the rights of Indigenous Peoples. Numerous mining projects have proceeded without the consent of Indigenous Peoples’ communities, leading to cultural and environmental destruction.

Cases like the destruction of the Juukan Gorge caves by Rio Tinto highlight the profound impact of mining on Indigenous heritage sites.

The EU’s partnership with Australia for minerals like lithium and rare earths must address these injustices head-on and ensure that Indigenous Peoples’ rights are respected and protected in all mining regions.

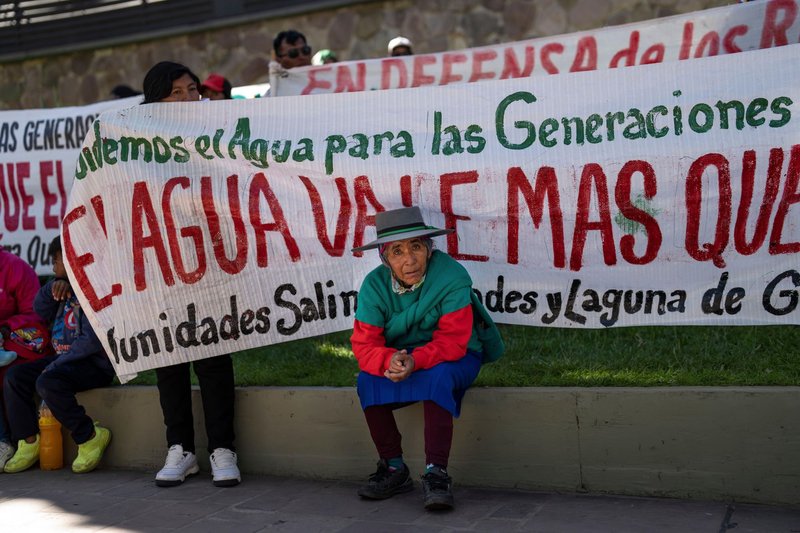

Argentina: Gross environmental harms and overuse of water

Argentina's lithium mining industry has been criticised for causing severe environmental degradation and excessive water usage.

Lithium extraction, particularly in the salt flats of the Puna region, consumes vast amounts of water, jeopardising the water supply for local communities and ecosystems.

This is particularly concerning in a region already prone to droughts and water scarcity. The environmental toll includes soil degradation, habitat destruction and potential contamination of water resources.

The EU’s engagement with Argentina needs to prioritise responsible mining practices that mitigate environmental harm, consulting with and ensuring the wellbeing of affected communities.

Uzbekistan: Authoritarian rule and oppressive practices

Uzbekistan's partnership with the EU raises significant ethical concerns due to its authoritarian government. The country is known for its repressive political regime, lack of free elections and severe restrictions on freedom of speech and assembly.

Mining operations in such an environment often lack transparency and accountability.

The EU’s engagement with Uzbekistan for mineral resources like uranium and copper could indirectly support and legitimise these oppressive practices, undermining the EU's commitment to human rights and democratic values.

DRC: Endemic corruption

Mineral extraction in DRC has been rife with corruption in the past, but the rush for transition minerals seems to be opening up a new frontier.

Recently, reporting by OCCRP found that the Manono lithium deposit appears to have generated as much as US$28 million for shell companies held by middlemen implicated in previous corruption scandals with connections to ex-President Joseph Kabila.

If the EU wants to source minerals responsibly from DRC, it will need to implement strict supply chain due diligence practices and work hand-in-hand with the DRC government to crack down on corrupt practices.

Time to place people and planet before growth?

The EU must ensure that these trade deals are not simply reinforcing a global hegemony where richer countries pilfer the natural resources of mineral-rich but economically poorer countries, leaving human rights abuses and environmental damage in its wake.

The bloc's pursuit of critical minerals is driven by the need to support net-zero technologies and reduce dependency on external powers. While important, this does not reduce the need to address the social, environmental and governance implications of its partnerships.

Ensuring that these deals do not perpetuate human rights abuses or environmental destruction is crucial for maintaining the EU's ethical standards and global credibility, and ultimately to make sure that the energy transition is fair and sustainable.

To do this, the EU needs to think very carefully about the countries it is striking deals with.

The Roadmaps – where the EU will lay out their vision for how these minerals will be extracted – should outline how the increase in mining activities will avoid causing unnecessary social and environmental harms.

It is critical that these documents are available to be scrutinised by communities and civil society to uphold the most responsible standards.