Climate disinformation is slipping through the gaps in tech companies' content moderation policies, helping to fan the flames of climate denial.

For policymakers and tech companies steeped in the challenge of preventing online harms (from child safety to financial fraud), climate disinformation often doesn’t make the cut. It falls mostly outside the scope of legislation, such as the EU Digital Services Act and the UK’s Online Safety Act, and receives less attention in tech platforms’ content policies than other forms of harm.

After all, isn’t climate conversation just online debate and reasonable disagreement? Science contains inherent uncertainties, and discussing policy trade-offs involves value judgements that can’t be fact-checked. This means that climate disinformation is often easier for companies not to tackle, rather than be accused of censoring free speech.

But climate disinformation isn’t just people disagreeing about the concept of net zero. Rather, it is a whole ecosystem that covertly undermines action on the climate crisis.

This disordered ecosystem includes pseudoscience, junk news, propaganda, misrepresented data, inauthentic behaviour, the stoking of division and hate, campaigns to undermine and discredit climate defenders, and conspiracies.

This increases the political cost of climate action and political cover for inaction. This is an especial risk in 2024, when elections across the world will determine the future of climate action, and environmental issues are already a divisive issue across constituencies.

It also enables climate doubts, fears or uncertainty to be leveraged for other more unscrupulous ends.

We don’t only see citizens engaging in bona fide debates about climate online. Powerful political and economic actors exploit the possibilities of online communication for their own benefit to promote a particular social or political agenda, for financial gain or to escape accountability.

Our climate conversation should be driven by the public interest, not vested interests.

How Global Witness is responding

In this crucial year, Global Witness has established a new Climate Disinformation Unit. Supported by the Swedish Postcode Lottery Foundation, the Unit will pilot investigations into how disinformation is used to undermine climate action by powerful actors, and how tech companies enable and incentivise this.

This work is part of Global Witness’ commitment to tackling digital threats that undermine our collective ability to act on the climate emergency.

Our aim is to identify and disrupt the systems that allow climate disinformation to be impactful and profitable.

Tackling climate disinformation does not mean shutting down democratic debate. It means the opposite: people able to discuss the realities of the climate crisis and climate policies without distortion; those affected free to speak out without fear of persecution, harassment or reprisal; those contributing to the climate crisis held to account; and institutions better able to grapple with the challenge of the climate emergency.

Dzmitry Kliapitski / Alamy Stock Photo

Case Study: The Epoch Times promotes climate denial

Our first investigation, published earlier this month, found that The Epoch Times, a conservative media outlet with a history of promoting conspiracy theories, was targeting people in the UK with adverts on Facebook and Instagram that deny the existence of climate change and question its severity.

These adverts included false claims that "Arctic ice is not melting" and that "higher CO2 levels are not a problem," and were shown to Meta platform users more than a million times.

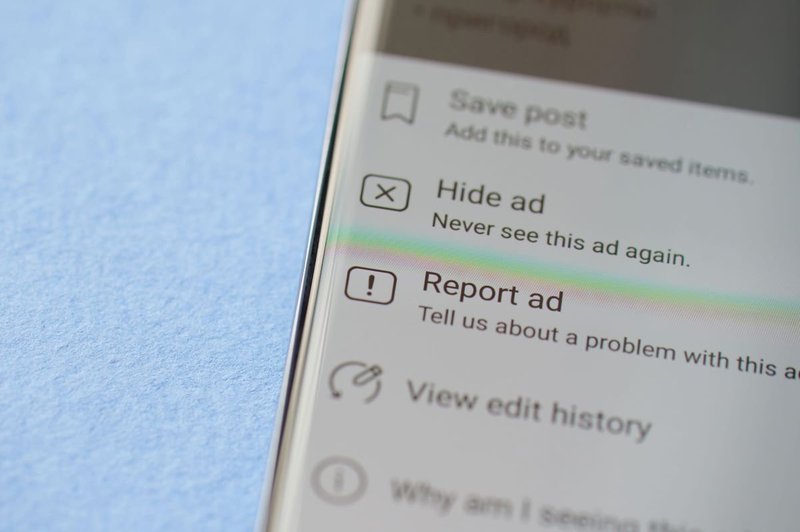

As a result of our investigation, Meta blocked Epoch Times London’s ability to post adverts for repeatedly violating their ads policies.

We are glad that Meta responded so quickly and took this step to reduce the Epoch Times’ ability to profit from climate disinformation – particularly in a UK election year. However, this investigation highlights fundamental flaws in Meta’s ad review processes.

Gaps in Meta’s processes for identifying violating content

Meta’s ad policies or community standards do not prohibit climate disinformation per se. However, if (as for other forms of misinformation) that content has been debunked by Meta’s independent fact-checking partners, it is prohibited in ads.

One of the ads we investigated linked to an article that has been debunked. The Epoch Times article claiming that Arctic ice is not melting, a claim quoted in the ad text, was debunked by Climate Feedback in March 2024.

Climate Feedback is part of Science Feedback, one of Facebook’s third-party fact-checkers since 2019. However, Meta still allowed versions of this ad to continue to run into April.

No content moderation system is, or could be expected to be, perfect. However, The Epoch Times was already banned from advertising by Facebook in the US. The Epoch Times London page should have been detected as related to The Epoch Times, given that the adverts directed users to the Epoch Times website.

Identifying climate disinformation is not a priority

Although Epoch Times London was banned from advertising on Meta following our investigation, this was for repeated violation of its ads policies, rather than because climate disinformation per se is not permitted. For climate disinformation content to be prohibited in ads, that content must have been specifically fact-checked by a Meta partner fact-checker.

In organic posts, misinformation that does not threaten imminent harm or political processes directly is not prohibited on Meta. Instead, Meta policy says viral content is fact-checked, labelled and its distribution reduced if it is false.

The problem is that not every single piece of content can be fact-checked and climate does not appear to be a fact-checking priority. It is not on Meta’s list of issues that fact-checkers should prioritise, nor is it mentioned as a category where Meta uses keyword detection to proactively group content for fact-checkers to review.

This threatens to become a vicious cycle. In an ecosystem where mitigations depend on content having been fact-checked by official Meta partners, if climate content is not prioritised for fact-checking review, it is less likely to be checked, and so less likely to be prohibited in ads.

This could mean that when users see climate disinformation it is less likely to be labelled as such, and so users may be less aware themselves to flag similar content for review.

This, in turn, would make climate disinformation less likely again to be selected for fact-checking review – not because of any deliberate permissiveness for this kind of content, but simply because it has not been prioritised within a constrained system.

How tech companies can crack down on climate disinformation

Meta could address these challenges by:

- Investing more resources in fact-checking to tackle resource constraints around prioritising climate disinformation

- Incorporating signals from International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) signatory fact-checkers, outside of Meta’s official partners, into how content is surfaced for review and labelled

- Adding the climate crisis to the list of issues that fact-checkers should prioritise

- Adding the climate crisis to the list of categories that Meta uses to group content for fact-checkers

- Publishing metrics on the efficacy of their systems and processes for enforcing their policies on climate disinformation

We are also calling on tech companies to disrupt the ways in which climate disinformation (in its many guises beyond straightforward climate denial) can be used on their services for profit – in particular through monetisation or advertising.

Companies that are acting as the custodians of our communication and information spaces – and profiting massively along the way – need to develop more concerted responses to climate disinformation and prevent bad actors from exploiting our online information ecosystems.

For more information on the work of the Climate Disinformation Unit, or to discuss potential collaborations, please contact Ellen Judson or Guy Porter.