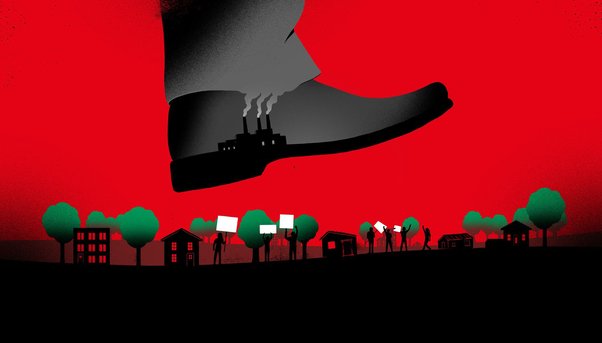

In Brazil, Indigenous Peoples are at the centre of a dispute threatening their land and human rights, as well as the fight to save our planet. A series of anti-indigenous bills have been proposed in the Brazilian Congress that pose huge risks to the environment and constitute a systematic attack on Indigenous rights.

Brazil’s Indigenous peoples are under severe pressure. They have protested against their traditional lands being burned, deforested by ranchers, and invaded by illegal gold miners. And now, they are also facing legislative threats such as Bill 490/2007. If it becomes law, many claim it would cause irreversible damage to the Amazon rainforest.

This Bill could open Indigenous lands to economic exploitation and make the process of land titling even more challenging. This could enable continued exploration of illegal gold mining sites, as well as encouraging new extractive activities without prior and informed consultation with affected communities, in some cases forcing contact with isolated Indigenous peoples.

This new assault on Indigenous land rights comes in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected their communities, according to The Coalition of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil - APIB. At the same time, the pandemic has been used as a smokescreen by some sectors in Brazil to push laws that will limit indigenous peoples’ rights and create an even more hostile environment for them. Some even warn of a genocide against Indigenous peoples.

Boosting the power of Big Agribusiness

This Bill also threatens to increase the power of Brazil’s already influential agribusiness lobby. These companies are now more powerful than ever and have been helped by the Bolsonaro administration in gaining access to protected lands, and eroding the legal rights of Indigenous communities to their territory.

Brazil’s largest parliamentary group, the Frente Parlamentar da Agropecuária, which represents powerful agricultural and livestock businesses, has provided political support for Bolsonaro’s agenda to open up lands and resources, previously safeguarded from exploitation.

The consequences of this political agenda for the environment are stark. In the first two years of Bolsonaro's government, deforestation rose 48% in protected areas. In 2020, the Brazilian Amazon suffered the highest levels of deforestation in the last 12 years, with over 1 million hectares disappearing - an area almost ten times the size of London.

During the first six months of 2021, forest clearance in the Amazon is already 17% higher than the same period last year. Comprehensive studies now show the Amazon has become a carbon source rather than a sink due to forest loss.

“Our History does not start in 1988”

A total of 505 Indigenous lands have been identified, covering 11.6% of Brazil’s territory. There are 305 different peoples, most of whom live in the Amazon region and speak 274 languages, with many more living in isolation. To understand more about the current situation, we spoke with two Brazilian activists.

Marcia Wayna Kambeba is a writer, speaker for indigenous and environmental issues and poet from the indigenous Omágua/Kambeba community, currently living in the Pará state. She has a MA degree in Geography, a PhD in Linguistics, and is also the first indigenous woman to serve in the public municipality of Belém as an Ombudsman.

My fight started when I was seven years old inside the Tikuna’s communities with my grandmother. This fight against activities such as land grabbing, gold mining is not new. When these companies (or illegal activities) invade our territory they have a huge impact not only on the land but also in our culture. [With this Bill] I fear a process of extermination and desertification in the Amazon, and that future generations cannot enjoy the same resources

Zahy Guajajara is an indigenous woman, artist and activist from the Tentehar community, widely known as Guajajara, and is currently based in the UK. She considers this moment with a sense of urgency.

It is not only Brazil but the world that needs to understand that the act of preserving nature is not only an obligation of indigenous peoples, it’s an obligation for the world. With forests standing, people will also be standing. When indigenous peoples decide to go to Brasília [to protest] despite the pandemic and the present situation it is due to something much more dangerous than COVID-19 and its variants: this government

Despite the pandemic, representatives of Indigenous peoples went to the capital, Brasília, in June during the Rise of the Earth camp to protest against Bills such as 490/2007. They are fighting for their very survival, and even facing police brutality while doing so.

Eroding Indigenous Peoples’ land rights

Bolsonaro’s administration is one of the worst, since 1985 in terms of titling indigenous lands. In two and a half years, no indigenous territories have been formally recognised by the government.

Both the former and the current president interrupted this process by using a legal procedure that incorporates the “Marco Temporal”, also known as the ‘Time Limit Trick’, in which indigenous peoples would only have the right to lands they were residing in as of the 5th of October 1988, the date that the most recent Brazilian Constitution was signed. Alternatively, if they were not occupying the customary lands they claim as theirs, they would have to prove their ownership in court or in a material conflict.

This legal thesis, defended by the agribusiness sector, is being used by proponents of Bill 490/2007. The arbitrary 1988 time limit restricts indigenous rights by neglecting their history, and ignoring the expulsions, evictions, forced migrations and violence they faced prior to that date. It also ignores the fact that until 1988 Indigenous peoples were considered as dependent on the state (tutelado) and couldn’t independently access justice to fight for their rights.

If approved, Bill 490/2007 represents an imminent threat by targeting Indigenous peoples’ fundamental rights. For this reason, many of Brazil’s indigenous people are now fighting to keep the forests standing and to have their rights secured, in acknowledgment that their history didn't start in 1988. And their fight certainly does not stop here. They are the guardians of our culture and our forests, which play a singular role in regulating the climate and in the protection of livelihoods for generations to come.

2022 update

Since the publication of this blog, many other attacks on the rights of Indigenous peoples and on the environment have taken place at the hands of President Bolsonaro’s government and its allies.

In March 2022, for example, one chamber of Brazil’s congress fast-tracked a law proposal aimed at authorising mining and hydroelectric dam construction on Indigenous lands, including in areas with isolated communities. The justification for this was that the Russian invasion of Ukraine would make fertilisers more expensive, requiring the opening up of new areas to extract potassium, a key ingredient in its production.

That statement was contradicted by research from the well-respected Federal University of Minas Gerais. It pointed out that none of the potassium deposits are located on Indigenous land, and that two thirds of these lie outside the Amazon, far away from almost all of Brazil’s Indigenous areas.

In an open letter, a group in the Brazilian congress which acts to protect Indigenous peoples’ rights denounced the bill, claiming it was part of a “package of destruction”, arguing that it was unconstitutional, and also that it disregards international human rights treaties.