Widespread confusion over AI around the US election is the result of a poorly regulated tech sector

Douglas Rissing / Getty

In 2023, an audio deepfake of a politician talking about rigging the Slovakian election went viral. Many people saw this as the start of a new era of digital deception, with AI-generated content on course to disrupt elections around the globe.

Now in the last quarter of this "Year of Elections", without a doubt, AI has changed the information landscape. But its effects haven’t been as straightforward as people predicted.

For sure, AI-generated information has proliferated, from bot farms spreading AI-generated propaganda, to political parties using AI in their campaigns.

In the US, the public remain concerned that AI will be used to produce false information in election campaigns. But AI-generated disinformation hasn’t yet had significant impacts on manipulating or changing election results.

But while AI-generated content may not have overwhelmed our access to reliable information so far, the phrase "AI-generated" increasingly sows confusion and distrust in our democratic discourse.

Don’t like the claims someone is making? It’s far easier to claim that the evidence they have is AI-generated than to actually have to create competing evidence yourself

As with "fake news" before it, claiming something is AI-generated is now a go-to tactic to attack political opponents.

Don’t like the claims someone is making? It’s far easier to claim that the evidence they have is AI-generated than to actually have to create competing evidence yourself.

In the midst of public uncertainty about AI and rapid tech advancement, it is increasingly easy to use the idea that AI manipulation could have occurred in order to muddy the waters.

This has been particularly evident around the US election campaigns. In online discussions around the campaigns, real images are being described as AI-generated, AI images are being misattributed, and images are being manipulated to appear to be AI-generated.

For instance, Kamala Harris has been frequently accused of using AI to make the crowds at her rallies seem larger.

Social media users have claimed that genuine images of crowds must have been AI-generated. In another case, a parody rally image which was actually AI-generated was shared, and falsely attributed to the Harris campaign.

And these haven’t just been fringe social media rumours: Donald Trump amplified one such claim, calling for Harris to be disqualified from the election for creating fake images.

An old tactic of propagandists is not just to spread highly convincing false content, but to confuse

Similarly, a genuine photo of Donald Trump raising his fist in the air after an assassination attempt against him was edited to add extra fingers to his hand.

The edited photo was then shared as if it were the original, and the apparent extra fingers used as evidence that the image was AI-generated and hadn’t really happened.

Apparent missing fingers in a photo of "Walz’s for Trump" led to accusations that the photo was AI-generated, but a higher-res version of the photo showed many of the "missing fingers" actually present.

The Trump campaign was also accused of using AI-generated clips of Kamala Harris in a campaign ad, which in fact were genuine clips from two different speeches used next to each other.

Meanwhile basic image editing and genuine images shared with misleading captions continue to spread online.

No wonder that 29% of voters are unsure whether they have seen AI-generated content around the election on social media.

This widespread confusion is a result of unfettered tech development, where new technological tools and services have been developed in traditional Silicon Valley fashion: innovate first, deploy them for profit and think about risks later.

This plays into the hands of bad actors trying to deliberately stoke division and advance their own agendas.

An old tactic of propagandists is not just to spread highly convincing false content, but to confuse things enough that people lose the ability to navigate or distinguish fact from fiction.

And that strategy of distortion and deception is made much easier when new ways of creating and manipulating information burst onto the market without sufficient public understanding or transparency.

Imagine that generative AI tools were designed to make clear to their users what generative AI was

Imagine that major companies had prioritised collaborating to mitigate these kinds of risks instead of being the first to release a shiny new product.

Imagine that generative AI tools were designed to make clear to their users what generative AI was and how it worked. That safeguards were rigorously tested, instead of reportedly having to be added in after harm has occurred.

Or that companies, as the default, worked with civil society and regulators in advance to establish shared approaches to problems like how to identify or moderate AI content.

In a world where the introduction of generative AI was slower, clearer and, dare I say, more boring, there would have been less chaos and confusion to exploit.

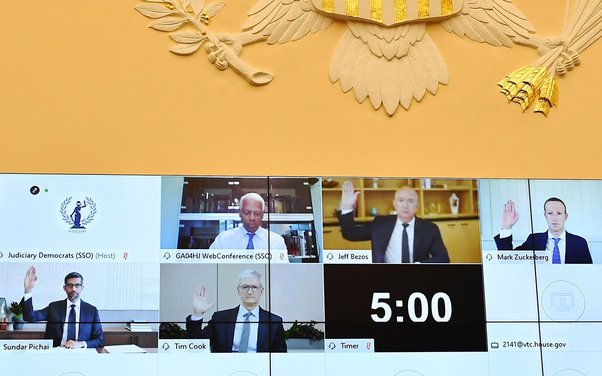

In the age of social media-mediated news consumption, we need greater upstream oversight of how tech giants are acting on information risks.

There are ongoing efforts to bring in more upstream regulation, such as requiring more thorough risk assessments of AI technologies.

However, the EU AI Act won’t be fully enforced until 2026, while the UK and US are still working out what their regulatory response to AI risk, if any, will be.

In the meantime, it looks like we’re in for a few more years of AI information generating chaos.