For over a decade, the trade in conflict minerals has fueled human rights abuses and promoted insecurity in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

The Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, passed by the US Congress in July 2010, includes a provision – section 1502 – aimed at stopping the national army and rebel groups in the DRC from illegally using profits from the minerals trade to fund their fight.

Section 1502 is a disclosure requirement that calls on companies to determine whether their products contain conflict minerals – by carrying out supply chain due diligence – and to report this to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

This legislation has the potential to make a significant positive impact on the ground in the DRC; however, there has been considerable fear-mongering and spreading of misinformation about the Act’s requirements and likely impact.

This document seeks to clarify some of the most common misconceptions.

Dodd Frank 1502 does not place a de facto embargo on minerals from the DRC

Dodd Frank 1502 is a disclosure requirement only and places no ban or penalty on the use of conflict minerals. If companies discover they have been sourcing conflict minerals from DRC or adjoining countries, it is not illegal for them to continue doing so; however, they must report this to the SEC.

Critics of the law are arguing that whatever the law’s intentions, 1502 will in practice bring an end to the trade in minerals mined in the east of Congo.

It is true that mineral exports from the region have dropped significantly in recent months. The downturn stems from a six month suspension of mining and trading activities imposed by the Congolese government and an overly restrictive interpretation of Dodd Frank by industry associations.

This has forced many artisanal miners to seek alternative livelihoods and has had serious implications for miners and their families.

The idea that the current hiatus represents a permanent shut-down of the minerals trade in eastern DRC is misplaced, however. Indeed, despite alarmist talk of an end to eastern Congo’s minerals sector, the past few months have seen major international companies unveiling plans to invest in and source from mines in areas of Congo covered by the law.

For example, NYSE-listed Motorola Solutions Inc has recently invested in mines in the southern Province of Katanga and a TSXV-listed Canadian company has acquired a 70 percent interest in a South Kivu tin mine.

Amidst the claims of some international observers that the law is a disaster for Congo, it is worth noting that the Congolese government has publicly expressed its support for Dodd Frank 1502 in a letter to the SEC and that the measure is also backed by mining sector officials in the eastern areas of the country that are most directly affected. Congolese civil society groups have also welcomed the law, most recently in a press release from the Bureau of Study, Observation and Coordination of the Regional Development of Walikale (BEDEWA). As the Governor of North Kivu province said to Global Witness researchers in April this year: the war has been going on since 1996, why didn’t the US government pass this law ten years ago?

Implementation of the law should not be delayed; companies have had ample time to prepare

The problem that has come to be known as ‘conflict minerals’ has been widely documented for over a decade now and businesses have long been aware of the harmful impact their purchases can have.

Despite having many years to put the necessary control measures in place, most companies did not begin even paying lip service to changing their practices until the threat of a US law materialised two years ago.

The sad reality is that the majority of businesses will not live up to their responsibilities until legally compelled to do so.

A delay in the implementation of the law in effect buys extra time for those armed groups responsible for horrendous attacks against civilians in Congo to further benefit from the minerals trade.

The conflict minerals problem overlays long-standing regional disputes relating to political disenfranchisement, ethnicity and land. Wide ranging reforms are needed to ensure that Congo’s natural resource wealth benefits the country’s population, but tackling the trade in conflict minerals should be a priority.

This trade substantially exacerbates existing sources of conflict and blocks efforts to break the cycle of violence in the eastern Kivu Provinces, where human rights abuses, including gender-based violence such as rape and sexual slavery, have reached catastrophic proportions.

The UN Joint Human Rights Office in the DRC reported that over 300 civilians were raped by armed groups in an incident that took place in August 2010, in three villages located close to mining sites in North Kivu province.

The UN investigation revealed a direct link between the violence and competition over access to minerals. In June this year, several people were killed in the same region during fighting between two armed groups that were contesting a lucrative mining site.

It is well understood that many companies, in the first year of the law’s implementation, may not be able to say if they are sourcing from DRC or adjoining countries.

However, through full compliance with the law, companies can lay a foundation for following years and improve on their supply chain due diligence and the data they are able to generate.

Here it is worth recalling, once more, that there is no penalty if companies cannot determine whether the minerals they use come from DRC or neighbouring countries. The consequence for businesses that find themselves in this situation is that they have to submit to the SEC a ‘conflict minerals report’.

Delays to the implementation of the law may also deter and even undermine companies that have begun making efforts to improve their supply chain controls, for example via the industry-driven Conflict Free Smelter programme.

This concern is voiced in a letter to the SEC in June this year from a major international smelter of tantalum: “We urge the SEC to issue the final regulation for Section 1502 as soon as possible so that industry has certainty regarding the implementation process, and so that companies that currently source conflict minerals do not enjoy a competitive advantage.”

Dodd Frank 1502 targets abusive units of the Congolese army as much as it does militias

A recent New York Times article argued that Dodd Frank 1502 is no longer relevant because the militias or rebels it was designed to target have now joined the government army.

This assertion is completely misplaced. Dodd Frank 1502 targets units of the Congolese army as much as it does militias precisely because the army is comprised of large numbers of ex-rebels.

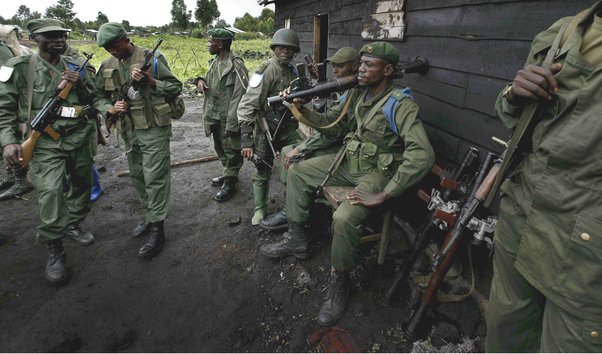

The Congolese army is a major player in the conflict minerals trade and some battalions are known to regularly commit appalling crimes against the civilian population.

Furthermore, militia groups do still control and benefit from minerals in certain areas of eastern Congo. The notorious FDLR rebels continue to derive significant profit from the trade in gold, and a recent violent clash between two other armed groups in North Kivu’s Walikale territory was partly motivated by competition over a newly discovered tin ore deposit.

It is possible for manufacturing companies to identify which mineral smelter produced the metal they use

Section 1502 requires that companies take steps to determine if the minerals in their products originate from DRC or adjoining countries. To know with any degree of certainty the origin of the minerals they use, companies must first find out who their processors or smelters are.

Global Witness is recommending to the SEC that all companies be required to

- identify and, importantly, publish their smelters;

- verify the smelter’s chain of custody documents; and

- watch out for ‘red flags’ which may indicate the minerals come from DRC and adjoining countries.

Some companies have stated that this process is too costly and difficult to undertake. However, Global Witness field researchers have been able to track supply chains into DRC and neighbouring countries, with significantly less resources and funds than are available to multi-national corporations.

To establish these tracking and reporting systems companies can pool their resources and work together to comply with the legislation.

Weak infrastructure and institutions in DRC speaks to the need for more stringent country of origin requirements, rather than more lenient ones.

Since these systems are currently under development, more effort will be needed initially to ensure that the information disclosed is accurate and reliable.

There are actually only a handful of smelters globally that deal with tin, tantalum and tungsten. According to the Information Technology Industry Council (ITIC) there are less than 20 major tantalum processors, and research done by Global Witness indicates that there are fewer than 20 major tin smelters and less than 15 major tungsten smelters

In February, Apple released its “2011 Supplier Responsibility Report” in which the firm details how it traces its supply chain, first to the suppliers that create the subcomponents to their products and then to the smelters that processed the ores. Intel has already conducted “on-site reviews on 11 tantalum smelters in six different countries” as part of the Conflict Free Smelter programme.

The SEC should lay down a common, internationally recognised standard for supply chain due diligence that applies to all four minerals covered by the law

Although there is some variance amongst supply chains across the mineral categories, they do not differ significantly enough to warrant different due diligence requirements.

In the 2010 report, Do No Harm, Global Witness maps out the route, from mine to manufacturer, along which minerals travel to demonstrate that the supply chain is not as complex as some corporations would have it seem.

A clear due diligence standard is necessary in order to provide accurate, consistent and reliable information in the reports companies submit to the SEC. If issuers are allowed to choose from a variety of different measures, some are likely to choose the ones with the least stringent requirements.

Global Witness is recommending that the SEC, in its final rules, states unequivocally that the due diligence requirements for Section 1502 of the Dodd Frank Act are exactly the same as those already adopted by the OECD and the UN Security Council.

In July the OECD sent a letter to the SEC signed by nearly 200 companies, governments and Congolese and international NGOs which makes the same recommendation.

The due diligence standards adopted by the OECD and the UN Security Council consist of a five point framework that includes on the ground risk assessments and audits. The OECD guidance is the product of a tripartite working group comprising companies, governments and NGOs.

Read this page in