In 2013, oil giant Exxon signed a $120 million deal with the Liberian Government for an oil block it knew was tainted by corruption. As our exposé reveals, Exxon negotiated the deal despite its concern over “issues regarding US anti-corruption laws."

Download the investigation: Catch Me If You Can: Exxon’s complicity in Liberian oil sector corruption and how its Washington lobbyists fight to keep oil deals secret

Our key findings include evidence that Exxon:

- Knew its purchase might enrich former Liberian politicians who were likely behind the block

- Structured the deal in a way it hoped would bypass US anti-corruption laws

- Knew Liberia’s corrupt oil agency had previously bribed officials to approve oil deals, including the very block it wanted to buy

But this isn’t just a story about Exxon and Liberia. It’s also about how Exxon – along with others in the oil industry – has repeatedly attacked the US anti-corruption and oil transparency law that makes it possible for us to uncover deals done in this notoriously corrupt and opaque oil and gas sector.

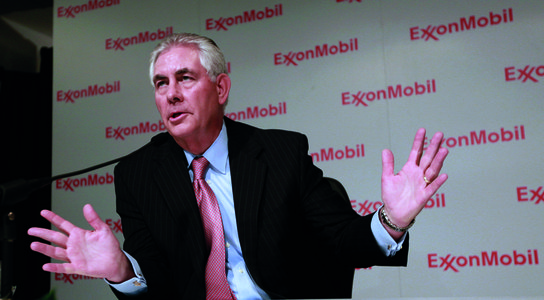

Exxon and Tillerson lobbied against anti-corruption laws

In 2010, three years before the deal exposed in our investigation, Exxon’s then-CEO, a “red-faced angry” Rex Tillerson, had jetted to Washington, DC, to fight Section 1504 of the Dodd-Frank Act in person. He aimed to make sure Section 1504 – requiring US-listed oil, gas and mining companies to report on payments they make to governments – would never see the light of day. Despite his lobbying efforts, a resolute Congress passed it into law.

In 2017, on the same day Tillerson was sworn in as Donald Trump’s first Secretary of State, the Trump administration and Congress moved to overturn the rule enforcing the law.

Exxon and its associates in the American Petroleum Institute continue to wage a war to kill Section 1504 to this day.

What Exxon knew about the Liberian oil block

Our evidence shows that Exxon suspected the company it was purchasing the oil block from – Broadway Consolidated/Peppercoast (BCP) – was likely part-owned by former Liberian politicians who had illegally granted themselves the block. Exxon knew its purchase might enrich these former politicians. The company also knew the oil block had originally been awarded to BCP after Liberia’s oil agency paid bribes.

Despite these corruption red flags, Exxon didn’t walk away from the deal. Instead, it engineered a plan to skirt US legal exposure, using the Calgary-based Canadian Overseas Petroleum as a go-between to purchase the block.

Exxon, BCP, BCP’s suspected owners, and the Liberian Government did not respond to Global Witness when asked about the deal. Canadian Overseas Petroleum did respond, stating that its due diligence showed that there were no legal problems with the deal, it had legal advice on its anti-money laundering and anti-corruption obligations, and that there was no credible evidence that BCP was owned by former officials. Details of this response can be found in Global Witness’ report.

Liberian officials received unusual payments

Exxon’s purchase in 2013 was also accompanied by over $200,000 in unusual, large payments made by the corruption-tainted Liberian oil agency to six Liberian officials who approved the deal.

Officials who received payments include Liberia’s then-Justice, Finance and Mining Ministers, each of whom received $35,000 – more than doubling their annual salaries.

The officials receiving the unusual payments and the posts they filled at the time were:

- Finance Minister Amara Konneh

- Justice Minister Christiana Tah

- Mining Minister Patrick Sendolo

- National Investment Chairman Natty Davis

- NOCAL CEO Randolph McClain

- NOCAL Board Chair Robert Sirleaf. Sirleaf, who is the son of then-President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, was reportedly working pro-bono at the time.

Three officials who received payments – Davis, Sirleaf and Tah – have stated that they were “bonuses,” authorized by NOCAL’s Board of Directors for negotiating a good deal with Exxon. Details of these responses can be found in Global Witness’ report. There is no evidence that Exxon knew about these payments, but they were likely made from the same oil agency account into which Exxon had just deposited $5 million.

Exxon, Broadway Consolidated/Peppercoast, and those who received the unusual, large payments should be investigated to determine if they broke laws in the US and Liberia.

US can prevent oil sector corruption

The US needs to make sure that corrupt oil deals are stopped by adopting a strong Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rule to implement Section 1504 of Dodd-Frank, the law Exxon and other oil majors have aggressively been lobbying against.

A strong Section 1504 implementing rule will prevent the type of corruption seen in Liberia. We were able to uncover Exxon’s complicity in the corrupt Liberian oil sector because Liberia published data about Exxon’s payments to the government – the same project-level data that Section 1504 requires.

But most countries do not publish this data, making it critical that the US require it. Without it, we may never know how far companies are prepared to go and we won’t be able to stop the corruption that keeps people poor and destabilizes countries.

If you’re in the US, please call your members of Congress today at 202-224-3121 and tell them to protect Section 1504 for oil and gas transparency.

NEW INVESTIGATION: Exxon paid $120 million to the #Liberia government for an oil block it knew was tainted by corruption. https://t.co/eUCQdgbJdu #NoSecretDeals pic.twitter.com/vQE1JmxW1k

— Global Witness (@Global_Witness) March 29, 2018

Find out more

-

Julie Anne Miranda-Brobeck

Head of US Communications and Global Partnerships