The world’s top two commodity traders used middlemen notorious for their role in Brazil’s mammoth ‘Car Wash’ bribery scandal, our investigation with Public Eye reveals.

Previously unreported court material also places Trafigura, the world’s No. 3 trader, in negotiations with a Car Wash player now so infamous he is known as the “Deacon of Bribes”.

Corporate behemoths Glencore, Vitol and Trafigura have a combined turnover of more than half a trillion dollars - greater than the GDP of Austria - and exercise enormous power over the world’s raw materials trade. Whether it is the grain in your bread, the fuel in your car or the copper wiring in your electric toaster, there is a fair chance it was handled by these commodity traders. But all three have courted controversy over corruption allegations, links to unsavoury regimes and environmental abuses. Past exposés by Global Witness and Public Eye have highlighted commodity traders’ use of corrupt intermediaries in major mining and oil deals.

Our investigation raises new questions over the probity of the top three commodity traders, in connection with their choice of intermediaries. The middlemen’s allegedly criminal role in Car Wash emerged after their dealings with the commodity traders detailed in this report.

To piece together the exposé, Global Witness trawled through hundreds of Car Wash court documents to reveal previously unreported facts and spoke with sources across Brazil.

Key findings

- Vitol’s

agent for Brazilian oil deals was a key player in a network shown in court

documents to have drawn up multiple bribery schemes, with the collaboration of insiders

at state oil firm Petrobras. Vitol paid him through an

offshore company that had been at the centre of this network’s plans.

- Glencore

struck a deal with another middleman who had been part of this same network.

Glencore made an agreement with the middleman over the purchase of a cargo of

fuel oil from Petrobras, the commodity trader admitted.

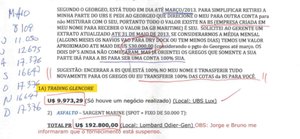

- A

Glencore subsidiary paid at least $2.1m to a father-and-son team of alleged

bribe fixers. Glencore says it engaged the pair as legitimate brokers and

denies impropriety. But a financial report prepared for a top Petrobras

director lists thousands of dollars due as a bribery payment from a “Trading

Glencore” deal, allegedly paid by the fixers.

- Trafigura

is the subject of a current police investigation in Brazil, Petrobras told

Global Witness. Trafigura and Brazil’s Federal Police declined to comment.

- Two of

the most central figures in the Car Wash scandal – including Brazil’s “Deacon

of Bribes” – exchanged messages on how to dole out bribe payments from a

proposed $2 billion Trafigura oil deal, court

documents show. Trafigura admits proposing the abortive oil deal to Petrobras,

but said it had not "retained" the

Deacon, now serving a 13-year bribery sentence.

In correspondence with Global Witness, Glencore and Vitol acknowledged doing business with the middlemen featured in our report. They denied any wrongdoing, or knowledge at the time that the middlemen were engaged in unlawful activities. But hiring professional bribe-givers and money-launderers is a major corruption red flag.

Trafigura was the only one of the three companies that would not provide a clear answer on whether it dealt with any of the middlemen. Trafigura says on its website that “transparency is indispensable in our corporate responsibility journey”. It has declared its support for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, the benchmark oil and mining anti-corruption body. This year Trafigura appointed the long-time head of the EITI as its chief spokesman.

Global Witness is calling on the UK and its overseas territories, the US and Switzerland to launch investigations into the commodity traders in Brazil, to determine whether bribes were paid to secure oil deals. These jurisdictions are home to their major trading operations, company headquarters, bank accounts and company registrations (see here for the links). Brazil’s police and the Car Wash task force – a team within the Public Prosecutor’s Office - are already investigating the intermediaries and their deals.

The ‘Deacon of Bribes’ Jorge Luz and his son Bruno. Their tentacles were in almost every corrupt deal studied by Global Witness

Those deals all came to light as part of the devastating Car Wash scandal, which subsumed the country’s economy, politicians and the state oil company Petrobras errupting in 2014. Former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has been jailed over the scandal and outgoing President Temer investigated; in all, some 20 political parties have been implicated and several of the country’s leading businessmen have been put under lock and key.

On 28th October Brazilians elected former paratrooper Jair Bolsonaro as their new president, a man who has repeatedly praised the country’s 1964-85 military dictatorship. Despite over a decade in Congress as a member of Brazil’s Progressive Party (which was heavily implicated in the Car Wash scandal), Bolsonaro stood for president on an anti-establishment ticket.

While promising to end corruption, Bolsonaro could undermine the checks and balances that restrain abuse within Brazil’s political system. He recently said that if elected he would “put an end to activism in Brazil”, and his political rivals – including those in Lula’s Workers’ Party - will have to “go overseas, or to jail”.

Car Wash – Brazil’s mega-scandal

So what was Car Wash?

In 2014, Brazilian police investigating money laundering at a bureau-de-change

attached to a petrol station uncovered a bribery racket at Petrobras. Some 28 major corporations were found to have paid

kickbacks to Petrobras directors in return for infrastructure contracts. At

least £1.4 billion was filched from the state company.

Much of the money provided back-door funds to a host of Brazilian political parties, keeping otherwise unstable governing coalitions together. Anonymously-owned companies in tax havens and foreign bank accounts helped launder the loot. One Petrobras director alone channeled €20m to banks in Monaco from accounts in the Bahamas, Panama and elsewhere. Such was the upheaval, with billions slashed in investment, that it helped bring about the worst recession in Brazil since records began, with the economy shrinking nearly 4% in 2015 and 2016.

The focus of Car Wash investigators has so far been on Petrobras’s construction deals, and its trade in oil has barely featured. Brazil is the world’s ninth largest oil producer, behind the United Arab Emirates and one place ahead of Kuwait. It has the second largest crude reserves in South America, after Venezuela. Brazil is also the world’s ninth largest economy, with 207 million people and a mushrooming number of gasoline-chugging vehicles (90 million and counting).

Brazil’s oil trade: an 'illicit framework’

Not only does Brazil produce 2.1m barrels a day of oil, but it also imports billions of dollars of fuel and “light” crude, which is needed for its refineries. This makes the country a bonanza for oil-trading companies, which handle the logistics of import and export. The figures speak for themselves. Court documents show that between 2003 to 2015 Vitol did at least $12.2 billion worth of business in Brazil and Trafigura $8.9 billion.

Global Witness’s interest in these dealings was piqued by some astonishing plea bargain statements by two of the most senior figures in Petrobras:

- Nestor

Cervero, a former International Director of Petrobras, sentenced to 32 years

under house arrest for laundering more

than a million dollars in bribes;

- and

Delcidio Amaral, a former Gas and Energy Director at Petrobras, who became the

Workers’ Party leader in the Senate—before being humiliatingly voted out of

office after his November 2015 Car Wash-related arrest.

Amaral said in his February 2016 statement that the Supply Department was “one of the most coveted areas of Petrobras, mainly because of the trade in oil abroad”. He described the daily trade in hundreds of thousands of barrels of light crude as an “illicit framework”. “Small variations in the price of oil represent high earnings for the main operators, giving rise to a terrain for various illicit activities, since prices may be artificially altered,” he continued. The trade was all done in London through “brokers”, according to Amaral.

‘Political interference’

Cervero’s plea bargain the previous month echoed these claims, raised the role of the commodity traders. He said Petrobras’s illicit business affairs concerned the trade in fuel too.

“This marketing is done mainly through the trading companies,” he said. “The biggest tradings are Glencore and Trafigura."

"The volume traded is very large and the cents of daily trades can yield millions of dollars at the end of the month in bribes.”

“There has always been some kind of political interference in the trading area,” he said. Cervero also said the trade in oil and oil products was carried out through the Supply Department, which had substantial freedom as the board of directors did not need to sign off such deals.

The Supply Department director was Paulo Roberto Costa, who became infamous in Brazil after admitting taking tens of millions of dollars in bribes in a plea bargain that turned the Car Wash investigation stratospheric. A senior Brazilian Federal Police source told Global Witness that when they raided Costa’s house, all the furniture had cavities for stashing cash. He has since been sentenced to 12 years over bribes for refinery construction deals.

Nestor Cervero detailed how manipulating oil prices could generate huge bribes. Credit: Getty Images/Evaristo Sa

Global Witness investigators went to extraordinary lengths to speak with Amaral and Cervero about their testimony. Amaral lives in the central Brazilian city of Campo Grande, where our investigators spent four days waiting for an interview that never materialised. The investigators also tracked Cervero down to a remote ranch in the Atlantic forest of Itaipava, southern Brazil, where he is under house arrest. Speaking through the intercom, he declined to answer questions beyond an acknowledgement of his testimony on Trafigura and Glencore.

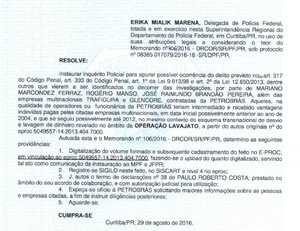

In August 2016, police launched an inquiry into Petrobras figures named in the plea bargains, along with Trafigura and Glencore, covering their activities from 2004 to 2012, according to a leaked police document. The document says police were investigating possible crimes by various named Petrobras officials and businessmen “as well as the multinational companies Trafigura and Glencore, which had contracts with Petrobras”. The public officials “seem to have intermediated and received bribes paid by the aforementioned multinational companies, possibly starting before 2004 and possibly up to 2012” in the context of Car Wash.

Glencore said it is "not aware of any investigation into Glencore relating to Brazil” and has never been contacted about any such investigation. It added: “The order appears to mention Glencore in the context of opening an investigation into the three individuals, rather than Glencore.” Federal Police would not comment on whether the two-year-old investigation was still running.

Global Witness’s new findings will heighten concerns over corruption risks, at a time when the three top commodity traders are already under scrutiny. This March, a trust for Venezuela’s state oil company sued Glencore, Vitol and Trafigura and other companies for bribery and insider trading, claiming they cheated $5.2 billion from the company by corruptly rigging oil tenders. In July, Glencore’s share price tumbled 12% in a day, over news of a US investigation into alleged money-laundering and corruption in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria and Venezuela. The commodity companies deny any wrongdoing.

The biggest oil trader of the three is Vitol.

Vitol’s payments to Swedish ‘agent’ and a suspected money-launderer

Warlords, dictators and rebels… plus a pillar of the British establishment

With a turnover of $181 billion, Vitol moves over seven million barrels of oil and petroleum products daily—enough to supply Germany, France, Italy and the UK. Under the leadership of Ian Taylor - CEO from 1995 to this year, before becoming Chairman – Vitol’s value rocketed by 3,500%.

Taylor, a donor to the UK’s Conservative Party and Chairman of the Royal Opera House, lends Vitol establishment credentials. He has burnished Vitol’s image by speaking publicly on “responsible corporate behaviour”. But the company often attracts attention for the wrong reasons, whether it’s over dealings with corrupt intermediaries in Nigeria, Congo-Brazzaville or Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, or its payments to a Serbian warlord and a billion-dollar deal with Libyan rebels.*

The company’s Brazilian deals now add to the controversies.

Agent Ljungberg: Vitol's man in Brazil was allegedly a key player in the corrupt Brasil Trade syndicate

Global Witness has discovered that Vitol and one of its subsidiaries engaged not one but two middlemen whose involvement in the Car Wash scandal is now detailed in extensive court evidence.

The first of these was Bo Ljungberg, a Swedish businessman living in Rio de Janeiro, whose smiling photograph and thumbprint feature in a dossier compiled by Brazilian Car Wash prosecutors. Ljungberg’s home was raided by Federal Police in August 2017, who seized laptops, phones and an iPad. Vitol admitted to Global Witness: “Mr Ljungberg has acted as an agent for Vitol.”

Pressed by Global Witness, it conceded it had paid Ljungberg in 2011 and 2012 “as a consultant, to support Vitol in identifying oil business opportunities in Brazil and to assist with operational aspects of the transactions”. He was paid “through a company of which he was the 100% owner, Encom Trading SA”. Vitol wouldn’t say how much he got. The commodity trader said it had conducted “the usual due diligence processes” on both Ljungberg and Encom saying they had shown up “nothing of any concern”.

“Had there been, Vitol would not have entered into the arrangement.”

USB stick… and a dynamite email cache

As we shall see, Ljungberg was part of a group alleged to have conspired in several corrupt schemes, according to court filings. Emails and documents unearthed by Brazil’s Federal Police establish Encom’s central role in Car Wash bribery schemes in forensic detail.

And it all began with a USB stick.

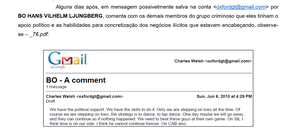

In July 2015, police in Rio arrested a retired admiral for running a huge kickback scheme over a nuclear reactor. Among the material seized from his house was a USB stick containing a dynamite cache of documents, including screenshots from a Gmail account with the address [email protected]. Eight users had access to it. No emails were actually sent from the account. Rather, users saved messages in the drafts folder for others to view—an apparent security measure. This criminal network was referred to by Brazilian police as the “Brasil Trade” group.

In August 2018, the Car Wash task force laid out a host of charges against Brasil Trade members and associates, ten people in all. They were accused of having “organised themselves… to practise crimes against the public administration, and to the detriment of Petrobras, notably corruption” from February 2010 to July 2012. Ljungberg himself – Vitol’s man in Brazil - was charged with belonging to a criminal gang, corruption and money-laundering. The case is yet to be tried, and Ljungberg - now living in Sweden - had not filed a defence by the time of publication.

His holiness, and a political fixer

At the heart of the Brazilian state’s case against the Brasil Trade syndicate was a corrupt scheme involving Petrobras’s granting of $180m of contracts for asphalt imports between 2010 and 2014. This asphalt was destined for a major road-building and infrastructure programme. The seller was giant Florida-based asphalt trader Sargeant Marine. The task force and police investigators detailed the Sargeant Marine scheme in court documents, using evidence from the seized USB stick.

The evidence sets out the corrupt practices of Ljungberg and his co-conspirators at Brasil Trade. It also illustrates the modus operandi of Encom, which received a payout from the Sargeant Marine deal and was repeatedly touted as a partner in Brasil Trade’s schemes.

Another leading

Brasil Trade member was Jorge Luz, known in Brazilian media as the Deacon of Bribes,

and his son Bruno Luz. They were jailed for more than 13 and six years

respectively for orchestrating over $20m in bribes in Petrobras deals over

oil-survey vessels (separate from the Brasil Trade

schemes). A prosecutor on the Car Wash task force told journalists “they

are perhaps the largest operators [of kickbacks] in the international area of

Petrobras” - which is saying something.

The Luzes were key to landing the Sargeant Marine deal. The oxfordgt emails show the duo using their political and Petrobras contacts to obtain confidential commercial data that helped remove Sargeant Marine’s competitor and secure the asphalt contracts. Assisted by one of Brazil’s top politicians – Workers’ Party parliamentary leader Candido Vaccarezza - and Petrobras Director of Supply Paulo Roberto Costa, Bruno Luz managed to obtain Petrobras’s commercially sensitive pricing “formula” for asphalt, according to the evidence.

Armed with this, Sargeant Marine could offer its product at just the right price to Petrobras. Meanwhile the Brasil Trade group factored in a generous cut for themselves, along with bribes for Petrobras officials and politicians whose palms needed greasing.

In an email of 7th May 2010, Ljungberg congratulated Bruno Luz on getting the formula. Bruno replied: “This is certainly the result of our efforts, I mean from all of us. We just need to be patient as I am sure we are on the right track.” In his testimony to the police, Ljungberg said he had never even heard of the Brasil Trade group. He confirmed jointly owning Encom but denied receiving any payment from the Sargeant Marine deal.

Ljungberg issued a pep talk a month later, telling his Brasil Trade colleagues they would overcome internal resistance within Petrobras. He ruminated in Hollywood style: “We have the skills to do it. Only we are stepping on toes all the time… The strategy is to dance; to tap dance.” He finished: “We need to beat these guys at their own game.”

Divvying up the loot

When the asphalt contracts were secured, Jorge and Bruno Luz received commissions in textbook money-laundering fashion, the funds paid from a Sargeant Marine subsidiary into Swiss accounts registered by anonymously owned companies in the Marshall Islands, the court documents show. The Luzes then split the cash, Bruno accounting for the funds meticulously in spreadsheets using initials and codenames. An August 2010 spreadsheet shows income from the first Sargeant Marine contract being divided up, with 40% of the funds going to the “Operation” (the Brasil Trade group), another 40% to “Coordination” (code for Vaccarezza and another lawmaker) and 20% to “Casa” (the House – the Luzes’ code for Petrobras directors, in this case referring solely to Costa). The deciphering of the code names is based on police analysis and witness testimony.

A fifth of the Brasil Trade group’s commission ($49,506) then went to “BO and CH” – Bo Ljungberg and fellow suspected conspirator Carlos Herz. Bank records show they received it in the Swiss BNP Paribas account of the anonymously-owned British Virgin Islands company Encom Trading SA, which they were co-owners of. As stated previously, Encom was also the company Vitol paid Ljungberg’s fees to, for being an “agent” and “identifying oil business opportunities”.

Ljungberg and Herz left the Brasil Trade group after the first Sargeant Marine deal in 2010, according to Bruno Luz’s deposition.

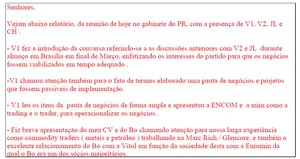

In the USB stick files, Encom can be seen angling for a range of corrupt deals. In April 2010, the “Deacon” Jorge Luz, Herz, the Brasil Trade group’s political point-man Vaccarezza and a lawmaker codenamed V1 met Costa in his office on the 23rd floor of Petrobras’s brutalist headquarters in Rio de Janeiro. Herz summarised the meeting in the oxfordgt email account, writing that V1 explained the role of Encom to Costa: V1 “elaborated a business schedule and projects that could be implemented… and presented Encom and me as the trading company and the trader, to operationalise the trades.” That same email lauded the “excellent relationship” between Ljungberg and Vitol, citing Encom’s interest in “mediating buy and sell operations with the big players”.

According to Herz’s account, Costa argued in the meeting that the commodity trading corporations already had direct contracts with Petrobras, so “he could not accept having Encom as an intermediary”. “Jorge Luz disagrees,” wrote Herz. “He trusts that if we structure business involving the traders, PRC [Paulo Roberto Costa] will endorse them.”

‘Keep Vitol warm’

At the April 2010 meeting Herz proposed several deals Encom could take a cut in. These included bunker (shipping) fuel; a fuel oil deal with Argentina involving a politically connected middleman there; Bolivian diesel; and finally oil sales to and from Brazil.

A March 2010 document in the USB stick headed “Trade Brasil” – created by Jorge Luz’s secretary, meta-data shows - relates that “V2” (codename for Vaccarezza, say prosecutors) requested to see Encom’s accounts each month. His stated ambition was to get no less than 100 million Brazilian reais ($55m at the time) in “support” from the company’s deals. The Federal Police analysis reads: “The intention to use the company Encom Trading for carrying out criminal business remains evident.” Vaccarezza denies being the real V2.

Vitol featured repeatedly in the Brasil Trade emails discovered on the USB stick.

Of the April meeting at Costa’s office, Herz wrote: “I took advantage of the occasion to mention that Vitol, through Mike [Loya – the head of Vitol’s US subsidiary Vitol Inc.] has no objection to working with us in bunkering fuel, heavy and light [crude], in brief in all sectors as long as PB [Petrobras] clearly signals that Encom is the marketing channel... We’ll have to see if we can structure trade with Vitol”.

One message written in summer 2010 (author unclear) stated: “We are already identifying some opportunities with Vitol (fuel oil)”, adding that they were dealing with a named senior Petrobras official on the matter. Another Carlos Herz message of June 2010, referring to the Argentinian proposal, said: “We have to keep Vitol warm.”

In its analysis, the Federal Police wrote: “It was the intention of the GT [email account members, aka Brasil Trade] to participate in the purchase and sale of petroleum with Petrobras using Encom as an intermediary. Jorge Luz wanted to get closer to the representatives of Vitol.”

The next email suggests a meeting between Ljungberg and Loya was arranged in Houston – where Vitol has its US headquarters - for Sunday 16th May 2010.

Loya ‘does not recall’

Questioned by Global Witness, Vitol confirmed that Loya met Ljungberg around that date, saying they were old colleagues.

Loya “does not recall the details of the conversation”, a Vitol spokeswoman said. “As head of Vitol Inc, Mr Loya would not be involved in discussions about potential product deals with Petrobras,” the spokeswoman continued. “These would be handled by the relevant product desk.”

Loya, who denies any wrongdoing, told Global Witness of Ljungberg: “In our dealings, there was never any cause for me to raise concerns.”

A fortnight after the meeting, Bruno Luz sent a message to the Brasil Trade group concerning the potential Vitol deal: “Fuel oil: BO [Ljungberg] was tasked with obtaining the minimum value with Vitol and MA [another Petrobras official] the maximum value with CAB [a senior Petrobras petroleum trade manager].”

Prosecutors said this related to the sale of fuel oil by Vitol to Petrobras. Ljungberg would find out Vitol’s minimum selling price, while the two Petrobras officials would establish Petrobras’s maximum buying price.

“In possession of such data the GT [or Brasil Trade] negotiated the commissions that would be distributed between the members of GT and other beneficiaries (Petrobras civil servants, politicians etc.),” they wrote.

A Federal Police analysis of Bruno Luz’s message said it was similar to an email between the Brasil Trade conspirators about Sargeant Marine from just a month earlier. One member of the group had written: “We have to move fast to get the maximum price from [another Petrobras conspirator] and to formulate our offer, trying to also get the maximum possible commission for Brasil Trade. I already have the minimum price for SM [Sargeant Marine].”

This suggests the Sargeant Marine deal was a blueprint for the scheme involving Vitol.

The potential for bribery and price manipulation in the proposed Vitol deal was thus extremely high. The two Petrobras officials were listed in the USB stick files as taking hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes in the Sargeant Marine affair and were among those charged in August 2018. Jorge and Bruno Luz corroborated these payments in testimony, although the Petrobras officials challenge this in their defence statements.

Vitol said there is no evidence implicating it in bribery. The company carried out due diligence on Ljungberg and Encom, a spokeswoman said.

“The use of agents is common in our industry,” she added. “Vitol is not aware of any illegal or improper behaviour in its dealings with Petrobras. Nor do the documents provided by Global Witness demonstrate this.”

A lawyer for Dan Sargeant, former president of Sargeant Marine, said: “We have no comment on these issues.” Sargeant Marine set up a new asphalt-trading company with Vitol in 2016. Mr Sargeant is its managing director.

Ljungberg claims innocence… but the Deacon spills the beans

In their police statements, Ljungberg and Herz denied any criminality, saying they had no knowledge of Encom receiving funds from the Sargeant Marine deal. They acknowledged jointly owning Encom and meeting with the Luzes to discuss potential deals, which they said never materialised.

Ljungberg said he had never used the oxfordgt account and had only seen Vaccarezza on TV. Herz admitted writing some of the emails and being present at Petrobras HQ when Vaccarezza lobbied for business. He said the deals he discussed with Brasil Trade did not go through.

The Luzes chose to collaborate with the police. They recognised their central role and explained how the bribery scheme worked, including the Brasil Trade group’s interactions with Petrobras officials and politicians. The Deacon said that Ljungberg and Herz were part of the Brasil Trade group and “received [the payment for the Sargeant Marine deal] through the offshore company Encom Trading SA”. Bruno Luz said Ljungberg did have access to the oxfordgt account.

Vaccarezza’s lawyer said he was “never an intermediary in any type of negotiation between private companies and Petrobras”, while Vaccarezza himself told police after his August 2017 arrest that he “did not get a cent from Sargeant Marine” or from the Luzes. He denied being present at the April 2010 meeting at Petrobras. Vaccarezza was charged with corruption offences, along with the other members of the Brasil Trade group, in August 2018.

Paulo Roberto Costa admitted to police that he received hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribe payments from the Sargeant Marine deal in a Lombard Odier account in Geneva.

Vitol’s payments to suspected Car Wash money-launderer

The second intermediary to have received Vitol funds was Nelson Martins Ribeiro, accused by Brazilian authorities of bribery and being a big-time money-launderer as part of the Car Wash scandal. He is under investigation by the Car Wash task force for handling bribe money relating to Odebrecht, Brazil’s engineering and construction colossus. Four Odebrecht-linked offshore companies regularly paid three Ribeiro companies registered in the Cayman Islands: Crown International, Enterprise Tech Industries and Apple Capital Corp.

Ribeiro passed payments on to Paulo Roberto Costa within a few days of the money arriving in his accounts, prosecutors said. You could see it going in and out. Between 2009 and 2012, Costa received some $5.7m in this way.

Judge Sergio Moro - who has presided over most of the Car Wash cases from his base in the southern city of Curitiba - said the evidence indicated that Ribeiro “acted as an intermediary in the payment of bribes between contractors and managers of Petrobras”. Between 2009 and 2012, more than $190m and €4.5m passed through Ribeiro’s accounts, court documents show.

‘Criminal origin’

Ribeiro was jailed for ten days and banned from leaving Brazil for almost three years, to prevent flight. His travel ban has been lifted due to the prolonged inquiry, but he is still under investigation. He has not been charged. Judge Moro, in an interim ruling, said the evidence “indicates he is a professional money launderer”. (Moro has now handed over the reins to another judge, after having controversially accepted the position of justice minister in Bolsonaro’s new government.)

He said: “By using secret accounts, under the name of offshore [companies], he seems to have concealed the nature and criminal origin of the assets in order to ensure impunity for those involved.”

Contacted via WhatsApp, Ribeiro said: “I will defend myself in court… I am sure that everything will be clarified and that my involvement will finally be perceived as non-existent.”

The court documents detailing Ribeiro’s payments also show that from February 2009 to November 2012 a whopping $8.2m paid by Cockett Marine – a marine fuels trader half-owned by Vitol – ended up in two of those Ribeiro offshore companies with accounts in the Cayman Islands: Enterprise Tech Industries and Apple Capital Corp. Some $1.3m of this was paid in 17 instalments after Vitol acquired its stake in Cockett in July 2012.

The Federal Police stated: “The transfer of resources of a large company that maintains billion dollar contracts with Petrobras directly to offshore accounts belonging to a professional money launderer seems strange.”

Vitol confirmed the payment amounts but said Cockett’s bank statements showed they went to companies called Madison Corporation and Maclaren Inc, which they said was associated with Ribeiro. This raises the possibility that Maclaren and Madison forwarded the money on to the other Ribeiro companies.

Vitol denied any impropriety. A local Cockett manager merely engaged a company associated with Ribeiro “to obtain local currency to fund operations”, Vitol said, adding: “Neither Mr Ribeiro nor any of his associated companies ever acted as an intermediary or representative of Cockett in respect of generating new business with Petrobras or other clients.”

Vitol says it undertook due diligence before buying half of Cockett Marine and only became aware of the payments in 2015. A spokeswoman said: “Vitol understands that a Cockett entity was named in connection with the Lava Jato [Car Wash] matter in 2015; that Cockett cooperated fully with Brazilian authorities, that no proceedings for bribery were brought and the matter is now considered closed. Vitol has a zero tolerance policy in respect of bribery and corruption.”

Cockett Marine’s chief executive Cem Halil Saral said: “Kindly note that neither Cockett nor any Cockett employee has been charged.”

Glencore: payments to suspected bribe middlemen

Walking in the footsteps of the ‘King of Oil’

Vitol’s biggest rival is Glencore, which from its base in the quiet Swiss town of Zug runs a corporate empire with a $205 billion turnover and a global web of mining and oil interests. It was founded in 1974 by the “King of Oil” Marc Rich, who is credited with revolutionising the trade of crude but earned notoriety after US authorities accused him of sanctions-busting in Iran and fraud. He ended up fleeing America for a Swiss exile.

Glencore is now the 11th largest company on the London Stock Exchange but the company is finding it hard to clean up its reputation.

The US is already investigating Glencore's questionable dealings in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Like Vitol, Glencore also paid middlemen now deeply implicated in the Car Wash scandal. Global Witness has uncovered that Glencore struck a deal with another member of the Brasil Trade syndicate: Luiz Eduardo Andrade, Ledu to his friends.

Glencore also made over 600 payments to a company called Seaview Shipbroking, to broker marine fuel trades. The father-and-son duo running Seaview were behind a highly lucrative system of bribes and insider information to land shipping contracts for other clients, according to a document trail presented by prosecutors.

Ledu: middleman in Glencore oil deal

Luiz Eduardo Andrade was another one of the ten people featuring in the charge sheet over the Sargeant Marine affair. Andrade – a former trader under Marc Rich - was both Sargeant Marine’s Brazilian representative and a member of the Brasil Trade group. He has been charged with corruption, money-laundering and belonging to a criminal gang. Andrade had not filed a defence by the time of publication.

Emails from Andrade speak volumes. They show him tearing his hair out as the Brasil Trade group tries to corruptly obtain the all-important pricing “formula”. He wrote that “the key” to getting the formula was with PR (Petrobras’s Paulo Roberto Costa) and Brasil Trade’s political allies.

His glee at getting the coveted algorithm is evident in a message of 7th May 2010. “Good work,” he writes. “Friends, this is a gift from the Gods!!!”

Glencore admitted doing business with ‘Ledu’, whose mugshot features in this Brazilian police document

Andrade received payouts from the Sargeant Marine deal, alongside Costa and other Petrobras officials. The Deacon of Bribes Jorge Luz and his son paid just under $292,000 to Andrade’s accounts in the US and Switzerland, the court records show. Andrade passed on $168,000 to a senior Petrobras official who helped Sargeant Marine close its deals.

The court evidence places Andrade at the heart of the Sargeant Marine deal and its dodgy payments. But Global Witness was intrigued by passing references in the Brasil Trade messages regarding Glencore, for example this from December 2010: “Glencore: Subject brought by Luis [sic] Eduardo, ex-Glencore and friend of [a named Glencore representative]. Has not been doing business for 1 year and wants to change interlocutor.”

Contacted by Global Witness, Glencore said: “Our internal review has identified an agreement with Mr Luis Eduardo Loureiro Andrade relating to the purchase of a fuel oil cargo from Petrobras International Finance Co in 2011.” Andrade has not responded to questions.

Given the evidence for Andrade’s involvement in Brasil Trade’s bribery, Global Witness believes there are grounds for investigating whether he made corrupt payments relating to the Glencore fuel oil deal.

Glencore said it “is committed to upholding good, ethical business practices”.

But, like Vitol, the company did not only deal with one middleman subsequently fingered by the Brazilian authorities.

Playing battleships

Between 2010 and 2014, Glencore’s wholly owned subsidiary Ocean Connect Marine made 121 payments totalling net $2.1m to Konstantinos and Georgios Kotronakis, another father-and-son team who feature heavily in Car Wash. Konstantinos Kotronakis, then a Greek honorary consul to Brazil, has been under criminal investigation since at least 2017 over a gigantic bribery scheme involving shipping companies that transported oil for Petrobras. The Brazilian authorities have not charged him or his son.

Court documents requesting search warrants and temporary arrests detail how this

audacious scheme worked. At its centre was, once again, Petrobras Director of

Supply Paulo Roberto Costa (he of the hollow furniture). The court documents

detail how, in return for hundreds of thousands of dollars, Costa passed

insider information to Konstantinos Kotronakis and son on where Petrobras would

need fuel tankers next. Armed with this knowledge, the five (mostly Greek)

companies could “allocate ships in strategic positions, thus allowing competitive

advantages in the face of other ship owners”, police investigators said. This

kickback was equivalent to about 3% of the contracts, initially split 40% to

Costa, 20% to Konstantinos Kotronakis, and the remainder going to other

parties, Costa admitted in his plea bargain.

Kickbacks from the shipping scheme were allegedly fuelled to the PP political party

The sums at stake were staggering. Over a five-year period, almost $900m of contracts were signed between the shipping companies and Petrobras. Between 2009 and 2013, the Greek shipping firm Tsakos alone entered into $786m worth of contracts with Petrobras, according to the state oil company’s records. Meanwhile Tsakos and its agent paid $2.4m to offshore accounts belonging to a pair of companies – Seaview Shipbroking, controlled by the Kotronakises, and GB Maritime, set up jointly by Georgios Kotronakis and Costa’s son-in-law, Humberto Mesquita. Those same companies made regular payments amounting to nearly a million dollars to Costa’s Swiss and Luxembourg accounts. Costa himself admitted that all or most of this was expressly for the inside information. The Kotronakises were involved in the “systematic payments of bribes and money-laundering”, Brazil’s Car Wash task force concluded in a court submission.

Court evidence indicates a cut went to the Progressive Party - a centre-right party - for awarding Costa his position. Amid the USB stick files are messages between none other than the Deacon of Bribes and his son, discussing the PP’s involvement in the deals.

“The kickbacks to the PP,” the task force wrote, “are even more objectionable [than bribes to Petrobras officials], as they imply undue interference in the rules of the democratic game.”

A lawyer for the Kotronakises said that, although Konstantinos Kotronakis is under investigation, "no prosecuting or criminal action has taken place by the Brazilian authorities". Georgios Kotronakis is not under investigation, he added.

In his police confession Paulo Roberto Costa admitted receiving payment from the Kotronakises into his Luxembourg account with Swiss bank UBS, for passing on inside information from 2010 or 2011. Costa’s son-in-law Humberto Mesquita, who helped manage the payments, gave a similar account to the police, describing how he and the Kotronakises set up offshore companies and accounts to channel the payments. Mesquita said he “understood that it was wrong for Paulo to participate in this”.

Tsakos made no comment.

Prosecutor: bribes were ‘modus operandi’ for Glencore’s ship-broker

The alleged criminal workings of the Kotronakises thus set out, we come to the $2.1m sent by Glencore’s subsidiary Ocean Connect Marine to the Kotronakis firm Seaview Shipbroking. This company was registered in the Marshall Islands in January 2010 - just ten months before the payments began. In February 2011, Georgios Kotronakis visited the 20th floor of Petrobras’s headquarters, where the guestbook records that he was representing Ocean Connect Marine.

Glencore told Global Witness that it had effected more than five times as many trades with the Kotronakises as the court documents list. The company said it “entered into around 600 transactions with Petrobras where Seaview Shipbroking Ltd, an independent marine fuels broking company, were engaged”. Seaview was on a panel of brokers approved by Petrobras to market the sale of bunker fuel at Brazilian ports and “assist Petrobras in securing bunkers for Petrobras’ tanker fleet at ports outside Brazil”.

While Glencore insists that the Kotronakises had a strong business record, with major companies as clients, their history is still an enigma. The Baltic Exchange in London – a leading organisation for the shipping trade - confirmed neither of the Kotronakises, nor their companies, have ever been members. This is unusual for any shipping company with a UK registered office, like Seaview.

Their record is clearer when it comes to iffy payments. Court papers show the Kotronakises paid well over $1.5m to Costa and other Car Wash players from their UBS Luxembourg account: Costa himself; another alleged money-launderer through accounts in Panama and the US; and “criminal” payments to a further Petrobras manager in charge of ship chartering and contracts. The alleged money-launderer and Petrobras manager are under investigation, a spokesman for the Car Wash task force said.

Glencore denied bribery, saying it was not aware the Kotronakises “in fact paid bribes or that OCM [Ocean Connect Marine] payments were used to fund such bribes (much less if they were paid)”. Neither Glencore nor its affiliates knew the Kotronakises “even may have been paying” bribes, a spokesman added.

“Neither your letters nor the documents you attached present credible evidence that a Glencore-related entity knowingly made corrupt payments, either directly or indirectly.”

But there is more. Soon after Costa’s arrest in March 2014, Federal Police seized a document known as the ‘Beto Report’ in a raid. This had been prepared by Costa’s son-in-law Mesquita so the Petrobras kingpin could keep track of bribes coming in left, right and centre. Under the heading “Trading Glencore”, the amount of $9,973 is listed, with an indication the money would be paid into Costa’s account with UBS in Luxembourg. Costa himself said that “the company Trading Glencore was contracted by Petrobras”, adding he “cannot remember what specific contract this payment was made for, but he is certain it is a bribe”.

Mesquita said in his own plea bargain that the sum related to a shipping contract arranged by Georgios Kotronakis. He said Georgios closed the deal “without Paulo’s help” but decided to pay Costa nevertheless.

Police raided Paulo Roberto Costa's office in this building, in Rio de Janeiro

Prosecutors on the Car Wash task force said the payment “demonstrates that, in Glencore’s contracts brokered by Konstantinos Kotronakis and Georgios Kotronakis, the payment of bribes to Petrobras employees was a modus operandi”.

Reviewing the evidence on Glencore in the round, the prosecutors added that the “probability was high” that Ocean Connect Marine’s payments also may have been used, at least in part, “to corrupt Paulo Roberto Costa and other public officers of the state-owned company”.

No charges have been brought against Glencore or any of its representatives in the Car Wash investigation.Trafigura and the ‘Deacon of Bribes’

Glencore’s rebellious child

In the late 1970s Claude Dauphin, a French metal trader in his mid-twenties, joined the upstart company Marc Rich AG – the original incarnation of Glencore - as their country manager in Bolivia. He quickly rose up the ranks, becoming a top lieutenant, and sticking by Rich as he fled US court charges in 1983 and ended up on the FBI’s Most Wanted Fugitives list.

But after power struggles at the helm of the company Dauphin resigned in 1992, taking others with him to found Trafigura. Profits were around $30m a year until 2000, but, like Glencore and Vitol, the Geneva-based company has ballooned since then. 2017 profits were at an eye-watering $2.2 billion.

Trafigura has something else in common with its rivals: its seemingly unavoidable courting of scandal. The most well-known episode is the 2006 dumping of more than half a million litres of toxic waste in open-air landfills in Ivory Coast, West Africa.

Public Eye has also published investigations revealing Trafigura’s close business ties to a top aide to Angola’s notoriously corrupt former president, and how its African petrol stations sell fuel with sulphur levels hundreds of times European standards. This was technically legal, due to lax national standards, but it caused respiratory disease and premature death, Public Eye said.

Car Wash court documents now also raise questions over Trafigura in Brazil, specifically the role played by middlemen in Trafigura's relationship with Petrobras.

To justify the “preventive detention” of the Brasil Trade group middlemen last year, the Federal Police filed a dossier of their most startling evidence. It included documents authored by the Deacon and his son Bruno, updating Paulo Roberto Costa on negotiations in 2009, where bribery is intrinsic to the deal.

‘Proposal from Trafigura’

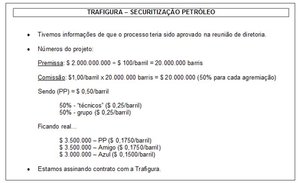

The Luzes were plotting to take a cut of Petrobras’s estimated $36.4m per day petroleum trade, the evidences shows—and that they were planning a $2 billion oil contract with Trafigura as a means to do so.

Internal divisions within Petrobras stymied the deal. But the apparent Luz-Trafigura negotiations were fairly advanced before they flopped—the Luzes said they had already submitted their own services’ contract to Trafigura and were desperately trying to seal the deal.

The plan was for an “oil-backed loan”, under which Trafigura would lend Petrobras funds to be repaid through a discount on future oil sales, said an insider with knowledge of these events.

Despite Costa’s strong backing of the deal, other Petrobras officials opposed it.

“Why should we go to a commodity trading [company] to raise money?” the source said, speaking on condition of anonymity. The proposal from Trafigura risked being “a very expensive transaction from the point of view of Petrobras”. The source’s explanation is consistent with the messages in the court document.

The Luz documents also give a breakdown of how illicit revenues from the loan would be shared, with a cut for the Progressive Party, congressional allies of the Workers’ Party. The sale of 20 million barrels of oil would generate $2 billion, of which 1% would be a “commission”, the Luzes’ euphemistic term for bribes. Of this, $10m was earmarked for the PP and those representing its interests.

But one of the Luzes’ missives – typically written by Bruno, Jorge not knowing how to use a computer - reveals that the scheme ran into trouble at a Petrobras board meeting.

“There was a lot of criticism from the finance department,” reads the January 2009 brief. “We also learnt the technical wing of the Supply [Department] is not in favour.”

The Supply Department’s experts gave a presentation at the meeting that “only points to disadvantages”, wrote the Luzes, saying: “Our worry is that deadline for approval will be extended and that the proposal from Trafigura expires.”

“We have already submitted to Trafigura the contract that will guarantee us,” said the Luz message.

Widening the net

The Luzes said they “strongly believed” that opposition had come from “Gabrielli himself”, referring to Sergio Gabrielli, then president of Petrobras. But after the deal fell through, the Luzes didn’t give up. They said in a later message that they were “working with Trafigura” on another proposal.

Global Witness approached Gabrielli at a pro-Lula rally in São Paulo, to be told he could only discuss these matters “in ten years”.

Global Witness sent detailed questions to the Progressive Party but received no reply. The party said in 2017 it has had “no connection with illicit conduct”. When the investigation against Vaccarezza was launched in 2017, the Workers’ Party told the press it “does not have any information about this case.”

Regarding the evidence discussing its proposal for an oil-backed loan, Trafigura said: “Contracts for commodity pre-payments with producers are not uncommon. A proposal for such a transaction was made by Trafigura to Petrobras.”

“But the proposal,” Trafigura said, “did not result in an agreement being negotiated or concluded. Jorge and Bruno Luz are well-known political lobbyists in Brazil. These individuals were not retained by Trafigura in relation to such pre-payment proposal to Petrobras.”

The company noted that it was “not privy to the exchanges within ‘Brasil Trade’”, and that the information in the court documents “remains ambiguous commentary and conjecture”.

Asked whether the Luzes lobbied on its behalf, and if they were promised a success fee instead of being “retained”, Trafigura failed to clarify further.

Global Witness submitted several freedom of information requests to Petrobras for the loan proposal from Trafigura and the presentation by dissenting Supply Department experts. Petrobras refused the requests, saying: “It is known to Petrobras that Trafigura is being investigated by the Federal Police, in a Criminal Inquiry that is being carried out in secrecy, and it is certain that any provision of data related to this company may disrupt the investigations in progress.”

Police and prosecutors would neither confirm nor deny that Trafigura was under investigation. Trafigura also declined to comment on whether it was under investigation.

Trafigura board member arrested

Although the loan scheme came to nothing, it is beyond doubt that a former Trafigura board member – in charge of business development in Brazil and Angola – was a prolific payer of bribes. Mariano Ferraz was sentenced to more than ten years in March 2018. He had paid Costa $868,450 for securing a tanking and docking contract for another company of which he was director, Decal do Brasil.

Although Ferraz’s bribery conviction did not relate to Trafigura, his arrest was an embarrassing episode for the company, showing criminal behaviour by one of the company’s most senior international figures. His case attracted attention from a parliamentary inquiry into Car Wash. The inquiry noted Ferraz’s importance to the firm, saying he had “risen quickly in the hierarchy of Trafigura by being able to guarantee contracts in Angola”.

When Ferraz was first arrested in 2016, Trafigura said it was “not a party to the contract between Petrobras and Decal do Brasil and does not have a business relationship with Decal do Brasil”.

‘Maturing fruits of a tree’

Asked about the allegations against Trafigura and Glencore, Deltan Dallagnol, head of the Car Wash task force, said these “are two lines of investigation that we are still developing”.

He continued: “We could compare this to the maturing process of fruits of a tree. Each fruit has a different moment in which it’s going to mature and be ready to be collected. And Car Wash is a huge investigation.”

“We are only 20 prosecutors facing more than 450 lawyers who lodge petitions on a daily basis.”

A country's natural resources revenues should be used in the best interest of its citizens, and if the giants of world trade are bringing shady intermediaries into their lucrative crude oil deals, something is going badly wrong.

Global Witness is calling on law enforcement in the UK, US and Switzerland to launch investigations into the commodity traders’ dealings during the Car Wash scandal, building on the efforts of the Brazilian authorities. The US investigation announced this year into Glencore has shown that a light can be shone into even the darkest corners of the international commodities market. And in Brazil, where the Car Wash scandal has led to unprecedented political and economic turmoil, clarity over the role of these little known giants is urgent.

*Since this report was published Vitol contacted Global Witness to say that it: denied any alleged dealings with companies in Nigeria identified as corrupt; that its 2011 oil deal with Libya was undertaken with the full knowledge of all relevant authorities; that a claim against it and others by the PDVSA US Litigation Trust has been declared unconstitutional by the National Assembly of Venezuela; and a judge in Florida, in a 5th November interim ruling, said the trust did not have standing to bring a claim against Vitol, recommending the case be dismissed.

REVEALED: Global oil traders 🏢 @Glencore and #Vitol paid millions of dollars 💰 to the same middlemen now charged with bribing @Petrobras officials in #Brazil ➡️ Find out more https://t.co/PhlOz2qHyz pic.twitter.com/EF8xv4PeZQ

— Global Witness (@Global_Witness) November 9, 2018

Global Witness believes there is a clear bribery risk in the cases of all three commodity traders. There is an inherent bribery risk involved when employing middlemen in oil deals; when they appear to have a track-record of bribery, this is even more the case. Commodity companies have featured in several legal cases and corruption scandals because of their dealings with fixers. The most recent example is a US Department of Justice investigation into Glencore’s use of intermediaries in three countries: the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria and Venezuela. The investigation relates to corruption and money-laundering, Glencore has said. Global Witness has combed through hundreds of court filings and wrung key admissions from all three commodity companies about their Brazilian dealings. While there is no smoking gun, the evidence that links the commodity firms’ middlemen to bribery, buttressed by the plea agreements from former top Petrobras officials, provide overwhelming reason for authorities to investigate further. Much of the evidence available to date comes from the side of the middlemen, against whom the Brazilian prosecutors have brought charges. Authorities in the UK, the US and Switzerland should demand the commodity firms disclose what they knew of their fixers’ behavior, and how they managed to secure valuable oil deals in Brazil. Authorities must therefore investigate whether the middlemen paid or promised bribes to secure business for Glencore, Vitol or Trafigura—and, if so, whether the multinationals were aware. For each of the commodity houses there are a number of red flags, as detailed in the report. The commodity traders have a choice to do business with middlemen. Multinationals that can readily call upon the expertise of in-country executives and lawyers to conclude oil deals would appear to have no need of the services of intermediaries.

Find out more

You might also like

-

Press release Global Witness reveals Brazil's Car Wash corruption scandal may have cost the country eight times more than the £1.4 billion stolen

As Netflix launches a major new drama based on the Car Wash scandal in Brazil, we reveal the cost to the country may be eight times higher than the eye-watering sums actually stolen

-

Campaign Oil, gas and mining transparency

Corruption and fraud in the oil, gas and mining industries props up brutal regimes and lines the pockets of kleptocrats. Companies and governments must end the secrecy and bring deals and profits into the open

-

Campaign Corruption and money laundering

Ill-gotten gains don’t disappear by themselves. Dictators, warlords and other criminals need ways to hide their identity and move dirty cash around the world.