Introduction

DRC: How a due diligence scheme appears to launder conflict minerals

Minerals extracted by hand from the African Great Lakes region are in huge demand. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Rwanda produce nearly half the world’s coltan, the main ore of tantalum, as well as large amounts of tin and tungsten ores – collectively known as 3T minerals. The metals obtained from the smelted 3T minerals are widely used in electronic equipment such as mobile phones, computers and automotive and aeronautical systems.

Regional map of Central Africa

But the Congolese army and rival armed groups that dispute power over parts of eastern DRC have for decades viewed control of mines and the minerals trade as a vital source of income. Along with the lack of effective governance in DRC and neighbouring countries, this has led the trade of minerals from DRC being linked to violent conflict and serious human rights abuses.

In an attempt to improve the sector’s governance, the regions’ governments, the UN, the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in consultation with industry and civil society, drew up new guidelines and procedures over a decade ago.

As part of this effort, industry interests set up traceability systems which, working alongside government validation of mines, were intended to establish a supply of “conflict-free”, responsibly sourced minerals.

In this report, Global Witness brings together evidence of how the most widely used of these schemes appears to facilitate the laundering of minerals originating from mines controlled by abusive militias or that use child labour.

Furthermore, the scheme many international companies are relying on to source responsibly, is also used to launder huge amounts of minerals that have been smuggled and trafficked, new evidence suggests.

Our report is based on field research in over 10 mining areas in DRC’s North and South Kivu provinces, interviews with over 90 individuals from governments, industry, civil society and academia and dozens of videos recorded by local researchers, which Global Witness has reviewed.

The results of this work corroborated research findings conducted by other credible organisations such as the UN and the Belgian research institute International Peace Information Service (IPIS).

The ITSCI Laundromat

ITSCI

In 2009 the International Tin Association (ITA), with the subsequent participation of the Tantalum-Niobium International Study Center (TIC), set up the International Tin Supply Chain Initiative (ITSCI).

ITSCI aims to provide a reliable chain of custody of minerals that are not linked to child labour or the influence of armed groups or the army.

In DRC, this means that minerals must originate from mines validated by the government as free from these associations. In Rwanda, where armed groups are not known to be active, it means among other things that minerals have not been smuggled from DRC.

In both countries, government agents acting on ITSCI’s behalf seal and tag bags of legitimate minerals before they are transported for processing or export. In 2018, the OECD evaluated ITSCI’s standard as fully aligned with its own due diligence guidance on mineral supply chains. However, our investigation reveals that the reality on the ground looks very different.

ITSCI tag sealing a bag of 3T minerals. UNGoE

Laundering of minerals from unvalidated mines in DRC

Our findings suggest that ITSCI's system has permitted the laundering of tainted minerals in DRC. Large amounts of minerals from unvalidated mines, including ones with militia involvement or that use child labour, enter the ITSCI supply chain and are exported, evidence suggests.

ITSCI’s incident reporting frequently appears to downplay or ignore incidents that seriously compromise its supply chain.

The most extensive evidence of the scheme’s failure in DRC comes from the area around Nzibira, where a trading centre in South Kivu accounted for around 10% of minerals tagged in the province in 2020. In the first quarter of 2021, the production of the validated mines in Nzibira sector amounted to less than 20% of the nearly 83 tonnes of 3T minerals tagged there.

Interviews with officials, traders, miners and others confirmed that the bulk of minerals tagged came from unvalidated mines in neighbouring territories, including mines occupied by militias and one where children frequently work.

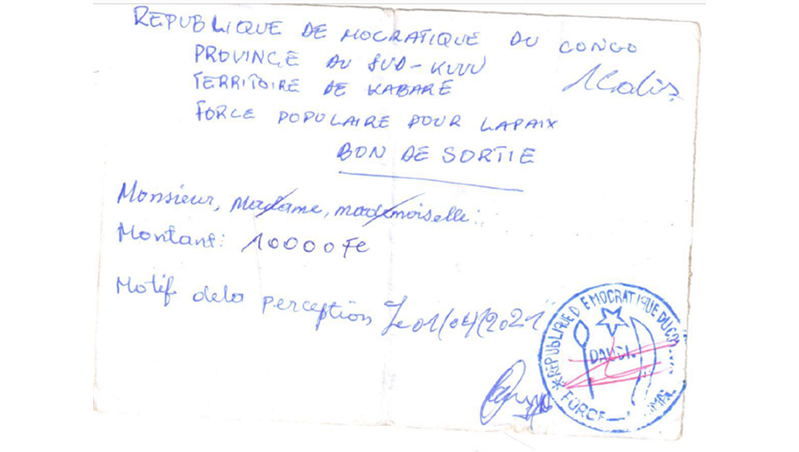

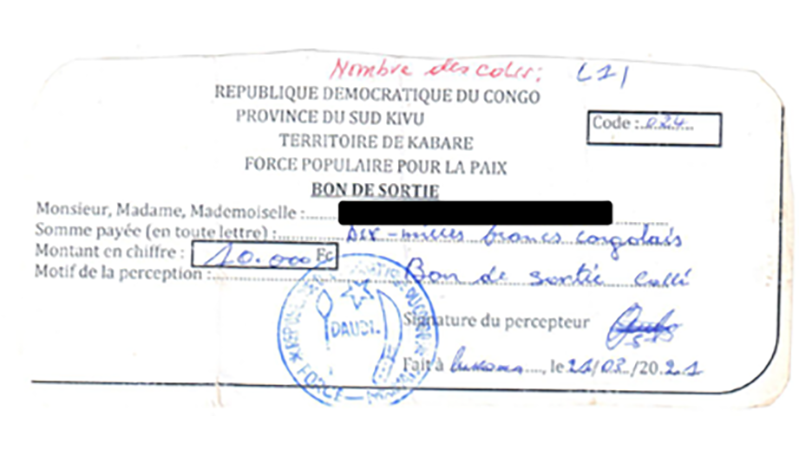

One of those mines was Lukoma, where a militia has used violence against the local population and forced miners to work unpaid, as well as exacting a levy from traders. The Ministry of Mines is said to tag bags despite being aware of this illegal levy.

Proofs of payment of illegal levies on transported minerals issued by an armed group at the Lukoma mine, 2021

Proof of payment of levies on transported minerals paid to an armed group at Lukoma mine, 2021

ITSCI has been aware of the risk of conflict minerals contaminating its supply chain around Nzibira since at least 2014, when its own governance assessment acknowledged the danger.

A 2015 report by a local NGO presented evidence of large volumes of tagged minerals being falsely attributed to unproductive validated mines in the area.

These findings were corroborated by a consultant commissioned by the US NGO Pact, ITSCI’s implementing partner, who also confirmed that tagged minerals came from areas controlled by militias. The consultant concluded that government officials and local ITSCI agents were aware of the situation and were engaged in a cover-up.

While ITSCI acknowledged allegations of laundering, it omitted from its public incident reporting mention of the most problematic issues identified by its own consultant, namely militia involvement and its own agents’ complicity.

ITSCI apparently failed to tackle the alleged problems, as a 2018 UN report again found evidence of laundering of minerals from mines controlled by a militia and the Congolese army.

This investigation documents that in 2021 the same problems seem to persist.

The situation in Nzibira is far from unique. In nearby Lubuhu, around 15 times as much cassiterite (tin ore) was tagged in the first quarter of 2021 as was produced in the two validated mines in the vicinity.

One trader told Global Witness that he had declared minerals as coming from one of these mines despite it being common knowledge that it had been inactive for a year.

A government official at another tagging site told Global Witness that he did not need to know where minerals came from in order to tag them. Some minerals tagged here again originated from a mine controlled by a militia that forces miners to work.

Drawing on witness interviews and reports by the UN and others, we have identified similar suspected failures of the ITSCI scheme at another seven tagging centres in North and South Kivu, and we have learned of at least 10 other mines controlled by armed groups where it appears that minerals are being or have recently been laundered into the system.

Tainted minerals entering the ITSCI scheme in DRC

ITSCI’s minimal field staff and lack of oversight make it easy for miners and traders to launder minerals.

Sources further allege that, without authorisation, ITSCI field staff actively collaborate with miners and officials to launder minerals and in some cases take a cut of the illicit proceeds. Government agents, who are typically paid poorly, aim to tag as many bags of minerals as possible, regardless of their origin.

This is considered a matter of national pride and a response to the rampant smuggling of minerals from DRC to Rwanda. Rwanda has for a long time profited from smuggled minerals from DRC, as UN and NGO reports have continually documented.

Forced labour at Biholo mine, DRC

The sheer volume of illicitly tagged minerals and the lack of effective action to address a known problem suggest that ITA, the body with ultimate oversight of ITSCI, ignores them.

Tagging high volumes of minerals is in ITA’s interest as the system is largely funded by levies paid by the exporters of tagged 3T minerals from the Great Lakes region, creating perverse incentives which undermine ITSCI’s control function.

Moreover, ITA finds itself in an obvious conflict of interest in running a system supposed to prevent tainted 3T minerals from entering international markets, while representing some of the largest 3T minerals buyers.

When approached for this report, ITA and Pact disagreed that the above-stated shares of minerals were illegitimately introduced into the ITSCI scheme in Nzibira or Lubuhu, and denied that ITSCI’s supply chains in Nzibira and Nindja are contaminated with minerals from mines linked to armed conflict and child labour.

ITSCI also disagreed that it has failed to monitor or take appropriate action with regard to the Nzibira supply chain. ITSCI denied any conflict of interest and denied any allegation of downplaying or ignoring incidents in its supply chains.

Pact denied that its agents are often aware of the laundering of minerals and stated that the organisation applied internal processes to identify cases of misconduct.

Mineral trafficking and outbursts of violence in Rubaya

Concerning evidence of ITSCI’s failings comes from the Rubaya area in North Kivu, which is estimated to account for at least 15% of the world’s coltan supply.

When the concession holder Société Minière de Bizunzu (SMB) decided to switch from ITSCI to a rival traceability scheme in December 2018, ITA allegedly issued its downstream members with alerts warning them about security and traceability issues with the company's concession in an apparent attempt to undermine both the company and the rival scheme.

This ultimately culminated in 120 tonnes of SMB-owned minerals being blocked. SMB had already been struggling financially, which often resulted in late payments to miners who consequently trafficked minerals to a neighbouring concession to be sold.

These actions exacerbated these pre-existing tensions between SMB and artisanal miners, who began to protest against late payment and to sell minerals from the concession to another company, Société Aurifère du Kivu et du Maniema (SAKIMA). The situation eventually erupted into violence in 2019 and 2020 leaving at least five dead.

ITSCI’s actions here may have undermined its own objective of breaking the link between minerals and conflict.

Violence in Rubaya, DRC

Minerals trafficked by miners from SMB’s concession to SAKIMA’s neighbouring concession are then illicitly introduced into the ITSCI supply chain, data published by the UN suggests.

ITSCI’s baseline mine production estimates, on which it relies to assess the output of taggable minerals, exceed mine production estimates from a UN source tenfold at some of SAKIMA’s mines, with the discrepancy likely to be accounted for by trafficked minerals.

Officials may have fraudulently introduced hundreds of tonnes of coltan from the SMB concession into ITSCI supply chains in 2020 alone. The shift of coltan volumes in favour of SAKIMA should have been unmistakable given its massive scale.

Minerals laundered via SAKIMA and tagged by ITSCI would subsequently be exported by two ITSCI member companies, which have become the leading coltan exporters in North Kivu – Coopérative des Artisanaux Miniers du Congo (CDMC) and Société Générale de Commerce SARL (SOGECOM), evidence suggests.

Global Witness has identified CDMC’s chairman to be British businessman and former TIC president John Crawley.

A 2020 meeting at the Congolese Ministry of Mines showing Crawley as chairman of CDMC (“PCA CDMC”)

ITSCI stated that it has “no reason to consider” that its baseline mine production data is inaccurate and rejected any allegation of having abused the ITSCI incident system or of having contributed to the outbreak of violence in the Rubaya area.

Crawley and CDMC denied that he is chairman of, or has any connection to CDMC.

CDMC added that it has never been informed of or shown any evidence of cross-concession mineral fraud at Rubaya.

SOGECOM denied purchasing coltan directly from SAKIMA in 2019 and 2020.

SAKIMA did not respond to our invitation to comment.

Rwanda

In Rwanda, where ITSCI’s scheme was first widely-used, the introduction of huge quantities of minerals smuggled from DRC was present from the outset.

The possibility of tagging tainted minerals in Rwanda, which has only a small mining sector, and exporting them as if they were legitimate appears to have incentivised mineral smuggling from DRC to Rwanda.

A key person involved in setting up the ITSCI scheme in Rwanda estimated that for some years only about 10% of the minerals the country exported were actually extracted there, with the rest being smuggled from DRC.

Attempted smuggling of coltan from North Kivu to Rwanda in 2017. UNGoE

The Rwandan government is fully aware that the country’s production figures are inflated by smuggling, multiple industry sources told Global Witness. Neither the government nor the ITSCI programme publishes the sort of mine-level production data which might be able to prove otherwise.

While ITSCI has taken action against some minor incidents of mineral smuggling, large companies that have exported the bulk of the smuggled minerals were reportedly left alone.

The most important of these companies was Minerals Supply Africa (MSA), for some years the largest exporter of 3T minerals from Rwanda. One source estimates that between 2011 and 2017 only a tiny share of its exports from Rwanda was actually mined there.

Swiss businessman Chris Huber (currently under criminal investigation for war crimes in DRC) has also allegedly profited from using the ITSCI scheme to launder smuggled minerals through at least three companies.

Smuggling from DRC to Rwanda has decreased since around 2014, at which time the ITSCI programme began to expand its presence in DRC. Nevertheless, smuggling of 3T minerals has continued to pay much better than mining.

A rare glimpse of Chris Huber

Some industry sources have even suggested that the laundering of smuggled minerals was the very reason why ITSCI was set up.

They have alleged that the CEO of MSA collaborated with ITA and Rwanda’s then Defence Minister to establish a government-backed traceability scheme that he envisaged would counter the risk posed to this illegal trade by stricter regulation in end-user countries.

ITSCI strongly rejected the claim that the ITSCI programme facilitates the laundering of high volumes of smuggled minerals in Rwanda and denied any allegation of wilful wrongdoing or collusion.

The Rwandan Mines, Petroleum and Gas Board states that it is fully compliant with OECD and ICGLR guidelines.

Chris Huber denies any ties to companies involved in alleged smuggling and these companies deny having exported smuggled minerals from Rwanda.

MSA denied that it has laundered smuggled minerals through the ITSCI system.

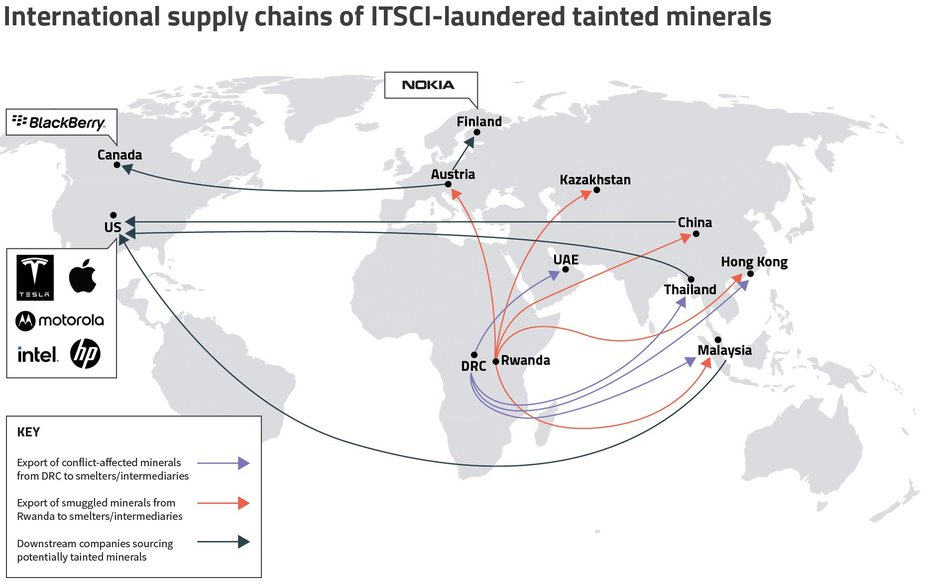

International supply chains

Tracing supply chains, we have identified companies that have likely sourced smuggled and/or conflict minerals, including smelters and intermediaries in Hong Kong, Dubai, Thailand, Kazakhstan, Austria, Malaysia and China (see map).

We have found these minerals may end up in products by international brands such as Apple, Intel, Samsung, Nokia, Motorola and Tesla.

Global Witness

Many international companies sourcing 3T minerals for their products, including for computers, electronics and cars, arguably do too little to detect smuggling, fraud, conflict links and child labour in the supply chain.

Instead of investing proper resources to identify, address and be transparent about such issues in their supply chains, many smelters rely heavily on ITSCI.

Similarly, downstream companies often rely heavily on an industry programme run by the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), which in turn relies on ITSCI, despite the scheme’s apparent systemic flaws.

Our findings suggest that two major smelters that have likely sourced conflict minerals are certified as conforming to the RMI standard.

A display of iPhone 13 smartphones containing tantalum in the Apple Inc store in London, 2021. Chris Ratcliffe / Bloomberg via Getty Images

Apple and Intel have reportedly monitored their Rwanda supply chains since around 2011 and have been warned about the high risk of sourcing smuggled minerals, but have seemingly applied few meaningful mitigation measures.

Neither company has publicly acknowledged the risk of buying minerals smuggled from DRC, according to our research. Other companies have knowingly sourced smuggled minerals from Rwanda, industry sources told Global Witness.

In response to questions from Global Witness, Apple, Intel, Nokia and Samsung all reiterated their commitment to responsible sourcing and referred us to respective policies, reports and initiatives in which they participate.

Motorola and Tesla did not respond to our request for comment.

Key recommendations

International Tin Association and Tantalum-Niobium International Study Center

- Reform the governance structure of the ITSCI system to avoid conflicts of interest between its members and the traceability and due diligence functions of the system.

- Publish detailed mine-level production data for minerals tagged by ITSCI along with other information that ITSCI has promised to make public.

Government of the Democratic Republic of Congo

- Conduct a thorough, independent assessment of the implementation of the ITSCI scheme and depending on the findings of this, consider revoking the scheme’s permission to operate and consider the options for replacing ITSCI with a scheme run by an independent institution.

- Improve links between, on the one hand, due diligence and traceability processes and, on the other hand, formalisation of artisanal mines and local sustainable economic development, in order to create incentives for upstream stakeholders to support responsible supply chains.

- Strengthen efforts to disarm, demobilise and reintegrate members of non-state armed groups.

Government of Rwanda

- Enforce measures to intercept smuggled minerals entering the country and to repatriate them to the country of origin.

- Publish key data for each mine, including production data, number of miners, location and the holder of the mining title.

3T exporters in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda

- Conduct supply chain due diligence in line with the OECD Due Diligence Guidance, including identifying and mitigating risks, and reporting in detail, as legally required, on the risks encountered and the steps taken to mitigate these risks on an annual basis.

Responsible Minerals Initiative

- Reduce reliance on ITSCI and other upstream assurance mechanisms by requiring smelters to conduct their own due diligence beyond reviewing data from upstream assurance mechanisms.

US government

- Enforce section 1502 of the Dodd–Frank Act with respect to companies sourcing minerals from the African Great Lakes region.

European Commission

- Fully scrutinise and hold accountable audited companies and companies that are members of recognised industry schemes, to ensure that they meet the full requirements of the Minerals Regulation and do not rely solely on the membership of a scheme or an audit to meet the relevant obligations.

Countries without due diligence legislation for minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas:

- Put in place legislation mandating responsible supply chain due diligence in line with OECD Due Diligence Guidance requirements and sanction companies not adhering to this.

Downstream companies

- Conduct their own due diligence and avoid as far as possible reliance on assurances from industry schemes.

Resource Library

The ITSCI Laundromat

Download Resource