It’s a reality check time for COFCO and its financiers. COFCO - China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation - is China's largest agricultural processing and trading company, and one of the world's largest agribusiness traders. The production of soy and palm oil, commodities traded by COFCO, is a key driver behind the destruction of the world's most biodiverse and climate-critical forests.

A poster child for global banks seeking to make 'green' investments, in June 2023, COFCO was alleged by Repórter Brasil and the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network to have been buying soy and palm oil grown on deforested land in Brazil and Indonesia.

Their investigation also highlighted that COFCO has been purchasing from deforesters in Brazil and Indonesia whist being granted billions of US dollars-worth of ‘green’ loans with lower interest designed to help the company clean up its supply chains.

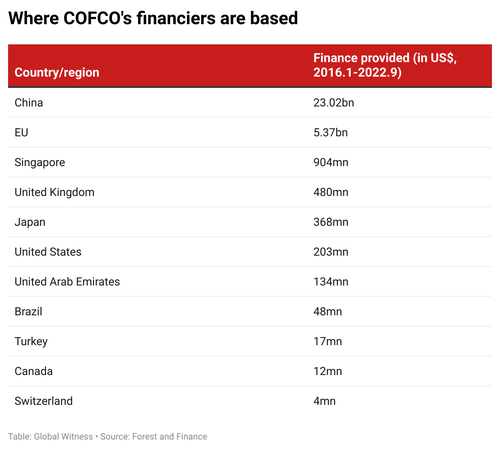

Now, new Global Witness analysis has found that major banks and investors around the world, led by those in China and the EU, have provided COFCO with more than $31.4bn from January 2016, right after the Paris Agreement was adopted, to September 2022. COFCO allegedly continued to source from farms with deforestation during this time, despite making sustainability pledges. Our analysis was based on data published by the Forests and Finance database.

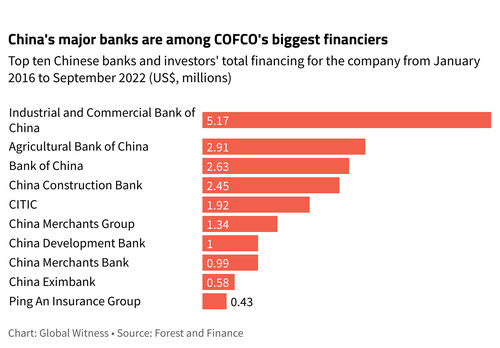

Banks and investors headquartered in China are by far the largest financiers for COFCO, accounting for more than 73% of the total financing the company received over the period, providing over $23 billion.

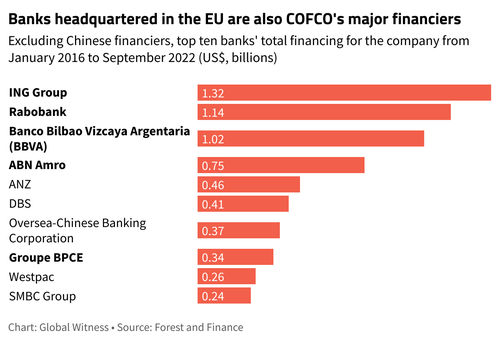

The EU emerged as the second largest source of financing for COFCO, with banks based in the Netherlands and Spain accounting for most of the region’s financing. The EU’s financing over the period accounted for nearly 17% of the total financing COFCO received – over $5 billion.

The EU has adopted a new law to limit its deforestation and forest degradation footprint abroad by restricting the importation of commodities like soy and palm oil grown on deforested land after a 31st of December 2020 cut-off date. However, this analysis demonstrates that there is an urgent need for the EU to also move quickly to regulate its financial sector to prevent investment in forest destruction.

Global Witness’ analysis also shows that in total, from 2019 to 2022, $4.6bn worth of so-called ‘sustainability linked loans’ were provided to COFCO International, an international trading arm of COFCO.

Such loans not only implied COFCO's green credentials but also allowed COFCO to pay less interest if it met pre-set sustainability-linked targets. COFCO claimed it met all targets set up in the first of its ‘sustainability-linked loans’ - which were at the time the largest received by a commodity trader - and unlocked lower interest. A spokesperson for BBVA, one of the leading lenders, said they were 'impressed by COFCO International’s journey and ability to outperform its targets’.

While details of such targets are guarded as ‘confidential’ and not published, COFCO International's statements and media reports suggest they are related to increasing traceability and better screening of its suppliers, especially related to its sourcing of soy in Brazil.

The new Repórter Brasil investigation challenges whether COFCO has done enough to ensure its soy and palm oil supply chains are indeed deforestation free. Its case studies exposed flaws in COFCO’s approach, which include a lack of proactive due diligence systems, weak oversight of indirect suppliers, and a failure to spell out its own obligations in the case of noncompliance.

Repórter Brasil is not the first to raise alarms on COFCO, and its investigation adds further weight to a growing body of evidence that raises questions about the company, which made pledges to eliminate deforestation from its supply chains for soy, beef and palm oil by 2025 during last year’s climate summit COP27.

Fifteen of COFCO's soy suppliers were found to have been fined or embargoed for recent violations of state or federal rules in just one state in Brazil, the world's largest producer of soybeans. PHOTO: PATRICIA MONTEIRO/BLOOMBERG VIA GETTY IMAGES

Soy: COFCO’s links to deforesters

COFCO International is a major exporter of soybeans from Brazil, the world's largest producing country of this highly sought-after commodity. In 2020, the company was the fifth largest soybean exporter from Brazil, shipping 5.7 million tonnes of soy from the country, according to data platform Trase. Much of this soy originates from the threatened Brazilian landscapes of the Cerrado and Amazon.

The Repórter Brasil investigation focused on one major soy producing province in Brazil - Mato Grosso, where reportedly mostly illegal expansion on soy farms replaced more than 500,000 hectares (close to the size of Shanghai) of natural vegetation from 2008 to 2019. Repórter Brasil found that 15 of COFCO’s suppliers “had been fined or embargoed for recent violations of state or federal rules. At least five and as many as 11 of those 15 suppliers were under an active embargo during the time COFCO did business with them”.

The investigation took a closer look at two of these suppliers with a history of deforestation. In the Cerrado, Repórter Brasil found that COFCO bought soy from a supplier under an active embargo for illegal deforestation – the ban was a result of forest clearance beyond the farm’s boundary. In addition, the supplier continued to grow soy within the embargoed area through the time of its sales to COFCO, a violation of COFCO’s requirements for suppliers.

In the Amazon, Repórter Brasil found that COFCO was a key client for a soy farmer whose operation violated the Soy Moratorium - an agreement among soy traders barring them from buying soy grown on deforested land in the Amazon region. Because of the Moratorium, the farmer said his crops were rejected by other clients. However, COFCO, a signatory of the Moratorium, kept buying from this farm. This seems to be a clear violation of COFO’s own policy which requires suppliers to respect the Moratorium.

COFCO insisted that neither case showed a violation of its commitments because the soy it bought came from a different section of the farm registered separately from the areas under embargo or covered by the Moratorium.

But the journalists pointed out that the different sections are in fact connected - and soy may be stored together as sections shared a grain silo in one case. When asked what they have done to monitor and ensure compliance of suppliers, COFCO said it takes numerous measures to monitor and enforce its supply chain standards - but noted that these farmers are indirect suppliers and they are “working to increase traceability of indirect purchases, which will lead us to strengthen our controls and risk monitoring for this part of the supply chain”.

Others have also raised concerns about the company's soy supply chains before. Mighty Earth, an environmental NGO, has alleged that there has been 21,498 hectares of forest clearance in Brazil by suppliers linked to COFCO since October 2017, most of which it described as "possibly illegal" due to the possibility it has taken place in legal reserves and preservation areas. COFCO has denied sourcing from some of the farms identified by Mighty Earth, adding that the NGO's analysis does not conclusively identify specific farms where soy has been grown. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) reported in May 2021 that COFCO could have supply chain links to an Amazon farmer who was “fined and sanctioned multiple times after destroying swathes of the rainforest”. COFCO said their audits confirmed all suppliers were compliant with Moratorium requirements.

Journalists found that COFCO had bought palm oil fruit grown illegally inside Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve in Indonesia. The production of Palm oil, used widely in products from food to cosmetics, is one of the key drivers of deforestation. PHOTO: JANUAR/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Palm oil: COFCO’s links to deforesters

As COFCO doesn't produce its own palm oil, the only way to ensure this oil is not associated with deforestation or human rights abuses would be to monitor its suppliers and exclude those with environmental and social risks. COFCO International requires suppliers to avoid deforestation in its supplier code of conduct. But increasing evidence suggests that the company hasn't done enough to scrutinise its suppliers.

Repórter Brasil reported that in 2022, COFCO International bought palm oil fruit grown illegally inside Rawa Singkil Wildlife Reserve, known as “orangutan capital of the world”, in South Ache, Indonesia. The mill that supplied COFCO International with palm oil was already exposed three years ago for sourcing illegal palm oil from the same Reserve, which resulted in it being added onto Unilever's blacklist of suppliers. But the mill remained as COFCO International's supplier, according to the latest list of suppliers published in 2021. Repórter Brasil also found 10 mills that had been suspended or banned by Unilever were still among COFCO’s most recently listed suppliers, and at least three other mills have been linked to allegations of illegal deforestation or land grabbing.

COFCO said it was unaware of both cases of illegal deforestation in the Wildlife Reserve since the mill is an indirect supplier and one among the nearly 1,000 of its suppliers. And because of this, they said there was ‘no valid reason’ for them to engage with its direct suppliers who bought from this mill.

Repórter Brasil findings tally with what Global Witness has previously found. In 2021, our analysis revealed that 77 processing facilities that had been suspended by palm oil giant Unilever for non-compliance with its sourcing policies were still listed as COFCO suppliers in 2019. This is based on the latest disclosures from Unilever (September 2020) and COFCO (in 2019) then. It is concerning that COFCO has failed to exclude suppliers that have been in breach of Unilever's sourcing policy dating back as far as 2010, and therefore could be guilty of deforestation.

New financial regulations are necessary

As the world measurably edges closer to the 1.5°C limit in global average temperature rise, the global financial sector must take urgent action to reduce its impacts on forests.

It is not enough to rely on so-called green finance to incentivise companies to change – indeed this analysis shows green finance alone is not sufficient to ensure major commodity traders close loopholes in their supply chains. Clear and mandatory rules are needed for all financiers to prevent them from investing in forest destruction, whilst there are still forests left to save.

Major economies such as the EU and the UK recently passed legislation requiring companies to screen out deforestation in their supply chains, and the investment of billions of dollars in COFCO shows they must now extend that legislation to also prevent their financiers from profiting from deforestation. As the US considers its own impact on global deforestation, it should take similar action.

China too must take action. Global Witness' analysis in 2021 highlighted clear warning signs that Chinese financiers currently have inadequate safeguarding in place to address risks associated with deforestation. The Chinese government must ensure that national laws and major Chinese green finance policies address global deforestation. The Chinese banking regulator must go beyond asking the banks to report on the volume of the so-called ‘green’ lending to companies producing and trading certified agricultural commodities and instead require them - under the Green Finance Guidelines and via a revised law on commercial banks - to provide evidence to show how they are scrutinising and reducing lending to companies linked to global deforestation.