Sometime in the past decade, “nature-based solutions” (NBS) began to feature in both corporate and international policy discussions on climate change, usually alongside descriptions of efforts to either increase carbon storage, or limit greenhouse gas emissions.

Big polluters have spent decades denying climate change. Now, they’re using greenwashing and other tactics to promote false solutions to the climate crisis that distract and delay. We are challenging this and pushing for regulatory changes to hold them accountable by preventing companies from misleading the public about their environmental impact, and forcing them instead to take meaningful action to meet global climate goals.

Alert to these patterns of corporate greenwashing, we wanted to investigate

whether big polluters are using NBS to present false solutions to their

climate-damaging practices, helping them maintain their social license. In a joint digital methods project with King’s College London, PEBES, the Public Data Lab and Politecnico di Milano’s DensityDesign Lab, we set out to empirically explore the digital existence of NBS.

We wanted to answer the following questions: When did the notion of NBS first appear online? Who, corporate or otherwise, uses it the most? Has there been an evolution in who uses it, when they use it and where? And, importantly: what can we learn about the potential co-option of the term by looking at its origins and trajectory?

The online life of “nature-based solutions”

Drawing on digital methods – which is the use of online and digital technologies to collect and analyse research data – Public Data Lab, PEBES and DensityDesign Lab gathered online materials associated with NBS on a variety of online platforms and spaces: Twitter, YouTube, Google Search, and an academic abstract and citation database called Scopus. We presented the findings on DensityDesign Lab’s data visualisation and mapping tool PlacPlac, and explored the findings in joint workshop.

As it turns out, NBS is brought into play across a wide array of political and corporate contexts. NBS appears repeatedly in discussions of water infrastructure projects and urban development across the surveyed online spaces, but also in the contexts of Indigenous knowledge, food security, poverty eradication, pollination, farming, herbicide, reforestation, afforestation, and forest conservation. The precise understanding of the phrase seems to differ depending on both the field and setting. It is as easily used to describe large scale tree planting for carbon offsetting projects as it is to describe grassroots-driven restoration of damaged coastal ecosystems.

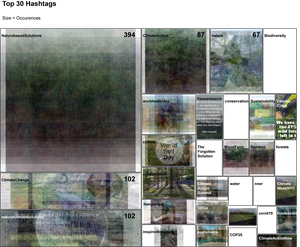

The treemap shows, as an overlay composite, the images used by the 30 tags with the highest presence. The dimension of each area corresponds to the number of times the tag has been used. Treemap done with RAWGraphs.

Despite this, in its decade and a half of circulation, NBS has not become a household term. Its usage appears to be largely confined to professional spaces, and seems to have grown primarily within a European policy bubble. A review of academic citations showed that European Union organisations constituted five of the top 20 funders of academic articles about NBS, with EU research and innovation funding programme Horizon 2020 topping the list. Over 1,610 publications mention NBS between 2012 and 2022, and the most referenced article focuses on NBS in the context of the European Union.

The phrase’s academic online lifespan has also been relatively short. The reviews of academic literature pinpointed the first online use of NBS in a 2008 World Bank report – only in its title – followed by a mention of it by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) the following year. In an analysis of 376,227 tweets and their respective metadata – which was extracted using data scraping and analysis tool 4cat – a timeline materialised, demonstrating the term’s first emergence on the platform, as well as its particular popularity in relation to disaster risk management efforts following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident.

In short, NBS is a broad and malleable concept. It can function as a catch-all phrase for environmental action – which, in turn, creates an opening for it to be deployed to obfuscate harmful corporate behaviour.

Convenient ambiguity: “nature-based solutions” seem difficult to define and easy to co-opt

There have been significant efforts to define NBS, as exemplified by the 2016 publication of the IUCN’s Global Standards for NBS. Despite such efforts, however, a consensus definition of the term continues to evade those who use it. It appears to be inherently contested across academic literature, which acknowledges the “lack of clarity” around the "poorly defined" and "vague" concept. One article explicitly states it does not intend to nail down a strict definition. What are these wildly disparate interpretations of NBS meant to communicate about the motivations behind the use of the term? And to what extent does its slippery definition stand in the way of effective policymaking?

It is not that definitions of nature-based solutions do not exist – many, many do – but this sustained lack of consensus allows for the clear displacement we observed of the term from its origins in biodiversity and disaster risk reduction to its more recent deployment in relation to efforts (of all kinds) to combat climate change. Increased vigilance over the misuse of NBS could help to address its adoption for more nefarious purposes.

Outside academic circles, the use of NBS also presents stark contrasts. International organisations refer it in biodiversity-related briefings, and big polluters make use of it in promotional materials to placate increasing public pressure to cut emissions. Ultimately, this can distract from companies’ continued destruction of the climate by creating a false sense of comfort. It is a relief to be offered a solution to an existential threat – regardless of who we are trusting to verify and implement it. If a solution implemented is “nature-based”, this soothingly implies that nature still has the power to heal itself in this late stage of the climate crisis. Maintaining the status quo appeases any discomfort felt when climate activists call for radical change and systemic overhaul.

“Old wine in new bottles”: familiar greenwashing tropes

In some cases, NBS present wholly false solutions that empower some of the most damaging corporate actors on the planet to carry on their business as usual. In a recent and particularly egregious example, Chevron announced a new carbon offsetting reforestation project in March, describing it as a “nature-based solution” that is “expected to remove carbon from the atmosphere”. Fifteen days after their announcement, Global Witness published its findings that Chevron plans to spend $67 billion on developing new oil and gas fields in the next seven years alone.

Messaging surrounding nature-based solutions still roundly acknowledges that changing company behaviour is necessary in the fight against climate change. A compelling visual story of brand co-option of NBS for greenwashing purposes emerged from our queries. In an analysis of Google Image search results, we observed a shift from photographs of mangroves, forests, mountains and animals to diagrams, reports, and other policy materials – which perhaps reflects a turn from the phrase’s initial promise to its institutionalisation and implementation.

An example of the results of our Google Image Search query.

What’s more, the narrative offered in most of the YouTube content from high-polluting companies is glaringly clear: by promoting NBS, they make it seem as if they were part of the economically realistic solution the world needs to combat climate change. These videos fail to mention who caused environmental destruction in the first place. They also evade mention of who profits from continued destruction. Instead, the videos tend to assign responsibility for such damage to a collective “we”.

In one promotional video from the oil and gas giant Shell, the script reads “Shell is harnessing nature” and “protecting forests under threat” against picturesque footage of woodland and renewable energy projects. Meanwhile, analysis by Urgewald and the Guardian places the company among the top four worldwide for “average annual investment in oil and gas exploration over the past three years”. This stasis does not bother all scientists, however: a TED Talk that surfaced in our YouTube research featured an ecologist touting NBS as a “climate solution” with broad appeal, “that can engage every single one of us”.

“Until now climate action has always been about giving up the things we love and while those commitments are incredibly important to cut GHG emissions we now also have positive actions which make us feel good and make us involved in the fight,” he said.

But it is important to note that Google Search results showed that many pages that mention NBS voiced concerns echoing ours – open letters, reports, and blog posts highlighted the ways in which the term displaces blame and obfuscates the path to meaningful change. However, these sources often did not feature in the most prominent materials associated with the term in query results on platforms such as Twitter and YouTube. Tweets critiquing NBS begin to emerge in 2012 alongside the steady promotion of nature-based solutions by the IUCN and other international organisations. In 2013, the tweets amplify and diversify, with corporations entering the debate, leading most notably to some tweets in 2019 quoting the role of NBS on the World Economic Forum in Davos in a partnership between Dow Chemical and the Nature Conservancy.

Collaborations on climate

A second workshop built on these research findings to explore their potential policy implications and identify pathways for continued collaboration. The findings from this collaboration with King’s College London, PEBES, the Public Data Lab and DensityDesign Lab provide an excellent base of information and tools to support Global Witness’ campaign against greenwashing and false climate solutions.

When "nature-based solutions" and other environmental labels are so loosely applied and invoked without explicit references or regard to definitions, principles or certification, there is a risk they will be co-opted to undermine efforts to combat climate change with the urgency and scale the world requires. This joint project has given us new perspectives on the circulation of terms and narratives which have been used to foster a sense of climate optimism and benevolent business, while sidestepping the critical action of drastic emissions cuts needed to limit global heating.

Project collaborators

- Ángeles Briones, Post-doc research fellow, DensityDesign Research Lab, Politecnico di Milano

- Anna Smith, PhD Candidate, King’s College London

- Arianne Griffith, Senior Campaigner, Corporate Accountability, Global Witness

- Beatrice Gobbo, DensityDesign Research Lab, Politecnico di Milano

- Henry Peck, Campaigner, Corporate Accountability, Global Witness

- Jonathan Gray, Department of Digital Humanities, King’s College London + Public Data Lab

- Kari De Pryck, Researcher, PACTE Université Grenoble Alpes

- Malina McLennan, Data Investigations Advisor, Global Witness

- Maud Borie, Political Ecology, Biodiversity & Ecosystem Services research group, Geography, King’s College London

- Sam Leon, Data Investigations Lead, Global Witness

- Thais Lobo, Research and Teaching Assistant, King’s College London

- Tommaso Venturini, Researcher, CNRS, Center for Internet and Society, Associate Professor, Université de Genève, Medialab

![VCMIsimple4[60].png](https://cdn2.globalwitness.org/media/images/VCMIsimple460.2e16d0ba.fill-544x300.png)